Residential segregation in the United States

Residential segregation is the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods[1]—a form of segregation that "sorts population groups into various neighborhood contexts and shapes the living environment at the neighborhood level".[2] While it has traditionally been associated with racial segregation, it generally refers to the separation of populations based on some criteria (e.g. race, ethnicity, income/class).[3]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Racial/ethnic segregation |

|---|

|

|

While overt segregation is illegal in the United States, housing patterns show significant and persistent segregation along racial and class lines. The history of American social and public policies, like Jim Crow laws and the Federal Housing Administration's early redlining policies, set the tone for segregation in housing that has sustained consequences for present-day residential patterns.

Trends in residential segregation are attributed to discriminatory policies and practices, such as exclusionary zoning, location of public housing, redlining, disinvestment, and gentrification, as well as personal attitudes and preferences. Residential segregation produces negative socioeconomic outcomes for minority groups, influencing disparities in educational opportunity, access to health care and food, and employment.[4] Public policies for housing reform, like the Housing Choice Voucher program, attempt to promote integration and mitigate these negative effects, but with mixed results.[5]

History

In the early 1900s, U.S. cities were largely integrated, with working-class, typically immigrant, White families living in the same neighborhoods as working-class Black families.[6] However, the early 1930s marked the beginning of discriminatory housing policies. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted New Deal reforms that involved segregating some of these integrated working-class neighborhoods. To combat a housing shortage due to the Great Depression, FDR started public housing projects for working-class families, all of which were segregated, and most of which were limited to White people.[6] World War II brought an influx of workers to cities looking for jobs, increasing the number of public housing projects. White projects tended to be built in already residential neighborhoods, while Black projects tended to be built on the outskirts of these areas, displacing Black families out of residential centers where they had previously lived.[6] In 1949, Congress passed the 1949 Housing Act, which explicitly stated that the government could fund segregated housing projects. Beginning in the 1940s, the Federal Housing Administration created programs that encouraged White families to move into suburban neighborhoods by providing affordable mortgages, with racially restrictive covenants barring Black families from buying houses in these White neighborhoods.[7] White families benefitted greatly from these programs, as it provided them with economic stability and accumulation of wealth due to increasing real estate values. As White families moved out of urban housing projects, previously White-only public housing projects allowed Black families to move in. Public housing became dominated by working-class Black families, who had limited access to employment and economic opportunities.[6] These discriminatory housing policies are responsible for the racial wealth gap and persistent residential segregation between White and Black households today: the average Black family makes about 60% of the average White family's income, while the median net worth of a Black family is 10% of a White family's net worth.[6]

Recent trends

The index of dissimilarity allows measurement of residential segregation using census data, with values ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates no segregation and 100 means complete segregation. It uses United States census data to analyze housing patterns based on five dimensions of segregation: evenness (how evenly the population is dispersed across an area), isolation (within an area), concentration (in densely packed neighborhoods), centralization (near metropolitan centers), and clustering (into contiguous ghettos).[8] Hypersegregation is high segregation across all dimensions.

Another tool used to measure residential segregation is the neighborhood sorting indices, showing income segregation between different levels of the income distribution.[9]

Racial

An analysis of historical U.S. Census data by Harvard and Duke scholars indicates that racial separation has diminished significantly since the 1960s. Published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, the report indicates that the dissimilarity index has declined in all 85 of the nation's largest cities. In all but one of the nation's 658 housing markets, the separation of black residents from other races is now lower than the national average in 1970. Segregation continued to drop in the last decade, with 522 out of 658 housing markets recording a decline.[10][11]

Despite recent trends, Black communities remain the most segregated racial group. The dissimilarity-index indices in 1980, 1990 and 2000 are 72.7, 67.8, and 64.0, respectively.[12] Black people are hypersegregated in most of the largest metropolitan areas across the U.S., including Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, DC.[8] For Hispanics, the second most segregated racial group, the indices from 1980, 1990 and 2000 are 50.2, 50.0, and 50.9, respectively.[12]

Hispanics are highly segregated in a number of cities, primarily in northern metropolitan areas.[8] Segregation for Asians and Pacific Islanders has been consistently low and stable on the Index of Dissimilarity over the decades. The indices from 1980, 1990 and 2000 are 40.5, 41.2 and 41.1, respectively.[12] Segregation for Native Americans and Alaska Natives has also been consistently the lowest of all groups and has seen a decline over the decades. The indices from 1980, 1990 and 2000 are 37.3, 36.8 and 33.3, respectively.[12]

Income

Analysis of patterns for income segregation come from the National Survey of America's Families, the Census and Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data. Both the index of dissimilarity and the neighborhood sorting indices show that income segregation grew between 1970 and 1990. In this period, the Index of Dissimilarity between the affluent and the poor increased from .29 to .43.[13]

Poor families are becoming more isolated. Whereas in 1970 only 14 percent of poor families lived in predominantly poor areas, this number increased to 28 percent in 1990 and continues to rise.[13] Most low-income people live in the suburbs or central cities. When looking at areas classified as "high-poverty" or "low-poverty" in 2000, about 14% of low-income families live in high-poverty areas and 35% live in low-poverty areas.[14]

Combined

More than half of all low-income working families are racial minorities.[14] Over 60% of all low-income families lived in majority white neighborhoods in 2000. However, this statistic describes the settlement patterns mainly of white low-income people. Black and Hispanic low-income families, the two most racially segregated groups, rarely live in predominantly white or majority-white neighborhoods. A very small portion of low-income white families lives in high-poverty areas. One in three black low-income families live in high-poverty areas while one of every five Hispanic low-income families lives in high-poverty areas.[14]

Housing demographics

Homeownership

National trends for homeownership show a general upward trend since the 1980s, with a 2010 rate of 66.9%. As of 2010, 71% of Whites were homeowners. The rates for Black, Hispanic, and all other racial groups remain consistently and significantly below the national average, with homeownership rates in 2010 of 45%, 48%, and 57%, respectively.[15] Looking at all homeowners in 2007, about 87% are White.[16] Low-income individuals are less likely to be homeowners than other income groups and pay a greater portion of their income on housing. Individuals living in poverty represent a very small portion of homeowners.[16]

Rental

Census information on renters shows significant disparity between the races for renters. Of all renters, about 71% are white, 21% are black, 18% are Hispanic and 7% are Asian.[16] Renters are generally less affluent than homeowners. From 1991 to 2005, the percentage of low-income renters increased significantly.[16]

Influences on segregation

Current trends in racial and income based residential segregation in the United States are attributed to several factors, including:

- Historical housing discrimination

- Exclusionary zoning practices

- Location of public housing

- Discriminatory homeownership practices

- Neighborhood disinvestment

- Gentrification

- Attitudes and preferences towards housing location

These factors impact both racial and class-based segregation differently.

Exclusionary zoning

Exclusionary zoning influences both racial and income-based segregation.

Racial zoning

Incidents of exclusionary zoning separating households by race appeared as early as the 1870s and 1880s, when municipalities in California adopted anti-Chinese policies. For example, an 1884 San Francisco ordinance regulated the operation of laundries, which were a source of employment and gathering places for Chinese immigrants. The ordinance withstood several legal challenges before the U.S. Supreme Court eventually struck it down because of its anti-Chinese motivations.

The prominent real estate developer J.C. Nichols was famous for creating master-planned communities with covenants that prohibited African Americans, Jews, and other races from owning his properties.

A decade later, the Supreme Court passage of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) established "separate but equal" zoning ordinances that specified exclusively black, white and mixed districts and legally established segregation in housing opportunities. Many large and mid-sized cities in the South and mid-South adopted racial zonings between 1910 and 1915. In Buchanan v. Warley (1917) the Supreme Court ruled that racial zoning was illegal but many local governments continued to enforce racial segregation with alternative land use designations.[17] Although there has been a supreme court passing in hopes to end racial disparities in residential zonings, it seems as though to date there is still evidence of racial disparities within residential zonings this is because of the "historically differing extent of political representation and advocacy between white and African American communities(Whittemore, 1). Zoning regulations presently isolate communities by wealth and income. Since a minority of low-income families genuinely have less money due to segregationist zoning regulations and other racially discriminatory arrangements, minorities are prohibited from the more significant parts of specific areas within cities in the south.[18] Many of these deeds and covenants remain active, and continue to influence settlement patterns.

Land-use zoning

Local jurisdictions that adopt land-use zoning regulations such as large-lot zoning, minimum house size requirements, and bans on secondary units make housing more expensive. As a result, this excludes lower income racial and ethnic minorities from certain neighborhoods.[17]

Location of public housing

The location of public housing developments influences both racial and income segregation patterns. Racial segregation in public housing programs occurs when high concentrations of a certain minority group occupy one specific public housing development. Income segregation occurs when high concentrations of public housing are located in one specific income area.

Racial segregation in public housing

Federal and local policies have historically racially segregated public housing.

Local jurisdictions determined whether to incorporate public housing into their locality and most had control over where low income housing sites were built. In many areas, the white majority would not allow public housing to be built in "their" neighborhoods unless it was reserved for poor whites. Black elected officials recognized the need for housing for their constituents, but felt that it would be politically unpopular to advocate for inclusionary housing.[19]

Of the 49 public housing units constructed before World War II, 43 projects supported by the Public Works Administration and 236 of 261 projects supported by the U.S. Housing Authority were segregated by race.[20] Anti-discrimination laws passed after World War II led to a reduction in racial segregation for a short period of time, but as income-ineligible tenants were removed from public housing, the proportion of black residents increased.[20] The remaining low-income white tenants were often elderly and moved to projects reserved specifically for seniors. Family public housing units then became dominated by racial minorities.[20]

Three of the more infamous minority concentrated public housing projects in America were Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and Cabrini-Green and Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago.

Income segregation in public housing

Determining if a disproportionate level of public housing exists in low-income neighborhoods is hard because defining low, moderate and high income geographic locations, and locating projects in these locations is difficult.[20] Assumptions affirming the density of public housing in low-income areas are supported by the fact that public housing units built between 1932 and 1963 were primarily located in slum areas and vacant industrial sites.[20] This trend continued between 1964 and 1992, when a high density of projects were located in old core cities of metropolitan areas that were considered low income.[20]

Redlining

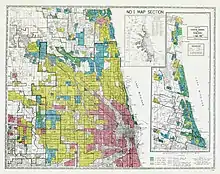

In 1933, the federally created Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps that coded areas as credit-worthy based on the race of their occupants and the age of the housing stock. These maps, adopted by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1944, established and sanctioned "redlining". Residents in predominately minority neighborhoods were unable to obtain long-term mortgages on their homes because banks would not authorize loans for the redlined areas. Unlike their white counterparts, many minorities were not able to receive financing to purchase the homes they lived in and did not have the means to move to more affluent areas where banks would authorize home loans.

Due to the early discriminatory practices of mortgage lending, the black population remains less suburbanized than whites. Blacks, and to a lesser extent, other ethnic minorities remain isolated in urban environments with lesser access to transportation, jobs, health care and many of the amenities that are available to suburban residents. Thirty-nine percent of blacks live in the suburbs, compared to 58 percent of Asians, 49 percent of Hispanics and 71 percent of non-Hispanic whites.[21] Further, post-World War II homebuilding in the suburbs benefitted whites, as housing prices tripled in the 1970s, enabling white homeowners to increase the equity of their homes. Because of this, blacks face higher costs of entry to the housing market, and those that are able to seek housing in the suburbs tend to live in lower-income, less desirable areas just outside the city limits.[21]

Steering

"The United States Supreme Court defines steering as a 'practice by which real estate brokers and agents preserve and encourage patterns of racial segregation in available housing by steering members of racial and ethnic groups to buildings occupied primarily by members of such racial and ethnic groups and away from buildings and neighborhoods inhabited primarily by members of other races or groups.'"[22] The theory supporting steering asserts that real estate agents steer people of color toward neighborhoods that are disproportionately black and/or Hispanic, while white homebuyers are directed to primarily white neighborhoods, continually reinforcing segregation. In some studies, real estate agents present fewer and more inferior options to black homeseekers than they do to whites with the same socioeconomic characteristics.[23]

Even though the Fair Housing Act made discrimination in housing illegal, there is a belief that steering is still common. For example, real estate agents will assume white homebuyer's initial requests are an accurate reflection of their preferences, while they second guess a minority homebuyer's request, and adjust it to their personal perceptions. Moreover, some real estate agents will acknowledge that their actions are prohibited by saying such things as:

- "'This area has a questionable ethnic mix, I could lose my license for saying this!'"[22]

- "'[The area] is different from here; its multicultural. ... I'm not allowed to steer you, but there are areas you wouldn't want to live in.'"[22]

A recent study of housing discrimination using matched pairs of home seekers who differed only in race to inquire about housing show that for those seeking rental units, blacks received unfavorable treatment 21.6 percent of the time, Hispanics 25.7 percent of the time, and Asians 21.5 percent of the time. Moreover, blacks interested in purchasing a home experienced discrimination 17 percent of the time, Hispanics 19.7 percent of the time and Asians 20.4 percent of the time.[22]

These conclusions are challenged because it is not clear what level of discrimination is necessary to make an impact of the housing market. There is also criticism of the methods used to determine discrimination and it is not clear if paired testing accurately reflects the conditions in which people are actually searching for housing.[24]

Real estate appraisals

Real estate appraisal is the subjective valuation of real estate properties based on factors like market value. Studies have found that appraisers tend to value properties owned by minorities lower than properties owned by white people, known as an appraisal gap.[25] This is due to appraiser's biased perceptions of neighborhoods based on the racial demographics.[26] Lower property appraisals consequently lead to higher rates of mortgage application rejections[27] and keep property values in minority neighborhoods and of minority families in primarily white neighborhoods down.[28]

Neighborhood disinvestment

Neighborhood disinvestment occurs when a city systematically limits funding for public resources in typically urban neighborhoods, which tend to fall along racial/ethnic lines. This limits public goods available to these communities, such as funding for public education, and leads to continued undervaluation of property values.[29] Re-investment in disinvested neighborhoods, rather than leading to improved property values and living conditions for minority residents, can lead to gentrification, as covered in the following section.

Gentrification

Gentrification is another form of class- and race-based residential segregation.[30] Gentrification is defined as displacement of lower-income, frequently minority residents by higher-income, typically White residents and businesses in urban neighborhoods.[31] Gentrification in the U.S. has involved significant re-investment in previously disinvested neighborhoods and destruction of public affordable housing projects, targeting projects with majority Black residents, and resulting in the displacement of hundreds of thousands of primarily Black, low-income families since the 1980s.[32] Critical race theory is used to examine the intersection of race and class in demographic changes in the U.S.[33]

Attitudes and preferences

"White flight" is one theory supporting the idea that biases formed based on racial concentrations of neighborhoods influence residential choice. White flight is the phenomenon of white families moving out of neighborhoods as they become racially integrated, perpetuating patterns of residential segregation. The racial white flight hypothesis states that this phenomenon is racially motivated, rather than motivated by alternate socioeconomic concerns. Studies have shown that white flight is most prominent in middle-class, suburban neighborhoods.[34]

Residential preferences of blacks are categorized by social-psychological and socioeconomic demographic characteristics. The theory behind social psychological residential preference is that segregation is a result of blacks choosing to live around other blacks because of cultural similarities, maintaining a sense of racial pride, or a desire to avoid living near another group because of fear of racial hostility. Other theories suggest demographic and socioeconomic factors such as age, gender and social class background influence residential choice. Empirical evidence to explain these assumptions is generally limited.[35]

One empirical study completed in 2002 analyzed survey data from a random sample of blacks from Atlanta, Boston, Detroit and Los Angeles.[35] The results of this study found that the housing preferences of blacks are largely attributed to discrimination and white hostility, not a desire to live with a similar racial group.[35] In other words, the study found that blacks choose specific residences because they are afraid of hostility from whites.

Critics of these theories suggest that the survey questions used in the research design for these studies imply that race is a greater factor in residential choice than access to schools, transportation, and jobs. They also suggest that surveys fail to consider the market influences on housing including availability and demand.[24]

Existing data on the role of immigration on residential segregation trends in the US suggest that foreign-born Hispanics, Asians and blacks often have higher rates of segregation than do native-born individuals from these groups. Segregation of immigrants is associated with their low-income status, language barriers, and support networks in these enclaves. Research on assimilation shows that while new immigrants settle in homogenous ethnic communities, segregation of immigrants declines as they gain socioeconomic status and move away from these communities, integrating with the native-born.[36]

Consequences of segregation

Location of housing is a determinant of a person's access to the job market, transportation, education, healthcare, and safety. People residing in neighborhoods with high concentrations of low-income and minority households experience higher mortality risks, poor health services, high rates of teenage pregnancy, and high crime rates.[37] These neighborhoods also experience higher rates of unemployment, and lack of access to job networks and transportation, which prevents households from fully gaining and accessing employment opportunities. The result of isolation and segregation of minority and economically disadvantaged communities is increased racial and income inequality, which in turn reinforces segregation.[21] A 2015 Measure of America report on disconnected youth found that black youth in highly segregated metro areas are more likely to be disconnected from work and school.[38] In 2014, the Child Opportunity Index measures very high to very low opportunity comparing race and ethnicity in the 100 largest US metropolitan areas in the US to compare inequalities and residential segregation.[39]

Education

Residentially segregated neighborhoods, in combination with school zone gerrymandering, leads to racial/ethnic segregation in schools. Studies have found that schools tend to be equally or more segregated than their surrounding neighborhoods, further exacerbating patterns of residential segregation and racial inequality.[40] Schools with majority-minority populations are consistently underfunded; school districts with high populations of Hispanic and Black students receive on average $5000 less per student than school districts with majority White students.[41] Limited funding results in limited resources and academic opportunities for students. Studies have demonstrated a link between school spending and student outcomes, further exacerbating racial inequality.[42]

Healthcare

Access to healthcare varies across neighborhoods. A 2012 study looked at the access to primary care physicians; researchers Gaskin et al. found that zip codes with majority Black residents were much more likely to have a shortage of primary care physicians than neighborhoods with any other racial demographic makeup.[43] Additionally, residentially segregated minority groups suffer disparate health consequences. For example, a 2009 study by researcher Walton found that residential segregation paired with poverty led to lower birth weights in Black communities.[44]

Food deserts

A food desert is an area that has a lack of access to grocery stores and fresh, unprocessed foods. Food deserts tend to be neighborhoods with predominantly minority residents. Studies have shown that predominantly White areas and racially mixed areas have much more consistent access to supermarkets and fresh fruits and vegetables, while many predominantly Black neighborhoods have no grocery stores and limited access to fresh foods.[45] Residents in more segregated areas have less variation in the food available to them, which is mostly fast food and processed food from convenience stores, and have to travel farther distances to access healthy food options.[46] A lack of a nutritional diet consisting of fresh fruits and vegetables can lead to increased health risks, such as increased risk of disease.

Urban heat islands

Urban heat islands are areas of cities that have much higher temperatures than other neighborhoods due to a high amount of concrete and a lack of trees and green spaces. In a 2013 study of the relationship between urban heat islands and residentially segregated neighborhoods, Jesdale et al. found that Black communities were 52% more likely than White communities to live in areas with high heat risk.[47] Additionally, urban heat islands closely align with redlined neighborhoods and can reach temperatures up to 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than white neighborhoods.[48] Extreme heat events are the leading cause of climate-related deaths, and are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change.[49]

Employment

In addition to factors like socioeconomic status and distance from job centers, residential segregation has a negative impact on employment opportunities for Black people, while not impacting White people's employment opportunities. A 2010 study found that residential segregation could account for the employment gap along racial lines. Additionally, researcher VonLockette points out that a majority of low-income White people live in low-poverty neighborhoods, while a majority of low-income Hispanic and Black people live in high-poverty neighborhoods, creating a disparity in access to neighborhood resources, including networks for employment access, due to class disparities compounded with racial disparities.[50]

Social policies and initiatives

In 1948, the Supreme Court outlawed the enforcement of racial covenants with Shelley v. Kraemer, and two decades later the Fair Housing Act of 1968 incorporated legislation that prohibited discrimination in private and publicly assisted housing. The 1975 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act limited mortgage lenders' ability to provide discretion in issuing loans and requiring that lenders provide full disclosure of where and to whom they were providing housing loans, in addition to requiring that they provide loans for all areas where they do business.[21] The passage of fair housing laws provided an opportunity for legal recourse against local and federal agencies that segregated residents and prohibited integrated communities.

Despite these laws, residential segregation still persists. More strict enforcement of these laws could prevent discriminatory lending practices and racial steering.[51] Moreover, educating property owners, real estate agents, and minorities about the Fair Housing Act and housing discrimination could help reduce segregation.

The class action lawsuit Hills v. Dorothy Gautreaux alleged that the development of Chicago Housing Authority's (CHA) public housing units in areas of high concentration of poor minorities violated federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) policies and the Fair Housing Act. The 1976 court decision resulted in HUD and CHA agreeing to mediate segregation imposed on Chicago public housing residents by providing Section 8 voucher assistance to more than 7,000 black families. The Section 8 assistance provided blacks the opportunity to move out of racially segregated areas and into mixed neighborhoods. Policymakers theorized that housing mobility would provide residents with access to "social capital", including ties to informal job networks. About seventy-five percent of the Gautreaux households were required to move to predominately white suburban neighborhoods while the remaining 25% were allowed to move to urban areas with 30% or more black residents.[52]

Social scientists researched the impacts of mobility on Gautreaux participants and found that children with access to better performing neighborhoods experienced improvements in educational performance, were less likely to drop out of school and more likely to take college preparation classes than their peers who had moved to more segregated areas of Chicago.[52]

Congress authorized the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration (MTO) in 1993. MTO shares a similar design to Gautreaux. However, the program focuses on economic desegregation instead of racial desegregation. As of 2005, MTO has allocated nearly $80 million in federal and philanthropic funding to disperse and de-concentrate low-income neighborhoods, track the short and long-term effects of MTO program participants, and determine if small low-income de-concentration programs can be expanded to a national scale.[52] An early randomized, controlled study on differential mental health effects indicates the pairing of portability housing vouchers to promote quality housing and lives with other programs, such as tobacco use of youth.[53]

In addition to the MTO program, the federal government provided funding to demolish 100,000 of the nation's worst public housing units and rebuild the projects with mixed income communities. This program, known as HOPE VI, has received mixed results. Some of the rebuilt projects continue to struggle with gangs, crime, and drugs. Some tenants choose not to return to the locations after redevelopment. While it may be too soon to determine the overall effect of the HOPE VI program, the Bush administration recommended termination of the program in 2004.[52]

Inclusionary zoning practices refer to local planning ordinances that can increase the supply of affordable housing, reduce the cost of creating housing, and enforce regulations that improve the health, safety and quality of life for low income and minority households.[17]

Examples of residential segregation in U.S. cities

Residential segregation in Atlanta, GA

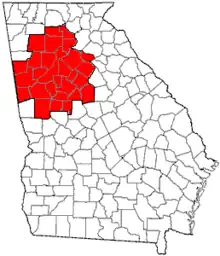

Within the Atlanta Metropolitan Area, residential segregation is highest among DeKalb and Fulton Counties, the two most urbanized counties in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area.[54] These counties consist of 70% of the black residents in Atlanta, meaning that a strong majority of Atlanta's black citizens are living in the city's most urbanized areas.[55] In addition, white families have been steadily moving to suburban areas around Atlanta since the 1980s,[56] leaving counties such as DeKalb and Fulton to consist of majority or nearly majority black residents, with 55.3% of residents in DeKalb County being black[57] and 44.5% of residents in Fulton County being black.[58] Furthermore, the suburban areas outside of Atlanta and Fulton and DeKalb county tend to be less racially segregated,[56] yet black residents in these suburbs, as well as in more urban areas, are still the most segregated of any race of residents in Atlanta.[55] According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the current state of residential segregation, largely by race, occurred due to housing development practices and city infrastructure changes during the 20th century.[59] In order to implement new housing programs and interstates throughout the 20th century, the City of Atlanta chose to remove many poor or low income neighborhoods.[59] The removal of these neighborhoods disproportionately affected black Atlanta citizens, and made housing more expensive and poverty more concentrated on the southern side of Atlanta, in counties such as DeKalb and Fulton.[54][59]

Effects of residential segregation on poverty in Atlanta

As more white residents moved to the suburbs throughout the 1980s, black residents remained in many of the same urban areas.[56] The migration of much of the middle class to the suburbs of Atlanta decreased poverty levels for black residents in Atlanta as a whole,[56] but it left residents at or near poverty exposed to much higher levels of poverty as the middle class migrated out and took resources with them.[56] Furthermore, moves made by black residents at or below the poverty level to escape impoverished neighborhoods within Atlanta were overshadowed by the same moves made by white residents, leaving mainly black residents exposed to poverty within metropolitan Atlanta after movements made by the middle class.[56] This shift in residence has disproportionately left black citizens in Atlanta exposed to poverty, with 80% of black children living in Atlanta being exposed to poverty.[59] Within these areas, which are largely in southern Atlanta in areas of DeKalb and Fulton County,[54] residents are having to spend 30% of their annual income on housing.[59]

Effects of residential segregation and consequential poverty on education

Research gathered from the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI) shows that in Georgia, schools with higher numbers of students living in poverty perform more poorly on standardized state exams and are given poorer scores from the Georgia Governor's Office of Student Achievement, with 99% of schools in extreme poverty and 79% of schools in high-poverty receiving grades of D or F from the Office of Student Achievement.[60] In addition, the GBPI found that in most of these struggling schools, students are primarily of racial minorities: In 98% of public schools in Georgia considered to be extremely impoverished, 75% or more of the students are black or Hispanic.[60] In Atlanta, students from northern counties are enrolled in pre-school in higher rates than in the southern counties (such as Fulton and DeKalb),[59] and 11 of the top 14 performing schools within the Atlanta Public School District were in Atlanta's northern counties.

Residential segregation in Detroit, MI

Detroit, MI is one of the most residentially segregated cities in the U.S. today, with an index of dissimilarity of 68.52,[61] as well as having one of the highest poverty rates of any large U.S. city (33.8% in 2007).[62] Detroit's demographic breakdown is 78.3% Black, 10.5% non-Hispanic White (96% of whom live in suburbs), 7.7% Hispanic, and less than 5% other racial groups.[63]

In the 1940s, 80% of property outside of the inner-city limits was controlled by racially restrictive covenants, barring Black families from buying homes in these neighborhoods. In the 1950s, landlords continued to refuse to rent to Black people, or charged them significantly higher rent than they charged white people. Additionally, Black families faced harassment and violence from White homeowners. In 1967, Black people rioted against police violence and housing/employment discrimination, known as the 1967 Detroit Riot; after Governor Romney called in the Michigan Army National Guard and President Johnson called in the U.S. Army, 43 people were killed and 1,189 were wounded. Residential segregation was exacerbated by a combination of White flight, redlining, and discriminatory real estate practices.[64] Residential segregation has had major consequences for poverty and health disparities; for example, a 2016 study in the Journal of Urban Health found significantly higher levels of childhood blood poisoning in Black children than White children in Detroit, and that a neighborhood's socioeconomic position was correlated with average blood lead levels in children.[65]

See also

References

- Massey, D. S.; Denton, N. A. (1988). "The Dimensions of Residential Segregation". Social Forces. 67 (2): 281–315. doi:10.1093/sf/67.2.281. JSTOR 2579183.

- Kawachi, Ichiro and Lisa F. Berkman. Neighborhoods and Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. page 265

- Eric M. Uslaner, "Producing and Consuming Trust". Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 115, No. 4 (Winter, 2000-2001), pp. 569-590

- Akbar, Prottoy; Li, Sijie; Shertzer, Allison; Walsh, Randall (2022). "Racial Segregation in Housing Markets and the Erosion of Black Wealth". The Review of Economics and Statistics: 1–45. doi:10.1162/rest_a_01276.

- Graves, Erin (2016-03-03). "Rooms for Improvement: A Qualitative Metasynthesis of the Housing Choice Voucher Program". Housing Policy Debate. 26 (2): 346–361. doi:10.1080/10511482.2015.1072573. hdl:10.1080/10511482.2015.1072573. ISSN 1051-1482. S2CID 55566185.

- "A history of residential segregation in the United States" (PDF). Institute for Research on Poverty.

- Boustan, Leah Platt (May 2013). Racial Residential Segregation in American Cities (PDF) (Report). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. w19045. doi:10.3386/w19045.

- Denton, N.A. (2006). "Segregation and discrimination in housing." In A Right to Housing: Foundation for a New Social Agenda, eds. Rachel G. Bratt, Michael E. Stone, and Chester Hartman, 61–81. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

- Watson, T. (2005). Metropolitan growth and neighborhood segregation by income. Seminar Paper, Department of Economics, Williams College. Retrieved: December 6, 2011 from: https://web.williams.edu/Economics/seminars/watson_brook_1105.pdf

- "End of the Segregated Century: Racial Separation in America's Neighborhoods, 1890–2010". Journalist's Resource. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- Edward Glaeser, Jacob Vigdor. "The End of the Segregated Century: Racial Separation in America's Neighborhoods, 1890–2010". Manhattan Institute, Number 66, January 2012

- Iceland, J., Weinberg, D.H., and Steinmetz, E. (2002). Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980–2000, U.S. Census Bureau, Series CENSR-3. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved: October 9, 2011 from https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/housing_patterns/pdftoc.html

- Massey, D. S.; Rothwell, J.; Domina, T. (2009). "The Changing Bases of Segregation in the United States". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 626 (1): 74–90. doi:10.1177/0002716209343558. JSTOR 40375925. PMC 3844132. PMID 24298193.

- Turner, M.A. and Fortuny, K. (2009). Residential Segregation and Low-Income Working Families. Urban Institute. Retrieved: October 12, 2011 from http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/411845_residential_segregation_liwf.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Housing Vacancies and Homeownership Annual Statistics: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved: November 19, 2011 from https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/hvs/annual10/ann10ind.html

- Schwartz, A.F. (2008). Housing Policy in the United States. New York: Routledge, 22.

- Pendall, R., Nelson, A., Dawkins, C., Knapp, G. (2005). Connecting smart growth, housing affordability, and Racial Equity. In The Geography of Opportunity, ed X. de Souza Briggs, 219-246. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

- Whittemore, Andrew H. (3 March 2020). "The Roots of Racial Disparities in Residential Zoning Practice: The Case of Henrico County, Virginia, 1978–2015". Housing Policy Debate. 30 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1080/10511482.2019.1657928. S2CID 211426053.

- Schwartz, A.F. (2008). Housing Policy in the United States. New York: Routledge, 132

- Coulibaly, M., Green, R.R., James, D. (1998) Segregation in Federally Subsidized Low-income Housing in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Denton, pp. 65-66

- The Poverty Race Research Action Council and The National Fair Housing Alliance. "Racial Segregation and Housing Discrimination in the United States," 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2011 from https://www.prrac.org/pdf/FinalCERDHousingDiscriminationReport.pdf

- Turner, M.A. and Ross, S.L. (2005). How racial discrimination affects the search for housing. In The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America, ed. Xavier de Souza Briggs, 81-100. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press

- von Hoffman, A., Beklsky, E. S., and Lee, K. "The Impact of Housing on Community: a Review of Scholarly Theories and Empirical Research," 2006. Joint Center for Housing Studies Harvard University. Retrieved October 8, 2011 from

- "Racial and Ethnic Valuation Gaps In Home Purchase Appraisals". Freddie Mac.

- Howell, Junia; Korver-Glenn, Elizabeth (2018-02-28). "Neighborhoods, Race, and the Twenty-first-century Housing Appraisal Industry". Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 4 (4): 473–490. doi:10.1177/2332649218755178. ISSN 2332-6492. S2CID 158568139.

- LaCour-Little, Michael; Green, Richard K. (1998). "Are Minorities or Minority Neighborhoods More Likely to Get Low Appraisals?". The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics. 16 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1023/a:1007727716513. ISSN 0895-5638. S2CID 152452718.

- Kamin, Debra (2020-08-25). "Black Homeowners Face Discrimination in Appraisals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- Pearman, Francis A.; Swain, Walker A. (2017-05-24). "School Choice, Gentrification, and the Variable Significance of Racial Stratification in Urban Neighborhoods". Sociology of Education. 90 (3): 213–235. doi:10.1177/0038040717710494. ISSN 0038-0407. S2CID 149108889.

- Edward., Goetz. Gentrification in black and white : the racial impact of public housing demolition in American cities. OCLC 902700292.

- Henig, Jeffrey R. (c. 1980). Gentrification and displacement in urban neighborhoods : a comparative analysis. OCLC 7898330.

- Goetz, Edward (2010-11-12). "Gentrification in Black and White". Urban Studies. 48 (8): 1581–1604. doi:10.1177/0042098010375323. ISSN 0042-0980. PMID 21949948. S2CID 5901845.

- Martinez-Cosio, Maria. "Coloring housing changes: Reintroducing race into gentrification" Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, TBA, New York, New York City, Aug 11, 2007.

- Kye, Samuel H. (May 2018). "The persistence of white flight in middle-class suburbia". Social Science Research. 72: 38–52. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.02.005. ISSN 0049-089X. PMID 29609744.

- Farley, Reynolds; Fielding, Elaine L.; Krysan, Maria (1997). "The residential preferences of blacks and whites: A four‐metropolis analysis". Housing Policy Debate. 8 (4): 763–800. doi:10.1080/10511482.1997.9521278.

- Iceland, J; Scopilliti, M (February 2008). "Immigrant residential segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas, 1990-2000". Demography. 45 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1353/dem.2008.0009. PMC 2831378. PMID 18390292.

- "Immigration and Socio-Spatial Segregation - Opportunities and Risks of Ethnic Self-Organisation"

- Lewis and Burd-Sharps (2015). Zeroing In on Place and Race. Social Science Research Council.

- Acevedo-Garcia, D.; McArdle, N.; Hardy, E.F.; Crisan, U.I.; Romano, B.; Norris, D.; Baek, M.; Reece, J. (2014). "The Child Opportunity Index: Improving Collaboration between Community Development and Public Health". Health Affairs. 33 (11): 1948–1957. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0679. PMID 25367989.

- Richards, Meredith P. (December 2014). "The Gerrymandering of School Attendance Zones and the Segregation of Public Schools". American Educational Research Journal. 51 (6): 1119–1157. doi:10.3102/0002831214553652. ISSN 0002-8312. S2CID 54202587.

- "TCF Study Finds U.S. Schools Underfunded by Nearly $150 Billion Annually". The Century Foundation. 22 July 2020.

- Sosina, Victoria E.; Weathers, Ericka S. (July 2019). "Pathways to Inequality: Between-District Segregation and Racial Disparities in School District Expenditures". AERA Open. 5 (3): 233285841987244. doi:10.1177/2332858419872445. ISSN 2332-8584. S2CID 203052026.

- Gaskin, Darrell J.; Dinwiddie, Gniesha Y.; Chan, Kitty S.; McCleary, Rachael R. (2012-04-23). "Residential Segregation and the Availability of Primary Care Physicians". Health Services Research. 47 (6): 2353–2376. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x. ISSN 0017-9124. PMC 3416972. PMID 22524264.

- Walton, Emily (December 2009). "Residential Segregation and Birth Weight among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 50 (4): 427–442. doi:10.1177/002214650905000404. ISSN 0022-1465. PMID 20099449. S2CID 14079528.

- Morland, Kimberly; Filomena, Susan (December 2007). "Disparities in the availability of fruits and vegetables between racially segregated urban neighbourhoods". Public Health Nutrition. 10 (12): 1481–1489. doi:10.1017/s1368980007000079. ISSN 1368-9800. PMID 17582241. S2CID 25495695.

- Havewala, Ferzana (August 2021). "The dynamics between the food environment and residential segregation: An analysis of metropolitan areas". Food Policy. 103: 102015. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.102015. ISSN 0306-9192. S2CID 230560043.

- Jesdale, Bill M.; Morello-Frosch, Rachel; Cushing, Lara (July 2013). "The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk–Related Land Cover in Relation to Residential Segregation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (7): 811–817. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205919. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 3701995. PMID 23694846.

- Plumer, Brad; Popovich, Nadja; Palmer, Brian (2020-08-24). "How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- "CLIMATE CHANGE and EXTREME HEAT EVENTS" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- VonLockette, Niki Dickerson (September 2010). "The Impact of Metropolitan Residential Segregation on the Employment Chances of Blacks and Whites in the United States". City & Community. 9 (3): 256–273. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01332.x. ISSN 1535-6841. S2CID 145410593.

- Yinger, John. 2001 "Housing Discrimination and Residential Segregation as Causes of Poverty," in Sheldon H. Danzinger and Robert H. Haveman, eds. Understanding Poverty. New York: Russell Sage Foundation

- Goering, J. (2005). The MTO experiment. In The Geography of Opportunity, ed X. de Souza Briggs, 219-246. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution

- Osypuk, T. L.; Tchetgen, E.T.; Acevedo-Garcia, D.; Earls, R.J.; Lincoln, A.; Schmidt, N.M.; Glymour, A.M. (2012). "Differential mental health effects on neighborhood relocation among vulnerable families: Results from a randomized trial". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (12): 1284–1294. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.449. PMC 3629812. PMID 23045214.

- Dawkins, Casey J. (2004). "Measuring the Spatial Pattern of Residential Segregation". Urban Studies. 41 (4): 833–851. doi:10.1080/0042098042000194133. S2CID 154287942.

- Mae, Hayes, Melissa (2006). The Building Blocks of Atlanta: Racial Residential Segregation and Neighborhood Inequity (Thesis). Georgia State University.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Strait, John B. (2001). "The Impact of Compositional and Redistributive Forces on Poverty Concentration". Urban Affairs Review. 37 (1): 19–42. doi:10.1177/10780870122185172. S2CID 153847318.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: DeKalb County, Georgia". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Fulton County, Georgia; Fulton County, Arkansas; DeKalb County, Georgia". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- "As Atlanta's Economy Thrives, Many Residents of Color Are Left Behind - The Annie E. Casey Foundation". The Annie E. Casey Foundation. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Tackle Poverty's Effects to Improve School Performance". Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "City Observatory - America's least (and most) segregated cities". City Observatory. 2020-08-17. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- Darden, Joe; Rahbar, Mohammad; Jezierski, Louise; Li, Min; Velie, Ellen (January 2010). "The Measurement of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Characteristics and Black and White Residential Segregation in Metropolitan Detroit: Implications for the Study of Social Disparities in Health". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 100 (1): 137–158. doi:10.1080/00045600903379042. ISSN 0004-5608. S2CID 129692931.

- "QuickFacts: Detroit city, Michigan; Michigan". United States Census Bureau.

- "History of Housing Discrimination Against African Americans in Detroit" (PDF). NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

- Moody, Heather A.; Darden, Joe T.; Pigozzi, Bruce Wm. (2016-08-18). "The Relationship of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Differences and Racial Residential Segregation to Childhood Blood Lead Levels in Metropolitan Detroit". Journal of Urban Health. 93 (5): 820–839. doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0071-8. ISSN 1099-3460. PMC 5052146. PMID 27538746.

Further reading

- Grigoryeva, Angelina and Ruef, Martin, "The Historical Demography of Racial Segregation," American Sociological Review 80 (Aug. 2015), 814–42.

- Moore, Eli; Montojo, Nicole; Mauri, Nicole (October 2019). Roots, Race, & Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area (Report). Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society.