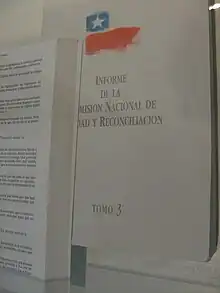

Rettig Report

The Rettig Report, officially The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report, is a 1991 report by a commission designated by Chilean President Patricio Aylwin (from the Concertación) detailing human rights abuses resulting in deaths or disappearances that occurred in Chile during the years of military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, which began on September 11, 1973 and ended on March 11, 1990. The report found that over 2,000 people had been killed for political reasons, and dozens of military personnel have been convicted of human rights abuses. In addition, many reforms have been made based on the recommendations of the report including an official reparations department.

.jpg.webp)

Background

The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, the eight-member committee that later wrote the Rettig Report, was set up shortly after Patricio Aylwin, Chile's first democratically elected president since Salvador Allende, took office following the 1989 election.[1] In addition to the eight members, the committee was chaired by Raúl Rettig, a former Chilean senator and ambassador to Brazil under Allende. In order to show impartiality, the commission contained four members each from camps of supporters of the Pinochet regime, and opponents of it.[1]

The eight-members of the commission were Jaime Castillo Velasco, José Luis Cea Egaña, Mónica Jiménez, Laura Novoa Vásquez, José Zalaquett Daher, Ricardo Martin Díaz, and Gonzalo Vial Correa (minister of Education 1978-79).

The commission was given large amounts of resources and access to official documents to ensure thoroughness, and the report was finalized in February 1991.[2] One criticism of the report is that it only focused on politically motivated murders and disappearances that occurred while Pinochet was dictator, and did not include other human rights violations. This issue was addressed in a second report commissioned in 2003 known as the Valech Report.[3]

Goals of the Report

On April 25, 1990, Aylwin issued Supreme Decree No. 355, officially creating the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation with the following goals:

- To create as complete a picture as possible of the most serious human rights violations

- To gather evidence to allow the creation of a list that identifies the victims' name, fate, and whereabouts

- To recommend reparations for the families of victims

- To recommend legal and administrative measures to prevent future violations[4]

Findings

The report determined that there were 2,115 victims of human rights violations and 164 victims of political violence between September 11, 1973 and the end of the Pinochet regime on March 11, 1990. This breaks down further to 1,068 victims confirmed to have been killed, 957 people who disappeared after their arrest, and an additional 90 killed by politically motivated private citizens. The report also was unable to come to a decision for 614 cases, and there were an additional 508 cases in which the nature of the violation did not fit the commission's mandate.[3] The commission found that the majority of the human rights violations were conducted in a sophisticated and systematic fashion in the years directly after Pinochet took power. The majority of the violations were perpetrated by the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), Chile's secret police force from 1973 to 1977.[3]

Legal Ramifications

As of May 2012, 76 agents had been condemned for violations of human rights and 67 were convicted: 36 in the Army, 27 in the Carabineros, 2 in the Air Force, one of the Navy and one in the Police. Three condemned agents died and six agents got conditional sentences. 350 cases, pertaining to disappeared persons, illegal detainees and torture, remain open. There are 700 military and civilian persons involved in these cases.[5] While some perpetrators have been convicted, prosecution has been difficult due to an amnesty law passed by the military regime in 1978 giving full legal protection to any individual implicated in human rights violations between 1973 and 1978.[3]

Recommendations

The report included the following recommendations to prevent future human rights violations in Chile:

- Ratification of international human rights treaties

- Modifying the national laws to match international standards of human rights law

- Assuring the independence of the judiciary

- Creating a society in which the armed forces, the police, and the security forces respect human rights

- Creating a permanent office to work to protect citizens from future human rights violations[6]

Over time, many of these recommendations were put into place in Chile, although progress was slow due to a lack of a legislative majority from Aylwin's party, and the continued influence of the military in politics.[3] One area where Aylwin was unable to make change was a failure to repeal the 1978 amnesty law.[2]

Aftermath

In a speech announcing the report's findings, President Aylwin apologized on behalf of the Chilean government for the murders and disappearances detailed in the report, and asked the military to do the same. The Chilean military, still headed at the time by Pinochet, refused to apologize and much of the armed forces community openly questioned the validity of the report.[1]

The Rettig Report's listing of a disappeared person as deceased and the victim of a human rights violation created a legal determination of the victim's situation. That would give the surviving family members certain benefits such as making it possible for them to resolve property and inheritance claims, apply for social security and any reparation benefits, as well as impacting the marital status of spouses.[4] This was made possible through the establishment of the "National Corporation for Reparation and Reconciliation".[3]

Other actions based on recommendations from the report that were eventually taken by later Chilean governments are:[7]

- The elimination in 1998 of the national holiday celebrating the 1973 coup.

- The Chilean military was stripped of its political power with the elimination of the military dominated National Security Council in 2005.

- The National Institute for Human Rights, a government agency that reports on human rights issues within Chile, was created in November 2009.[3]

Pinochet was also stripped of his parliamentary immunity in 2000, and was indicted by the Chilean Supreme Court along with other officers for killings which occurred after the original coup in 1973. He was put under house arrest with new charges in 2004, and died under house arrest in December 2006.[3]

The human rights violations in Chile were also looked at again in the Valech Report which was conducted between 2004 and 2005.[3]

See also

- Chilean Coup of 1973

- List of truth and reconciliation commissions

- Víctor Jara Stadium was a sports arena used as a detention and torture center listed on the report.

- Carlos Lorca

- Patio 29

- Villa Grimaldi Infamous torture center in Santiago.

- Colonia Dignidad is another detention and torture center listed.

- Valech Report is the report from the second truth commission in Chile, considered to have continued Rettig's work.

References

- Vasallo, Mark (2002). "Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: General Considerations and a Critical Comparison of the Commissions of Chile and El Salvador". The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. 33 (1): 153–182. ISSN 0884-1756. JSTOR 40176564.

- human-rights-and-the-politics-of-agreements-chile-during-president-aylwins-first-year-july-1991-109-pp, doi:10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-1309-0234

- "Truth Commission: Chile 90". United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Ensalaco, Mark (1994). "Truth Commissions for Chile and El Salvador: A Report and Assessment". Human Rights Quarterly. 16 (4): 656–675. doi:10.2307/762563. JSTOR 762563.

- Agence France Presse (6 July 2012). "Estudio revela que 76 son los agentes de la dictadura condenados por violaciones a DDHH". Chiliean Newspaper la Tercera. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Weissbrodt, David; Fraser, Paul (1992). "Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation". Human Rights Quarterly. 14 (4): 601–622. doi:10.2307/762329. JSTOR 762329.

- Chavez-Segura, Alejandro. "Can Truth Reconcile a Nation? Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in Argentina and Chile: Lessons for Mexico." Latin American Policy, vol. 6, no. 2, 2015, pp. 226-239. OhioLINK Electronic Journal Center, doi:10.1111/LAMP.12076.

External links

- Memoriaviva (Complete list of Victims, Torture Centres and Criminals - in Spanish)

- Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation (English translation of the Rettig report, PDF file)

- Truth Commission: Chile 90, Website with English translation of the report

- Human Rights Watch Report

- Compilation of Different Truth Commissions

- Protests in Chile regarding lasting impacts of Pinochet

- Víctor Jara, a famous victim of the Pinochet Regime