River Tyburn

The River Tyburn was a stream (bourn) in London, England. Its main successor sewers emulate its main courses, but it resembled the Colne in its county of Middlesex in that it had many distributaries (inland mouths). It ran from South Hampstead, through Marylebone, Mayfair, St James's parish/district and Green Park to meet the tidal Thames at four sites, grouped into pairs. These pairs were near Whitehall Stairs (east of Downing Street), and by Thorney Street, between Millbank Tower and Thames House. Its much smaller cousin, the Tyburn Brook, was a tributary of the Westbourne and the next Thames tributary (west, on the north bank).

Name

A charter of AD 959 appears to mention the river, which it refers to as Merfleot, which probably translates as Boundary Stream, a suggestion reinforced by context, with the river forming the western boundary of the estate described.[1] It is also mentioned in Edgar's Charter, dating from AD 951, where it is rendered as Teo-burna, a name which is thought to mean "two-burn". This may refer to the two branches of the Tyburn which passed through Marylebone and converged to the north of Oxford Street. Ekwall, writing in 1928, suggested that the name meant boundary stream as it followed a course between Lilestone manor and Tyburn manor, but this is now questioned, as both of the river banks were in Tyburn manor.[2]

The Tyburn is also known as the Aye and the Kings Scholars Pond Sewer,[3] though it has to be remembered that the word "sewer" originally referred to an open channel used for the drainage of surface water, and it was illegal to pollute them with offensive material prior to 1815.[4]

Course

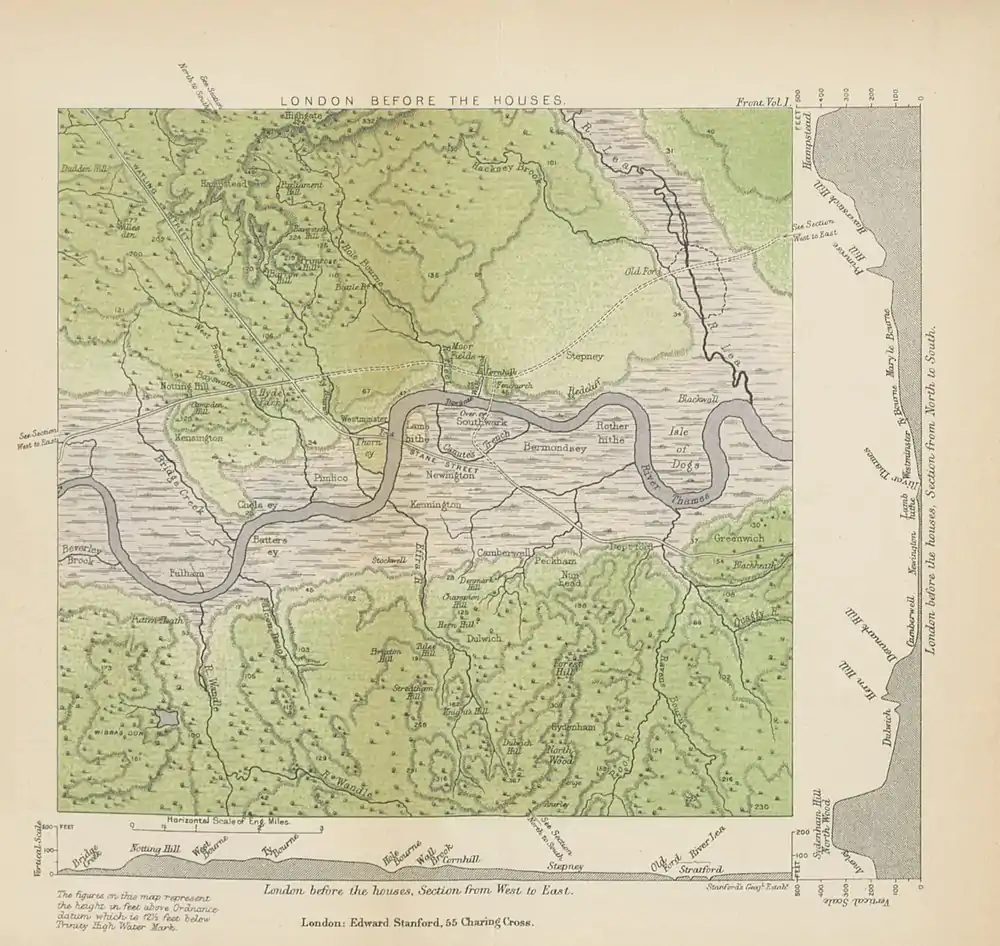

Before it was culverted then used as a sewer this 7-mile (11 km) brook rose from the confluence of two streams in the hills of South Hampstead, deriving from the broad ravine between Barrow and Primrose Hills. Its main source was the Shepherd's Well near Fitzjohn's Avenue, Hampstead.[5] At Green Park the waters split into distributaries, creating Thorney Island on which Westminster Abbey was built.[6] As the map shows, these again split in two, one in the then lower, thus typically Spring tide immersed bank, where Whitehall sits, the other close to Vincent Square, Pimlico, Westminster. The river's current path is fully enclosed by concrete, bricks, parks and roads, flowing through underground conduits for its entire length, including one beneath Buckingham Palace.[6] Several streets, including Marylebone Lane, Jason Street, Gees Court, South Molton Lane then Bruton Lane, defy the grid system of streets as the streets follow the former path of the Tyburn on what was its left bank through Marylebone village.[7] Most of its catchment drains into soakaways in gravel soil, in turn into the chalk water table beneath or into the two-type and hybrid type of drainage set out in Victorian London. In the Tyburn's depression run key (lateral) sewers which connect to Bazalgette's west-to-east Interceptor sewers.[6]

From its source at the Shepherd's Well near Fitzjohns Avenue in Hampstead its successor is Scholar's Pond Sewer southward along that avenue through the Swiss Cottage part of South Hampstead under Avenue Road to Regent's Park. To enter the park's perimeter the part-foul (combined) run is carried enpiped over the Regent's Canal then culverted.[7]

The Tyburn gave its name to the former area of Tyburn, a manor of Marylebone, which was recorded in Domesday Book and which stood approximately at the west end of what is now Oxford Street, where from late medieval times until the 18th century traitors were left following hanging at Tyburn Gallows. Tyburn gave its name to the predecessors of Oxford Street and Park Lane—Tyburn Road and Tyburn Lane respectively.

Grays Antique Centre near the junction of Oxford Street and Davies Street claims that the body of water which can be seen in an open conduit in the basement of its premises is part of the Tyburn;[8][9] it is undoubtedly close to the culverted course of the stream. The Londonist website describes this suggestion as "fanciful", as the modern Tyburn is a sewer.[10]

The stream's southward route followed Lansdowne Row, the north-east of Curzon Street then White Horse Street and the pedestrian avenue of Green Park to the front gates of Buckingham Palace (foot of Constitution Hill) from where one mouth used the depression of St James's Park Lake and Downing Street to reach two close-paired mouths. A third distributary is untraced in the building lines and street layout to Thorney Street close to Lambeth Bridge,[6] whilst a fourth distributary forms the natural collect for a 3-metre (9.8 ft) sewer pipe, King's Scholar's Pond Sewer, to the Victoria Embankment interceptor, saving it from discharging west of Vauxhall Bridge.

Maintenance

The Kings Scholars Pond Sewer was constructed between 1848 and 1856. When the Metropolitan Line was constructed in the early 1860s, it used cut and cover techniques to excavate the tunnels for the underground railway. At Baker Street station, the railway passed beneath the Kings Scholars Pond Sewer, which was supported by a bridge structure attached to the side walls of the tunnel. By the late 2010s, the bridge and sewer had settled below their original level by 6.5 inches (166 mm), and were encroaching on the space needed by the trains. Thames Water, who own the sewer, looked at ways to rectify the problem.[11] Three options were considered. The first involved replacing the bridge and strengthening the walls of the tunnel, but this would have involved closing the railway for three months, at a cost of some £30 million, in addition to the cost of the work. Above the sewer there were reinforced concrete slabs, thought to have been installed during the Second World War, and the second option was to hang a new structure from these. However, further investigation showed that the slabs were not sufficiently robust for this to be safe.[12]

The solution adopted was to construct a Vierendeel truss within the existing sewer, fitted with a glass fibre reinforced plastic (GFRP) liner. The entire structure was made of small modular parts, which could be fitted through a 24-by-30-inch (600 by 750 mm) access hole. When assembled, the structure would be longer than the railway tunnel width, so that its ends were supported by ground beyond the tunnel walls. Once all the components had been manufactured, installation work began in June 2018, and continued until October 2018. The scheme was managed by a joint venture comprising Skanska, Stantec UK and Balfour Beatty, with the McAllister Group carrying out the on-site work. The steel truss is expected to last for 120 years without maintenance, while the GFRP liner has a life span of 50 years.[12] The innovative nature of the solution resulted in the project being given a commendation by the Institution of Structural Engineers in 2021.[13]

References

- Naismith 2019, pp. 131–132.

- Barton & Myers 2016, p. 54.

- Halliday 2008, p. 26.

- Halliday 2008, pp. 28–29.

- Clayton, Antony (2000). Subterranean City: Beneath the Streets of London. London: Historical Publications. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-948667-69-5.

- "Illustrations 1, 4 and the webpage of the Walbrook River page - a synopsis". Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. It cites these books:

The Lost Rivers of London Nicholas Barton (1962)

Subterranean City Anthony Clayton (2000)

London Beneath the Pavement Michael Harrison (1961)

Springs, Streams, and Spas of London Alfred Stanley Foord (1910)

J. G. White, History of The Ward of Walbrook. (1904)

Andrew Duncan, Secret London. (6th Edition, 2009) - Barton, Nicholas (1962). The lost rivers of London: a study of their effects upon London and Londoners, and the effects of London and Londoners upon them. Historical Publications. ISBN 978-0-948667-15-2.

- "Grays: The Lost River Tyburn". 2008. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- "Silent UK – Urban Exploration: River Tyburn". SilentUK.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- "How To Catch A Glimpse Of The Lost River Tyburn". Londonist. 3 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "King's Scholars Pond Sewer Rehabilitation". Stantec. 2019.

- Hanfi & Edwards 2018.

- "King's Scholars Pond Sewer Rehabilitation". Institution of Structural Engineers. 2023. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Barton, Nicholas; Myers, Stephen (2016). The Lost Rivers of London. Historical Publications. ISBN 978-1-905286-51-5.

- Halliday, Stephen (2008). The Great Stink of London. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2580-8.

- Hanfi, Asad; Edwards, Neal (1 October 2018). "King's Scholars' Pond Sewer (2018)". Water Projects Online. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022.

- Naismith, Rory (2019). Citadel of the Saxons, the Rise of Early London. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-13568-0.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Silent UK – Urban Exploration: River Tyburn (2009) at the Wayback Machine (archived 3 June 2013)