Ringette

Ringette is a non-contact winter team sport played on an ice rink using ice hockey skates, straight sticks with drag-tips, and a blue, rubber, pneumatic ring designed for use on ice surfaces.[3] While the sport was originally created exclusively for female competitors, it has expanded to now include participants of all gender identities.[4] Although ringette looks ice hockey-like and is played on ice hockey rinks, the sport has its own lines and markings, and its offensive and defensive play bear a closer resemblance to lacrosse or basketball.[5]

Women playing ringette in Canada's National Ringette League (NRL) | |

| Highest governing body | International Ringette Federation (IRF) |

|---|---|

| First played | 1963 |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No contact, incidental only |

| Team members |

|

| Type | Female winter team sport |

| Equipment | Ringette ring, ringette stick, ice hockey skates, ringette girdle with pelvic protector and other protective gear |

| Venue | Standard Canadian ice hockey rink with ringette markings |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | No[1][2] |

| Paralympic | No |

| World Games | No |

The sport was created in Canada in 1963 by Sam Jacks from North Bay, Ontario, and Red McCarthy from Espanola, Ontario. Since then, it has gained popularity to the point where, in 2018, more than 50,000 individuals, including coaches, officials, volunteers, and over 30,000 players, registered to take part in the sport in Canada alone.[6][7] The sport has continued to grow and has spread to other countries including the United Arab Emirates.[8] Two different floor variants of ringette are also played: in-line ringette, and gym ringette.[9][10][11]

Ringette is especially popular in Canada and Finland, having come to prominence as national pastimes in both countries. The premier international competition for ringette is the World Ringette Championships (WRC) which is organized by the International Ringette Federation (IRF). On the international stage, Canadian teams and Finnish teams have proved to be the most successful and are regularly at the top of the rankings. Several other countries currently organize and compete in the sport including Sweden, the United States, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, all of whom have national ringette teams though Slovakia has not competed since the 2016 World Ringette Championships. National organizations for the sport include Ringette Canada, Ringette Finland, the Sweden Ringette Association, USA Ringette, the Czech Ringette Association, and the Slovakia Ringette Association.

The sport is also played at the semi-professional level in Canada (National Ringette League), in Finland (SM–Ringette), and in Sweden (Ringette Dam-SM), as well as the university and college level. In Canada, the sport is a part of the Canada Winter Games programme and the annual Canadian Ringette Championships serve as the country's premiere competition for the sport's elite amateur athletes. The sport's first international tournament was hosted in Finland in 1986.[12][13]

Play

Two teams compete against each other on an ice rink whilst wearing ice hockey skates and using other ringette-specific equipment. The objective is to score more goals than the opposing team by shooting a blue, hollow, rubber ring into the opponent's goal net. Skaters use a long straight stick with a tapered end and a drag-tip. Ringette Canada creates the "Official Rules and Case Book of Ringette" for participating parties competing in Canada; it contains the forms, rules, and codes which are used in the sport nationwide.[14]

Intentional body contact is not allowed in ringette, though incidental contact may occur. Body checking and boarding are penalized and fighting is strictly forbidden by a zero-tolerance policy. The only type of checks allowed are stick checks, which involve using the stick in an upward sweeping motion to knock the ring away from the ring carrier or by raising the ring carrier's stick upwards by lifting or knocking it, followed immediately by an attempt to steal the ring. Sticks may not be raised above shoulder height and high-sticking is penalized.[15][16][17]

In ringette, teams during play are divided into two units of six players: one centre, two forwards, two defenders, and one goaltender.[18] The players take up specific formations and roles when defending or attacking. The goal of the game is to score more goals than the opposing team by shooting the ring into the opposing team's net. Goal nets used in ringette are identical to those used in ice hockey (6 by 4 feet [1.8 m × 1.2 m]). Ringette goaltenders are the only players allowed to play the ring with their hands but must do so from within their goal crease which only they can enter. After stopping a shot on net or receiving a pass, they have five seconds to throw, push or pass the ring to another player.

In comparison to ice hockey, the rules of ringette differ in several ways. There are no offsides, or icing. Ringette games are typically played on ice surfaces used for playing ice hockey but use different lines and markings; a ringette rink is augmented with lines and markings specific to ringette instead. Ice hockey rink markings such as hash marks and face-off dots are not used in ringette. In addition, a ringette rink uses extra lines and markings such as the "free play line" a.k.a. as the "extended zone line".

When attempting to gain possession of the ring, ringette's blue line rule prohibits players from carrying the ring over either of the blue lines bisecting the ice surface and players are thus required pass the ring over each individual line to another teammate to advance the play. In addition, only the goaltender may enter the goaltenders crease, and before each play a free pass is taken in which no one but the player taking the free pass is allowed inside the free pass circle. Once the free pass has been taken and the ring is completely outside of the circle, the other players are allowed to enter the area again.

Recreationally, ringette is a game played over two 24-minute intervals. At the sport's top levels, specifically the National Ringette League and World Ringette Championships, the game is divided into four quarters, with each quarter lasting 13 minutes.[19] A 30-second shot clock is used to prevent players from running out the clock, improve the flow of the game and increase the speed of play. The rule was first introduced in Canada in 2002 and went into effect for age groups which used to be known as the junior, belle, and open divisions.[20] The 30-second shot clock is now used almost universally in all age groups as well as internationally (including the World Ringette Championships) with the exception of very young players and some of the lower divisions. If the shot clock goes off during the play, the goaltender gets the ring.

The ringette rink uses five free pass circles, each of which has a bisecting line. The start of every quarter begins with a free pass from the free pass circle at centre ice. During the rest of a game, free pass circles are used for restarting the game after a goal or a violation. At such times, players may not enter the circle unless they are the player making the free pass. If a player is making a free pass, they have five seconds after the whistle blows to either pass the ring to another teammate or take a shot at the opposing team's goal, but they must not exit the circle or cross the bisecting line before doing so.

The sport uses a "free play zone" (alternatively known as the "extended zone") which exists in each of the rink's two end zones and consists of the area between the end boards and the free play line (or "ringette line"). The ringette line is a thin red line bisecting the rink which is placed atop of the free pass circles in the end zone. Only three players from each team are allowed in these zones at one time or a "four in" call is made and play is stopped with a free pass awarded to the non-offending team. The remaining players must remain behind the ringette line. There is one exception which can be made in higher divisions whereby the defending team is serving a penalty: in such a case, the opposing team may pull its goaltender and send in another attacker, meaning four of its players are allowed into the zone without penalty.

Ringette rink

Ringette games are played on ice rinks either indoors or outdoors. Playing area, size, lines and markings for the standard Canadian ringette rink are similar to the average 85-by-200-foot (26 m × 61 m) Canadian ice hockey rink with certain modifications.[21][22][23][24] An exception exists for European ice hockey rinks which may be slightly larger in size. A ringette rink uses most (but not all) of the standard ice hockey markings used by Hockey Canada but with additional markings: five free pass circles (each with a bisecting line) with two in each end zone and one at centre ice, four free-pass dots in each of the end zones, two free-pass dots in the centre zone, and a line demarcating a larger goal crease area which is shaped in a semi-circular fashion. Two additional free-play lines (also known as a "ringette line" or "extended zone line") are also required, with one in each end zone.

Equipment

Ringette uses a blue, rubber, pneumatic ring designed for play on an ice surface. The official ring has a diameter of 16.5 cm.

Ringette rings have three designs: the official ice ring designed for use on ice, a practice ring, also designed for use on ice known as a "Turbo ring", and the gym ring, designed for use on dry floors for gym ringette.

The ring used for the ice game is a blue, rubber pneumatic torus. The gym ringette ring is an orange torus made of a sponge-like material and unlike the ice ring, is not hollow. The ringette "practice ring" (a.k.a. "turbo ring")[25] is not a torus, but a small open disk (a toroid) used on ice to help ringette players develop and hone pass receiving skills and is typically either orange or blue. First designed in Canada in 1997, the Turbo ring is safe to use when shooting on goalies, doesn't break, and slides like an official ice ring but is half the size. Practice rings don't collect snow and come in different high-optic colours for easy visibility.

The equipment players wear is similar to that used by ice hockey players but involves a few differences. Required equipment for ringette players includes the following:

- ringette stick (or goal stick for goaltenders)

- ice hockey skates (or ice hockey goalie skates for goaltenders)

- shin pads (or goalie pads)

- protective girdle (or hockey shorts for goaltenders)

- pelvic protector (a jill or jockstrap)

- ankle-length ringette pants

- ringette or ice hockey gloves

- elbow pads

- jersey

- helmet with ringette facemask (must meet specific regulations)

- neck guard (must meet specific regulations)

- shoulder pads - mandatory for most players up to the junior level (14-15), then the players can decide whether they wish to wear them or not

Ringette sticks[26] are straight and have tapered ends with metal or plastic drag-tips designed with grooves to increase the lift and velocity of the wrist shot. Sticks must conform to specific rules including those which determine the acceptable measurements for the taper and face of the stick. The stick and the tip must also meet the minimum width measurements. Sticks are reinforced to withstand the bodyweight of a player - a ring carrier leans heavily on the stick to prevent opposing players from removing the ring.

Ringette facemasks are designed to meet ringette's specific safety requirements and are available in different styles for both goaltenders and other players. In the case of the traditional wire cage ringette masks in North America, the bars are shaped like triangles rather than squares and are designed so that the end of a ringette stick cannot enter the mask. Similar North American designs exist but must meet certain safety specifications required by the CSA Group (formerly the Canadian Standards Association or "CSA"). European ringette cage and bar styles may differ. Some players wear clear plastic shields but half-visors are illegal. Some masks are a combination of a shield and tightly spaced wires or similar. At all levels, ringette players must wear a pelvic protector.

Goaltenders

Goalies in ringette now use equipment that is mostly interchangeable with that used in ice hockey. While ice hockey goaltending equipment is used, there are a few differences. For example, goalies in ringette must wear leg pads resembling those used in ice hockey and use the same goalie skates and goalie stick as goalies in hockey. Nonetheless, goalies are required to wear a combination of a ringette-approved helmet, facemask, and throat protector. Moreover, they must also wear genital protection, chest and arm protector, and pants.

On the free hand, also known as the glove side, a glove known as a "catcher" or simply a "glove" is worn. For their glove side, goaltenders may use an ice hockey trapper, an ice hockey blocker, or a ringette goalie trapper a.k.a. "Keely glove", named after a Keely Brown, a former goalie of Canada's national ringette team who helped create the sport's first design.[27][28] A custom prosthetic Keely glove design has been developed for a one-handed goalie.[29][30]

Variants

There are two off-ice variants of ringette: in-line ringette and gym ringette, played wearing shoes. Gym ringette was developed in Canada as a floor variant of ringette in the 1990s, largely by Ringette Canada.[9][10] It is meant to be played as a stand-alone activity or as a form of dry-land training to help players develop skills which are transferable to the ice sport.[11] In-line ringette is played as an informal alternative, but a consistent set formal rules have not been codified and sizeable organizing bodies do not exist. Ringette does not have any parasport variant.

History

Development

Ringette was created in Northern Ontario, Canada, as a civic recreation project for girls by its two founders,[31] Sam Jacks from North Bay, Ontario, and Red McCarthy from Espanola, Ontario.[32][33] Jacks is credited with creating the idea for the sport in 1963, following his earlier development of a variant of floor hockey[34] in 1936,[35][36] which used bladeless sticks and a flat felt disk with a hole in the centre.[37] McCarthy was responsible for developing the sport's first rules.[38] Ringette was created in the hopes of increasing and maintaining female participation in winter sport under the existing authority of the Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (SDMRO) and the Northern Ontario Recreation Directors Association (NORDA) due to a lack of success in generating interest among the young female population in the winter team sports of girls' broomball and girls' ice hockey.[33][34]

For as long as Municipal Recreation has existed there has been, with some justification, a concern that our sports tended to be male orientated.

Over the years attempts have been made to discover or create a new winter court or rink game for girls. Broomball was such a game, and for some time girls' Ice Hockey had a certain success. Neither of these games seemed to have the acceptance of the female population as indicated by lack of growth.

Ringette is a new attempt to provide a winter team sport, on skates, for girls.[33]

— Ringette Rules (A Game on Skates for Girls), SDMRO (1965–1966)

The idea for the new game was first introduced at a general meeting between the members of NORDA in January 1963 in Sudbury, Ontario.[39][38] The first ringette game took place that fall in Espanola, Ontario under the direction of McCarthy between a group of girls who had played ice hockey at Espanola High School.[40][38] Other Northern Ontario communities soon began experimenting with the game in the winter of 1964–65.[33][41] On May 31, 1965, a set of rules developed by McCarthy were presented by NORDA to the SDMRO which then published them for use in the 1965–66 season.[33][42][43][44][45][46]

The SDMRO then developed and organized the sport on a larger scale, and in 1969 the Ontario Ringette Association (now Ringette Ontario) became the first provincial ringette association in history[12][13] and was formed as a provincial governing body with a $229.27 provincial government grant and 1,500 players in 14 locations.[47][48]

The sport was introduced to Manitoba in 1967 and the province's first team, the Wildwood, was created two years later in Fort Garry, Winnipeg.[20][49][50]

Growth

In Canada, ringette spread to Manitoba, Quebec, Nova Scotia and British Columbia.[20] To better organize the sport nationally, Ringette Canada was founded in 1974. The following year, the sport received national television exposure in an intermission feature during Hockey Night in Canada.[20] The copyright to the official ringette rules, which had been transferred from the SDMRO to the Ontario Ringette Association in 1973, was acquired by Ringette Canada in 1983.

After Jacks died in May 1975, his wife Agnes Jacks promoted the game and acted as an ambassador for the sport until her own death in April 2005. She received the Order of Canada for this work in 2002.[51] Ringette Canada initially had little money and received no assistance from the Canadian federal government though the sport grew significantly between the 1970s and 1980s.[52]

In 1979, former professional Finnish ice hockey player and coach Juhani Wahlsten introduced ringette to Finland at girls ice hockey practices in the Turku area. The first recorded game in Finland took place on January 23, 1979, and the first tournament took place in early 1980. Meanwhile, Alpo Lindström and his son Jan Lindström[53] brought ringette to Naantali near the end of 1979, the same year Juhani Wahlsten brought the sport to Finland for the first time.[54] Jan had been an exchange student in the United States the previous year, 1978, and had seen girls playing ringette. When he returned to Finland, he founded VG-62's ringette club, VG-62 (ringette).[55]

The game quickly gained popularity, aided by Canadian coaches who helped establish programs. In 1983, a national association was established, which organized tournaments of more than a hundred matches by the mid-1980s.[56]

Ringette spread to Sweden in the early 1980s. The league Ringette Dam-SM was formed in 1994, along with the Sweden Ringette Association was also established in 1994.[57][58][59]

Ringette was introduced to the Midwestern United States in the mid-1970s and had gained popularity by the 1980s with most activity centred in Minnesota. However, participation fell dramatically in the mid-1990s when ice hockey was endorsed over ringette as an official high school sport for girls.[60]

In 1986, the World Ringette Council was founded in Finland to promote and develop the sport internationally and to establish international competitions. The World Ringette Championships were first held in 1990. The following year, the World Ringette Council changed its name to the International Ringette Federation (IRF), possibly to avoid confusion due to the fact that it had the same acronym as the world event.[61]

International governance

The International Ringette Federation (IRF) is the highest governing body for the sport of ringette.[62] There are four member countries: Canada, Finland, the USA, and Sweden. Historically, Canada and Finland have been the most active ambassadors in the international federation and regularly send teams to demonstrate how ringette is played in countries including Japan, Australia, Iceland, and New Zealand, Norway, Slovakia, and South Korea.

Olympic status

Ringette is not a part of the Winter Olympic programme.[1][2] The International Olympic Committee (IOC) asked Canada to stage a heritage games event for the sports of ringette, broomball, and lacrosse for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, but the three sports were unable to meet objectives and the event failed to materialize.[63] Because ringette has not obtained Olympic status, the sport does not receive federal financing in Canada.[64]

World Ringette Championships

The World Ringette Championships (WRC) is the premier international ringette competition between ringette-playing nations, organized by the IRF. Initially held in alternate years, the tournament has been held every two to three years since the 2004 edition with some exceptions. The winning national senior team is awarded the Sam Jacks Trophy. The winning national junior team is awarded the Juuso Wahlsten Trophy. The President's Trophy is awarded to the winner of the President's Pool.

Ringette World Club Championship

Initially organized by the International Ringette Federation as a separate tournament from the World Ringette Championships, the Ringette World Club Championship was a competition held in 2008 and 2011, which featured the best teams from the Canadian National Ringette League, the national Finnish ringette league, SM Ringette, (formerly Ringeten SM-sarja), and Sweden's, Ringette Dam-SM. The championship was discontinued after 2011 due to the fact that competing teams faced financial costs which made the tournament untenable.

Czech Lions Cup

Traditionally held in Prague, the Czech Lions Cup is the only ringette tournament of its kind in Central Europe. Along with the Finland Lions Cup, it is one of Europe's premier ringette tournaments played every summer.[65]

Finland Lions Cup

The Finland Lions Cup is a ringette tournament which takes place annually in Finland.[65] Along with the Czech Ringette Challenge Cup, it is one of Europe's premier ringette tournaments played every April, July, and December.[66] The tournament typically features ringette teams from Finland, Sweden, and Canada. Competing divisions include under-14 (U14), under-16 (U16), and under-19/open.

Ringette by country

Canada

Ringette is played in all ten Canadian provinces and the Northwest Territories. An average of 30,000 players register to play the sport annually.[7] Ringette Canada is the country's national organizing body and promotes the sport. It established the Ringette Canada Hall of Fame in 1988.[67][68]

Canada selects two national ringette teams for international competition: Team Canada Junior and Team Canada Senior. Both teams compete in the World Ringette Championships. At the university and college level, ringette players have the opportunity to play their sport in several provinces. The National Ringette League[69] (NRL) is Canada's semi-professional ringette league for elite ringette players aged 18 and over.

Canada's elite ringette players compete in the annual Canadian Ringette Championships. There are championships for under-16 years, under-19 years, and the National Ringette League (the Open division prior to 2008).

Ringette became a part of the Canada Winter Games program in 1991.[70][71] The sport is also part of the provincial, winter-based, multi-sport competitions in some provinces. Several cities and regions also have annual ringette competitions.

Cross-sport participation is common among Canada's ringette athletes, with some national-level ringette players having also played bandy for the Canadian women's national bandy team.[72][73][74][75]

Finland

There are more than 10,000 ringette players registered to play in Finland.[76] Players participate in 31 ringette clubs, with important clubs in Naantali, Turku, and Uusikaupunki.[77] The national governing body for the sport, Ringette Finland, was created in 1983, four years after Juhani Wahlsten, also known as "Juuso" Wahlsten, introduced ringette in Finland; he is considered the "Father of Ringette" in the country.[78] Former President of Ringette Canada, Barry Mattern, helped introduce ringette to Finland in 1979 when he brought a team over from Winnipeg, Manitoba's, North End.[79]

The Finland national ringette team competes on a regular basis at the World Ringette Championships is home to both Team Finland Senior and Team Finland Junior.

Finland has a semi-professional ringette league called SM Ringette, formerly known as Ringeten SM-sarja.[80][81][82] In english it is known as the Finnish National Ringette League. The league has been in operation since the 1987–88 winter season. The Agnes Jacks Trophy, named after the wife of Sam Jacks, is awarded to the league's Most Valuable Player at the end of the each season and was first awarded in 1992.[83]

The Women's Premier League was formerly known as Ringete ykkössarja. The first division has been played since the 2008 season. During the 2021–22 season, six teams played in the Women's First Division.

Naisten Ykkössarja (Women's Premier League) is the second-highest series level of Finnish Ringette, which operates under Ringette Finland (Suomen Ringetteliitto), formerly known as the Finnish Ringette Association)

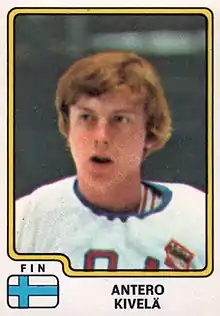

Also notable is Timo Himberg who coached the Finland national ringette team for many years, and Antero Kivelä who coached in the SM ringette league for over a decade.

Sweden

Ringette was introduced to Sweden in the 1980s.[84][85] The first ringette club was Ulriksdals, in Solna, Stockholm, with most Swedish ringette associations located in the surrounding Mälardalen region.[84][58] There are programs of twin towns between the Sweden Ringette Association and Canadian associations for the development of the sport within the Swedish population. In Sweden more than 6,000 girls are registered to play ringette each year.[85]

Sweden's elite league (Ringetteförbundet) was established in 1994 and the Sweden Ringette Association was formed the same year.[58] Several junior teams and numerous amateur teams are connected with these 7 semi-pro clubs. The league groups together seven semi-professional women's clubs: Kista Hockey,[86] IFK Salem,[87] IK Huge,[88] Järna SK,[89] Segeltorps IF,[90] Sollentuna HC,[91] and Ulriksdals SK.[92]

The Swedish Ringette Association is now an associate member of the Swedish Sports Confederation.[59] The Sweden national ringette team competes regularly at the World Ringette Championships in the Senior Pool. Sweden has occasionally formed a junior national ringette team, but the senior team has made the most international appearances.

United States

The two national sporting organizations for ringette in the United States are USA Ringette[93] and Team USA Ringette.[94][95] The sport was introduced in the Midwestern US in various places during the mid-1970s and ten U.S. States were home to ringette by the early 1970s.[96] During the 70's ringette was most popular in Alpena, Flint, Michigan, Minnesota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, and Viroqua and Onalaska, Wisconsin.[97]

The United States national ringette team competes regularly at the WRC, beginning in 1990 with the first WRC. Notable in the success of Team USA's development is coach Phyllis Sadoway who was the team's head coach at the WRC from 2004 to 2013, and was inducted as a coach into the Ringette Canada Hall of Fame in 2012.[98][99]

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is host to an annual international ringette tournament in Europe, the Czech Ringette Challenge Cup and the Czech Republic national ringette team competes in the World Ringette Championships. The Czech Republic made its first international appearance at the 2016 World Ringette Championships. It was also host of the first ever World Junior Ringette Championships (Under-19) in Prague in 2009. The national governing body for ringette in the country is the Czech Ringette Association.

Japan

In 1982 ringette was introduced in Japan by former Ringette Canada President, Barry Mattern.[12]

Australia and New Zealand

In 1986 ringette was introduced to Australia and New Zealand via the "Maples Ringette tour".[12]

Soviet Union

In 1984, a sports delegation helped introduce ringette to the U.S.S.R. In 1985 ringette was again introduced via an initiative called 'Ringette in Russia' by the St. James Ringette Association of Winnipeg, Manitoba. However, within two years it became evident that the sport had failed to take hold in the Soviet Union.[100][12]

Other countries

The international development of the sport has continued with the formation of associations in Estonia, Slovakia, and France. Furthermore, Ringette Canada has been instrumental in spreading the game to the Netherlands, Switzerland, and West Germany.[101] The sport has also been introduced to South Africa[96] and the United Arab Emirates.[8][102]

Impact

Ice hockey

Ringette has had an unintentional influence on the sport of ice hockey, including a minor effect on men's professional ice hockey and a larger impact on girls' and women's ice hockey.

The "ringette line" began to have a potential impact on men's professional ice hockey in 2012 in regards to the American Hockey League with several professionals including Toronto Maple Leafs general manager Brian Burke considering its possible application in ice hockey to correct areas of concern about the game.[103]

Ringette concepts and rings have been used in professional ice hockey practices from the late 1970s, when the Toronto Maple Leafs head coach Roger Neilson sought to add variation to practices.[104] After observing this, the coach of the Czechoslovakia men's national ice hockey team, Karel Gut, took notes on the game and made modifications to apply it to a training system used in Czechoslovakia's university ice hockey teams.

Prior to the 1990s in Canada, the development of women's ice hockey had failed and growth stagnated. In Ontario where ringette was invented, there were only 101 female ice hockey teams existing in the province by 1976.[105] By 1983, there were over 14,500 ringette players in Canada compared to only 5,379 female ice hockey players.[106] By 1990–91 there were still only 8,146.[107] Female ice hockey only began to experience significant growth after it banned body checking, which was mostly accomplished in Canada by 1986.[106] Following this, the expansion of female ice hockey in Canada was largely accomplished by aggressive recruiting from the ringette system.[106]

Culture

Ringette remains one of the few organized sports worldwide where all of its elite athletes are female rather than male. Many women's sports are variants of male-dominated sports and are meant to serve as the female equivalent, rather than being sports developed for females. Canadian media and parts of the ringette community increasingly avoid calling ringette a girls' sport in spite of its heritage.[33][108] Although mixed teams have appeared, some have claimed that there is a social stigma against males playing ringette.[109][110] In 2021, CBC Radio reported on the controversy of a teenage ringette goaltender who identified as male and who had competed in ringette in Quebec.[111]

Popular culture

Canada Post issued four stamps in a series of sports with Canadian origins: ringette, basketball, five-pin bowling and lacrosse.[112][113] The commemorative stamps were issued on August 10, 2009, and featured well-worn equipment used in each sport with a background line drawing of the appropriate playing surface.

The sport was featured on an episode of the children's show Caillou.

Notables

Finland

- Susanna Tapani

- Anna Vanhatalo

- Salla Kyhälä

- Marjukka Virta

- Anne Pohjola

- Katja Kortesoja

- Petra Ojaranta

- Riikka Häyrinen

- Kirsi Pukkila

- Petra Vaarakallio – a national team member who stopped playing after receiving a six-month suspension for kicking a fallen opponent

- Emma-Julia Wood

Canada

- Keely Brown (goaltender)

- Shelly Hruska[114][115]

- Julie Blanchette

- Stéphanie Séguin

- Erin Cumpstone

- Jennifer Hartley

- Judy Diduck - member of the first Canadian ringette team to win the World Ringette Championships in 1990

Others

Notable in ringette is Sam Jacks who created the sport, in addition with the help of Red McCarthy. Juhani Wahlsten is notable for introducing ringette to Finland in the late 1970s. Timo Himberg coached Finland's national teams for many years and Antero Kivelä coached semi-pro SM Ringette.

Gallery

Julie Blanchette, former Team Canada player

Julie Blanchette, former Team Canada player Stéphanie Séguin, former Team Canada player

Stéphanie Séguin, former Team Canada player

Antero Simo Tapani Kivelä, former Team Finland ice hockey goalie; coached in Finland's semi-pro ringette league, Ringeten SM-sarja, now called "SM Ringette"

Antero Simo Tapani Kivelä, former Team Finland ice hockey goalie; coached in Finland's semi-pro ringette league, Ringeten SM-sarja, now called "SM Ringette"

See also

Further reading

- Collins, Kenneth Stewart (2004). The Ring Starts Here: An Illustrated History of Ringette.

- Hall, Margaret Ann (2016). The Girl and the Game: A History of Women's Sport in Canada. University of Toronto Press.

- Hall, Margaret Ann; Pfister, Gertrud. Honoring the Legacy: Fifty Years of the International Association of Physical Education and Sport for Girls and Women.

References

- "Why isn't ringette in the Olympics?". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Butler, Nick (4 February 2018). "New sports face struggle to be added to Winter Olympic Games programme, IOC warn". Insidethegames.biz. Dunsar Media. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Maxymiw, Anna (4 November 2014). "Girls on Ice". The Walrus. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- "Trans-Inclusion Policy and Resources". Ringette Canada. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- Allison Lawlor (19 April 2005). "Obituaries, AGNES JACKS, RINGETTE PROMOTER 1923-2005". ringettemanitoba.ca. The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "About Ringette". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- "Ringette Canada reaches record registration numbers, announces new president and board appointments". www.ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 7 November 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Pennington, Roberta (3 October 2014). "Ice game hit with desert youngsters". thenationalnews.com. The National News.

- "Gym Ringette: Instructor Guide" (PDF). Ringette Canada. Ringette Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2017.

- Veale, Beth (1995). Gym Ringette: Basic skills series. Google Books: Ringette Canada.

- "Gym Ringette - Ontario Ringette Association". ringetteontario.com. Ringette Ontario. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- "The History of Ringette". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2000. Archived from the original on 2 March 2000. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- "Our Sport | History of Ringette". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- "Official Rules and Case Book of Ringette" (PDF). ringettealberta.com. Ringette Canada. 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "Girls suffer sports concussions at a higher rate than boys. Why is that overlooked?". Washington Post. 10 February 2015.

- Mac Shneider (14 February 2018). "Why women's ice hockey has a higher concussion rate than football". Vox. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- Sanderson, Katharine (3 August 2021). "Why sports concussions are worse for women". Nature. 596 (7870): 26–28. Bibcode:2021Natur.596...26S. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02089-2. PMID 34345049. S2CID 236915619.

- "The Rules of Ringette". National Ringette School. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "What is RINGETTE". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "History of Ringette". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- "Ringette Canada Line Markings" (PDF). Canadian Recreation Facilities Council. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- "Rink Line Markings Ringette". BC Ringette Association. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- "Ringette Canada Line Markings Ontario". Ontario Recreation Facilities Association, Inc. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- "Rink Markings". Prince George Ringette. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- "A passing problem | The Story of the Mini Turbo ring". ringettestore.com. The Ringette Store. 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Ringette sticks". Shopify.

- "What's In a Name? Inventing the Ringette Goalie Trapper". ringettestore.com. The Ringette Store. 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- "World Champion Keely Brown Launches Innovative Ringette Goalie Trapper". newswire.ca. 30 November 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Bailey Nitti (18 December 2022). "Prosthetic glove, determination help Alberta teen excel as ringette goalie". edmonton.citynews.ca. Edmonton City News. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- Emily Senger (19 February 2023). "Meet the one-handed goalie stopping shots with a custom glove". cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/. CBC News. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Ringette, Canada. "Founders of Ringette". Ringette Canada Hall of Fame.

- "History of ringette". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- "Ringette (A Game on Skates for Girls) Rules 1965-66". Ringette Calgary. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario/Ringette Canada.

- "North Bay Sports Hall of Fame Inductee".

- "Sam Jacks – Ringette Canada". ringette.ca. Ringette Canada. 2017. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- "Hall of Famer, Sam Jacks". sportshall.ca. Canada's Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Academic Edition, s.v. "Ice Hockey"

- Mayer, Norm (1989). "The origins of ringette, Espanola's McCarthy developed the game". The Sudbury Star.

- Collins, Kenneth S. (2004). The Ring Starts Here: An Illustrated History of Ringette. Cobalt, Ontario: Highway Book Shop. p. 2. ISBN 0-88954-438-7.

- "Canada (2009) Sc. # 2338 CANADIAN SPORTS INVENTIONS XF FDC". ebay.com. Canada Post. 2009. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022.

- North Bay Nugget. January 23, 1965. p. 8.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (1964–65). "Rules Ringette (A GAME ON SKATES FOR GIRLS) 1965–66". ringettecalgary.ca. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (1964–65). "Rules Ringette (A GAME ON SKATES FOR GIRLS) 1965–66". ringettecalgary.ca. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (1964–65). "Rules Ringette (A GAME ON SKATES FOR GIRLS) 1965–66". ringettecalgary.ca. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (1964–65). "Rules Ringette (A GAME ON SKATES FOR GIRLS) 1965–66". ringettecalgary.ca. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario (1964–65). "Rules Ringette (A GAME ON SKATES FOR GIRLS) 1965–66". ringettecalgary.ca. Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- "History of ringette".

- Allison Lawlor (19 April 2005). "Obituaries, AGNES JACKS, RINGETTE PROMOTER 1923-2005". ringettemanitoba.ca. The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Manitoba's First Ringette Team". ringettemanitoba.ca. Ringette Manitoba. 14 December 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- "1969 Wildwood Team | (1st Ringette Team in Mb.)". ringettemanitoba.ca. Ringette Manitoba. 1969. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- "Impact of Immigration on Sports, Sam and Agnes Jacks". Ontario Heritage Trust, heritagetrust.on.ca. 27 February 2017.

- Jim Timlick (17 March 1991). "The Godfather of ringette". Winnipeg Free Press Weekly. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Jan Lindström (23 August 2021). "In Memoriam: Alpo Lindström | Naantalin Mr. Ringette Alpo Lindström on poissa" [In Memoriam: Alpo Lindström | Naantali's Mr. Ringette Alpo Lindström is gone]. ringette.tablettilehti.fi (in Finnish). Ringette Tablettilehti. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- "Alpo Lindström toi poikansa Janin kanssa ringeten Naantaliin v. 1979 ja perusti VG-62:n ringettejaoston" [Alpo Lindström brought Ringette to Naantali with his son Jan in 1979 and founded VG-62's ringette division.]. facebook.com (in Finnish). VG–62 Ringette. 6 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "VG_ringette_uusi.JPG". ringette.skrl.fi/. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- "Ringette Suomessa" [Ringette in Finland]. Wrc2015.com (in Finnish). Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- "Svenska Ringetteforbundet" [The Swedish Ringette Association | History]. www.sweringette.se. Sweden Ringette Association. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- "Svenska Ringetteförbundet" [Sweden Ringette Association] (in Swedish).

- "Historia och organisation - Uppslagsverk - NE.se". ne.se.

- "The History of USA Ringette & Team USA". Ringette Team USA. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- "IRF History".

- "IRF". IRF.

- Martin Cleary (1 December 2011). "An Olympic dream lives on with broomball worlds coming to Ottawa Valley" – via PressReader.

- Smith, Beverely (27 November 2002). "Canada out to ring up gold metal". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "CZECH LIONS RINGETTE CUP 2023". lionscup.fi. 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- "Ringette – Pelimatkat Sports Travel". pelimatkat.com. 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- "Hall of Fame".

- "Ringette History – National Ringette School".

- "National Ringette League". nationalringetteleague.ca.

- "Canada Winter Games".

- "Canada Games". Canada Games.

- "USA Women's Bandy vs Canada". February 20, 2016 – via Flickr.

- "Winnipeg-based national women's bandy team wins North American crown". winnipegsun.

- "National Ringette League Nash a triple threat | NRL". January 9, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-01-09.

- Wynn, Thom (December 27, 2012). "USA to Host Canada in Women's Bandy". USA Bandy.

- "Ringette History". IRF.

- "Etusivu - Suomen Ringetteliitto Ry". ringette.fi.

- "History". Archived from the original on September 7, 2011.

- T. Kent Morgan (26 November 2013). "Celebrating 50 years of ringette in Canada". winnipegfreepress.com. Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- "Etusivu - SM RINGETTE - Suomen Ringetteliitto". www-smringette-fi.translate.goog.

- "Etusivu - SM RINGETTE - Suomen Ringetteliitto". smringette.fi.

- "Ringeten SM-Sarja Website". Archived from the original on September 7, 2011.

- "AGNES JACKS -TROPHY | SM-sarjan arvokkain pelaaja". smringette.fi (in Finnish). SM Ringette. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- "Svenska Ringetteförbundet". sweringette.se (in Swedish). Sweden Ringette Association. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Sidan inaktiv - Sidan är ej betald". lagsidan.se. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- "Kista Ringette U/J | laget.se". laget.se.

- "IFK Salem | laget.se". laget.se.

- "Sidan du sökte finns inte längre". rf.se.

- (in Swedish) Järna SK Archived 2018-11-16 at the Wayback Machine

- "Segeltorps Idrottsförening". segeltorpsif.se.

- "Sollentuna HC". sollentunahockey.com.

- "Sidan inaktiv - Sidan är ej betald". lagsidan.se. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- "Welcome to usaringette.org". usaringette.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Team USA Ringette". teamusaringette.com.

- "Team USA Ringette". teamusaringette.com. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "This World-Famous Winter Sport Was Invented In North Bay, Ontario". www.northernontario.travel. 26 January 2023.

- "Team USA Ringette". teamusaringette.com.

- "Phyllis Sadoway: The Godmother of Ringette Just Keeps Skating - SWSCD". seewhatshecando.com.

- "Phyllis Sadoway". 28 April 2015.

- Jim Timlick (17 March 1991). "The Godfather of ringette". Winnipeg Free Press Weekly. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- "Metcalfe and District Ringette Association | History of Ringette". members.storm.ca.

- Pennington, Roberta (3 October 2014). "Ice game hit with desert youngsters". thenationalnews.com. The National News. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- Klein, Jeff (3 March 2012). "The Red Line and the Ringette Line: What's the Difference?". The New York Times.

- Lawlor, Allison (2005). "Obituaries: Agnes Jacks, ringette promoter 1923–2005". The Globe and Mail.

- Galt, Julia (28 February 2020). "Newmarket author reveals untold stories of women's hockey history". Newmarket Today.ca. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Etue, Elizabeth; Williams, Megan (11 September 1996). On the Edge: Women Making Hockey History. Second Story Press. ISBN 9780929005799.

- "Hockey Canada | Statistics & History". hockeycanada.ca. Hockey Canada. 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Lori Ewing (18 February 2019). "Canada Winter Games using new gender inclusion policy at 2019 event". CBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Hooking kids into ringette proves challenging: Organizers say there's still a 'girls only' stigma attached to the sport". CBC News. 31 October 2011.

- "Prince George U-16 Ringette Team Breaking Stigmas". CKPGTV Today. 23 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13 – via YouTube.

- Ore, Jonathon (22 January 2021). "The Doc Project: This teen was a celebrated ringette goalie in Quebec until the league learned he was transgender". CBC Radio.

- "Ringette - Canadian Inventions: Sports". postagestampguide.com. Postage Stamp Guide.

- Canada Post Stamp Details, Volume XVIII, No. 3. July–September 2009. p. 18.

- "2002 World Ringette Championship Team". 28 April 2015.

- Forsyth, J., & Giles, A.R. (Eds.). (2013). Aboriginal Peoples & Sport in Canada: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Issues. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

External links

- Ringette Canada

- (in Finnish) Ringette Finland

- Ringette Slovakia

- Czech Ringette

- (in Finnish) Turku Ringette History