Atychodracon

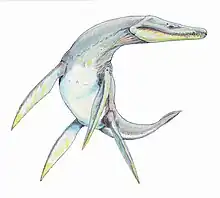

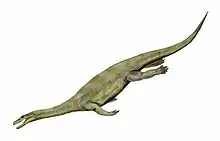

Atychodracon is an extinct genus of rhomaleosaurid plesiosaurian known from the Late Triassic - Early Jurassic boundary (probably early Hettangian stage) of England. It contains a single species, Atychodracon megacephalus, named in 1846 originally as a species of Plesiosaurus. The holotype of "P." megacephalus was destroyed during a World War II air raid in 1940 and was later replaced with a neotype. The species had a very unstable taxonomic history, being referred to four different genera by various authors until a new genus name was created for it in 2015. Apart from the destroyed holotype and its three partial casts (that survived), a neotype and two additional individuals are currently referred to Atychodracon megacephalus, making it a relatively well represented rhomaleosaurid.[1]

| Atychodracon Temporal range: Late Triassic-Early Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Referred specimen LEICS G221.1851, New Walk Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Rhomaleosauridae |

| Genus: | †Atychodracon Smith, 2015 |

| Type species | |

| †Atychodracon megacephalus (Stutchbury, 1846) | |

History of discovery

The type species of Atychodracon was first described and named by Samuel Stutchbury in January 1846, as a species of the wastebasket taxon Plesiosaurus. The specific name means "large-headed" in Greek in reference to the very large skull compared to the rest of the skeletal elements "Plesiosaurus" megacephalus had, relatively to other / actual species of Plesiosaurus.[2] The pliosauroid nature of "Plesiosaurus" megacephalus remained unnoted until a revision by Richard Lydekker in 1889. Lydekker recognized the rhomaleosaurid affinities of "P." megacephalus, but because he and Harry G. Seeley "refused steadfastly to recognize the generic and specific names proposed by one another", he moved "P." megacephalus to the genus Thaumatosaurus which was regarded by him as a replacement to Seeley's Rhomaleosaurus - creating the new combination T. megacephalus.[1][3]

The holotype of Atychodracon is BRSMG Cb 2335 and its casts and digital reproductions. BRSMG Cb 2335 represented a complete and articulated skeleton including the skull and lower jaw measuring 4.960 meters in total body length, and was one of several plesiosaurian specimens displayed in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery during the first half of the twentieth century. BRSMG Cb 2335, was collected from the Blue Lias Formation at the Street-on-the-Fosse village, located about 14 km northeast of Street, Somerset, England. The Blue Lias, also referred to as the Lower Lias, dates back to the Late Triassic - Early Jurassic boundary, thus includes the Rhaetian, Hettangian, and lower Sinemurian stages. BRSMG Cb 2335 came from the lowermost beds of the formation, and the area around Street probably originates below the first occurrence of Psiloceras planorbis ammonoid zone (pre-Planorbis beds), in the Psiloceras tilmanni Zone that immediately follows the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, meaning that an earliest Hettangian age is most likely for the specimen, about 201 million years ago. However, it is possible that some of the specimens from the area are from slightly younger deposits.[1]

BRSMG Cb 2335 was destroyed during a World War II air raid on 24 November 1940, however detailed descriptions and illustrations of the specimen as well as high quality historical photographs still exist to this day. Additionally, at least three casts are known, including: NHMUK R1309/1310 housed at the Natural History Museum, London, TCD.47762a+b at the Geology Museum, Trinity College Dublin, and BGS GSM 118410 at British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham. Each of the casts is a replica of parts of the original specimen, and comprises a representation of the skull, nine front neck vertebrae including the atlas-axis, and the right forelimb. In June 2014, three-dimensional digital models of BGS GSM 118410 were produced.[1]

Cruickshank (1994a) described LEICS G221.1851 as a neotype specimen for "P." megacephalus due to the destruction of BRSMG Cb 2335. LEICS G221.1851, nicknamed "The Barrow Kipper", represents a complete and well preserved skeleton housed at the New Walk Museum in Leicester, and was discovered at Barrow-upon-Soar, of Leicestershire, England. It was collected by William Lee during the early 1850s, from the Psiloceras planorbis Zone of Bottom Floor Limestone Member of Blue Lias, 2 meters above the local Rhaetian, thus dating to the early Hettangian. However, a 2015 revision of "P." megacephalus pointed out that according to International Code of Zoological Nomenclature article 51.1, designating a neotype in this case is not required since representations of the holotype exist, and are enough to define the species objectively. Thus, currently LEICS G221.1851 is treated as a specimen referred to Atychodracon megacephalus and not its type material.[1]

Two additional specimens, both housed at the National Museum of Ireland, are currently referable to A. megacephalus - NMING F10194, a partial skeleton that includes the skull but not the lower jaw from Street, and NMING F8749, a partial skeleton that includes a damaged skull and suffers from pyrite decay, from Barrow-upon-Soar. Both specimens also came from the lower Blue Lias, and likely date to the early Hettangian too. WARMS 10875, a complete skeleton from Wilmcote, Warwickshire was referred to "P." megacephalus in older publications, e.g. Cruickshank (1994a). However, based on its distinctive morphology and the results of a preliminary phylogenetic analysis, WARMS 10875 seems to represent a new unnamed rhomaleosaurid species potentially related to Atychodracon and Eurycleidus.[1][4]

Description

Atychodracon is a medium size carnivorous plesiosaurian, known from several individuals of about 4.9–5.8 m (16–19 ft) in total body length and 650 kg (1,430 lb) in body mass, with skulls measuring at about 80 cm.[1][5][6] Among such early plesiosaurs, Atychodracon had a relatively large skull with the skull being 16% of its total length. The premaxillary part of its snout is about equal in width and length with five premaxillary teeth. Other characteristics seen on the holotype skull include a palatine bone that contacts the internal naris, and a front to back oriented channel in front of the external naris. The front of interpterygoid spacing is elongated front to back and narrow from the mid to the sides. Its parabasisphenoid was gently keeled, and the sides of the lower jaw are bowed from the mid to the sides. The mandibular symphysial region is expanded to the sides, nearly equal in width and length. The bottom surface of the dentary close to the mandibular symphysis, to which the splenials contribute on the mid bottom side, shows diverging bars and a midline longitudinal crest. An arrow cleft is present on midline between the dentaries and a large lingual foramen is present on the lower jaw. A medial boss is present on the retroarticular projection.[1]

Atychodracon, based solely on the holotype, has 29-30 neck vertebrae including the atlas bone and axis, about 32 tail vertebrae, a projection on the front surface of the cervical ribs, a straight preaxial humerus margin, poorly defined radius and ulna facets on the humerus, a slightly shorter humerus than femur, a shorter ulna than radius, and a tibia and fibula equal length.[1]

Among other rhomaleosaurids, the material of Atychodracon has been mainly referred to two genera prior to its separation, namely Rhomaleosaurus and Eurycleidus. Recent studies find little kinship between Atychodracon and true Rhomaleosaurus spp., aside from traits that are shared between most rhomaleosaurids. In fact, all phylogenetic analyses that included representatives of Rhomaleosaurus and specimens now referable to Atychodracon, didn't find any close affinity. On the other hand, several phylogenetic analyses recovered Eurycleidus as the sister taxon of Atychodracon when both are included, which seems to imply a close kinship between the taxa, as originally suggested by Andrews (1922). Yet, this is not supported by all analyses, and despite the difficulty in directly comparing the two, several differences exist. The holotype of Eurycleidus lacks a skull, and the previously referable OUM J.28585 probably represents a new taxon, so little overlapping material exists between the holotypes of Atychodracon and Eurycleidus. However the following differences are notable: in Eurycleidus the midline cleft on the bottom surface of the mandibular symphysis is not bordered by the splenials from the back, like in Atychodracon. In Eurycleidus, an additional large asymmetrical cleft separates the splenials on the midline. Unlike the straight preaxial margin of the humerus of Atychodracon, it is concave in Eurycleidus. Additionally, Atychodracon shows a more stout and robust humerus, and a reverse relation in the radius to ulna lengths (the former being shorter than the letter in Eurycleidus). These distinctions suggest that while Atychodracon is fairly closely related to Eurycleidus, it represents a separate genus.[1]

Classification

In a revision of many pliosauroid taxa, Andrews (1922) was the first to recognize that "P." megacephalus is morphologically more closely related to "Plesiosaurus" arcuatus than to species of the Rhomaleosaurus/Thaumatosaurus complex. He concluded that the two species belong to the same genus, which he erected as Eurycleidus, with the type species being Eurycleidus arcuatus, and E. megacephalus as a referred species. Nevertheless, this was not followed by all authors, such Swinton (1930) who used T. megacephalus and later in 1948 P. megacephalus, to avoid confusion soon after the holotype was destroyed. This conservative name, "P." megacephalus, was followed by Taylor and Cruickshank (1989) and Taylor (1994). However, in 1994 Cruickshank designated a neotype for the species, and due to the Rhomaleosaurus/Thaumatosaurus issue being resolved in favor of the former (while Thaumatosaurus is a nomen dubium) he referred to it by the new combination, Rhomaleosaurus megacephalus.[1][3]

Adam S. Smith in his 2007 thesis on the anatomy and classification of the family Rhomaleosauridae, found the genus Rhomaleosaurus that became a wastebasket taxon itself to have only three valid species, and considered "P." megacephalus to be rather a second species of Eurycleidus as suggested by Andrews (1922).[7] Smith and Dyke (2008) recognized a fourth valid species in Rhomaleosaurus, and tentatively referred to "P." megacephalus as "Rhomaleosaurus" megacephalus. However, they recognized the need for a new genus name for "P." megacephalus, as was supported by their phylogenetic analysis of all valid Rhomaleosaurus species, and most valid rhomaleosaurids. The cladogram below follows the preliminary phylogenetic analysis of Smith & Dyke (2008), with the asterisk noting species recently removed from Rhomaleosaurus to their own genera.[4]

| Rhomaleosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladistic analyses by Ketchum & Benson, 2010, Benson et al., 2011, Ketchum & Benson, 2011, and various later studies found "R." megacephalus to be basal to the clade containing Rhomaleosaurus and Eurycleidus,[8][9] thus it should be in its own genus as suggested by Smith and Dyke (2008). Following this, the new genus name Atychodracon was erected by Smith in 2015 for "R." megacephalus, with the type species being Atychodracon megacephalus. The generic name is derived from Greek ατυχής, atychis, meaning "unfortunate" in reference to the unfortunate destruction of the holotype during a World War II air bombing in 1940, plus δράκωνe, drakon, meaning "dragon" - a common suffix in genus names of various mesozoic reptile groups.[1]

Atychodracon has been included on many occasions in various phylogenetic analyses, usually as "Rhomaleosaurus" megacephalus. In these analyses, the referred LEICS G221.1851 was used to represent the species due to its higher completeness and being the proposed neotype. The referral of this LEICS G221.1851 to Atychodracon is relatively strong, meaning that this should not affect Atychodracon position in the topology.[1] The following two cladograms are simplified after two recent analyses, showing only the relationships within Rhomaleosauridae, and a few basal taxa whose position within the family is highly uncertain.

Following Benson et al. (2012):[10]

| Plesiosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following Benson & Druckenmiller (2014), with Macroplata and Eurycleidus excluded, and Borealonectes added:[11]

| Plesiosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Smith, Adam S. (22 April 2015). "Reassessment of 'Plesiosaurus' megacephalus (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, UK". Palaeontologia Electronica. 18 (1): 1–20.

- Stutchbury, Samuel (January 1846). "Description of a new species of Plesiosaurus, in the Museum of the Bristol Institution". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 2 (1–2): 411–417. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1846.002.01-02.58. S2CID 131463215.

- Adam S. Smith; Peggy Vincent (2010). "A new genus of pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Jurassic of Holzmaden, Germany" (PDF). Palaeontology. 53 (5): 1049–1063. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00975.x.

- Adam S. Smith & Gareth J. Dyke (2008). "The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 95 (10): 975–980. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..975S. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. PMID 18523747. S2CID 12528732.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2022). The Princeton Field Guide to Mesozoic Sea Reptiles. Princeton University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780691193809.

- Smith, A.S. (2007). "Chapter 3 – Material and palaeontological approaches" (PDF). Anatomy and Systematics of the Rhomaleosauridae (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) (PDF). pp. 27–58.

- Adam S. Smith (2007). "Anatomy and systematics of the Rhomaleosauridae (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria)" (PDF). Ph.D. Thesis, University CollegeDublin.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Hilary F. Ketchum; Leslie F. Noè; Marcela Gómez-Pérez (2011). "New information on Hauffiosaurus (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) based on a new species from the Alum Shale Member (Lower Toarcian: Lower Jurassic) of Yorkshire, UK". Palaeontology. 54 (3): 547–571. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01044.x. S2CID 55436528.

- Ketchum, Hilary F.; Benson, Roger B. J. (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129.

- Roger B. J. Benson; Mark Evans; Patrick S. Druckenmiller (2012). "High Diversity, Low Disparity and Small Body Size in Plesiosaurs (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31838. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731838B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031838. PMC 3306369. PMID 22438869.

- Benson, R. B. J.; Druckenmiller, P. S. (2013). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455. S2CID 19710180.

.png.webp)