Richard A. Ballinger

Richard Achilles Ballinger (July 9, 1858 – June 6, 1922) was mayor of Seattle, Washington, from 1904–1906, Commissioner of the General Land Office from 1907–1908 and U.S. Secretary of the Interior from 1909–1911.

Richard A. Ballinger | |

|---|---|

| |

| 24th United States Secretary of the Interior | |

| In office March 6, 1909 – March 12, 1911 | |

| President | William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | James R. Garfield |

| Succeeded by | Walter L. Fisher |

| 31st Commissioner of the General Land Office | |

| In office January 28, 1907 – January 14, 1908 | |

| President | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | William A. Richards |

| Succeeded by | Fred Dennett |

| 24th Mayor of Seattle | |

| In office March 21, 1904 – March 19, 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas J. Humes |

| Succeeded by | William Hickman Moore |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard Achilles Ballinger July 9, 1858 Boonesboro, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | June 6, 1922 (aged 63) Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lake View Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Julia Bradley |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Williams College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Early life and Seattle career

Ballinger was born in Boonesboro, Iowa, the son of Richard Henry Ballinger and Mary Elizabeth Norton. In 1884, he graduated from Williams College, where he was a member of the Zeta Psi fraternity.[1]

Ballinger passed the bar exam in 1886 and began practicing law in Seattle. He married Julia Albertson Bradley later that year, on October 26. The couple ultimately had two sons, (Edward Bradley Ballinger and Richard Talcott Ballinger).

Following the scandal-prone Yukon Gold Rush era administration of Thomas J. Humes, Ballinger was elected Seattle's mayor in 1904. With the support of the downtown business elite, he cracked down somewhat (but not heavily) on vice, and opposed labor unions. Ballinger later proved a roadblock to the city's strong municipal ownership movement.[2] He also named Lake Ballinger in Snohomish County north of the city for his father, Col. Richard Ballinger.

Federal career and scandal

After serving as the mayor of Seattle, Ballinger joined the administration of President Theodore Roosevelt and served as commissioner of the General Land Office from 1907 until 1908. In 1909, Ballinger helped organize the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition, a World's Fair to highlight development in the Northwest.

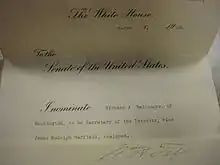

In 1909 despite previous promises to retain ex-President Roosevelt's cabinet officers, newly elected President William Howard Taft appointed Ballinger to replace conservationist (and fellow Ohioan) James R. Garfield as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.[3] One of his first acts was to revoke executive protection of lands potentially subject to development of hydroelectric energy pending surveys, restoring them to the public domain for leasing. Progressives feared that hydroelectric monopolies would grab such sites either to control or preclude development and would then dictate energy prices, since 13 companies (including General Electric and Westinghouse) already controlled more than a third of waterpower resources as Roosevelt left office. However, that restoration soon provoked a scandal. In August, in conjunction with the National Irrigation Conference in Spokane, Washington, a United Press reporter published a story about 15,868 acres of land in Montana being sold to large corporations (General Electric, Guggenheim and Amalgamated Copper). Ballinger at first ignored the story, then accused reporters of opposing development in the West.[4] Although that Montana waterpower story proved to be overblown, accusations of favoritism continued to dog Ballinger as Secretary of the Interior.

The most serious charges involved coal development in the Chugach National Forest by a Seattle developer and Ballinger crony, Clarence Cunningham, and financed by a corporation associated with J. P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family of New York City. The group had staked 33 claims, although Alaska land laws were designed to foster small farmers and prevent monopoly and thus required each claimant to prove that he or she was acting on his or her own behalf, as well as limited each claimant to 160 acres. While land commissioner, Ballinger granted the developer special access to government files. During the several month gap in 1908 between his employment as land commissioner and interior secretary, Ballinger acted as an agent for the Cunningham/Morgan/Guggenheim development group with the federal government, lobbying then Interior Secretary Jim Garfield. Upon becoming Interior Secretary, Ballinger reassigned General Land Office investigator Louis R. Glavis, and ultimately fired him after he complained to Gifford Pinchot (head of the Forestry Bureau and thus responsible for the Chugach, although also subordinate to the Interior Secretary), President Taft and cooperated with the press.[5]

A series of muckraking articles, including Glavis's in the November issue of Collier's Weekly roused the conservationists. An article in Hampton's even accused President Taft of being part of a conspiracy hatched at the 1908 Republican Convention. Ballinger again dismissed the controversy and President Taft appeared to want the ordeal to end, maintaining that both Ballinger and Pinchot remained committed to Roosevelt's conservation policies. Ballinger, however, threatened to resign unless Taft consented to a congressional investigation to exonerate him, and in December sent a letter to Washington state's Republican senator Wesley Jones demanding a complete investigation.[6]

Although even Charles Taft advised the President to ask for Ballinger's resignation, Taft stood by his appointee, and attorney general George Wickersham even backdated to September 11, 1909 a report concerning Glavis' firing. After a Washington insider warned Collier that Ballinger planned to sue his magazine after the planned "whitewash", it hired Louis D. Brandeis as its counsel. Pinchot went public with his differences with Ballinger's approach and his office delivered another report to the Senator Dolliver, Republican chair of the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry. This prompted Taft to fire Pinchot as well, while Roosevelt was in Africa.[7] During the special committee's hearings, both Glavis and Pinchot testified, and testimony about the backdating by a stenographer prompted Taft to take responsibility for ordering it, though that stenographer and other employees were also fired. Brandeis's questioning made Ballinger's anti-conservationism clear, but did not unearth anything so serious as to warrant criminal charges.[8] Nonetheless, public confidence in Ballinger's leadership of the Interior Department had waned.

After the Republican party lost heavily in the midterm elections that November, Ballinger finally resigned on March 12, 1911. Taft had replaced Pinchot with Henry Graves, who was committed to protecting American forests, and Ballinger helped Taft to secure a new law which allowed Taft to withdraw public lands from private development, thus allowing them to protect as many acres in one term as Roosevelt had in nearly two terms.[9] However, the series of Ballinger-related scandals, Taft's loyalty to his embattled appointee, and Ballinger's refusal to resign for more than nine additional months—combined with controversy over the Payne–Aldrich tariff—split the Republican Party and helped to turn the tide of the 1912 election against Taft.

Death

Ballinger returned to the private practice of law in Seattle, Washington, where he died on June 6, 1922, and was buried at the Lake View Cemetery.[10]

His wife Julia Albertson Ballinger (1864-1961) bore their sons Edwin B. Ballinger (1899-) and Richard Talcott Ballinger (1898-1971).

See also

Notes

- Baird, William Raymond (1915). Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities, pp. 349–355.

- Berner, Richard C. (1991), Seattle 1900–1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration, Seattle: Charles Press, ISBN 0-9629889-0-1. p. 111.

- Goodwin, p. 561-562.

- Goodwin, p. 606-610.

- Goodwin, p. 610-614.

- Goodwin, p. 616-618.

- Goodwin, p. 619-621.

- Goodwin, p. 622-626.

- Goodwin, p. 627.

- My Edmonds News