Mayfair

Mayfair is an affluent area in the West End of London towards the eastern edge of Hyde Park, in the City of Westminster, between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane. It is one of the most expensive districts in the world.[1]

| Mayfair | |

|---|---|

The Biltmore Mayfair overlooking Grosvenor Square | |

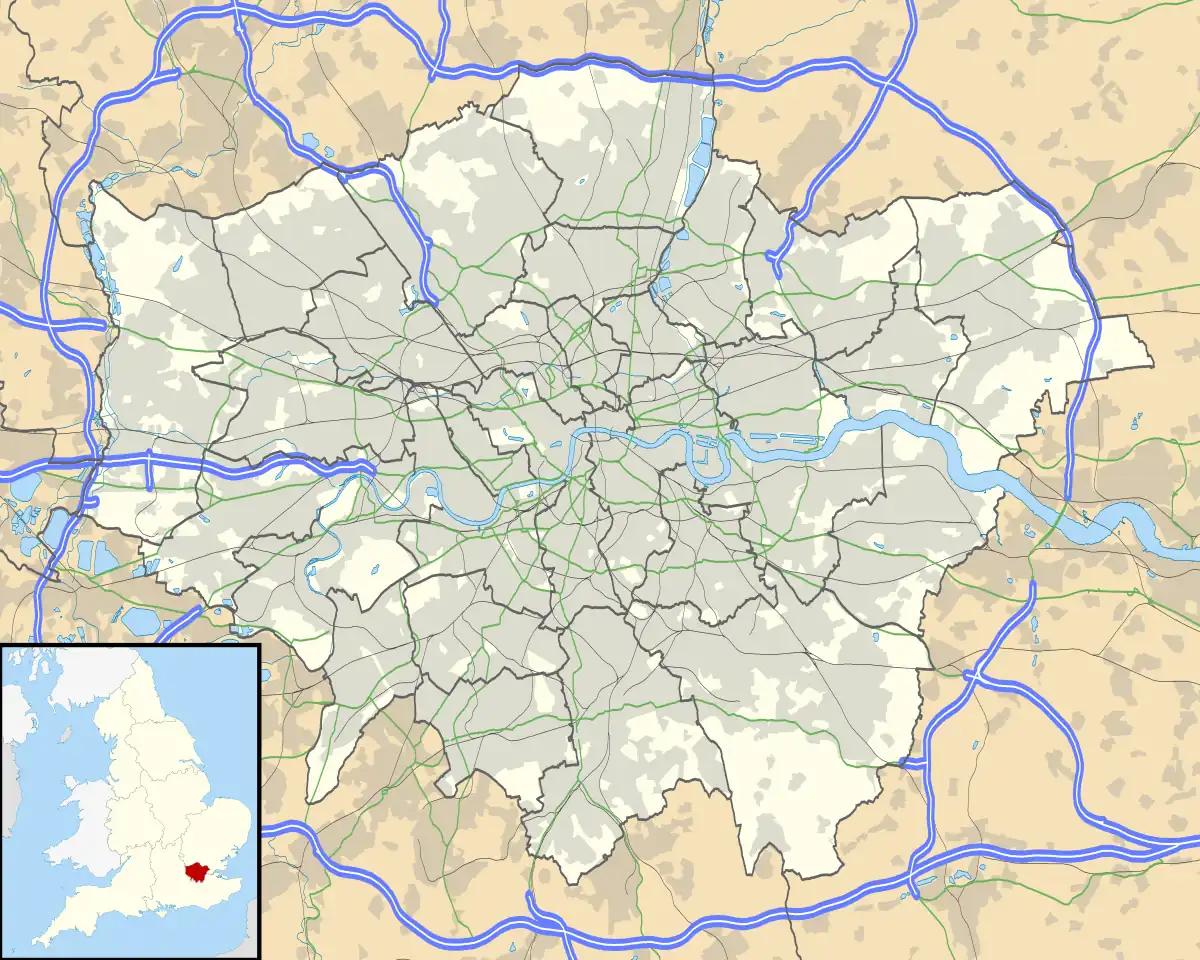

Mayfair  Mayfair Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ285807 |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | London |

| Postcode district | W1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| UK Parliament | |

The area was originally part of the manor of Eia and remained largely rural until the early 18th century. It became well-known for the annual May Fair that took place from 1686 to 1764 in what is now Shepherd Market. Over the years, the fair grew increasingly downmarket and unpleasant, and it became a public nuisance. The Grosvenor family (who became Dukes of Westminster) acquired the land through marriage and began to develop it under the direction of Thomas Barlow. The work included Hanover Square, Berkeley Square and Grosvenor Square, which were surrounded by high-quality houses, and St George's Hanover Square Church.

By the end of the 18th century, most of Mayfair had been rebuilt with high-value housing for the upper class; unlike some nearby areas of London, it has never lost its affluent status. The decline of the British aristocracy in the early 20th century led to the area becoming more commercial, with many houses converted into offices for corporate headquarters and various embassies. Mayfair retains a substantial quantity of high-end residential property, upmarket shops and restaurants, and luxury hotels along Piccadilly and Park Lane. Its prestigious status has been commemorated by being the most expensive property square on the London Monopoly board.

Geography

Mayfair is in the City of Westminster, and mainly consists of the historical Grosvenor estate and the Albemarle, Berkeley, Burlington, and Curzon estates.[2] It is bordered on the west by Park Lane, north by Oxford Street, east by Regent Street, and the south by Piccadilly.[3] Beyond the bounding roads, to the north is Marylebone, to the east Soho, and to the southwest Knightsbridge and Belgravia.[4]

Mayfair is surrounded by parkland; Hyde Park and Green Park run along its boundary.[2] The 8-acre (3.2 ha) Grosvenor Square is roughly in the centre of Mayfair,[5] and its centrepiece, containing numerous expensive and desirable properties.[6]

History

Early history

Following analysis of the alignment of Roman roads, it has been speculated that the Romans settled in the area before establishing Londinium.[7] Whitaker's Almanack suggested that Aulus Plautius built a fort here during the Roman conquest of Britain in AD 43 while waiting for Claudius.[8] The theory was developed in 1993, with a proposal that a town grew outside the fort but was later abandoned as being too far from the River Thames.[9] The proposal has been disputed because of lack of archaeological evidence.[10][11] If there was a fort, it is believed the perimeter would have been where the modern Green Street, North Audley Street, Upper Grosvenor Street and Park Lane now are, and that Park Street would have been the main road through the centre.[8] This area was the manor of Eia in the Domesday Book, and owned by Geoffrey de Mandeville after the Norman Conquest. It was subsequently given to the Abbey of Westminster, who owned it until 1536 when it was taken over by King Henry VIII.[12]

Mayfair consisted mainly of open fields until development began in the Shepherd Market area around 1686–88 to accommodate the May Fair, which had moved from Haymarket in St James's because of overcrowding.[3] There were some buildings before 1686. A cottage in Stanhope Row, dating from 1618, was destroyed in the Blitz in late 1940.[13] A 17th-century English Civil War fortification established in what is now Mount Street was known as Oliver's Mount by the 18th century.[5]

The May Fair

The May Fair was held every year at Great Brookfield (which is now part of Curzon Street and Shepherd Market) from 1 to 14 May.[3] It was established during the reign of Edward I in open fields beyond St. James. The fair was recorded as "Saint James's fayer by Westminster" in 1560. It was postponed in 1603 because of plague, but otherwise continued throughout the 17th century.[14] In 1686, the fair moved to what is now Mayfair.[3] By the 18th century, it had attracted showmen, jugglers and fencers and numerous fairground attractions.[14] Popular attractions included bare-knuckle fighting, semolina-eating contests and women's foot racing.[15]

By the reign of George I, the May Fair had fallen into disrepute and was regarded as a public scandal. The 6th Earl of Coventry, who lived on Piccadilly, considered the fair to be a nuisance and, with local residents, led a public campaign against it. It was abolished in 1764.[3][14] One reason for Mayfair's subsequent boom in property development was that it was able to keep out lower-class activities.[16]

Grosvenor family and estates

Building on Mayfair began in the 1660s on the corner of Piccadilly, and progressed along the north side of that street.[3] Burlington House was started between 1664 and 1665 by John Denham and sold two years later to Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Burlington, who asked Hugh May to complete it. The house was extensively modified through the 18th century, and is the only one of this era to survive into the 21st century.[17]

The origins of major development began when Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet, married Mary Davies, heiress to part of the Manor of Ebury, in 1677.[18] The Grosvenor family gained 500 acres (200 ha) of land, of which around 100 acres (40 ha) lay south of Oxford Street and east of Park Lane.[lower-alpha 1] The land was referred to as "The Hundred Acres" in early deeds.[12]

In 1721, the London Journal reported "the ground upon which the May Fair formerly was held is marked out for a large square, and several fine streets and houses are to be built upon it".[14] Sir Richard Grosvenor, 4th Baronet, asked the surveyor Thomas Barlow to design the street layout, which has survived mostly intact to the present day despite most of the properties being rebuilt.[18][20] Barlow proposed a grid of wide, straight streets, with a large park (now Grosvenor Square) as a centrepiece.[5]

Buildings were constructed in quick succession, and by the mid-18th century the area was covered in houses. Much of the land was owned by seven estates: Burlington, Millfield, Conduit Mead, Albemarle Ground, the Berkeley, the Curzon and, most importantly, the Grosvenor. Of the original properties constructed in Mayfair, only the Grosvenor estate survives intact and owned by the same family,[2] who became the Dukes of Westminster in 1874.[12] Chesterfield Street is one of the few streets that has 18th-century properties on both sides, with a single exception, and is probably the least altered road in the area.[21]

Hanover Square was the first of three great squares to be constructed. It was named after King George I, the Elector of Hanover, soon after his ascension to the throne in 1714. The original houses were inhabited by "persons of distinction" such as retired generals. Although most have been demolished, a small number have survived to the present day. The Hanover Square Rooms became a popular place for classical music concerts, including Johann Christian Bach, Joseph Haydn, Niccolò Paganini and Franz Liszt. A large statue of William Pitt the Younger is sited at the southern end of the square.[22]

In 1725, Mayfair became part of the new parish of St George Hanover Square,[23] which stretched as far east as Bond Street and to Regent Street north of Conduit Street. It ran as far north as Oxford Street and south near to Piccadilly. The parish continued into Hyde Park to the west and extended southwest to St George's Hospital.[24] Most of the area belonged to (and continues to be owned by) the Grosvenor family, though the freehold of some parts belongs to the Crown Estate.[25]

A water supply to the area was built by the Chelsea Water Works, and a royal warrant was issued in 1725 for a reservoir in Hyde Park that could supply water at what is now Grosvenor Gate. In 1835, the reservoir was decorated with an ornamental basin and a fountain in its centre.[23] In 1963, following the widening of Park Lane, it was rebuilt as the Joy of Life Fountain.[26]

Grosvenor Square was planned as the centrepiece of the Mayfair estate. It was laid out around 1725–31 with 51 individual plots for development. It is the second-largest square in London (after Lincoln's Inn Fields) and housed numerous members of the aristocracy until the mid-20th century.[27] By the end of the 19th century, the Grosvenor family were described as "the wealthiest family in Europe" and annual rents for their Mayfair properties reached around £135,000 (now £15,685,000).[19] The square has never declined in popularity and continues to be a prestigious London address into the 21st century. Only two original houses have survived; No. 9, once the home of John Adams, and No. 38 which is now the Indonesian Embassy.[27]

Berkeley House on Piccadilly was named after John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton, who had purchased its land, and that surrounding it, shortly after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. In 1696, the Berkeley family sold the house and grounds to the 1st Duke of Devonshire (who renamed it Devonshire House) on condition that the view from the rear of the house should not be spoiled. Berkeley Square was laid out to the rear of the house in the 1730s; because of the conditions of sale, houses were only built on the east and west sides. The west side still has various mid-18th-century buildings, and the east side now contains offices including Berkeley Square House.[28]

The expansion of Mayfair moved upper-class Londoners away from areas such as Covent Garden and Soho, which were already in decline by the 18th century. Part of its success was its proximity to the Court of St James and the parks, and the well-designed layout. This led to it sustaining its popularity into the 21st century. The requirements of the aristocracy led to stables, coach houses and servants' accommodation being established along the mews running parallel to the streets. Some of the stables have since been converted into garages and offices.[2]

The Rothschild family owned several Mayfair properties in the 19th century. Alfred de Rothschild lived at No. 1 Seamore Place and held numerous "adoration dinners" where the only guest was a female companion. The marriage of his brother Leopold to Marie Perugia took place here in 1881. The house was demolished after the First World War when Curzon Street was extended through the site to meet Park Lane.[29] The future Prime Minister Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, was born in Charles Street in 1847, and grew up in the area.[30]

Mayfair has had a long association with the United States. Pocahontas is believed to have visited in the early 17th century. In 1786, John Adams established the US Embassy on Grosvenor Square. Theodore Roosevelt was married in Hanover Square, and Franklin D. Roosevelt honeymooned in Berkeley Square.[31] A small memorial park in Mount Street Gardens has benches engraved with the names of former American residents in and visitors to Mayfair.[32]

Modern history

The death of Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster in 1899 was a pivotal point in the development of Mayfair, following which all redevelopment schemes not already in operation were cancelled. In the following years, Government budget proposals such as David Lloyd George's establishment of the welfare state in 1909 greatly reduced the power of the Lords. Land value fell around Mayfair, and some leases were not renewed.[33]

Following World War I, the British upper class was in decline, for the reduced workforce meant servants were less readily available and demanded higher salaries. The grandest houses in Mayfair became more expensive to service; consequently, many were converted into foreign embassies. The 2nd Duke of Westminster decided to demolish Grosvenor House and move his residence to Bourdon House. Mayfair attracted commercial development after much of the City of London was destroyed during the Blitz, and many corporate headquarters were established in the area.[2] Several historically important houses were demolished, including Aldford House, Londonderry House and Chesterfield House.[34]

The Canadian High Commission was established at Macdonald House at No. 1 Grosvenor Square in 1961. It is named after the first Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. The Italian Embassy is at No. 4 Grosvenor Square.[35]

The district has become increasingly commercial, with many offices in converted houses and new buildings, though the trend has been reversed in places.[2] The United States embassy announced in 2008 it would move from its long-established location at Grosvenor Square to Nine Elms, Wandsworth, owing to security concerns, despite constructing an £8m security upgrading after the September 11 attacks including 6 ft (1.8 m) high blast walls.[36] Since the 1990s residential properties have become available again, though the rents are among the highest in London.[37] Mayfair remains one of the most expensive places to live in London and the world,[1] and it possesses some exclusive shopping, London's largest concentration of luxury hotels and many restaurants, particularly around Park Lane and Grosvenor Square.[2]

The Al-Thani family, the ruling family of Qatar, and their relatives and associates owned a quarter of the 279 acres of Mayfair by 2006.[38] The north-western part of Mayfair has subsequently been nicknamed "Little Doha".[39][38][40][41] The area has also been called a "Qatari quarter" and 'Qataropolis'.[39] Prominent properties owned in Mayfair by Qataris include Dudley House on Park Lane and Lombard House on Curzon Street.[42][43] Family members also own The Connaught and Claridge's hotels in Mayfair through the Maybourne Hotel Group.[44]

Properties

Churches

St George's, Hanover Square, constructed between 1721 and 1724 by John James, was one of 50 churches built following the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches Act in 1711. Emma, Lady Hamilton, in 1791, poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1814, and Prime Ministers Benjamin Disraeli and H. H. Asquith in 1839 and 1894 respectively were all married in the church. The porch houses two cast-iron dogs rescued from a shop in Conduit Street that was bombed during the Blitz.[45]

Grosvenor Chapel on South Audley Street was built by Benjamin Timbrell in 1730 for the Grosvenor Estate. It was used by American armed forces during the Second World War. The parents of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, are buried in the churchyard.[19]

The Mayfair Chapel on Curzon Street was a popular place for illegal marriages, including over 700 in 1742. James Hamilton, 6th Duke of Hamilton, married Elizabeth Gunning here in 1752. The Marriage Act 1753 stopped the practice of unlicensed marriages. The chapel was demolished in 1899.[46]

Hotels

Having opened in 1837, Brown's Hotel is considered one of London's oldest hotels.[47] Straddling Albemarle and Dover streets, it is thought to have been a popular tea location for Queen Victoria, and it was from the hotel that in 1876 Alexander Graham Bell made the first successful telephone call in Britain. Certain writers were known to stay there frequently; Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book and Agatha Christie's At Bertram's Hotel were each partly written during a visit to Brown's. Theodore Roosevelt enjoyed staying at the hotel and married his fiancée with a reception there in 1886. Now part of Rocco Forte Hotels, the Hotel maintains its popular tea room and has expanded to occupy 11 townhouses.[48]

Claridge's was founded in 1812 as Mivart's Hotel on Brook Street. It was acquired by William Claridge in 1855, who gave it its current name. The hotel was bought by the Savoy Company in 1895 and rebuilt in red brick. It was extended again in 1931. Several European royal families in exile stayed at the hotel during the Second World War. Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia, was born there on 17 July 1945; the Prime Minister Winston Churchill is said to have declared the suite he was born in to be Yugoslav territory.[49]

Flemings Mayfair on Half Moon Street was opened in 1851 by Robert Fleming, who worked for Henry Paget, 2nd Marquess of Anglesey. It is the second-oldest independent hotel in London.[50]

The London Marriott Hotel Grosvenor Square on the corner of Grosvenor Square and Duke Street was the first Marriott Hotel in Britain. It opened as the Europa Hotel in 1961 and was bought by Marriott in 1985. It was a popular place for visitors to the American Embassy.[51]

The Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane is on the former site of Grosvenor House, the home of Robert Grosvenor, 2nd Earl Grosvenor (who later became the 1st Marquess of Westminster). It was built by Arthur Octavius Edwards in the 1920s and has over 450 bedrooms, with 150 luxury flats in the south wing. It was the first London hotel to have a swimming pool.[52]

The Dorchester is named after Joseph Damer, 1st Earl of Dorchester. The first building here was erected by Joseph Damer in 1751, and renamed Dorchester House following the Earl's succession in 1792. The property was purchased by Sir Robert McAlpine and Sons and Gordon Hotels Ltd in 1928 to be converted into a hotel, which opened on 18 April 1931. It was General Dwight Eisenhower's London headquarters in the Second World War. The Duke of Edinburgh held his stag night at the hotel prior to his marriage to Princess Elizabeth.[53]

The May Fair Hotel opened in 1927 on the site of Devonshire House in Stratton Street. It also accommodates the May Fair Theatre, which opened in 1963.[54][55]

The Ritz opened on Piccadilly on 24 May 1906. It was the first steel-framed building to be constructed in London,[56] and it is one of the most prestigious and best-known hotels in the world.[57]

Retail

Mayfair has had a range of exclusive shops, hotels, restaurants and clubs since the 19th century. The district—especially the vicinity of Bond Street—is also the home of numerous commercial art galleries and international auction houses such as Bonhams, Christie's and Sotheby's.[58]

From the early 19th century, tailors, attracted by the affluent and influential residents, began to take up premises on Savile Row in south-eastern Mayfair, beginning in 1803. The earliest extant tailor to move to Savile Row was Henry Poole & Co in 1846. The street's reputation steadily grew throughout the late 19th and early-20th centuries, under the patronage of monarchs, moguls and movie stars, into the global home of men's tailoring; a reputation retained to the present day.[59][60]

Gunter's Tea Shop was established in 1757 at Nos. 7–8 Berkeley Square by the Italian Domenico Negri. Robert Gunter took co-ownership of the shop in 1777, and full ownership in 1799. During the 19th century it became a fashionable place to buy cakes and ice cream, and was well-known for its range of multi-tiered wedding cakes. The shop moved to Curzon Street in 1936 when the eastern side of Berkeley Square was demolished, until closing in 1956. The business as a whole survived until the late 1970s.[61]

Mount Street has been a popular shopping street since Mayfair was developed in the 18th century. It was largely rebuilt between 1880 and 1900 under the direction of the 1st Duke of Westminster, when the nearby workhouse was relocated to Pimlico. It now houses a number of shops dealing with luxury trades.[62]

Shepherd Market has been called the "village centre" of Mayfair. The current buildings date from around 1860, and house food and antique shops, pubs and restaurants. The market had a reputation for high-class prostitution. In the 1980s, Jeffrey Archer was alleged to frequent the area and was accused of visiting Monica Coghlan, a call girl in Shepherd Market, which eventually led to a libel trial and his imprisonment for perverting the course of justice.[63]

Alongside Burlington House is one of London's most luxurious shopping areas, the Burlington Arcade. It was designed by Samuel Ware for George Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington, in 1819. The arcade was designed with tall walls on either side to prevent passers-by throwing litter into the Earl's garden. Ownership of the arcade passed to the Chesham family. In 1911, another storey was added by Beresford Pite, who also added the Chesham arms. The family sold the arcade to the Prudential Assurance Company for £333,000 (now £20,562,000) in 1926. It was bombed during the Second World War and subsequently restored.[64]

Allens of Mayfair, one of the best-known butchers in London, was founded in a shop on Mount Street in 1830. It held a Royal warrant of appointment to supply meat to the Queen, as well as supplying several high-profile restaurants. After accruing spiralling debts, it was sold to Rare Butchers of Distinction in 2006.[65] The Mayfair premises closed in 2015, but the company retains an online presence.[66]

Scott's restaurant moved from Coventry Street to Nos. 20–22 Mount Street in 1967.[67] In 1975, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombed the restaurant twice, killing one and injuring 15 people.[68]

South Audley Street is a major shopping street in Mayfair running from north to south from Grosvenor Square to Curzon Street.[69] Originally a residential street, it was redeveloped between 1875 and 1900. Retailers include china and silverware specialists Thomas Goode and gunsmiths James Purdey & Sons.[70][71]

Museums and galleries

Numerous galleries have given Mayfair a reputation as an international art hub.[72] The Royal Academy of Arts, based in Burlington House, was founded in 1768 by George III and is the oldest fine arts society in the world. Its founding president was Sir Joshua Reynolds. The academy holds classes and exhibitions, and students have included John Constable and J. M. W. Turner. It moved from Somerset House to Trafalgar Square in 1837, sharing with the National Gallery, before moving to Burlington House in 1868. The academy hosts an annual Summer Exhibition, showing over 1,000 contemporary works of art that can be submitted by anyone.[73]

The Fine Art Society gallery was established at No. 148 New Bond Street in 1876.[74] Other galleries in Mayfair include the Maddox Gallery on Maddox Street,[75] and the Halcyon Gallery.[76]

The Handel House Museum at No. 25 Brook Street opened in 2001. George Frideric Handel was the first resident from 1723 until his death in 1759. Most of his major works, including Messiah, and Music for the Royal Fireworks were composed here. The museum held an exhibition of Jimi Hendrix, who lived in an upper-floor flat in neighbouring No. 23 Brook Street in 1968–69.[77][78]

The Faraday Museum in Albemarle Street occupies a basement laboratory used by Michael Faraday for his experiments with electromagnetic rotation and motors at the Royal Institution. It opened in 1973 and exhibits include the first electric generator designed by Faraday, along with various notes and medals.[79]

Business

Cadbury's head office was formerly at No. 25 Berkeley Square in Mayfair. In 2007, Cadbury Schweppes announced that it was moving to Uxbridge in order to cut costs.[80]

Other

Bourdon House, one of the oldest properties in Mayfair, was constructed by Thomas Barlow between 1723 and 1725 as part of the original development. An additional storey was added around 1864–65. In 1909, the 2nd Duke of Westminster ordered major refurbishments and the expansion of a three-storey wing. He moved out of Grosvenor House in 1916 into this, where he stayed until his death in 1953.[81]

Crewe House was built in the late 18th century on the site of a house on Curzon Street owned by Edward Shepherd, a key builder and architect around Mayfair. It was bought by James Stuart-Wortley, 1st Baron Wharncliffe in 1818 and became known as Wharncliffe House. In 1899, it was purchased by Robert Crewe-Milnes, Earl Crewe, giving it its current name. The house is part of the Saudi Arabian Embassy.[46]

Mayfair has many blue plaques on buildings for its prominent residents. Standing at the corner of Chesterfield Street and Charles Street, one can see plaques for William, Duke of Clarence and St Andrews (later King William IV), Prime Minister Lord Rosebery, the writer Somerset Maugham and Regency-era fashion icon Beau Brummell.[82]

Transport

While there are no London Underground stations inside Mayfair, there are several on the boundaries. The Central Line stops at Marble Arch, Bond Street and Oxford Circus along Oxford Street along the northern edge, and Piccadilly Circus and Green Park are along the Piccadilly line on the southern side, along with Hyde Park Corner close by in Knightsbridge.[83]

Down Street tube station opened in 1907 as "Down Street (Mayfair)".[84] It closed in 1932[85] but was used during the Second World War by the Emergency Railway Committee, and briefly by Churchill and the war cabinet while waiting for the War Rooms to be ready.[86] While there is only one bus route in Mayfair itself, the 24-hour route C2,[87] there are many bus routes along the perimeter roads.[88]

Cultural references

Mayfair (spelled "May Fair") is the home of Sir Brian in Thackeray's The Newcomes, and otherwise features as the most desirable part of London.[89]

Mayfair has featured in a number of novels, including Evelyn Waugh's A Handful of Dust (1934) and P. G. Wodehouse's The Mating Season (1949). It is a partial setting for Jane Austen's Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Michael Arlen's The Green Hat (1924).[90] Oscar Wilde lived in Grosvenor Square between 1883 and 1884, and referred to it in his works.[91] He regularly socialised in the artistic quarter along Half Moon Street, which is mentioned in both The Importance of Being Earnest and The Picture of Dorian Gray.[92]

Mayfair is the most expensive property on the standard British Monopoly board at £400, and is part of the dark blue set with Park Lane. It commands the highest rents of all properties; landing on Mayfair with a hotel costs £2,000.[93] The price is a reference to the property values in the area, which have remained consistently high, with real-life rent as much as £36,000 per week.[37] At the time the board was being designed in the 1930s, Mayfair still had a significant upper-class residential population.[82]

The department store Debenhams became one of the first companies in Britain to have a dedicated business telephone number, Mayfair 1, in 1903.[94]

See also

References

Citations

- Cox, Hugo (11 November 2016). "Mayfair: London's most expensive 'village'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 536.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 535.

- "Mayfair". Google Maps. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- F H W Sheppard, ed. (1977). The Development of the Estate 1720–1785: Layout. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "From swamps to shopping centres: How the Grosvenor family came to own some of the UK's most desirable property". The Daily Telegraph. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 494.

- "Roman Mayfair". Whitaker's Almanack. Joseph Whitaker. 1994. p. 1118.

- Sole, Bill (1992). "Metropolis in Mayfair?". The London Archaeologist. 7 (5): 122–126.

- Clark, John; Sheldon, Harvey (30 November 2008). Londinium and Beyond: Essays on Roman London. David Brown Book Company. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-902771-72-4.

- Fuentes, Nicholas (1992). "The Plautian invasion base". The London Archaeologist. 7: 238.

- F H W Sheppard, ed. (1977). The Acquisition of the Estate. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "City of Westminster green plaques". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- Walford, Edward (1878). Mayfair. pp. 345–359. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Moore 2003, pp. 284–85.

- Moore 2003, p. 285.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 116.

- Great Estates 2006, p. 14.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 358.

- Residence, Hyde Park (12 July 2022). "mayfair, london (an insider's guide)". Hyde Park Residence. Cultureshock. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 161.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 381–382.

- F H W Sheppard, ed. (1977). "The Development of the Estate 1720–1785: Other Features of the Development". Survey of London. London. 39, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 1 (General History): 29–30. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- St Georges parish, Hanover Square. With the views of the church and chapels of ease from the original survey of the late Mr Morris (Map). British Library. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Great Estates 2006, p. 6.

- "Joy of Life Fountain". Royal Parks. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 359.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 59.

- "1, Seamore Place, London, England". Rothschild Archive. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- James, Robert Rhodes (1963). Rosebery. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-857-99219-9.

- Moore 2003, p. 288.

- Moore 2003, p. 289.

- F H W Sheppard, ed. (1977). The Estate in the Twentieth Century. pp. 67–82. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Middleton, Christopher (20 May 2014). "How did Mayfair become London's most desirable area?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 360.

- "US embassy to move from Grosvenor Square to industrial estate". The Daily Telegraph. 2 October 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- "A Potted History of Mayfair". Manors. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Rodionova, Zlata (31 March 2006). "London property crisis: Qatari investors now own £1bn in Mayfair real estate". The Independent. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Prynn, Jonathan (2 September 2015). "World's most expensive mews house: former garage in Mayfair sold to Qatari for £24m". Evening Standard. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Townsend, Sarah (16 September 2016). "Foreign investors seek new London property sites". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Davies, Rob; Smith, Joseph (5 November 2022). "How Qatar bought up Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "Sheikh Shack". Vanity Fair. February 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Leppard, David (6 October 2002). "Designer 'paid Pounds 2m bribe' for contract". The Times. p. 9. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- "The billion-pound battle over Claridge's hotel from Belfast to Qatar". The Guardian. 10 October 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 759.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 228.

- Trilivas, Nicole. "Inside London's Oldest Hotel". Forbes.

- "The History of the Brown's Hotel in London – Rocco Forte". www.roccofortehotels.com.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 192.

- "Step Inside London's Second-Oldest Hotel Flemings Mayfair". Forbes. 9 June 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "London Marriott Hotel Grosvenor Square". Marriott International. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 358–9.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 244.

- "The May Fair Theatre private screening room". www.themayfairhotel.co.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 536, 679.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 695.

- "London Campus signs collaborative agreement with The Ritz London". Coventry University. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 537.

- "Savile Row tailors: the GQ Guide". British GQ. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- "Henry Poole Savile Row – The History at London's Savile Row". Henry Poole Savile Row. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 365.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 563.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 834.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 115.

- "But Allen of Mayfair is sold to rival from Lewisham, says Supplier to Queen's kitchen collapses". The Daily Telegraph. 29 May 2006. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Mount Street laments the loss of Allens, Mayfair's legendary butchers shop". West End Extra. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 828.

- Melaugh, Dr Martin. "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1975". cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- South Audley Street: Introduction. pp. 290–291. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 851.

- "Mayfair Sth Audley Street, London Sth Audley Street W1 Mayfair". Mayfair-london.co.uk. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- "Meet Mayfair's Bright Young Art Gallerists & Dealers". Luxury London. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 705.

- "Art Sales: can The Fine Art Society survive in Mayfair?". The Daily Telegraph. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Maddox Gallery". visitlondon.com. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Khan, Tabish (13 October 2016). "Take Our Tour Of Some Of London's Best Art Exhibitions". Londonist. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 380.

- Kennedy, Maev (16 May 2010). "Jimi Hendrix and Handel: Housemates separated by time". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 286.

- Muspratt, Caroline (1 June 2007). "Cadbury swaps Mayfair for Uxbridge". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 84.

- Moore 2003, p. 287.

- "Tube Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Moore 2003, pp. 285–6.

- James Leasor (2001). War at the Top. House of Stratus. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-755-10049-1.

- Richard Holmes (2011). Churchill's Bunker. Profile Books. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-847-65198-3.

- "Route C2". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- "Central London Bus Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- R.D. McMaster (18 June 1991). Thackeray's Cultural Frame of Reference: Allusion in The Newcomes. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-1-349-12025-3.

- Glinert 2007, p. 325.

- Wilde, Oscar; Bristow, Joseph (1 January 2005). The complete works of Oscar Wilde 3. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 419. ISBN 0-198-18772-6.

- "Live like the literati: homes owned by famous writers". The Daily Telegraph. 18 September 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Moore 2003, p. 283.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 233.

Sources

- Glinert, Ed (2007). Literary London: A Street by Street Exploration of the Capital's Literary Heritage. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-90159-6.

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-43386-6.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

- The Great Estates – Who owns London? (Report). New London Architecture. 2006.

Further reading

- "Mayfair". London. Let's Go. 1998. p. 151+. ISBN 9780312157524. OL 24256167M.

- Borer, Mary Cathcart (1975). The Years of Grandeur: The Story of Mayfair. London: W. H. Allen.

- Bradbury, Oliver (2008). The Lost Mansions of Mayfair. Historical Publications. ISBN 978-1-905-28623-2.

- Perry, Maria (1999). Mayfair Madams. London: André Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-99476-9.