Shipyard Railway

The Shipyard Railway was an electric commuter rail/interurban line that served workers at the Richmond Shipyards in Richmond, California, United States, during World War II. It was funded by the United States Maritime Commission and was built and operated by the Key System, which already operated similar lines in the East Bay. The line ran from a pair of stations on the Emeryville/Oakland border – where transfer could be made to other Key System lines – northwest through Emeryville, Berkeley, Albany, and Richmond to the shipyards. It operated partially on city streets and partially on a dedicated right-of-way paralleling the Southern Pacific Railroad mainline.

| Shipyard Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Car #509 in Richmond | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | United States Maritime Commission | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | East Bay, California, US | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Key System | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | January 18, 1943 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | September 30, 1945 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 11.5 miles (18.5 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Overhead line, 600 V DC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Maritime Commission authorized the line in June 1942 over two competing proposals and construction began that August. It was built quickly with available materials, including rails reused from other lines and a bridge constructed from old turntables. The line operated with former elevated railway cars from New York City, which were rebuilt for use on the Shipyard Railway. Service began to Shipyard #2 on January 18, 1943, with two extensions to the other shipyards over the following month. It closed on September 30, 1945, after the conclusion of the war. Most of the 90 cars were later scrapped, but two are preserved at the Western Railway Museum.

Route

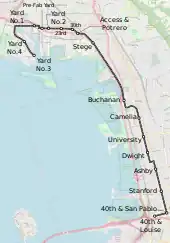

The southern terminus of the line was at Yerba Buena Avenue (40th Street)[lower-alpha 1] and Louise Street on the Emeryville/Oakland border. A fare controlled platform was built for the Shipyard trains. Connections could be made there with Key System routes A and B, which turned south on Louise Street, outside of fare control. The line ran east on 40th Street (on the south side of the Key System mainline) to San Pablo Avenue, where a pair of fare controlled platforms were located; connections could be made there with other Key System routes outside of fare control.[1][lower-alpha 2]

The line ran north on San Pablo Avenue, turned west for two blocks on Grayson Street[lower-alpha 3], then continued north on Ninth Street.[1][2] Splitting from Ninth Street, it crossed Codornices Creek and ran diagonally northwest on a private right-of-way across Albany Village, a federal housing project for war workers. A curved trestle bridge brought the line over the main line of the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP). It ran north on dedicated tracks between the Eastshore Highway and the Southern Pacific tracks.[1] Wigwags were used at grade crossings on this segment.[4]: 100

The line turned west along Potrero Avenue in Richmond, reaching Shipyard #2 at 14th Street.[1] After the stop at the Pre-fab Yard (10th Street), it turned north on 8th Street to Cutting Boulevard. It ran west on Cutting Boulevard with a stop at Shipyard #1 at 5th Street.[5] Near Canal Boulevard, the line turned south onto private right-of-way, with stops at Shipyard #4 and Shipyard #3.[6]

The line was fully double track except for Grayson Street and two short sections in Richmond.[7] Express trains at shift changes served only the shipyard stops and the Key System transfer points at 40th Avenue. Local trains ran every 35–40 minutes and served additional local stops in Emeryville, Berkeley, Albany, and Richmond.[8][1] Running time was about 45 minutes for local trains and several minutes faster for express trains.[8]

History

As the Richmond Shipyards were expanded at the beginning of World War II, mass transit was needed to bring East Bay workers to the shipyards.[4]: 85 Two "belt line" proposals were advanced in early 1942. "Plan 1", created by an Oakland mayoral commission, would have run from San Leandro to the shipyards.[9] It would have reused several abandoned Interurban Electric Railway (IER) lines: the Dutton Avenue line (some of which had been taken over by the Key System), tracks along the SP mainline, the 7th Street Line, and the 9th Street Line. New trackage would have been built from Solano Avenue along Panhandle Boulevard (now Carlson Boulevard) and Cutting Boulevard.[10] An alternate proposal by a business association would have used existing Western Pacific Railroad, SP, and Santa Fe Railway tracks.[9] On June 6, 1942, the United States Maritime Commission authorized the Key System to construct and operate a line connecting the Richmond Shipyards to existing mass transit lines in Oakland. The "belt line" proposals were rejected at that time.[3]

The line was built from scrap and available materials, as the war made regular construction materials unavailable. The portion on San Pablo Avenue shared the tracks of the #2 streetcar line of Key System subsidiary Oakland Traction Company, while the Ninth Avenue portion reused part of a 1941-abandoned IER line.[2] Rails were salvaged from other defunct lines, including portions of the IER, abandoned Key System streetcar lines, and even the Pacific Electric Railway in Los Angeles.[11] A new quarry was opened in Albany to provide track ballast, as existing quarries were at capacity.[11]

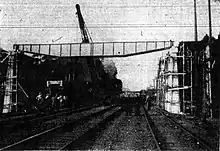

Overhead lines were reused from Key System streetcar lines and from the Bay Bridge. (Key System cars used third rail on the bridge, and the Sacramento Northern Railway and IER had discontinued service using the bridge in 1941).[11][2] Two defunct IER substations were relocated to provide power.[2] For the trestle over the SP mainline, bridge beams were fashioned out of used SP turntables from Bayshore and Tracy.[11] Timbers were reused from the Key System mole (pier), which had been abandoned after the completion of the Bay Bridge.[7]

The line was constructed by the Key System under a $1.65 million contract (equivalent to $22 million in 2021) from the Marine Commission.[13] Around-the-clock construction began on August 3, 1942.[14] Testing of trains on Ninth Avenue began on December 1, 1942.[15] The line opened as far as Shipyard #2 on January 18, 1943.[1][16] It was extended to Shipyard #1 on February 1, and to Shipyard #3 on February 22.[5][6][17] This completion allowed most bus service to the shipyards – which used scarce gasoline and tire rubber – to be discontinued.[6]

Built for 50,000 passengers a day, the Shipyard Railway only operated at 20% capacity; it was heavily used at shift changes but poorly used at other times.[15][18][12] Although it was planned to primarily serve riders from Oakland and San Francisco, the fare structure discouraged ridership from those points[lower-alpha 4], and the highest ridership was within Richmond.[18] A 1945 government report noted that "The shipyard management actually went out of its way to propagandize against the railway almost as soon as it started service and criticized Key for schedules which were specified by the shipyard's own staff."[18]

The line was "half a century out of date the day it opened"; the old wooden cars rode roughly and had uncomfortable seating.[12] Because construction was done cheaply with available materials, the track quality deteriorated quickly. By early 1945, most curves were no longer smooth, and two had significant kinks.[18] Shipbuilding continued even after the war ended in August 1945, but many workers switched to private automobiles as gasoline rationing ended. The Shipyard Railway was offered to the Key System, but the Key declined, viewing the line as unprofitable. It would have required substantial reconstruction for continued service, as well as new trackage to serve downtown Richmond.[12] Service ended on September 30, 1945, and the line was quickly dismantled.[12][4]: 85

Rolling stock

For unknown reasons, the Maritime Commission did not acquire rolling stock from the IER or the Northwestern Pacific Railroad interurban lines, which had also been abandoned in 1941.[12] Instead, the commission purchased 90 obsolete New York City elevated ("El") cars awaiting scrap. These wood-bodied cars had been built in 1887 for the IRT Second Avenue Line as coaches pulled by steam locomotives. They were converted for electric multiple unit operation in 1900, and retired when the elevated line closed in 1942.[20][21] The elevated cars were purchased by the Maritime Commission in June 1942 and overhauled in the Key System's Emeryville shops that August.[12] The commission supplied maritime gray paint for the cars.[21]

The elevated cars had been built for high-level platforms in New York. Wooden platforms were installed at the express stops.[19][22] Local trains were operated with Key System "bridge units" until a small number of the elevated cars were refitted with folding steps to allow them to serve street-level stops.[4]: 101 The cars were operated as married pairs. One car in each pair had an ex-IER pantograph, which replaced the third rail equipment used in New York.[21][2] Typical train lengths were four to six cars.[21][12]

After the line's closure, most of the cars were scrapped or sold off for use as sheds or bunkhouses.[21][4]: 101 Married pair #561 and #563 were purchased by the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway and Locomotive Historical Society. They remained at the Key System yard in Emeryville until 1960, when they were moved to the Western Railway Museum for preservation.[4]: 100 [20]

References

- "New Richmond Shipyard Railway Starts Operation Monday!". Oakland Tribune. January 17, 1943. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com. (Map detail)

- Ford, Robert S. (1977). Red Trains in the East Bay. Interurban Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0-916374-27-0.

- "Key Shipyard Rail Plan O.K.'d". Oakland Tribune. June 6, 1942. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rice, Walter; Echeverria, Emiliano (2007). The Key System: San Francisco and the Eastshore Empire. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738547220.

- "Shipyard Railway Extends Service". Oakland Tribune. January 30, 1943. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Shipyard Rail Runs Extended". Oakland Tribune. February 21, 1943. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Road Cost $1,600,000". Oakland Tribune. January 17, 1943. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- "[Untitled timetable]" (PDF). Key System. May 27, 1945.

- "Traffic Plan Muddle Put Before U.S." Oakland Tribune. May 16, 1942. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bay Belt Line To Richmond Under Study". Oakland Tribune. May 11, 1942. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Shipyard Railway Monument to Ingenuity of Key Engineers". Oakland Tribune. January 17, 1943. pp. 16, 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- Duke, Donald (2000). Electric Railways Around San Francisco Bay: Volume Two. Golden West Books. pp. 147–151. ISBN 0870951165.

- Fernhout, D.W. (January 17, 1943). "Rail Line to Open Jan. 18". Oakland Tribune. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Shipyard Trains To Run Dec. 1". Oakland Tribune. August 1, 1942. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Richmond Shipyard Railway Makes Test Run Of 'El' Cars". Oakland Tribune. December 2, 1942. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New Transportation Will Commence Operation Tomorrow". Oakland Tribune. January 17, 1943. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- "Shipyard Railway Now Complete". Oakland Tribune. February 20, 1943. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- Report on Key System, Oakland, California. United States Office of Defense Transportation. February 1945. p. 15 – via Google Books.

- "Shipyard Line Starts Monday". Oakland Tribune. January 17, 1943. pp. 15, 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Key System 561". Western Railway Museum. Bay Area Electric Railroad Association.

- Trimble, Paul C. (1977). Interurban Railways of the Bay Area. Valley Publishers. pp. 47, 48. ISBN 0913548472.

- "Shipyard Rails Rushed". Oakland Tribune. September 13, 1942. p. 37 – via Newspapers.com.

Notes

- Now part of Mandela Parkway. The modern 40th Street is on a different alignment to the north.

- Some sources incorrectly give 40th Street and San Pablo as the terminus.[2]

- Some secondary sources incorrectly place the jog on Heinz Street, one block to the south, which was the original planned route.[2][3]

- Fare was one token or ten cents within Richmond, versus two tokens or twenty cents from points further south. Tokens cost 50 cents for 7 at that time.[1][19]

Further reading

- Demoro, Harre (1985). The Key Route, Part 2: Transbay Commuting by Train and Ferry (Interurbans Special 97). Interurban Press. ISBN 978-0916374686.

- Lee, Warren; Lee, Catherine (2000). A selective history of the Codornices-University Village, the City of Albany & environs: With special attention given to the Richmond Shipyard Railway and the Albany Hill and shoreline. Albuquerque, N.M.: Belvidere Delaware Railroad Company Enterprises, Ltd. ISBN 978-0967564609.

- Sappers, Vernon J. (1948). From Shore to Shore: The Key Route. Peralta Associates.

External links

![]() Media related to Shipyard Railway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shipyard Railway at Wikimedia Commons

- Western Railway Museum: Key System 561 and Key System 563