Religion in Iran

Religion in Iran has been shaped by multiple religions and sects over the course of the country's history. Zoroastrianism was the main followed religion during the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BC), Parthian Empire (247 BC - 224 AD), and Sasanian Empire (224-651 AD). Another Iranian religion known as Manichaeanism was present in Iran during this period. Jewish and Christian communities (the Church of the East) thrived, especially in the territories of northwestern, western, and southern Iran—mainly Caucasian Albania, Asoristan, Persian Armenia, and Caucasian Iberia. A significant number of Iranian peoples also adhered to Buddhism in what was then eastern Iran, such as the regions of Bactria and Sogdia.

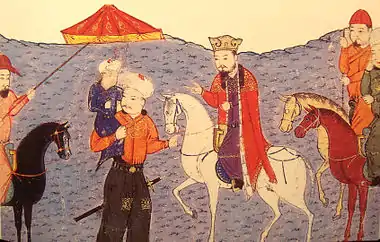

Between 632-654 AD, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Iran, and the next two centuries of Umayyad and Abbasid rule (as well as native Iranian rule during the Iranian Intermezzo) would see Iran, although initially resistant, gradually adopt Islam as the nation's predominant faith. Sunni Islam was the predominant form of Islam before the devastating Mongol conquest (1219-1221 AD), but with the advent of the Safavid Empire (1501-1736) Shi'ism became the predominant faith in Iran.[1]

There have been a number of surveys on the current religious makeup of Iran. Most show a very high percentage of Iranian identifying as Muslim -- 99.98% (the official 2011 Iranian government census, whose numbers were used by the CIA World Factbook),[2] 96.6% (2020 survey by the World Values Survey),[3] 96%, with 85% of the overall population identifying as Shias and with 11% of the population identifying as Sunnis (The Gulf/2000 Project under the University of Columbia), although one, a 2020 survey conducted by GAMAAN exclusively on the internet, found only about 40% of Iranians identifying as Muslim.[4]

Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism are officially recognized and protected, and have reserved seats in the Iranian parliament.[5] Iran is home to the second largest Jewish community in the Muslim world and the Middle East.[6] The three largest non-Muslim religious minorities in Iran are the followers of the Baháʼí Faith, Christianity and Yarsani.[7] Starting sometime after 1844, The Baháʼí community, became the largest religious minority group in Iran,[8] has been persecuted during its existence and is not recognized as a faith by the Iranian government.[9][10][11][12]

History

Prehistory

The first known religious traditions in Iran traditions developed over time into Zoroastrianism.

Zoroastrianism

The written Zoroastrian holy book, called the Avesta, dates back to between 600 and 1000 BC, but the traditions it is based on are more ancient.[13] It was the predominant religion in the region until the Muslims conquered Persia.

Zoroastrians in Iran have had a long history reaching back thousands of years, and are the oldest religious community of Iran that has survived to the present day. Prior to the Muslim Arab invasion of Persia (Iran), Zoroastrianism had been the primary religion of Iranian peoples. Zoroastrians mainly are ethnic Persians and are concentrated in the cities of Tehran, Kerman, and Yazd. According to the Iranian census data from 2011 the number of Zoroastrians in Iran was 25,271.[14] Reports in 2022 show a similar figure.[7]

This oppression has led to a massive diaspora community across the world, in particular, the Parsis of India, whose numbers significantly higher than the Zoroastrians in Iran.

Mithra (Avestan: 𐬨𐬌𐬚𐬭𐬀 Miθra, Old Persian: 𐎷𐎰𐎼 Miça) is the Zoroastrian Divinity (yazata) of Covenant, Light, and Oath. In addition to being the divinity of contracts, Mithra is also a judicial figure, an all-seeing protector of Truth, and the guardian of cattle, the harvest, and of the Waters.

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was a major religion[15] founded by the Iranian[16] prophet Mani (Middle Persian Mānī, New Persian: مانی Mānī, Syriac Mānī, Greek Μάνης, c. 216–274 AD) in the Sasanian Empire but has been extinct for many centuries.[17][18] It originated in third century Mesopotamia[19] and spread rapidly throughout North Africa to Central Asia during the next several centuries.

Mani was a Babylonian prophet born in 216 C.E. near the city of Ctesiphon. Not long after his birth, Mani's father, Pattikios, heard a voice commanding him to join a communitarian sect that resided in the marshes south of the city and so he abandoned his former life and took his son with him. Mani grew up in the sect and occasionally experienced “revelations” meditated through an angelic figure. These revelations led to his increasingly disruptive behavior and he was eventually forced to leave the sect and start a new phase of his life.[19]

Inspired by the messages he received from the angelic figure, Mani began his missionary journeys to spread his new religion. Gaining the favor of the Sasanian ruler in Mesopotamia was an important factor for the early success of his work. Over time, Mani built a following and a number of his trusted disciples were dispatched to the West to Syria, Arabia, and Egypt and added more converts to this rapidly expanding religion.[19]

By the end of the third century Manichaeism reached the attention of the Roman Empire who viewed it as a “Persian aberration” with followers who were “despicable deviants”.[20] Meanwhile, in Mesopotamia, rule was taken over by a new, less tolerant regime who imprisoned and executed Mani as an offender against Zoroastrian orthodoxy[21] Consistent waves of persecution from Christians, Zoroastrians, and Muslims, Manichaeism was eventually eradicated as a formal religious affiliation within Byzantine and Islamicate realms.[22]

Manichaeism taught an elaborate dualistic cosmology describing the struggle between a good, spiritual world of light, and an evil, material world of darkness.[23]

Islam

Islam has been the official religion and part of the governments of Iran since the Arab conquest of Iran c. 640 AD.[Note 1] It took another few hundred years for Shia Islam to gather and become a religious and political power in Iran. In the history of Shia Islam the first Shia state was Idrisid dynasty (780–974) in Maghreb, a region of north west Africa. Then the Alavids dynasty (864–928 AD) became established in Mazandaran (Tabaristan), in northern Iran. The Alavids were of the Zaidiyyah Shia (sometimes called "Fiver".)[24] These dynasties were local. But they were followed by two great and powerful dynasties: Fatimid Caliphate which formed in Ifriqiya in 909 AD and the Buyid dynasty emerged in Daylaman, in north central Iran, about 930 AD and then extended rule over central and western Iran and into Iraq until 1048 AD. The Buyid were also Zaidiyyah Shia. Later Sunni Islam came to rule from the Ghaznavids dynasty (975–1187 AD) through to the Mongol invasion and establishment of the Ilkhanate which kept Shia Islam out of power until the Mongol ruler Ghazan converted to Shia Islam in 1310 AD and made it the state religion.[25]

The distinction between Shia groups have distinctions between Fiver, Sevener and Twelver, derived from their belief in how many divinely ordained leaders there were who are descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah and his son-in-law Ali. These Imams are considered the best source of knowledge about the Quran and Islam, the most trusted carriers and protectors of Muḥammad's Sunnah (habit or usual practice) and the most worthy of emulation. In addition to the lineage of Imams, Twelvers have their preferred hadith collections – The Four Books – which are narrations regarded by Muslims as important tools for understanding the Quran and in matters of jurisprudence. For Twelvers the lineage of Imams are known as the Twelve Imams. Of these Imams, only one is buried in Iran – at the Imam Reza shrine, for Ali ar-Ridha who lived from 765 to 818 AD, before any Shi'a dynasties arose in Iran. The last Imam recognized by Twelvers, Muhammad al-Mahdi, was born in 868 AD as the Alavids spread their rule in Iran while in conflict with Al-Mu'tamid, the Abbasid Caliph at the time. Several Imams are buried in Iraq, as sites of pilgrimage, and the rest are in Saudi Arabia. In addition two of the Five Martyrs of Shia Islam have connections to Iran – Shahid Thani (1506–1558) lived in Iran later in life, and Qazi Nurullah Shustari (1549–1610) was born in Iran. The predominant school of theology, practice, and jurisprudence (Madh'hab) in Shia Islam is Jafari established by Ja'far as-Sadiq. There is also a community of Nizari Ismailis in Iran who recognise Aga Khan IV as their Imam.[26]

Although Shias have lived in Iran since the earliest days of Islam,[27] and there had been Shia dynasties in parts of Iran during the 10th and 11th centuries, according to Mortaza Motahhari the majority of Iranian scholars and masses remained Sunni until the time of the Safavids.[28]

However, there are four high points in the history of Shia in Iran that expanded this linkage:

- First, the migration of a number of persons belonging to the tribe of the Ash'ari from Iraq to the city of Qum towards the end of the 7th century AD, which is the period of establishment of Imami Shi‘ism in Iran.

- Second, the influence of the Shia tradition of Baghdad and Najaf on Iran during the 11th to 12th centuries AD.

- Third, the influence of the school of Hillah on Iran during the 14th century AD.

- Fourth, the influence of the Shi‘ism of Jabal Amel and Bahrain on Iran during the period of establishment of the Safavid rule.[29]

In 1501, the Safavid dynasty established Twelver Shia Islam as the official state religion of Iran.[30] In particular after Ismail I captured Tabriz in 1501 and established Safavids dynasty, he proclaimed Twelver Shiʿism as the state religion, ordering conversion of the Sunnis. The population of what is nowadays Azerbaijan was converted to Shiism the same time as the people of what is nowadays Iran.[1] Although conversion was not as rapid as Ismail's forcible policies might suggest, the vast majority of those who lived in the territory of what is now Iran and Azerbaijan did identify with Shiism by the end of the Safavid era in 1722. As most of Ismail's subjects were Sunni he enforced official Shi'ism violently, putting to death those who opposed him. Thousands were killed in subsequent purges.In some cases entire towns were eliminated because they were not willing to convert from Sunni Islam to Shia Islam.[31] Ismail brought Arab Shia clerics from Bahrain, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon in order to preach the Shia faith.[32] Ismail's attempt to spread Shia propaganda among the Turkmen tribes of eastern Anatolia prompted a conflict with the Sunnite Ottoman Empire. Following Iran's defeat by the Ottomans at the Battle of Chaldiran, Safavid expansion faltered, and a process of consolidation began in which Ismail sought to quell the more extreme expressions of faith among his followers.[33] While Ismail I declared Shiism as the official state religion, it was, in fact, his successor Tahmasb who consolidated the Safavid rule and spread Shiʿism in Iran. After a period of indulgence in wine and the pleasures of the harem, he turned pious and parsimonious, observing all the Shiʿite rites and enforcing them as far as possible on his entourage and subjects.[31] Under Abbas I, Iran prospered. Succeeding Safavid rulers promoted Shi'a Islam among the elites, and it was only under Mullah Muhammad Baqir Majlisi - court cleric from 1680 until 1698 - that Shia Islam truly took hold among the masses.[34]

Then there were successive dynasties in Iran – the Afsharid dynasty (1736–1796 AD) (which mixed Shi'a and Sunni), Zand dynasty (1750–1794 AD) (which was Twelver Shia Islam), the Qajar dynasty (1794–1925 AD) (again Twelver). There was a brief Iranian Constitutional Revolution in 1905–11 in which the progressive religious and liberal forces rebelled against theocratic rulers in government [35] who were also associated with European colonialization and their interests in the new Anglo-Persian Oil Company.The secularist efforts ultimately succeeded in the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979 AD). The 1953 Iranian coup d'état was orchestrated by Western powers[36] which created a backlash against Western powers in Iran, and was among the background and causes of the Iranian Revolution to the creation of the Islamic republic.

From the Islamization of Iran the cultural and religious expression of Iran participated in the Islamic Golden Age from the 9th through the 13th centuries AD, for 400 years.[37] This period was across Shia and Sunni dynasties through to the Mongol governance. Iran participated with its own scientists and scholars. Additionally the most important scholars of almost all of the Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or lived in Iran including most notable and reliable Hadith collectors of Shia and Sunni like Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj and Hakim al-Nishaburi, the greatest theologians of Shia and Sunni like Shaykh Tusi, Al-Ghazali, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi and Al-Zamakhshari, the greatest Islamic physicians, astronomers, logicians, mathematicians, metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists like Al-Farabi and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, the Shaykhs of Sufism like Rumi, Abdul-Qadir Gilani – all these were in Iran or from Iran.[38] And there were poets like Hafiz who wrote extensively in religious themes. Ibn Sina, known as Avicenna in the west, was a polymath and the foremost Islamic physician and philosopher of his time.[39] Hafiz was the most celebrated Persian lyric poet and is often described as a poet's poet. Rumi's importance transcends national and ethnic borders even today.[40] Readers of the Persian and Turkish language in Iran, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan see him as one of their most significant classical poets and an influence on many poets through history.[41] In addition to individuals, whole institutions arose – Nizamiyyas were the medieval institutions of Islamic higher education established by Nizam al-Mulk in the 11th century. These were the first well-organized universities in the Muslim world. The most famous and celebrated of all the nizamiyyah schools was Al-Nizamiyya of Baghdad (established 1065), where Nizam al-Mulk appointed the distinguished philosopher and theologian, al-Ghazali, as a professor. Other Nizamiyyah schools were located in Nishapur, Balkh, Herat, and Isfahan.

While the dynasties avowed either Shia or Sunni, and institutions and individuals claimed either Sunni or Shia affiliations, Shia–Sunni relations were part of Islam in Iran and continue today when Ayatollah Khomeini also called for unity between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

Sunni Islam

Sunni Muslims are the second-largest religious group in Iran.[42] Specifically, Sunni Muslims came to power in Iran after the period when Sunni were distinguished from Shi'a by the Ghaznavids who ruled Iran from 975 to 1186 AD, followed by the rule of the Great Seljuq Empire and the Khwarazm-Shah dynasty which ruled Iran until the Mongol invasion of Iran. Sunni Muslims returned to power when Ghazan converted to Sunni Islam.

About 9%[43] of the Iranian population are Sunni Muslims—mostly Larestani people (Khodmooni) from Larestan, Kurds in the northwest, Arabs and Balochs in the southwest and southeast, and a smaller number of Persians, Pashtuns and Turkmens in the northeast.

Sunni websites and organizations complain about the absence of any official records regarding their community and believe their number is much greater than what is usually estimated. Demographic changes have become an issue for both sides. Scholars on either side speak about the increase in the Sunni population and usually issue predictions regarding demographic changes in the country. One prediction, for example, claims that the Sunnis will be the majority in Iran by 2030.[44]

The mountainous region of Larestan is mostly inhabited by indigenous Sunni Persians who did not convert to Shia Islam during the Safavids because the mountainous region of Larestan was too isolated. The majority of Larestani people are Sunni Muslims,[45][46][47] 30% of Larestani people are Shia Muslims. The people of Larestan speak the Lari language, which is a southwestern Iranian language closely related to Old Persian (pre-Islamic Persian) and Luri.[48] Sunni Larestani Iranians migrated to the Arab states of the Persian Gulf in large numbers in the late 19th century. Some Sunni Emirati, Bahraini and Kuwaiti citizens are of Larestani ancestry.

Iran's Ministry of Health announced that all family-planning programs and procedures would be suspended. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei called on women to have more children to boost the country's population to 150–200 million. Contraceptive policy made sense 20 years ago, he said, but its continuation in later years was wrong. Numerous speculations have been given for this change in policy: that it was an attempt to show the world that Iran is not suffering from sanctions; to avoid an aging population with rising medical and social-security costs; or to return to Iran's genuine culture. Some speculate that the new policy seeks to address the Supreme Leader's concerns that Iran's Sunni population is growing much faster than its Shia one (7% growth in Sunni areas compared to 1–1.3% in Shia areas).[49][50]

The predominant school of theology and jurisprudence (Madh'hab) among Sunnis in Iran is Hanafi, established by Abu Hanifa.

According to Mehdi Khalaji, Salafi Islamic thoughts have been on the rise in Iran in recent years. Salafism alongside extremist Ghulat Shia sects has become popular amongst some Iranian youth, who connect through social media and underground organizations. The Iranian government views Salafism as a threat and does not allow Salafis to build mosques in Tehran or other large cities due to the fear that these mosques could be infiltrated by extremists.[51]

It is reported that members of religious minority groups, especially Sunni Muslims who supported rebels during the Syrian Civil War, are increasingly persecuted by authorities. During 2022, there were several reports of government harassment, discrimination and detention of citizens because of their religious beliefs.[7][52]

In 2022, Mehdi Farmanian, chancellor for research at the Qom-based University of Religions and Denominations, claimed that Sunnis enjoy religious freedoms in Iran by indicating that they possess 15000 mosques, 500 religious schools and 100 religious institutions, but critical observers note that Sunnis still aren't treated as equal citizens, for instance not getting the same amount of budget or the fact that their numbers are under-estimated, Baloch Sunni cleric and leader Abdolhamid Ismaeelzahi putting them at 20% of the population (instead of the official 10%).[53]

Sufism

The Safaviya sufi order, originates during the Safavid dynasty c. 700 AD. A later order in Persia is the Chishti. The Nimatullahi are the largest Shi'i Sufi order active throughout Iran and there is the Naqshbandi, a Sunni order active mostly in the Kurdish regions of Iran. The Oveyssi-Shahmaghsoudi order is the largest Iranian Sufi order which currently operates outside of Iran.

Famous Sufis include al-Farabi, al-Ghazali, Rumi, and Hafiz. Rumi's two major works, Diwan-e Shams and Masnavi, are considered by some to be the greatest works of Sufi mysticism and literature.

Since the 1979 Revolution, Sufi practices have been repressed by the Islamic Republic, forcing some Sufi leaders into exile.[54][55]

While no official statistics are available for Sufi groups, there are reports that estimate their population between two and five million (between 3–7% of the population).[42]

Christianity

Christianity has a long history in Iran, dating back to the very early years of the faith. And Iran's culture is thought to have affected Christianity by introducing the concept of the Devil to it.[56] There are some very old churches in Iran – perhaps the oldest and largest is the Monastery of Saint Thaddeus, which is also called the Ghara Kelissa (the Black Monastery), south of Maku.[57] By far the largest group of Christians in Iran are Armenians under the Armenian Apostolic Church which has between 110,000,[58] 250,000,[59] and 300,000 adherents.[60] There are many hundreds of Christian churches in Iran, with at least 600 being active serving the nation's Christian population.[61] As of early 2015, the Armenian church is organized under Archbishop Sepuh Sargsyan, who succeeded Archbishop Manukian, who was the Armenian Apostolic Archbishop since at least the 1980s.[62][63][64] Unofficial estimates for the Assyrian Christian population range between 20,000,[65][66] and 70,000.[67][68] Christian groups outside the country estimate the size of the Protestant Christian community to be fewer than 10,000, although many may practice in secret.[42] There are approximately 20,000 Christians Iranian citizens abroad who left after the 1979 revolution.[69] Christianity has always been a minority religion, overshadowed by the majority state religions—Zoroastrianism in the past, and Shia Islam today. Christians of Iran have played a significant part in the history of Christian mission. While always a minority the Armenian Christians have had an autonomy of educational institutions such as the use of their language in schools.[63] The Government regards the Mandaeans as Christians, and they are included among the three recognized religious minorities; however, Mandaeans do not consider themselves Christians.[42]

Christian population estimations range between 300,000[61] and 370,000[61] adherents; one estimate suggests a range between 100,000 and 500,000 Christian believers from a Muslim background living in Iran.[70] Of the three non-Muslim religions recognized by the Iranian government, the 2011 General Census indicated that Christianity was the largest in the nation.[71] Evangelical Christianity is growing at 19.6% annually, according to Operation World, making Iran the country with the highest annual Evangelical growth rate.[72]

The small evangelical Protestant Christian minority in Iran has been subject to Islamic "government suspicion and hostility" according to Human Rights Watch at least in part because of its "readiness to accept and even seek out Muslim converts." According to Human Rights Watch in the 1990s, two Muslim converts to Christianity who had become ministers were sentenced to death for apostasy and other charges.[73] There still have not been any reported executions of apostates. However many people, such as Youcef Nadarkhani, Saeed Abedini have been recently harassed, jailed and sentenced to death for Apostasy. Iran is number nine on Open Doors’ 2022 World Watch List, an annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most extreme persecution.[74]

Mandaeism

Mandaeism, sometimes also known as Sabianism (after the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran, a name historically claimed by several religious groups),[75] is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion, whose adherents, the Mandaeans, follow John the Baptist also known as Yaḥyā ibn Zakarīyā. The number of Iranian Mandaeans is a matter of dispute. In 2009, there were an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 Mandaeans in Iran, according to the Associated Press,[76] while Alarabiya has put the number of Iranian Mandaeans as high as 60,000 in 2011.[77]

Until the Iranian Revolution, Mandaeans had mainly been concentrated in Khuzestan province, where the community historically existed side by side with the local Arab population. They had mainly practiced the profession of goldsmith, passing it from generation to generation.[77] After the fall of the shah, its members faced increased religious discrimination, and many sought new homes in Europe and the Americas.

In 2002 the US State Department granted Iranian Mandaeans protective refugee status; since then roughly 1,000 have emigrated to the US,[76] now residing in cities such as San Antonio, Texas.[78] On the other hand, the Mandaean community in Iran has increased in size over the last decade, because of the exodus from Iraq of the main Mandaean community, which once was 60,000–70,000 strong.

Yarsanism

The Yarsan or Ahl-e Haqq is a syncretic religion founded by Sultan Sahak in the late 14th century in western Iran.[79] It is difficult to find the accurate number of Yarsanis in Iran as they are not recognized by the Government, but the Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa estimates their total number at 1,000,000 in 2004,[80] and "human rights organizations and news outlets" at between one and three million according to the US Department of State in 2022.[7] They are mostly ethnic Goran Kurds, and primarily found in western Iran and Iraq,[81][82][83] though there are also smaller groups of Persian, Lori, Azeri and Arab adherents.[84] The Islamic Republican government often "considers" Yarsanis to be "Shia Muslims practicing Sufism", but Yarsanis believe their faith is distinct, calling it Yarsan, Ahl–e–Haq or Kakai. Because only citizens registered in one of the IRIs approved religions may obtain government services, Yarsanis often register as Shia.[7]

Judaism

Judaism is one of the oldest religions practiced in Iran and dates back to the late biblical times. The biblical books of Isaiah, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles, and Esther contain references to the life and experiences of Jews in Persia.

Iran is said to support by far the largest Jewish population of any Muslim country,[85] although the Jewish communities in Turkey and Azerbaijan are of comparable size. In recent decades, the Jewish population of Iran has been reported by some sources to be 25,000,[86][87][88] though estimates vary, as low as 11,000 [89] and as high as 40,000.[90] According to the Iranian census data from 2011 the number of Jews in Iran was 8,756, much lower than the figure previously estimated.[14]

Emigration has lowered the population of 75,000 to 80,000 Jews living in Iran prior to the 1979 Islamic revolution.[91] According to The World Jewish Library, most Jews in Iran live in Tehran, Isfahan (3,000), and Shiraz. BBC reported Yazd is home to ten Jewish families, six of them related by marriage; however, some estimate the number is much higher. Historically, Jews maintained a presence in many more Iranian cities.

Today, the largest groups of Jews from Iran are found in the United States, which is home to approximately 100,000 Iranian Jews, who have settled especially in the Los Angeles area and New York City area.[92] Israel is home to 75,000 Iranian Jews, including second-generation Israelis.[93]

Buddhism

Buddhism in Iran dates back to the 2nd century, when Parthians, such as An Shigao, were active in spreading Buddhism in China. Many of the earliest translators of Buddhist literature into Chinese were from Parthia and other kingdoms linked with present-day Iran.[94]

Sikhism

There is a very small community of Sikhs in Iran numbering about 60 families mostly living in Tehran. Many of them are Iranian citizens. They also run a gurdwara in Tehran.[95]

Sikhism in Iran is so uncommon amongst the families that many citizens of Tehran are not even aware of the gurdwara in their city. This is due to Tehran being the capitol of Iran and the reputation that Iran has of being intolerant towards religions other than Shia. The United Nations has repeatedly accused Iran of persecuting citizens based on their religion. Although the Sikhs of Iran experience persecution like many other minority religions they are still envied by those other minority groups. Regular worshippers in Tehran have even stated that they feel no discrimination at all from fellow citizens of Tehran.[96]

Sikhs began migrating to Iran around the start of the 20th century from British controlled areas of India that eventually became Pakistan. They originally settled in Eastern Iran and slowly moved towards Tehran. Before the Iranian Revolution of 1979 the Sikh community was believed to be as many as 5,000 strong, but after the revolution and the Iraqi war the numbers declined. Part of this exodus out of Iran was attributed to the new laws and restrictions on religion put in place by the new Iranian government.[96]

Currently there are four gurdwaras in Iran. Tehran, Mashhad, Zahidan, and Bushehr. Every Friday morning and evening they participate in prayers, and Guru-Ka-Langer every Friday after the Akhand Path. They also participate in community service by establishing schools, and teaching young students Punjabi and Dharmik (Divinity).[97] With the dwindling number of Sikhs in the area the school attached to the gurdwara's in Iran have been opened to non-Sikhs. The majority of the students still come from India or surrounding countries.[96]

Demographics

Surveys of current demographics

A 2020 survey by the World Values Survey found that 96.6% of Iranians believe in Islam.[3] According to the CIA World Factbook, around 90–95% of Iranian Muslims associate themselves with the Shia branch of Islam, the official state religion, and about 5–10% with the Sunni and Sufi branches of Islam.[43] According to the 2011 Iranian census, 99.98% of Iranians believe in Islam, while the rest of the population believe in other officially recognized minority religions: Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism.[98] Because irreligion and some other religions (including the Baháʼí Faith) are not recognized by the Iranian government, and because apostasy from Islam may be subject to capital punishment, governmental figures are likely to be distorted.[99]

On the other hand, another 2020 survey conducted online by an organization based outside of Iran (GAMAAN) found a much smaller percentage of Iranians identifying as Muslim (32.2% as Shia, 5.0% as Sunni, and 3.2% as Sufi), and a significant fraction not identifying with any organized religion - this shift is primarily the result of a backlash against more than forty years of theocracy (22.2% identifying as "None," and some others identifying as atheists (8.8%), spiritual (7.1%), agnostics (5.8%), and secular humanists). 7.7% said they were Zoroastrians, while 1.5% said they were Christian.[4][100][101][102][103]

Statistics on religious belief and religiosity

The constitution of Iran limits the number of recognized non-Islamic religions to three - Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians - and the laws of the Islamic Republic forbid atheism and conversion by Muslims to another religion.[7] Obtaining accurate data on religious belief in Iran presents challenges to pollsters because Iranians do not always feel "comfortable sharing their opinions with strangers".[104]

| Year | Results |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 99.38% of Iranians were Muslims.[105] |

| Source | Year | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Crisis Group | 2005 | Islam was the religion of 99.6% of Iranians of which approximately 89% are Shia – almost all of whom are Twelvers.[106] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2009 | Of all Iranian Muslims, 90-95% are Shi’ites.[107] | |

| CIA World Factbook | 2011 | Almost all Iranians as Muslim, with 90–95% thought to associate themselves with the official state religion – Shia Islam – and about 5–10% with the Sunni and Sufi branches of Islam.[108] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 99.8% of Iranians identifying as Muslim.[109] | |

| Gallup Poll | 2016 | Using "a mix of telephone and face-to-face interviews", 86% of Iranians considered themselves religious, up from 76% in 2006.[104] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2018 | 78% of Iranians believe religion to be very important in their lives. The same study also found that 38% of Iranians attend worship services weekly.[110] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2019 | 87% of Iranians pray on a daily basis, which was the second-highest percentage in Asia-Pacific, after Afghanistan (96%) and ahead of Indonesia (84%).[111] | |

| World Value Survey | 2020 | 96.5% of Iranians Identified as Muslims.[3] | |

| GAMAAN | 2020 | Survey conducted online on 50,000 Iranians and found 32% identified as Shia, 5% as Sunni and 3% as Shia Sufi Muslim (Irfan Garoh). 22.2% of respondents identified their religion as "None," with an additional 8.8% of respondents identifying as atheists, 5.8% identifying as agnostics, and 2.7% identifying as humanists. A small minority of Iranians said they belonged to other religions, including Zoroastrianism (7.7%), Christianity (1.5%), the Baháʼí Faith (0.5%), and Judaism (0.1%). A further 7.1% of respondents identified themselves as "spiritual."[4][112][113][Note 2] |

Non-Muslim religions

There are several major religious minorities in Iran, Baháʼís (est. 300,000-350,000)[7][115][116] and Christians (est. 300,000[61] – 370,000[61] with one group, the Armenians of the Armenian Apostolic Church, composing between 200,000 and 300,000[60][62]) being the largest. Smaller groups include Jews, Zoroastrians, Mandaeans, and Yarsan, as well as local religions practiced by tribal minorities.[42][117]

Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians are officially recognized and protected by the government. For example, shortly after his return from exile in 1979, at a time of great unrest, the revolution's leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering that Jews and other minorities be treated well.[85][118]

Contemporary legal status

The constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran recognizes Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism as official religions. Article 13 of the Iranian Constitution, recognizes them as People of the Book and they are granted the right to exercise religious freedom in Iran.[115][119] Five of the 270 seats in parliament are reserved for each of these three religions.

In 2017 a controversy erupted around the reelection of a Zoroastrian municipal councilor in Yazd, because no clear legislation existed with regard to the matter. "On April 15, about one month before Iran's local and presidential elections", Ahmad Jannati, head of the Guardian Council, had "issued a directive demanding that non-Muslims be disqualified from running in the then-upcoming city and village council elections in localities where most of the population are Muslims".[120] On November 26, 2017, Iranian lawmakers approved the urgency of a bill that would give the right for members of the religious minorities to nominate candidates for the city and village councils elections. The bill secured 154 yes votes, 23 no votes and 10 abstentions. A total of 204 lawmakers were present at the parliament session.[121]

On the other hand, senior government posts are reserved for Muslims. Members of all minority religious groups, including Sunni Muslims, are barred from being elected president. Jewish, Christian and Zoroastrian schools must be run by Muslim principals.[122]

Until recently the amount of monetary compensation which was paid to the family for the death of a non-Muslim victim was (by law) lower than the amount of monetary compensation which was paid to the family for the death of a Muslim victim. Conversion to Islam is encouraged by islamic inheritance laws, which mean that by converting to Islam, converts will inherit the entire share of their parents' (or even the entire share of their uncle's) estate if their siblings (or cousins) remain non-Muslim.[123]

Collectively, these laws, regulations and general discrimination and persecution have led to Iran's non-Muslim population falling dramatically. For example, the Jewish population in Iran dropped from 80,000 to 30,000 in the first two decades following the revolution (roughly 1978–2000).[118] By 2012, it had dwindled below 9,000.[124]

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith has been persecuted since its inception in Iran.[9][10][11][125][126] Since the 1979 revolution the persecution of Baháʼís has increased with oppression, the denial of civil rights and liberties, and the denial of access to higher education and employment.[9][127][125][126][128] There were an estimated 350,000 Baháʼís in Iran in 1986.[127] The Baháʼís are scattered in small communities throughout Iran with a heavy concentration in larger cities.[27] Most Baháʼís are urban, but there are some Baháʼí villages,[27] especially in Fars and Mazandaran. The majority of Baháʼís are Persians,[27] but there is a significant minority of Azeri Baháʼís,[27] and there are even a few among the Kurds. Baháʼís are neither recognized nor protected by the Iranian constitution.

The Baháʼí Faith originated in Iran during the 1840s as a messianic movement out of Shia Islam. Opposition arose quickly, and Amir Kabir, as prime-minister, regarded the Bábis as a threat and ordered the execution of the founder of the movement, the Báb and killing of as many as 2,000 to 3,000 Babis.[129] As another example two prominent Baháʼís were arrested and executed circa 1880 because the Imám-Jum'ih at the time owed them a large sum of money for business relations and instead of paying them he confiscated their property and brought public ridicule upon them as being Baháʼís.[130] Their execution was committed despite observers testifying to their innocence.

The Shia clergy, as well as many Iranians, have continued to regard Baháʼís as heretics (the founder of Baháʼí, Baháʼu'lláh, preached that his prophecies superseded Muhammad's), and consequently Baháʼís have encountered much prejudice and have often been the objects of persecution. The situation of the Baháʼís improved under the Pahlavi shahs when the government actively sought to secularize public life, but there were still organizations actively persecuting the Baháʼís (in addition curses children would learn decrying the Báb and Baháʼís).[131] The Hojjatieh was a semi-clandestine traditionalist Shia organization founded by Muslim clerics[131] on the premise that the most immediate threat to Islam was the Baháʼí Faith.[132] In March to June 1955, the Ramadan period that year, a widespread systematic program was undertaken cooperatively by the government and the clergy. During the period they destroyed the national Baháʼí Center in Tehran, confiscated properties and made it illegal for a time to be Baháʼí (punishable by 2 to 10-year prison term).[133] The founder of SAVAK (the secret police during the rule of the shahs), Teymur Bakhtiar, took a pick-ax to a Baháʼí building himself at the time.[134]

The social situation of the Baháʼís was drastically altered after the 1979 revolution. The Hojjatieh group flourished during the 1979 revolution but was forced to dissolve after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini speech on 12 August 1983. However, there are signs of it reforming circa 2002–04.[134] Beyond the Hojjatieh group, the Islamic Republic does not recognize the Baháʼís as a religious minority, and they have been officially persecuted, "some 200 of whom have been executed and the rest forced to convert or subjected to the most horrendous disabilities."[135] Starting in late 1979 the new government systematically targeted the leadership of the Baháʼí community by focusing on the Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) and Local Spiritual Assemblies (LSAs); prominent members of NSAs and LSAs were either killed or disappeared.[127] Like most conservative Muslims, Khomeini believed them to be apostates, for example issuing a fatwa stating:

It is not acceptable that a tributary [non-Muslim who pays tribute] changes his religion to another religion not recognized by the followers of the previous religion. For example, from the Jews who become Baháʼís nothing is accepted except Islam or execution.[136]

and emphasized that the Baháʼís would not receive any religious rights, since he believed that the Baháʼís were a political rather than religious movement.[137][138]

the Baháʼís are not a sect but a party, which was previously supported by Britain and now the United States. The Baháʼís are also spies just like the Tudeh [Communist Party].[139]

This is all despite the fact that conversion from Judaism and Zoroastrianism in Iran is well documented since the 1850s – indeed such a change of status removing legal and social protections.[140][141][142][143][144]

Allegations of Baháʼí involvement with other powers have long been repeated in many venues including denunciations from the president.[63][145]

During the drafting of the new constitution, the wording intentionally excluded the Baháʼís from protection as a religious minority.[146] More recently, documentation has been provided that shows governmental intent to destroy the Baháʼí community. The government has intensified propaganda and hate speech against Baháʼís through the Iranian media; Baháʼís are often attacked and dehumanized on political, religious, and social grounds to separate Baháʼís from the rest of society.[147] According to Eliz Sanasarian "Of all non-Muslim religious minorities the persecution of the Bahais [sic] has been the most widespread, systematic, and uninterrupted.… In contrast to other non-Muslim minorities, the Bahais [sic] have been spread throughout the country in villages, small towns, and various cities, fueling the paranoia of the prejudiced."[63]

Since the 1979 revolution, the authorities have destroyed most or all of the Baháʼí holy places in Iran, including the House of the Bab in Shiraz, a house in Tehran where Bahá'u'lláh was brought up, and other sites connected to aspects of Babi and Baháʼí history. These demolitions have sometimes been followed by the construction of mosques in a deliberate act of triumphalism. Many or all of the Baháʼí cemeteries in Iran have been demolished and corpses exhumed. Indeed, several agencies and experts and journals have published concerns about viewing the developments as a case of genocide: Roméo Dallaire,[148][149] Genocide Watch,[150] Sentinel Project for Genocide Prevention,[151] War Crimes, Genocide, & Crimes against Humanity[116] and the Journal of Genocide Research.[152]

Religious freedom

Iran is an Islamic republic. Its constitution mandates that the official religion is Islam (see: Islam in Iran), specifically the Twelver Ja'fari school of Islam, with other Islamic schools being accorded full respect. Followers of all Islamic schools (excluding Ahmadiyya) are free to act in accordance with their own jurisprudence in performing their religious rites. The constitution recognizes Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians as religious minorities.

While several religious minorities lack equal rights with Muslims, complaints about religious freedom largely revolve around the persecution of the Baháʼí Faith, the country's largest religious minority, which faces active persecution.[128] During 2005, several important Baháʼí cemeteries and holy places have been demolished, and there were reports of imprisonment, harassment, intimidation, discrimination, and murder based on religious beliefs.[153]

Hudud statutes grant different punishments to Muslims and non-Muslims for the same crime. In the case of adultery, for example, a Muslim man who is convicted of committing adultery with a Muslim woman receives 100 lashes; the sentence for a non-Muslim man convicted of adultery with a Muslim woman is death.[154] In 2004, inequality of "blood money" (diya) was eliminated, and the amount paid by a perpetrator for the death or wounding a Christian, Jew, or Zoroastrian man, was made the same as that for a Muslim. However, in 2009, the International Religious Freedom Report reported that Baháʼís were not included in the provision and their blood is considered Mobah, (i.e. it can be spilled with impunity).[91]

Conversion from Islam to another religion (apostasy), is prohibited and may be punishable by death.[155] Article 23 of the constitution states, "the investigation of individuals' beliefs is forbidden, and no one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief." But another article, 167, gives judges the discretion "to deliver his judgment on the basis of authoritative Islamic sources and authentic fatwa (rulings issued by qualified clerical jurists)." The founder of the Islamic Republic, Islamic cleric Ruhollah Khomeini, who was a grand Ayatollah, ruled "that the penalty for conversion from Islam, or apostasy, is death."[156]

At least two Iranians – Hashem Aghajari and Hassan Yousefi Eshkevari – have been arrested and charged with apostasy (though not executed), not for converting to another faith but for statements and/or activities deemed by courts of the Islamic Republic to be in violation of Islam, and that appear to outsiders to be Islamic reformist political expression.[157] Hashem Aghajari, was found guilty of apostasy for a speech urging Iranians to "not blindly follow" Islamic clerics;[158] [160] Hassan Youssefi Eshkevari was charged with apostasy for attending the 'Iran After the Elections' Conference in Berlin Germany which was disrupted by anti-government demonstrators.[161] [165]

On 16 November 2018, two jailed Sufi Dervishes started a hunger strike demanding the information of whereabouts of their eight friends.[166]

Late November, 2018 prison warden Qarchak women prison in Varamin, near the capital Tehran attacked and bit three Dervish religious minority prisoners when they demanded their confiscated belongings back.[167]

For the year 2022, the Human Rights Activists in Iran Annual Report listed 199 cases involving religious rights, including 140 arrests, 94 cases of police home raids, 2 cases of demolition of religious sites, 39 cases of imprisonment, 51 issuances of travel bans (which violate of freedom of movement,) and 11 cases of individuals brought to trial for their religious beliefs. Almost two thirds (64.63%) of the cases involved the violation of the rights of Baha’is, while 20.84% involved the rights of Christians, 8.84% Yarsanis, 4.63% Sunnis, and 0.42% Dervishes.[168]

In 2023, the country was scored zero out of 4 for religious freedom by Freedom House,[169] and in that same year, ranked as the 8th most difficult place in the world to be a Christian by Open Doors.[170]

Irreligion in Iran

Non-religious Iranians are officially unrecognized by the Iranian government, this leaves the true representation of the religious split in Iran unknown as all non-religious, spiritual, atheist, agnostic and converts away from Islam are likely to be included within the government statistic of the 99% Muslim majority.[43]

According to Moaddel and Azadarmaki (2003), fewer than 5% of Iranians do not believe in God.[171] A 2009 Gallup poll showed that 83% of Iranians said religion is an important part of their daily life.[172] The 2020 online survey conducted by GAMAAN mentioned above, found a higher number of Iranians surveyed self-identify as atheists - 8.8%.[113]

According to a 2008 BBC report Zohreh Soleimani, was quoted saying, Iran has "the lowest mosque attendance of any Islamic country,"[173] and according to the Economist magazine in 2003, some Iranian clergy have complained that more than 70% of the population do not perform their daily prayers and that less than 2% attend Friday mosques.[174][175] Similarly, according to Pooyan Tamimi Arab and Ammar Maleki of GAMAAN detailing their survey results in the Conversation, over 60% of Iranians said they "did not perform the obligatory Muslim daily prayers", synchronous with "a 2020 state-backed poll" in Tehran in which "60% reported not observing" Ramadan fasting (the majority due to being “sick”).[176][177] said they always prayed and observed the fast during Ramadan (the majority due to being “sick”). Arab and Maleki contrast this with, "a comprehensive survey" conducted two years before the Islamic Revolution, where "over 80% said they always prayed and observed" Ramadan.[178]

However, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2018 said, 78% of Iranians believe religion to be very important in their lives. The same study also found that 38% of Iranians attend worship services weekly.[110] While another 2019 Pew Research Center, survey said 87% of Iranians pray on a daily basis, which was the second-highest percentage in Asia-Pacific, after Afghanistan (96%) and ahead of Indonesia (84%).[111]

While according to the World Values Survey a survey was conducted in 2020 which stated 70.5% Iranians considered religion important in their lives while 22% said it was somewhat important while 4.1% said religion wasn't important in their lives. When asked how often do they pray 63.7% said they prayed several times a day while 10% said they pray once a day while 7.2% said they pray several times a week while 6.6% said they only when attending religious events while 3.8% said only during holy days while 0.7% said once a year while 2.5% said less often while 5.4% said they never pray.[179]

The irreligiosity figures in the diaspora are higher, notably among Iranian-Americans.[180][181]

See also

- Iranian religions

- Freedom of religion in Iran

- Human rights in Iran

- Human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Islam in Iran

- Christianity in Iran

- Sikhism in Iran

- History of the Jews in Iran

- Persian Jews

- Hinduism in Iran

- Buddhism in Iran

- Zoroastrians in Iran

- Religion and culture in ancient Iran

- Religion of Iranian-Americans

- Irreligion in Iran

- Mardavij, a Persian Zoroastrian commander who unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Arab Muslim rule in Iran

- Shia clergy

References

Notes

- readers should know that specific regions would be ruled by various dynasties so many of the dynasties of Iran have overlapping dates as they co-existed in various neighboring regions as part of Iran.

- The survey was based on 50,000 respondents with 90% of those surveyed living in Iran. The survey was conducted in June 2020 for 15 days from June 17th to July 1st in 2020 and reflects the views of the educated people of Iran over the age of 19 (equivalent to 85% of Adults in Iran) and can be generalized to apply to this entire demographic. It has a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error.[112][113] According to its website, GAMAAN, the producers of the poll, aim "to extract (real) opinions of Iranians about sensitive issues and questions that cannot be freely answered under the existing situation in Iran by using innovative approaches and utilizing digital tools."[114]

Citations

- Fensham, F. Charles, "The books of Ezra and Nehemiah" (Eerdmans, 1982) p. 1

- "Iran", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 2023-05-02, retrieved 2023-05-10

- "WVS Database".

- "IRANIANS' ATTITUDES TOWARD RELIGION: A 2020 SURVEY REPORT". گَمان - گروه مطالعات افکارسنجی ایرانیان (in Persian). 2020-09-09. Retrieved 2022-11-28.

- Colin Brock, Lila Zia Levers. Aspects of Education in the Middle East and Africa Symposium Books Ltd, 7 mei 2007 ISBN 1873927215 p. 99

- "Jewish Population of the World". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- US State Dept 2022 report

- Kavian Milani (2012). "Bahaʼi (sic) Discourses on the Constitutional Revolution". In Dominic Parviz Brookshaw, Seena B. Fazel (ed.). The Bahaʼis (sic) of Iran: Socio-Historical Studies. Routledge. ISBN 9781134250004.

- United Nations (2005-11-02) Human rights questions: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Archived 2006-11-09 at the Wayback Machine General Assembly, Sixtieth session, Third Committee. A/C.3/60/L.45

- Akhavi, Shahrough (1980). Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran: clergy-state relations in the Pahlavi period. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-87395-408-4.

- Tavakoli-Targhi, Mohamed (2001). "Anti-Baháʼísm and Islamism in Iran, 1941–1955". Iran-Nameh. 19 (1): 79–124.

- Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: Foreign Affairs Committee (23 February 2006). Human Rights Annual Report 2005: First Report of Session 2005–06; Report, Together with Formal Minutes, Oral and Written Evidence. The Stationery Office. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-215-02759-7.

- Gorder, Christian (2010). Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-Muslims in Iran. Lexington Books. p. 22.

- "AFP: Iran young, urbanised and educated: Census". Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- R. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern TimesSUNY Press, 1998 ISBN 9780791436110 p. 37

- "Mani (Iranian prophet)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- "Manichaeism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Manichaeism". New Advent Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Reeves, John (2010). Prolegomena to a History of Islamic Manichaeism. London: Equinox Pub. p. 9. ISBN 9781904768524.

- Reeves, John (2010). Prolegomena to a History of Islamic Manichaeism. London: Equinox Pub. p. 10. ISBN 9781904768524.

- Reeves, John (2010). Prolegomena to a History of Islamic Manichaeism. London: Equinox Pub. p. 11. ISBN 9781904768524.

- Reeves, John (2010). Prolegomena to a History of Islamic Manichaeism. London: Equinox Pub. p. 7. ISBN 9781904768524.

- "COSMOGONY AND COSMOLOGY iii. In Manicheism". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

[I]n Manicheism the world was a prison for demons...

- Article by Sayyid 'Ali ibn 'Ali Al-Zaidi, A short History of the Yemenite Shiites (2005) Referencing: Iranian Influence on Moslem Literature

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005). The adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim traveler of the fourteenth century. University of California Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-520-24385-9.

- The Origins of the Sunni/Shia split in Islam Archived 2007-01-26 at the Wayback Machine by Hussein Abdulwaheed Amin, Editor of IslamForToday.com

- Curtis, Glenn E.; Hooglund, Eric J., eds. (2008). Iran: a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 119, 129–130. ISBN 978-0-8444-1187-3. OCLC 213407459.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services

- Four Centuries of Influence of Iraqi Shiism on Pre-Safavid Iran

- Andrew J. Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, I. B. Tauris (March 30, 2006)

- during Safavids era By Ehasan Yarshater, Encyclopedia Iranica

- Molach, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, 2005, p. 168

- Iran Archived 2013-08-13 at the Wayback Machine Janet Afary, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, 2005, p. 170

- Bayat, Mangol (1991). Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1909. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-19-506822-X.

- "Barack Obama's Cairo speech". London: Guardian.co.uk. 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis (2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today",The FASEB Journal 20, pp. 1581–86.

- Kühnel E., in Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesell, Vol. CVI (1956)

- Istanbul to host Ibn Sina Int'l Symposium, Retrieved on: December 17, 2008.

- Rumi Yoga

- Life of Rumi

- US Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2007). "International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Iran". US State Department. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- Mamouri, Ali (December 1, 2013). "Iranian government builds bridges to Sunni minority". Al-Monitor. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran, Part 3, Volume 7. p. 27. ISBN 9783406093975.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Van Donzel, E. J. (January 1994). Islamic Desk Reference. p. 225. ISBN 9004097384.

laristan sunni fars.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Matthee, Rudi (2012). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. p. 174. ISBN 9781845117450.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran, Part 3, Volume 7. pp. 27–29. ISBN 9783406093975.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Sunnis on the rise in Iran | IISS Voices". Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- "روش مقابله با افزايش جمعيت وهابيت در ايران". مؤسسه تحقیقاتی حضرت ولی عصر - عج (in Persian). Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (3 October 2013). "The Rise of Persian Salafism". Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Christian Solidarity Worldwide website, article dated July 12, 2023

- "Fact Check: Do Sunnis Have 'Enough Freedom' in Iran?". IranWire. 15 February 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Éric Geoffroy, Roger Gaetani, Introduction to Sufism: The Inner Path of Islam, World Wisdom, Inc, 2010. (p. 26)

- Matthijs van den Bos, Mystic regimes: Sufism and the state in Iran, from the late Qajar era to the Islamic Republic, Brill, 2002.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1987). The Devil: perceptions of evil from antiquity to primitive Christianity. Cornell University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8014-9409-3.

- Historical Churches in Iran Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Iran Chamber Society.

- "In Iran, 'crackdown' on Christians worsens". Christian Examiner. Washington D.C. April 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- Price, Massoume (December 2002). "History of Christians and Christianity in Iran". Christianity in Iran. FarsiNet Inc. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "In Iran, 'crackdown' on Christians worsens". Christian Examiner. Washington D.C. April 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Country Information and Guidance "Christians and Christian Converts, Iran" 19 March 2015. p. 9

- Price, Massoume (December 2002). "History of Christians and Christianity in Iran". Christianity in Iran. FarsiNet Inc. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious minorities in Iran. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53, 80. ISBN 978-0-521-77073-6.

- "Deputy culture min. meets Armenian Archbishop". 29 December 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "انتقال مقر جهاني آشوريان به ايران". Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- "ASSYRIANS IN IRAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- Curtis & Hooglund (2008), p. 295.

- BetBasoo, Peter (1 April 2007). "Brief History of Assyrians". Assyrian International News Agency. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Spellman, Kathryn (2004). Religion and nation: Iranian local and transnational networks in Britain. Berghahn Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-57181-576-7.

- Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 11: 8. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- 2011 General Census Selected Results (PDF), Statistical Center of Iran, 2012, p. 26, ISBN 978-964-365-827-4

- "Evangelical Growth - Operation World". Operation World. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Human Rights Watch Religious minorities

- "Iran is number 9 on the World Watch List".

- De Blois, François (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0952. Van Bladel, Kevin (2017). From Sasanian Mandaeans to Ṣābians of the Marshes. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004339460. ISBN 978-90-04-33943-9. p. 5.

- Contrera, Russell. "Saving the people, killing the faith – Holland, MI". The Holland Sentinel. Retrieved 2015-03-07.

- "Iran Mandaeans in exile following persecution". Alarabiya.net. 2011-12-06. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- "Ancient sect fights to stay alive in U.S. - US news – Faith – NBC News". NBC News. 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Elahi, Bahram (1987). The path of perfection, the spiritual teachings of Master Nur Ali Elahi. ISBN 0-7126-0200-3.

- Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2004) p. 82

- Edmonds, Cecil. Kurds, Turks, and Arabs: politics, travel, and research in north-eastern Iraq, 1919-1925. Oxford University Press, 1957.

- "Religion: Cult of Angels". Encyclopaedia Kurdistanica. Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- "Yazdanism". Encyclopaedia of the Orient. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-25.

- Principle Beliefs and Convictions

- IRAN: Life of Jews Living in Iran

- "Iran's proud but discreet Jews". BBC News. 2006-09-22. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- "Iran Jewish leader calls recent mass aliyah 'misinformation' bid".

- "Iran Jewish MP criticizes 'anti-human' Israel acts". Ynet. Reuters. 2008-05-07. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- Congress, World Jewish. "World Jewish Congress". www.worldjewishcongress.org. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- "International - Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 1999-11-09.

- U.S. State Department (2009-10-26). "Iran – International Religious Freedom Report 2009". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- Hennessy-Fiske, Molly; Abdollah, Tami (2008-09-15). "Community torn by tragedy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Yegar, M (1993). "Jews of Iran" (PDF). The Scribe (58): 2.. In recent years, Persian Jews have been well-assimilated into the Israeli population, so that more accurate data is hard to obtain.

- Willemen, Charles; Dessein, Bart; Cox, Collett; Gonda, Jan; Bronkhorst, Johannes; Spuler, Bertold; Altenmüller, Hartwig (1998), Handbuch der Orientalistik: Sarvāstivāda Buddhist Scholasticism, Brill, pp. 128–130, ISBN 978-90-04-10231-6

- Ghosh, Bobby (14 December 2015). "Iran's Sikhs get a better deal than many other minorities". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- Ghosh, Bobby (14 December 2015). "Iran's Sikhs get a better deal than many other minorities". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "Gurudwaras in Iran - World Gurudwaras". Gateway to Sikhism Foundation. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- National Population and Housing Census 2011 (1390): Selected Findings (PDF). The President's Office Deputy of Strategic Planning and Control. Statistical Center of Iran. 2011. p. 8, table 3, graph 3. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "آیا آتئیسم در ایران در حال گسترش است؟". BBC News فارسی.

- Maleki, Ammar; Arab, Pooyan Tamimi. "Iran's secular shift: new survey reveals huge changes in religious beliefs". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- "Iranians have lost their faith according to survey". Iran International. 2020-08-25. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- "A secular Iran? Study links political discontent with religious decline". TRT. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Survey of 50,000 Iranians Finds Almost Half Are No Longer Religious". KAYHAN LIFE. 2020-11-05. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- Trilling, David (17 January 2017). "Polling Iran: What do Iranians think?". Journalist's Resource. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- "2011 Iranian Population and Housing Census" (PDF).

- International Crisis Group. The Shiite Question in Saudi Arabia, Middle East Report No. 45, 19 September 2005 Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Iraq's unique place in the Sunni-Shia divide". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- "Religions in Iran | PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- "Religious commitment by country and age". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- Jeff Diamant (1 May 2019), "With high levels of prayer, U.S. is an outlier among wealthy nations", Pew Research Center. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Iranians have lost their faith according to survey". Iran International. 25 Aug 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "گزارش نظرسنجی درباره نگرش ایرانیان به دین". گَمان - گروه مطالعات افکارسنجی ایرانیان (in Persian). 2020-08-23. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- GAMAAN in English

- Federation Internationale des Ligues des Droits de L'Homme (August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in IRAN" (PDF). fidh.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- Affolter, Friedrich W. (January 2005). "The Specter of Ideological Genocide: The Baháʼí of Iran" (PDF). War Crimes, Genocide, & Crimes Against Humanity. Criminal Justice Program of Penn State Altoona. 1 (1): 75–114. ISSN 1551-322X. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Halm, H. "AHL-E ḤAQQ". Iranica.

- Wright, Robin (2000). "6: The Islamic Landscape". The Last Great Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 207. ISBN 0-375-40639-5. OCLC 1035881962. Retrieved 2020-10-20 – via Internet Archive.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–84. ISBN 0-521-77073-4.

- Saeid Jafari, "Zoroastrian takes center stage on Iran's political scene", Al-Monitor, 2 November 2017

- IRNA, "Iranian parliament debating bill on religious minorities", The Iran Projet, 29 November 2017

- Wright, Robin (2000). "6: The Islamic Landscape". The Last Great Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 210. ISBN 0-375-40639-5. OCLC 1035881962. Retrieved 2020-10-20 – via Internet Archive.

- Wright, Robin (2000). "6: The Islamic Landscape". The Last Great Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 216. ISBN 0-375-40639-5. OCLC 1035881962. Retrieved 2020-10-20 – via Internet Archive.

- "Jewish woman brutally murdered in Iran over property dispute". The Times of Israel. November 28, 2012. Retrieved Nov 3, 2014.

A government census published earlier this year indicated there were a mere 8,756 Jews left in Iran.

- Amnesty International (October 1996). "Dhabihullah Mahrami: Prisoner of Conscience". AI INDEX: MDE 13/34/96. Archived from the original on 2003-02-23. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- EU. 2004. (2004-09-13). EU Annual Report on Human Rights (PDF). Belgium: European Communities. ISBN 92-824-3078-2. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2007). "A Faith Denied: The Persecution of the Baháʼís of Iran" (PDF). Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- International Federation for Human Rights (2003-08-01). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Amir Kabir, Mirza Taqi Khan". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 38. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- de Vries, Jelle (2002). The Babi Question You Mentioned--: The Origins of the Baha'i Community of the Netherlands, 1844–1962. Peeters Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-90-429-1109-3.

- Fischer, Michael; Abedi, Mehdi (1990). Debating Muslims. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 48–54, 222–250. ISBN 0-299-12434-7.

- Taheri, Amir, The Spirit of Allah, (1985), pp. 189–90

- Akhavi, Shahrough (1980). Religion and politics in contemporary Iran: clergy-state relations in the Pahlavī period. SUNY Press. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-0-87395-408-2.

- Samii, Bill (13 September 2004). "Iran Report: September 13, 2004". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Inc. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- Turban for the Crown : The Islamic Revolution in Iran, by Said Amir Arjomand, Oxford University Press, 1988, p.169

- from Poll Tax, 8. Tributary conditions, (13), Tahrir al-Vasileh, volume 2, pp. 497–507, Quoted in A Clarification of Questions : An Unabridged Translation of Resaleh Towzih al-Masael by Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini, Westview Press/ Boulder and London, c1984, p.432

- Cockroft, James (1979-02-23). "Iran's Khomeini". Seven Days. III (1): 17–24.

- "U.S. Jews Hold Talks With Khomeini Aide on Outlook for Rights". The New York Times. 1979-02-13.

- source: Kayhan International, May 30, 1983; see also Firuz Kazemzadeh, `The Terror Facing the Baha'is` New York Review of Books, 1982, 29 (8): 43–44.

- Maneck (née Stiles), Susan (1984). "Early Zoroastrian Conversions to the Baháʼí Faith in Yazd, Iran". In Cole, Juan Ricardo; Momen, Moojan (eds.). Studies in Bábí and Baháʼí history. Vol. 2 of Studies in Babi and Baháʼí History: From Iran East and West (illustrated ed.). Kalimat Press. pp. 67–93. ISBN 978-0-933770-40-9.

- Smith, Peter (2000). "Zoroastrianism". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 369. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Maneck, Susan (1990). "Conversion of Religious Minorities to the Baha'i Faith in Iran: Some Preliminary Observations". The Journal of Baháʼí Studies. Association for Baháʼí Studies North America. 3 (3). Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Sharon, Moshe (2011-01-13). "Jewish Conversion to the Bahā˒ī faith". Chair in Baha'i Studies Publications. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Amanat, Mehrdad (2011). Jewish Identities in Iran: Resistance and Conversion to Islam and the Baha'i Faith. I.B.Tauris. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-84511-891-4.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2008). "The Comparative Dimension of the Baha'i Case and Prospects for Change in the Future". In Brookshaw, Dominic P.; Fazel, Seena B. (eds.). The Baha'is of Iran: Socio-historical studies. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-203-00280-3.

- Afshari, Reza (2001). Human Rights in Iran: The Abuse of Cultural Relativism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8122-3605-7.

- The Sentinel Project (2009-05-19). "Preliminary Assessment: The Threat of Genocide to the Baháʼís of Iran" (PDF). The Sentinel Project. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Dallaire, Roméo (29 November 2011). "Baha'i People in Iran—Inquiry". Statements from Roméo Dallaire. The Liberal caucus in the Senate. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Dallaire, Roméo (16 June 2010). "Baha'i Community in Iran". Statements from Roméo Dallaire. The Liberal caucus in the Senate. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- "Genocide and politicide watch: Iran". Genocide Watch; The International Alliance to End Genocide. 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Seyfried, Rebeka (2012-03-21). "Progress report from Mercyhurst: Assessing the risk of genocide in Iran". Iranian Baha'is. The Sentinel Project for Genocide Prevention. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Momen, Moojan (June 2005). "The Babi (sic) and Baha'i (sic) community of Iran: a case of "suspended genocide"?" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. 7 (2): 221–241. doi:10.1080/14623520500127431. S2CID 56704626. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- U.S. Department of State (2005-09-15). "International Religious Freedom Report 2006 – Iran". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- hrw.org, Iran – THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK

- Global Legal Research Directorate Staff; Goitom, Hanibal (June 2014). "Laws Criminalizing Apostasy". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - hrw.org Iran – THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK Legislation Affecting Freedom of Religion

- 7 November 2002. Iranian academic sentenced to death

- hrw.org, November 9, 2002 Iran: Academic's Death Sentence Condemned

- "Iranian dissident spared death sentence". ALJAZEERA. 20 July 2004. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- His sentence was reduced to five years in prison in 2004, after domestic Iranian and international outcry)[159]

- Iran: Trial for Conference Attendees

- Iranian dissident cleric Eshkevari released after 4 years in jail Payvand, 6 February 2005

- "PEN, Hojjatoleslam Hasan Yousefi Eshkevari". PEN.

- "Apostasy in the Islamic Republic of Iran". Iran Press Watch.

- These charges were overturned but new charges of 'propaganda against the Islamic Republic', 'insulting top-rank officials', 'spreading lies', were filed against him at the Special Court for the Clergy, in 2002, for which he received a sentence of seven years' imprisonment on 17 October.[162] He served four years in prison before and after his conviction, being released on 6 February 2005.[163][164]

- Jailed Dervishes Start Dry Hunger Strike To Protest Unknown Conditions Of Eight Sufis

- Gonabadi Dervish Women Brutally Beaten Up In Qarchak Prison

- "Religious Rights". Annual Report 2022, (PDF). Fairfax, VA 22033, USA: Human Rights Activists in Iran. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-1-7370668-6-6. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Freedom House website, retrieved 2023-08-08

- Open Doors website, retrieved 2023-08-08

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-12. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "What Alabamians and Iranians Have in Common". Gallup.com. 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- children of the revolution

- Economist 16, January 2003

- Brian H. Hook. "Iran Should Reconcile With America". New York Times.

- "ispa polling [farsi language]". ispa.ir. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Pooyan Tamimi Arab and Ammar Maleki (September 10, 2020). "Iran's secular shift: new survey reveals huge changes in religious beliefs". The Conversation. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ALI ASSADI and MARCELLO L. VIDALE (January–June 1980). "Survey of Social Attitudes in Iran". International Review of Modern Sociology. 10 (1): 65–84. JSTOR 41420721. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- "WVS Database". www.worldvaluessurvey.org. Retrieved 2023-04-02.

- Public Opinion Survey of Iranian Americans. Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA)/Zogby, December 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- "Disparaging Islam and the Iranian-American Identity: To Snuggle or to Struggle". payvand.com. 21 September 2009.

Further reading

- Boroumand, Ladan (2020). "Iranians Turn Away from the Islamic Republic". Journal of Democracy. 31 (1): 169–181. doi:10.1353/jod.2020.0014.

- Tamadonfar, M., & Lewis, R. (2019, June 25). Religious Regulation in Iran. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Retrieved 20 Oct. 2023, from https://oxfordre-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-864.