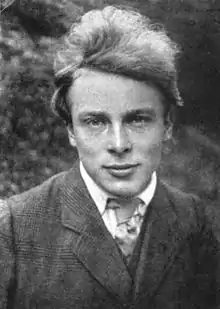

Reinhard Sorge

Reinhard Johannes Sorge (29 January 1892 – 20 July 1916) was a German dramatist and poet. He is best known for writing the Expressionist play The Beggar (Der Bettler), which won the Kleist Prize in 1912 and almost singlehandedly created surrealist theatre and modern theatrical stagecraft. After being subsequently received into the Roman Catholic Church, Sorge began an effort to bring the Catholic literary revival into the literature of the Germanosphere. Instead, Sorge was conscripted into the Imperial German Army in World War I in 1915. He was killed in action during the Battle of the Somme in the summer of 1916. Sorge's Der Bettler, however, received a posthumous premiere in a groundbreaking production by legendary Austrian Jewish stage director Max Reinhardt in 1918.

Reinhard Johannes Sorge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 January 1892 Berlin, Germany |

| Died | 20 July 1916 (aged 24) Ablaincourt, France |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | German |

| Literary movement | Expressionism |

Early life

Sorge was born in Berlin-Rixdorf, into the family of a middle class salesman of Huguenot descent. According to Tim Cross, the blight of Sorge's childhood was his father's mental illness. To escape this atmosphere at home, Sorge was sent to East Prussia to live with a Lutheran pastor and his family. There he recovered an inner balance, a sense of Christian purpose, and the foundation for his future development.[1]

When he was nine years old, Sorge's father died and his family moved to Jena. There, Sorge befriended the poet Richard Dehmel and, "absorbed the neo-romantic influences of the day."[2] He was also inspired by the writings of Stefan George and August Strindberg.

Sorge began to write at the age of sixteen, but lost his faith in Christianity after reading Also Sprach Zarathrustra by Friedrich Nietzsche. According to Rev. B. O'Brien, "The result was that he soon launched an attack on all that he conceived as a check on himself and his comrades. He caused common prayers and grace at table to be given up in his pious Lutheran home, and destroyed his young brother's belief in God and Heaven. In order to be free from the restrictions of school life, he left school a year before the end, with the resolution of studying for the leaving examination privately -- which he never did."[3]

Writing career

After leaving school, Sorge switched to writing full-time. According to O'Brien, "His first poem was called, 'The Youth,' and described his own Nietzschean ideals. The second was a complete play called, 'The Beggar: A Theatrical Mission,' which was again a drama about himself, a describes in a series of violent scenes how he tests and rejects various classes of men as unfit for the highest ideals."[4]

The Beggar was written during the last three months of 1911.[5]

According to Michael Paterson, "The play opens with an ingenious inversion: the Poet and Friend converse in front of a closed curtain, behind which voices can be heard. It appears that we, the audience, are backstage and the voices are those of the imagined audience out front. It is a simple, but disorienting trick of stagecraft, whose imaginative spatial reversal is self-consciously theatrical. So the audience is alerted to the fact that they are about to see a play and not a 'slice of life.'"[6]

According to Walter H. Sokel, "The lighting apparatus behaves like the mind. It drowns in darkness what it wishes to forget and bathes in light what it wishes to recall. Thus the entire stage becomes a universe of [the] mind, and the individual scenes are not replicas of three-densional physical reality, but visualizes stages of thought."[7][8]

While he awaited its publication, Sorge first visited Denmark and then stayed at the North Sea resort of Norderney, where he had a mystical experience that changed both his beliefs and the course of his entire life.[9]

According to his fiancee Susanne, Sorge attempted at Norderney to fulfill the doctrines of Nietzsche, who had argued that every pupil must surpass his teacher. Sorge struggled, amid the constantly overcast skies, to bring a new insight to mankind solely out of himself. Instead, Sorge drove himself on the edge of a mental breakdown and chose instead to accept the existence of the Christian God.[10]

In 1912, "The Beggar" was published to rapt reviews and subsequently awarded that year's Kleist Prize due to the influence of Richard Dehmel.

Sorge used his winnings to marry his fiancée, Susanne Maria Handewerk. Together, they took a honeymoon cruise via North German Lloyd to Italy. While on tour in Naples and Rome, the Sorges were deeply moved by the pious Catholicism of the Italian people.

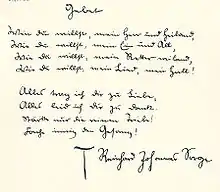

In a letter to his mother, Sorge wrote,

"In the Revelation of St. John the heavenly visions are so depicted -- golden censers are swung; people kneel and worship in solemn vesture, with crowns on their heads, a woman clothed with the sun appears (Mary). See, all quite Catholic, and that from St. John, a favorite disciple of the Lord. Our earthly Church must be a copy of the heavenly."[11]

Conversion

After returning to Germany, the Sorges were received into the Roman Catholic Church at Jena in September 1913. He subsequently wrote to a friend,

"My soul was always inherently Christian, but I was misled by Nietzsche, entangled in suns and stars. In Der Bettler, I invoked the Name of God many a time quite unconsciously, and yet thought myself a fervent disciple of Nietzsche, who denies God's very existence."[12]

To the distress of Germany's Expressionist movement, Sorge vowed, "Thenceforth my pen has been and forever will be Christ's stylus—until my death."[13] As a result, his subsequent writings were all centered on fervently religious themes. Admirers of avant garde theater, however, were disappointed by the more traditional stagecraft of Sorge's subsequent plays.[14]

Sorge also succeeded in winning over many of his friends and relatives to Catholicism. Sorge had less success in his evangelizing letters to Ranier Maria Rilke, Stefan George, and his former mentor, Richard Dehmel.

Military service in the First World War and death

Sorge was conscripted into the Prussian Army in 1915 and assigned to the 6th Company of Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 69, which was attached to the 15th Reserve Division of the Imperial German Army along the Western Front. By 1916, Sorge had been promoted to the rank of Gefreiter,[15] the equivalent to Lance Corporal.[16]

According to his letters to Susanne and a subsequent letter she received from his battalion's Jesuit military chaplain, Sorge used his devout Catholic beliefs in order to deal with the horrors of trench warfare. He also spent much of his free time trying to win his fellow soldiers over to Roman Catholicism. While serving at the Somme, Sorge's thighs were shattered by an exploding grenade.[17] He died the same day, 20 July 1916, at a field dressing station in the ruins of Ablaincourt.[18] A short time before, he had written to Susanne,

"I suppose it is the imperfection of it all that I feel, and then the longing for our life together breaks through; but soon my soul is soothed and consoled by the conviction that this period has to be, that without it there can be no perfection."[19]

Burial

According to the website of the German War Graves Commission, Reinhard Johannes Sorge lies buried in a communal war grave at the Vermandovillers German war cemetery, located near the battlefield where he died.[20] The remains of the German Jewish Expressionist poet Alfred Lichtenstein, who similarly fell fighting for the last Kaiser in 1914, and a total of 22,632 fallen German soldiers from World War I lie in the same cemetery.

Legacy

On 23 December 1917, legendary Austrian stage director Max Reinhardt presided over the world premiere of Sorge's Kleist Prize-winning play Der Bettler, which had long been, "a succès de scandale, an innovation, changing the course of theatrical history with its revolutionary staging techniques."[21]

According to Michael Paterson, "The genius of the 20-year old Sorge already showed the possibilities of abstract staging, and Reinhardt in 1917, simply by following Sorge's stage directions, was to become the first director to present a play in wholly Expressionist style."[22]

The subsequent influence of Reinhard Sorge upon Christian poetry in the Germanosphere was so overwhelming during the Interwar Period, that Rev. B. O'Brien compared Sorge to Francis Thompson.

On 4 July 2016 the centenary of Sorge's death was commemorated in a multinational ceremony at Belloy-en-Santerre, alongside Allied war poets Alan Seeger and Camil Campanyà, who fell serving with the French Foreign Legion during the same battle.[23]

Writings

Stage Plays

- Der Bettler. Eine dramatische Sendung (1912);

- Guntwar. Die Stunde eines Propheten (1914);

- Metanoeite. Drei Mysterien (1915);

- König David (1916);

- Mystische Zwiesprache (1922);

- Der Sieg des Christos. Eine Vision (1924);

- Der Jüngling (frühere Dramen umfassend;1925);

Poetry

- Mutter der Himmel. Ein Sang in zwölf Gesängen (1917);

- Gericht über Zarathustra. Vision (1921);

- Preis der Unbefleckten. Sang über die Begegnung zu Lourde's (1924);

- Nachgelassene Gedichte (1925);

Collected works

- Werke, 3 Volumes (1962–67).

Others

- Bekenntnisse und Lobpreisungen, edited by Otto Karrera (München, 1960).

Resources

- Rev. B. O'Brien, S.J., "From Nietzsche to Christ: Reinhard Johannes Sorge," Irish Monthly, December 1932, pages 713-722.

- Lance Corporal, Reserve Infantry Regiment 69, 6 Kompagnie; Prussian casualty list No. 607 of 15 August 1916, p 14057/Deutsche casualty list.

Notes

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 144.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 144.

- "From Nietzsche to Christ," page 714.

- "From Nietzsche to Christ", page 716.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 144.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Pages 144-145.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 145.

- Walter H. Sokel (1959), The Writer in Extremis, Stanford University Press.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 144.

- "From Nietzsche to Christ", .

- "From Nietzsche to Christ", page 719.

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 144.

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 144.

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 144.

- Gefreiter, Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 69, 6. Kompagnie; Preußische Verlustliste Nr. 607 vom 15. August 1916, S. 14057/Deutsche Verlustliste. (prussian R.I.R. 69/15th Reserve Division/German casualty roll entry)

- Jack Sheldon (2007), The German Army on the Somme; 1914-1916, Pen & Sword Military Classics. Page 401.

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 144.

- Gefreiter, Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 69, 6. Kompagnie; Preußische Verlustliste Nr. 607 vom 15. August 1916, S. 14057/Deutsche Verlustliste. (Pussian R.I.R. 69/15th Reserve Division/German casualty roll entry)

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 144.

- "Vermandovillers, Département Somme, 22632 German Casualties of the First World War (in German)". Archived from the original on 2010-11-03. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- Tim Cross, "The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights," University of Iowa Press, 1989. Page 144.

- "The Lost Voices of World War I," page 145.

- The Catalan Government pays homage to the Catalan volunteers of the First World War at Belloy en Santerre 4 July 2016.

External links

- Zeno.org Reinhard Sorge: Biography and Writings Online (In German)

- Reinhard Sorge at Project Gutenburg (In German)

- Reinhard Sorge in the German National Library Catalogue

- Reinhard Sorge: A German Poet in Switzerland (In German)

- Catalogue of Sorge Manuscripts in the Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach am Neckar

- Rev. B. O'Brien, S.J., "From Nietzsche to Christ: Reinhard Johannes Sorge," Irish Monthly, December 1932, pages 713-722.

- Biblioteca Augustana