Rijksmuseum

The Rijksmuseum (Dutch: [ˈrɛiksmyˌzeːjʏm] ⓘ) is the national museum of the Netherlands dedicated to Dutch arts and history and is located in Amsterdam.[10][11] The museum is located at the Museum Square in the borough of Amsterdam South, close to the Van Gogh Museum, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and the Concertgebouw.[12]

.jpg.webp) Rijksmuseum at the Museumplein in 2019 | |

| Established | 19 November 1798[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | Museumstraat 1[2] Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Type | |

| Collection size | 1 million objects[3] |

| Visitors |

|

| Director | Taco Dibbits [9] |

| President | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer[9] |

| Public transit access | Tram: 2 |

| Website | www |

The Rijksmuseum was founded in The Hague on 19 November 1798 and moved to Amsterdam in 1808, where it was first located in the Royal Palace and later in the Trippenhuis.[1] The current main building was designed by Pierre Cuypers and first opened in 1885.[3] On 13 April 2013, after a ten-year renovation which cost € 375 million, the main building was reopened by Queen Beatrix.[13][14][15] In 2013 and 2014, it was the most visited museum in the Netherlands with record numbers of 2.2 million and 2.47 million visitors.[6][16] It is also the largest art museum in the country.

The museum has on display 8,000 objects of art and history, from their total collection of 1 million objects from the years 1200–2000, among which are some masterpieces by Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Johannes Vermeer. The museum also has a small Asian collection, which is on display in the Asian pavilion.

History

The collection of the Rijksmuseum was built over a period of 200 years and did not originate from a royal collection incorporated into a national museum. Its origins were modest, with its collection fitting into five rooms at in Huis ten Bosch palace in The Hague. Although the seventeenth century was beginning to be recognized as the key period in Dutch art, the museum did not then hold paintings by Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Jan Steen, Johannes Vermeer, or Jacob van Ruisdael. The collection was built up by purchase and donation. Napoleon had carried off the stadholder's collection to Paris; the paintings were returned to The Netherlands in 1815 but housed in the Mauritshuis in The Hague rather than the Rijksmuseum. With the founding of the Rijksmuseum in 1885, holdings from other entities were brought together to establish the Rijksmuseum's major collections.[17]

18th century

In 1795, the Batavian Republic was proclaimed; its Minister of Finance Isaac Gogel argued that a national museum, following the French example of The Louvre, would serve the national interest. On 19 November 1798, the government decided to found the museum.[1][18]

19th century

On 31 May 1800, the National Art Gallery (Dutch: Nationale Kunst-Galerij), precursor of the Rijksmuseum, opened in Huis ten Bosch in The Hague. The museum exhibited around 200 paintings and historic objects from the collections of the Dutch stadtholders.[1][18] In 1805, the National Art Gallery moved within The Hague to the Prince William V Gallery, on the Buitenhof.[1] In 1806, the Kingdom of Holland was established by Napoleon Bonaparte. On the orders of king Louis Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon, the museum moved to Amsterdam in 1808. Paintings owned by that city, such as The Night Watch by Rembrandt, became part of the collection. In 1809, the museum opened in the Royal Palace in Amsterdam.[1]

In 1817, the museum moved to the Trippenhuis. The Trippenhuis turned out to be unsuitable as a museum. In 1820, the historical objects were moved to the Mauritshuis in The Hague and in 1838, the 19th-century paintings "of living masters" were moved to King Louis Bonaparte's former summer palace Paviljoen Welgelegen in Haarlem.[1]

"Did you know that a large, new building will take the place of the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam? That's fine with me; the Trippenhuis is too small, and many paintings hang in such a way that one can't see them properly."

– Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo in 1873.[19] Vincent himself would later become a painter and some of his works would be hanging in the museum.

In 1863, there was a design contest for a new building for the Rijksmuseum, but none of the submissions was considered to be of sufficient quality. Pierre Cuypers also participated in the contest and his submission reached the second place.[20]

In 1876, a new contest was held and this time Pierre Cuypers won. The design was a combination of gothic and renaissance elements. The construction began on 1 October 1876. On both the inside and the outside, the building was richly decorated with references to Dutch art history. Another contest was held for these decorations. The winners were B. van Hove and Frantz Vermeylen for the sculptures, Georg Sturm for the tile panels} and painting and W.F. Dixon for the stained glass. The museum was opened at its new location on 13 July 1885.[20]

In 1890, a new building was added a short distance to the south-west of the Rijksmuseum. As the building was made out of fragments of demolished buildings, the building offers an overview of the history of Dutch architecture and has come to be known informally as the 'fragment building'. It is also known as the 'south wing' and is currently (in 2013) branded the Philips Wing.

20th century

In 1906, the hall for The Night Watch was rebuilt.[20] In the interior more changes were made between the 1920s and 1950s – most multi-coloured wall decorations were painted over. In the 1960s exposition rooms and several floors were built into the two courtyards. The building had some minor renovations and restorations in 1984, 1995–1996 and 2000.[21]

A renovation of the south wing of the museum, also known as the 'fragment building' or 'Philips Wing', was completed in 1996, the same year that the museum held its first major photography exhibition featuring its extensive collection of 19th-century photos.[22]

21st century

In December 2003, the main building of the museum closed for a major renovation. During this renovation, about 400 objects from the collection were on display in the 'fragment building', including Rembrandt's The Night Watch and other 17th-century masterpieces.[23]

The restoration and renovation of the Rijksmuseum are based on a design by Spanish architects Antonio Cruz and Antonio Ortiz. Many of the old interior decorations were restored and the floors in the courtyards were removed. The renovation would have initially taken five years, but was delayed and eventually took almost ten years to complete. The renovation cost €375 million.[14]

The reconstruction of the building was completed on 16 July 2012. In March 2013, the museum's main pieces of art were moved back from the 'fragment building' (Philips Wing) to the main building. The Night Watch returned to the Night Watch Room, at the end of the Hall of Fame. On 13 April 2013, the main building was reopened by Queen Beatrix.[13] On 1 November 2014, the Philips Wing reopened with the exhibition Modern Times: Photography in the 20th Century.

List of directors

- Cornelis Sebille Roos[1]

- Cornelis Apostool (1808–1844)[1]

- Jan Willem Pieneman (1844–1847)[24]

- Johann Wilhelm Kaiser (1873–1883)

- Frederik Daniël Otto Obreen (1883–1896)[25]

- Barthold Willem Floris van Riemsdijk (1897–1921)[26]

- Frederik Schmidt-Degener (1921–1941)[27]

- David Röell (1945–1959)[28]

- Arthur F.E. van Schendel (1959–1975)[29]

- Simon Levie (1975–1989)[29]

- Henk van Os (1989–1996)[30]

- Ronald de Leeuw (1996–2008)[31]

- Wim Pijbes (2008–2016)[32]

- Taco Dibbits (2016–present)[33]

Building

The building of the Rijksmuseum was designed by Pierre Cuypers and opened in 1885. It consists of two squares with an atrium in each centre. In the central axis is a tunnel with the entrances at ground level and the Gallery of Honour at the first floor. The building also contains a library. The fragment building, branded Philips wing, contains building fragments that show the history of architecture in the Netherlands. The Rijksmuseum is a rijksmonument (national heritage site) since 1970[34] and was listed in the Top 100 Dutch heritage sites in 1990. The Asian pavilion was designed by Cruz y Ortiz and opened in 2013.

According to Muriel Huisman, Project Architect for the Rijksmuseum's renovation, "Cruz y Ortiz always like to look for synergy between old and new, and we try not to explain things with our architecture.” With the Rijks, “there’s no cut between old and new; we’ve tried to merge it. We did this by looking for materials that were true to the original building, resulting in a kind of silent architecture."[35]

The Rijksmuseum was located in the Trippenhuis between 1817 and 1885.

The Rijksmuseum was located in the Trippenhuis between 1817 and 1885. Drawing of the design by Pierre Cuypers in 1876.

Drawing of the design by Pierre Cuypers in 1876. Front of Cuypers' building, circa 1895.

Front of Cuypers' building, circa 1895. View of the facade by night.

View of the facade by night.- Video of the Rijksmuseum (2016).

Collection

The collection of the Rijksmuseum consists of 1 million objects and is dedicated to arts, crafts, and history from the years 1200 to 2000. Around 8,000 objects are currently on display in the museum.[3]

The collection contains more than 2,000 paintings from the Dutch Golden Age by notable painters such as Jacob van Ruisdael, Frans Hals, Johannes Vermeer, Jan Steen, Rembrandt, and Rembrandt's pupils.[3]

The museum also has a small Asian collection which is on display in the Asian pavilion.[3]

Some of the more unusual items in the collection include the royal crest from the stern of HMS Royal Charles which was captured in the Raid on the Medway, the Hartog plate and the FK35 Bantam biplane.

In 2012,[36] the museum made some 125,000 high-resolution images available for download via its Rijksstudio webplatform,[37] with plans to add another 40,000 images per year until the entire collection of one million works is available, according to Taco Dibbits, director of collections.[38][39] As of January 2021, the Rijksstudio hosts 700,000 works, available under a Creative Commons 1.0 Universal license, essentially copyright-free and royalty-free.

Gallery

Portrait of a Young Couple (1622) by Frans Hals

Portrait of a Young Couple (1622) by Frans Hals Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem (1630) by Rembrandt

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem (1630) by Rembrandt

The Night Watch (1642) by Rembrandt

The Night Watch (1642) by Rembrandt Banquet at the Crossbowmen’s Guild in Celebration of the Treaty of Münster (1648) by Bartholomeus van der Helst

Banquet at the Crossbowmen’s Guild in Celebration of the Treaty of Münster (1648) by Bartholomeus van der Helst The Threatened Swan (c. 1650) by Jan Asselijn

The Threatened Swan (c. 1650) by Jan Asselijn The Milkmaid (c. 1657–58) by Johannes Vermeer

The Milkmaid (c. 1657–58) by Johannes Vermeer The Jewish Bride (c. 1667) by Rembrandt

The Jewish Bride (c. 1667) by Rembrandt

Landscape with Waterfall (1660s) by Jacob van Ruisdael

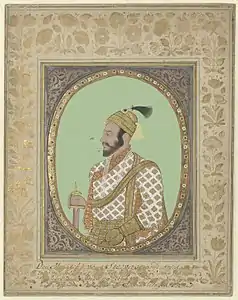

Landscape with Waterfall (1660s) by Jacob van Ruisdael Shivaji's portrait (1680s) in the Rijksmuseum (1630-80)

Shivaji's portrait (1680s) in the Rijksmuseum (1630-80)

Special exhibitions

Rembrandt

in 2019, to mark the 350th anniversary of the artist's death, the museum mounted an exhibition of all the works by Rembrandt in its collection. Consisting of 22 paintings, 60 drawings and over 300 prints, this was the first time they had all been exhibited together. Principal features were the marriage portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit along with the presentation of the Night Watch immediately before its planned restoration. The exhibition ran from February to June.[40]

Slavery in the Dutch Empire

After previous temporary exhibitions on art historical themes, the Rijksmuseum in 2021 presented an exhibition on the history of slavery in the Dutch colonial Empire, with more than a million people forced into slavery.[41] It covered trans-Atlantic slavery from the 17th to the 19th century in Suriname, Brazil and the Caribbean, as well as Dutch colonial slavery in South Africa and Asia, where the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) were engaged in slavery. Besides objects, such as a wooden block for locking slaves, paintings, archival documents, oral sources, poems and music, the exhibition also presented connections of the slavery system at home in the Netherlands.[42] In the permanent collection, labels were added to 77 paintings and objects that had been seen as symbols of the country's wealth and power to indicate previously hidden links to slavery.[43]

The exhibition was presented both physically in the museum from May to August 2021 and in an online version.[44] It was complemented by audio tours and videos relating personal and real-life stories[45] as well as an accompanying book titled Slavery.[46]

Vermeer

From 10 February until June 2023 the Rijksmuseum began to exhibit the biggest collection of Vermeers ever, with 28 of the known 37 works on display. Curator Pieter Roelofs called it a "once in a lifetime" event.[47][48] All time slot reservations were quickly sold out.[49]

Number of visitors

| year | visitors | year | visitors | year | visitors | year | visitors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 1,412,000[50] | 2000 | 1,146,438[51] | 2010 | 896,393[52] | 2020 | 675,325[53] | |||

| 2001 | 1,015,561[51] | 2011 | 1,010,402[52][lower-alpha 1] | 2021 | 623,923[53] | |||||

| 1992 | 1,216,103[54][lower-alpha 2] | 2002 | 1,100,488[55] | 2012 | 894,058[56] | |||||

| 1993 | 936,400[54] | 2003 | 833,450[55][lower-alpha 3] | 2013 | 2,246,122[16] | |||||

| 1994 | 1,002,000[57][58][lower-alpha 4] | 2004 | 812,102[59] | 2014 | 2,474,352[6] | |||||

| 1995 | 942,000[58] | 2005 | 842,586[59] | 2015 | 2,345,666[5] | |||||

| 1996 | 1,275,000[60] | 2006 | 1,142,182[52] | 2016 | 2,200,000 (est.)[4] | |||||

| 1997 | 1,084,652[61] | 2007 | 969,561[52] | 2017 | ||||||

| 1998 | 1,229,445[62] | 2008 | 975,977[52] | 2018 | ||||||

| 1999 | 1,310,497[62] | 2009 | 876,453[52] | 2019 | ||||||

The 20th-century visitor record of 1,412,000 was reached in the year 1975.[50]

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Rijksmuseum was annually visited by 0.9 to 1.3 million people. On 7 December 2003, the main building of the museum was closed for a renovation until 13 April 2013. In the preceding decade, the number of visitors had slightly decreased to 0.8 to 1.1 million people. The museum says after the renovation, the museum's capacity is 1.5 to 2.0 million visitors annually.[3] Within eight months since the reopening in 2013, the museum was visited by 2 million people.[63]

The museum had 2.2 million visitors in 2013 and reached an all-time record of 2.47 million visitors in 2014.[6][16][59][52][51][55][56] The museum was the most visited museum in the Netherlands and the 19th most visited art museum in the world in 2013 and 2014.[7][8][16][64]

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of the museum from December 15, 2020, until June 4, 2021.[53]

Library

The Rijksmuseum Research Library is part of the Rijksmuseum, and is the best and the largest public art history research library in The Netherlands.

Restaurant

Rijks, stylized as RIJKS®, is a restaurant with 140 seats in the Philips Wing.[65] Joris Bijdendijk has been the chef de cuisine since the opening in 2014.[66] The restaurant was awarded a Michelin star in 2017.[67]

See also

- Onze Kunst van Heden – exhibition held in the winter of 1939 through 1940

Notes

- This includes the 16,777 visitors to the main building.

- In 1993, the visitors number had decreased with 23% to 936,400, i.e. there were approximately 1,216,103 visitors in 1992.

- The main building was closed from 7 December 2003.

- In 1995, the visitor number had decreased with 60,000 to 942,000, i.e. there were approximately 1,002,000 visitors in 1994.

References

- History of the Rijksmuseum, Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Address and route, Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- The renovation, Rijksmuseum. Retrieved on 4 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Jasper Piersma, "Van Gogh Museum zit Rijks op de hielen als populairste museum", Het Parool, 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Jaarverslag 2015 (in Dutch), Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Jaarverslag 2014 (in Dutch), Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- (in Dutch) Claudia Kammer & Daan van Lent, "Musea trokken dit jaar opnieuw meer bezoekers", NRC Handelsblad, 2014. Retrieved on 18 July 2015.

- Top 100 Art Museum Attendance, The Art Newspaper, 2015. Retrieved on 18 July 2015.

- Board of Directors, Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "The beginning". History of the Rijksmuseum. Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Ahmed, Shamim (10 July 2015). "Amsterdam • Venice of the North". theindependentbd.com. The Independent. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- Museumplein Archived 13 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, I Amsterdam. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "Rijksmuseum set for grand reopening in Amsterdam". BBC News. 4 April 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "The Rijksmuseum reopens: A new golden age". The Economist (London). 13 April 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- "The Dutch Prize Their Pedal Power, but a Sea of Bikes Swamps Their Capital". The New York Times. 20 June 2013.

- Jaarverslag 2013 (in Dutch), Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- "The changing picture of art of the Golden Age in the Rijksmuseum" in Netherlandish Art, 1600–1700. New Haven: Yale University Press 2000, 268–71

- (in Dutch) Roelof van Gelder, Schatkamer met veel gezichten, 2000. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- "To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, Tuesday, 28 January 1873". Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Stadhouderskade 42. Rijksmuseum (1876/85)". Monumenten en Archeologie in Amsterdam (in Dutch). City of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- "Stadhouderskade 42. Rijksmuseum (1876/85). Interieur". Monumenten en Archeologie in Amsterdam (in Dutch). City of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- A new art: photography in the 19th century. The photo collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, edited by curators Mattie Boom and Hans Rooseboom, preface by Peter Schatborn and Ronald de Leeuw, essays by Jan Piet Filedt Kok, Mattie Boom, Hans Rosenboom, Robbert van Venetie, Hedi Hegeman, Andreas Blühm, Saskia Asser and Annet Zondervan, Rijksmuseum & Van Gogh Museum, 1996, ISBN 90-5349-193-7

- "Final Design The New Rijksmuseum". The New Rijksmuseum. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- Jan Willem Pieneman Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- (in Dutch) Frederik Daniël Otto Obreen (1840–96) Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- (in Dutch) Jonkheer Barthold Willem Floris van Riemsdijk (1850–1942), Geheugen van Nederland. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) A.A.M. de Jong, Schmidt Degener, Frederik (1881–1941), Historici.nl, 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Th.J. Meijer, Röell, jhr. David Cornelis (1894–1961), Historici.nl, 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Lucette ter Borg, "Gedonderjaag in het Rijksmuseum", de Volkskrant, 2000. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Henk van Os". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "CV Prof. Dr. (h. c.) Ronald de Leeuw" (PDF). Kunsthistorisches Museum. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Charlotte Higgins (5 April 2013)."Rijksmuseum to reopen after dazzling refurbishment and rethink". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Taco Dibbits". Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- (in Dutch) Monumentnummer: 5680, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. Retrieved on 6 March 2014.

- "Rijksmuseum Revisited: The Dutch National Museum One Year on". 15 April 2014.

- "Rijksmuseum lanceert Rijksstudio". Creative Commons Nederland (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Rijkstudio promotes and enables the reuse of the Rijksmuseum collection.

- Nina Siegal (28 May 2013). "Masterworks for One and All". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- Erik Boekesteijn (12 April 2013). TWIL #94: Peter Gorgels (Internet Manager Rijksmuseum) (Video podcast). This Week In Libraries. Amsterdam: Shanachiemedia. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "For the First Time Ever, the Rijksmuseum Is Showing All 400 of Its Rembrandts at Once. Take a Look Inside the Momentous Exhibition". Artnet. 15 February 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Siegal, Nina (4 June 2021). "Telling Stories of Slavery, One Person at a Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "Slavery – Rijksmuseum". Rijksmuseum.nl. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "Rijksmuseum & Slavery – New light on the permanent collection". Rijksmuseum.nl. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "Slavery – 10 people, 10 stories". Rijksmuseum.nl. 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- "Trailer exhibition Slavery". Rijksmuseum.nl. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Sint Nicolaas, Eveline; Smeulders, Valika; Boom, Irma (2021). Slavery : the story of João, Wally, Oopjen, Paulus, van Bengalen, Surapati, Sapali, Tula, Dirk, Lohkay. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact. ISBN 978-90-450-4427-9. OCLC 1237644513.

- "Straks 28 Vermeers in het Rijksmuseum: 'Een echte once in a lifetime'". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Dutch). 31 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Jones, Jonathan (4 February 2023). "Vermeer will never look the same after Amsterdam exhibition". the Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- Bekker, Henk (3 February 2023). "Rijksmuseum – Largest Vermeer Exhibition Ever in Amsterdam in 2023". European Traveler. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- (in Dutch) Openingsjaar Rijksmuseum breek alle records Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Rijksmuseum, 2013. Retrieved on 2013-12-27.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 2001, Rijksmuseum, 2002. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 2011, Rijksmuseum, 2012. Retrieved on 25 April 2013.

- "RIJKSMUSEUM JAARVERSLAGEN" (PDF). RIJKSMUSEUM (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- (in Dutch) "Museumbezoek in 1993 sterk gedaald", NRC Handelsblad, 1994. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 2003, Rijksmuseum, 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Jaarverslag 2012 (in Dutch), Rijksmuseum. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- (in Dutch) "Nieuwe musea hadden in 1995 een goede start", de Volkskrant, 1996. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- (in Dutch) "Grote musea trokken in 1995 minder bezoekers", Trouw, 1996. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 2005, Rijksmuseum, 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Rijksmuseum en Kunsthal trekken veel bezoekers, de Volkskrant, 1997. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 1998, Rijksmuseum, 1999. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- (in Dutch) Jaarverslag 1999, Rijksmuseum, 2000. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Rijksmuseum welcomes two millionth visitor Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine (press release), Rijksmuseum, 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Top 100 Art Museum Attendance, The Art Newspaper, 2014. Retrieved on 28 June 2014.

- Brooke Bobb, "Go for the Art, Stay for the Food: The 7 Best Museum Restaurants Around the World Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine", Vogue, 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Joris Bijdendijk verantwoordelijk voor nieuwe restaurant Rijksmuseum", Het Parool, 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Michelinster voor Amsterdamse restaurants Rijks, Bolenius en Mos", Het Parool, 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

Further reading

External links

Media related to Rijksmuseum Amsterdam at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rijksmuseum Amsterdam at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Multimedia Content of museum

- Virtual tour of the Rijksmuseum provided by Google Arts & Culture