Regina Jonas

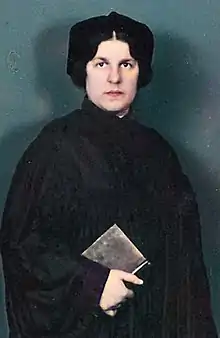

Regina Jonas (German: [ʀeˈɡiːna ˈjoːnas]; German: Regine Jonas;[1] 3 August 1902 – 12 October/12 December 1944) was a Berlin-born Reform rabbi.[2] In 1935, she became the first woman to be ordained as a rabbi.[2] Jonas was murdered in the Holocaust.[2]

Regina Jonas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Regine[1] Jonas 3 August 1902 |

| Died | 12 October or 12 December 1944 (aged 42) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Alma mater | Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, Berlin |

| Occupation | Reform rabbi |

| Signature |  |

| Semikhah | December 27, 1935 |

Early life

Regina Jonas was born into a "strictly religious" household in the Berlin Scheunenviertel, the second child of Wolf Jonas and Sara Hess. Wolf, who was probably Regina's first teacher, died when she was 13. Like many women at that time, she intended to make a career as a teacher. After graduating from the local Höhere Mädchenschule, she became disillusioned with the idea of becoming a teacher. Instead, she enrolled at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (Higher Institute for Jewish Studies), in the Academy for the Science of Judaism, and took seminary courses for liberal rabbis and educators for 12 semesters. While not the only woman attending the university, Regina sent ripples through the institution with her stated goal of becoming a rabbi.

To this end, Jonas wrote a thesis that would have been an ordination requirement. Her topic was "Can a Woman Be a Rabbi According to Halachic Sources?" Her conclusion, based on Biblical, Talmudic, and rabbinical sources, was that she should be ordained. The Talmud professor responsible for ordinations, Eduard Baneth, accepted Jonas' thesis; however, his sudden death squashed any hope Jonas may have had in receiving an official ordination. Jonas graduated in 1930, her diploma only naming her as an "Academic Teacher of Religion". Jonas then applied to Rabbi Leo Baeck, spiritual leader of German Jewry, who had taught her at the seminary. Baeck, while acknowledging Jonas as a "thinking and agile preacher", refused to make her title official, because the ordination of a female rabbi would have caused massive intra-Jewish communal problems with the Orthodox rabbinate in Germany.

For nearly five years, Jonas taught religious studies in a series of both public and Jewish schools, and also performed a series of 'unofficial' sermons. Her lectures on religious and historical topics for various Jewish institutions often included questions about the importance of women in Judaism. This eventually caught the attention of the liberal Rabbi Max Dienemann, who was the head of the Liberal Rabbis' Association in Offenbach am Main,[2] who decided to test Jonas on behalf of the association. Despite protest from both inside and outside the Liberal Rabbis' Association, on 27 December 1935, Regina Jonas received her semicha and was ordained.

Despite her ordination, Berlin's Jewish community was not welcoming. Archived files suggest she applied for employment at Berlin's New Synagogue, but was turned away. With Berlin's pulpits closed to her, Jonas sought work elsewhere. She found support in the Women's International Zionist Organization, which enabled her to work as a chaplain in various Jewish social institutions. In 1938, Jonas wrote a letter to Martin Buber, an Austrian Jewish philosopher, where she expressed some interest in emigrating to Palestine to possibly pursue potential rabbinical opportunities there.

Persecution and death

Because of Nazi persecution, many rabbis emigrated and many small communities were without rabbinical support. Jonas, possibly out of consideration for her elderly mother, stayed in Nazi Germany. The Reich Association of Jews in Germany allowed Jonas to travel to Prussia to continue her preaching; however, the Jewish situation under the Nazi regime quickly degraded. Even if there had been a synagogue willing to host her, the duress of Nazi persecution made it impossible for Jonas to hold services in a proper house of worship. Despite this, she continued her rabbinical work, as well as teaching and holding impromptu services.

On 4 November 1942, Regina Jonas had to fill out a declaration form that listed her property, including her books. Two days later, all her property was confiscated "for the benefit of the German Reich." The next day, the Gestapo arrested her and she was deported to Theresienstadt. While interned, she continued her work as a rabbi, and Viktor Frankl, who later became a renowned psychologist, asked for her help in building a crisis intervention service to prevent suicide attempts in the camp. Her particular job was to meet the trains at the station and screen disoriented newcomers arriving at the increasingly overcrowded ghetto with a questionnaire on the topic of suicide, designed by Frankl.[3][4]

Regina Jonas worked in the Theresienstadt camp for two years. Records of some 23 sermons written by Jonas survive, including What Is Power Nowdays - Jewish Religion, the Power Source for Our Ego Ethics and Religion.[5] During her two-year internment, Jonas was also a member of a group that organized concerts, lectures and other performances to distract others from events around them.[6]

Upon passing the June 1944 inspection, a number of summer months would pass at relative ease, until almost all of the Jewish Council, including Jonas, were then deported amongst the majority of the town, to Auschwitz in mid-October 1944, where she was murdered either less than a day[7][8] or two months[9][10] later. She was 42 years old.

Of the 520 or so who lectured in Theresienstadt, including Frankl and Leo Baeck[11] no one ever mentioned her name or work.[12]

Rediscovery

From Jonas' death until 1972 there is at least one brief mention in the Jewish press of her status as rabbi. In 1967, The Australian Jewish News reported on a conference of Liberal Judaism and their discussions of equality for women. The paper reported that a Rabbi Sanger of Berlin spoke of Regina Jonas as an ordained rabbi.[13]

Following the ordination of Rabbi Sally Priesand in 1972, The American Israelite reported in July 1973 that the only other known Jewish woman to receive ordination was Regina Jonas of Berlin. Also mentioned was that Jonas' thesis was titled "Can a Woman Become a Rabbi?"[14]

Pnina Navè Levinson, a student of Jonas, mentions her story in a 1981 paper[15] and subsequently, in a 1986 paper, Levinson notes that Jonas' story was never mentioned by notable individuals who were in Theresienstadt at the same time as Jonas.[16] Regina Jonas is also discussed briefly in a 1984 paper by Robert Gordis who notes Jonas was an early example of the ordination of a woman as rabbi.[17]

Regina Jonas's literary work was rediscovered in 1991 by Dr. Katharina von Kellenbach, a researcher and lecturer in the department of philosophy and theology at St. Mary's College of Maryland, who had been born in Germany.[18] In 1991 she traveled to Germany to research material for a paper on the attitude of the religious establishment (Protestant and Jewish) to women seeking ordination in 1930s Germany.[18] She found an envelope containing the only two existing photos of Regina Jonas, as well as Jonas' rabbinical diploma, teaching certificate, seminary dissertation and other personal documents, in an archive in East Berlin. It was newly available because of the fall of the Soviet Union and the opening of eastern Germany and other archives.[18][19] It is largely due to von Kellenbach's discovery that Regina Jonas is now widely known.[19]

In 1999, Elisa Klapheck published a biography about Regina Jonas and a detailed edition of her thesis, Can Women Serve as Rabbis?.[2][20] The biography, translated into English in 2004 under the title Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas – The Story of the First Woman Rabbi, gives voice to witnesses who knew or met Regina Jonas personally as rabbi in Berlin or Theresienstadt. Klapheck also described Jonas' love relationship with Rabbi Josef Norden.

Legacy

Though there had been some women before Jonas who made significant contributions to Jewish thought, such as the Maiden of Ludmir, Asenath Barzani, and Lily Montagu, who acted in similar roles without being ordained, Jonas remains the first woman in Jewish history to have become a rabbi.

A hand-written list of 24 of her lectures entitled "Lectures of the One and Only Woman Rabbi, Regina Jonas", still exists in the archives of Theresienstadt. Five lectures were about the history of Jewish women, five dealt with Talmudic topics, two dealt with biblical themes, three with pastoral issues, and nine offered general introductions to Jewish beliefs, ethics, and the festivals.

A large portrait of Regina Jonas was installed on a kiosk that tells her story; it was placed in Hackescher Market in Berlin, as part of a citywide exhibition titled "Diversity Destroyed: Berlin 1933–1938–1945," to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the National Socialists' rise to power in 1933 and the 75th anniversary of the November pogrom, or Kristallnacht, in 1938.[21]

In 1995, Bea Wyler, who had studied at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York, became the first female rabbi to serve in postwar Germany, in the city of Oldenburg.[22]

In 2001, during a conference of Bet Debora (European women rabbis, cantors and rabbinic scholars) in Berlin, a memorial plaque was revealed at Jonas' former living place in Krausnickstraße 6 in Berlin-Mitte.

In 2003 and 2004, Gesa Ederberg and Elisa Klapheck were ordained in Israel and the US, later leading egalitarian congregations in Berlin and Frankfurt. Klapheck is the author of Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas – The Story of the First Woman Rabbi (2004).

In 2010, Alina Treiger, who studied at the Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam, became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Germany since Regina Jonas.[23]

In 2011, Antje Deusel became the first German-born woman to be ordained as a rabbi in Germany since the Nazi era.[24] She was ordained by Abraham Geiger College.[24]

2013 saw the premiere of the documentary Regina,[25] a British, Hungarian, and German co-production[26] directed by Diana Groo.[27] The film concerns Jonas's struggle to be ordained and her romance with Hamburg rabbi Josef Norden.[28]

On 5 April 2014, an original chamber opera, also titled "Regina" and written by composer Elisha Denburg and librettist Maya Rabinovitch, premiered[29] in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was commissioned and performed by the independent company Essential Opera and featured soprano Erin Bardua in the role of Regina, and soprano Maureen Batt as the student who uncovers her forgotten legacy in the archives of East Berlin in 1991. The opera is scored for five voices, clarinet, violin, accordion, and piano.[30]

On 17 October 2014, which was Shabbat Bereishit, communities across America commemorated Regina Jonas's yahrzeit (anniversary of death).[31]

In 2014, a memorial plaque to Regina Jonas was unveiled at the former Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic, where she had been deported to and worked in for two years.[32][33] There is a short documentary about the trip on which this plaque was unveiled, titled In the Footsteps of Regina Jonas.[34][35]

In 2015, Abraham Geiger College and the School of Jewish Theology at the University of Potsdam marked the 80th anniversary of Regina Jonas's ordination with an international conference, titled "The Role of Women's Leadership in Faith Communities."[36]

In 2017, Nitzan Stein Kokin, who was German, became the first person to graduate from Zecharias Frankel College in Germany, which also made her the first Conservative rabbi to be ordained in Germany since before World War II.[37][38]

In August 2022, The New York Times featured Jonas in their obituary feature Overlooked.[39]

See also

References

- As documented by Landesarchiv Berlin; Berlin, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Geburtsregister; Laufendenummer 892 which reads:

"In front of the signed registrar appeared today... Wolff Jonas... and... Sara Jonas née Hess... on the 3rd day of August in the year 1902... a girl was born and (that) the child was given the first name Regine..."

The full document can be found here. - Klapheck, Elisa. "Regina Jonas 1902–1944". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Haddon Klingberg (16 October 2001). When life calls out to us: the love and lifework of Viktor and Elly Frankl. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50036-4.

- Kwiet, Konrad (1984). "The Ultimate Refuge: Suicide in the Jewish Community under the Nazis". Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook. 29 (1): 135–167. doi:10.1093/leobaeck/29.1.135. PMID 12879513.

- ""University over the Abyss" Elena Makarova, Sergei Makarov & Victor Kuperman".

- "Rabbi Regina Jonas". August 7, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07.

- "Regina Jonas | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- eJP (2015-10-08). "The First Woman Rabbi: Bringing Fraulein Rabbiner Regina Jonas into our Past and our Future". Ejewishphilanthropy.com. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- "Regina Jonas". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Jüdische Nachrichten. "Jewish Women in Berlin: Regina Jonas – The First Women Rabbi". Hagalil.com. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- "List of Lecturers in Ghetto Theresienstadt". University over the Abyss. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Klapheck, Elisa. Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas: The Story of the First Woman Rabbi, introductory chapter: "My Journey toward Regina Jonas"

- The Australian Jewish News (Melbourne), 24 November 1967

- "Newlyweds". The American Israelite. 19 July 1973. p. 19.

- Nave-Levinson, Pnina. "Women and Judaism." European Judaism 15, no. 2 (1981): 25.

- Levinson, Pnina Nave. "Die Ordination von Frauen als Rabbiner." Zeitschrift für Religions und Geistesgeschichte 38, no. 4 (1986): 289–310.

- Gordis, Robert. "The Ordination of Women – a History of the Question." Judaism 33, no. 1 (1984): 6.

- Vidalon, Dominique (2004-05-25). "A Forgotten Myth". Haaretz. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- "Commentary: Obscure no more, world's first woman rabbi receives recognition". The Washington Post. 2014-07-25. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- Elisa Klapheck (2004). Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas: The Story of the First Woman Rabbi. Translated by Toby Axelrod. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-7879-6987-7.

- "Walking in the Footsteps of Regina Jonas". Jwa.org. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- "Oldenburg". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Breitenbach, Dagmar (4 November 2010). "German Jews ordain first female rabbi since World War II". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- "Germany's first female German-born rabbi since the Nazi era". Cjnews.com. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "Filmpremiere: Reginia – Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Time Prints Regina". Timeprints.de. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "Regina". UK Jewish Film. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- "Rachel Weisz's father makes his movie debut". Thejc.com. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "New Works". Essentialopera.com. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "Regina A chamber opera in one act for five voices, violin, clarinet, accordion, and piano". Canadian Music Centre Library. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Top Ten Moments For Jewish Women In 2014". Jwa.org. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Sinai, Allon (25 July 2014). "First female rabbi, Regina Jonas, commemorated at Terezin site". Jpost.com. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Jüdische Nachrichten. "Jewish Women in Berlin: Regina Jonas – The First Women Rabbi". Hagalil.com. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "Short Film: In the Footsteps of Regina Jonas". Jwa.org. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Regina Jonas Remembered". Jwa.org. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Abraham Geiger Kolleg: Women in the rabbinate". Abraham-geiger-kolleg.de. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Leslee Komaiko (2017-05-24). "One L.A. school: two German rabbis – Jewish Journal". Jewishjournal.com. Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- Ryan Torok (22 June 2017). "Moving & Shaking: Wise School, "Jerusalem of Gold," and Gene Simmons – Jewish Journal". Jewishjournal.com. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Popkin, Gabriel (August 19, 2022). "Overlooked No More: Regina Jonas, Upon Whose Shoulders 'All Female Rabbis Stand'". The New York Times.

Sources

- Boulouque, Clémence. Nuit ouverte. ed. Flammarion, Paris 2007. Novel. (See Review by Claudio Magris "Una Donna per rabbino" Corriere della Sera, 2007)

- Geller, Laura. "Rediscovering Regina Jonas: The First Woman Rabbi", in The Sacred Calling: Four Decades of Women in the Rabbinate, Rebecca Einstein Schorr and Alysa Mendelson Graf, eds., CCAR Press, 2016; ISBN 978-0-88123-217-2

- Klapheck, Elisa. Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas: The Story of the First Woman Rabbi, Toby Axelrod (Translated) ISBN 0-7879-6987-7

- Makarova, Elena, Sergei Makarov & Victor Kuperman. University Over The Abyss. The story behind 520 lecturers and 2,430 lectures in KZ Theresienstadt 1942–1944. Second edition, April 2004, Verba Publishers Ltd. Jerusalem, Israel, 2004; ISBN 965-424-049-1 (Preface: Prof. Yehuda Bauer)

- Milano, Maria Teresa."Regina Jonas.Vita di una rabbina Berlino 1902 Auschwitz 1944" ed. EFFATA' 2012

- Sarah, Elizabeth. "Rabbiner Regina Jonas 1902–1944: Missing Link in a Broken Chain" in Sheridan, Sybil (ed.): Hear our Voice: Women in the British rabbinate, Studies in Comparative Religion series. Paperback, 1st North American edition. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1998; ISBN 1-57003-088-X

- Sasso, Eisenberg Sandy. Regina Persisted: An Untold Story, illustrated by Margeaux Lucas, Apples & Honey Press, 2018; ISBN 1-68115-540-0

- Silverman, Emily Leah. Edith Stein and Regina Jonas: Religious Visionaries in the Time of the Death Camps, Routledge, 2014; ISBN 978-1-84465-719-3

- Von Kellenbach, Katharina. "Denial and Defiance in the Work of Rabbi Regina Jonas" in In God's Name: Genocide and Religion in the 20th Century (Chapter 11), Phyllis Mack and Omar Bartov, eds., Berghahn Books, New York, 2001; ISBN 978-1-57181-302-2

- Von Kellenbach, Katharina. "'God Does Not Oppress Any Human Being': The Life and Thought of Rabbi Regina Jonas", The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book, Vol. 39, Issue 1, January 1994, pp. 213–225, doi:10.1093/leobaeck/39.1.213

External links

- A Case of Communal Amnesia, by Rabbi Dr. Sybil Sheridan, published May 16, 1999

- A forgotten myth, by Aryeh Dayan, Haaretz, published May 25, 2004

- In the Footsteps of Rabbi Regina Jonas, by Dr. Gary P. Zola, then Executive Director of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives and Professor of the American Jewish Experience at Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion, published August 27, 2014

- Regina Jonas: Audio feature from The Open University

- Regina Jonas: A Symbol of Female Empowerment in Jewish Life, by Liora Alban of Women of the Wall, published July 22, 2013

- Regina Jonas: "The one and only woman rabbi" during dark times, by Rabbi Elizabeth Tikvah Sarah, August 3, 2002

- Remembering Rabbi Regina Jonas, by Rabbi Sally Priesand, published 2014

- St. Mary's college of Maryland: Rabbi Regina Jonas Memorial page.

- Regina Jonas Remembered at the Jewish Women's Archive website.

- The First Woman Rabbi in the World

- Theresienstadt Ghetto

- "We Who Are Her Successors": Honoring Rabbi Regina Jonas, by Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, published 2014

- "Without Regard to Gender" A Halachic Treatise by the First Woman Rabbi, by Laura Major, published the summer of 2010