River cooter

The river cooter (Pseudemys concinna) is a species of freshwater turtle in the family Emydidae. The species is native to the central and eastern United States, but has been introduced into parts of California, Washington, and British Columbia.[3]

| River cooter | |

|---|---|

| |

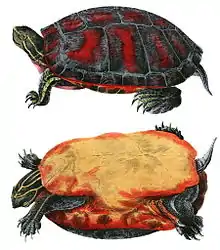

| Eastern river cooter, P. concinna concinna | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Pseudemys |

| Species: | P. concinna |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudemys concinna (Le Conte, 1830) | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Geographic range

P. concinna is found from Virginia south to central Georgia, west to eastern Texas, Oklahoma, and north to southern Indiana.[4]

Habitat

P. concinna is usually found in rivers with moderate current, as well as lakes and tidal marshes.[4]

Subspecies

There are two subspecies which are recognized as being valid.[5]

- Pseudemys concinna concinna (LeConte, 1830) – eastern river cooter

- Pseudemys concinna suwanniensis Carr, 1937 – Suwannee cooter – sometimes regarded as a separate species, P. suwanniensis

Nota bene: A trinomial authority in parentheses indicates that the subspecies was originally described in a genus other than Pseudemys.

The coastal plain cooter or Florida cooter (P. floridana) was formerly considered a subspecies of P. concinna, but is now considered a distinct species.[6][7]

Name

The genus Pseudemys includes several species of cooters and red-bellied turtles. Pseudemys concinna is the species known as the river cooter. The name "cooter" may have come from an African word "kuta" which means "turtle" in the Bambara and Malinké languages, brought to America by African slaves.[8]

Behavior

The river cooter basks on logs or sun-warmed rocks, and is frequently found in the company of other aquatic basking turtles (sliders and painteds) sometimes piled up on top of each other. All are quick to slip into the water if disturbed. Diurnal by nature, P. concinna wakes with the warming sun to bask and forage. It can move with surprising speed in the water and on land. It is not unusual for it to wander from one body of fresh water to another, but many individuals seem to develop fairly large home ranges, which they seldom or never leave. It sleeps in the water, hidden under vegetation. In areas that are quite warm it remains active all winter, but in cooler climates can become dormant during the winter for up to two months, in the mud, underwater. It doesn't breathe during this time of low metabolism, but can utilize oxygen from the water, which it takes in through the cloaca. The river cooter prefers to be well hidden under aquatic plants during the winter dormancy period or while sleeping each night.[9]

Diet

The species P. concinna is highly omnivorous and will eat anything, plant or animal, dead or alive. Diet seems to be determined by available food items. While some writers feel that this species of turtle will not eat meat, predatory behavior has been observed. Although it can't swallow out of water, it will leave the water to retrieve a tasty bug or worm, returning to the water to swallow. It will also enthusiastically chase, kill and eat small fish. It has also been observed eating carrion found along the river's edge. The river cooter has tooth-like cusps in the upper jaw, probably an adaptation to aid in eating leaves and fibrous vegetation. Its primary diet includes a wide variety of aquatic plants, and some terrestrial plants that grow near the water's edge. It will happily take fallen fruits as well. In captivity, any kind of plant will be eaten, and some "meats", too. Turtles will also take calcium in a separate form, such as a cuttlebone, so that the turtle can self-regulate calcium intake.[9]

Conservation status

The river cooter is faced with loss of habitat, predation by animals, slaughter on the highways, and use as a food source by some people. Hatchlings are particularly vulnerable. During their overland scramble to the river, many hatchlings will be taken by avian and mammal predators. Alligators and muskrats await them in the water. Some will be taken and sold to pet stores. Populations are down in some areas, and there have been increasing reports of injured turtles, but this species as a whole is hardy, and continues to thrive. P. concinna can live 40 years or more.[9]

Reproduction

The mating habits of the river cooter are very similar to those of the red-eared slider. As with the other basking turtles, the males tend to be smaller than females. The male uses his long claws to flutter at the face of the much larger female. Often, the female ignores him. After detecting what may be a pheromone signal while sniffing at a female's tail, a male river cooter will court a female by swimming above her, vibrating his long nails and stroking her face. Females have also been observed doing this to initiate courtship. If the female is receptive, she will sink to the bottom of the river and allow the male to mount for mating.[9] If she does mate, after several weeks the female crawls upon land to seek a nesting site. Females often cross highways looking for suitable nesting spots. Females will lay between 12 and 20 eggs at a time, close to water. The eggs hatch within 45 to 56 days and the hatchlings will usually stay with the nest through their first winter.

Mating takes place in early spring. Nesting usually occurs from May to June. The female chooses a site with sandy or loamy soil, within 100 ft (30 m) of the river's edge. She looks for a rather open area, with no major obstacles for the future hatchings to negotiate on their way to the river. The nest is dug with the hind feet. She lays 10–25 or more eggs in one or more clutches. Eggs are ellipsoidal, approximately 1.5 inches (4 cm) long. Incubation time is determined by temperature, but averages 90–100 days. Hatchlings generally emerge in August or September. There have been reported instances of late clutches over-wintering and hatching in the spring. A hatchling will have a round carapace, about 1.5 inches (4 cm) diameter, that is green with bright yellow markings.[9]

In the wild

In the wild P. concinna feeds on aquatic plants, grasses, and algae. Younger ones tend to seek a more protein enriched diet such as aquatic invertebrates, crustaceans, and fish. Older turtles may occasionally seek prey as well, but mostly partake of a herbivorous diet.

The river cooter can sometimes be found basking in the sun, but is very wary and will quickly retreat into the water if approached. Otherwise, it is difficult to find in the water, which may be due to its ability to breathe while fully submerged. As a result, little is known about its biology and behavior.

The river cooter lives in a wide variety of freshwater and even brackish locations. Rivers, lakes, ponds and marshes with heavy vegetation provide ideal habitat. Large webbed feet make the river cooter an excellent swimmer, capable of negotiating moderately strong river currents of major river systems. It will collect in large numbers on peninsular floodplains associated with a river oxbow.[9]

Conservation

In Indiana, the river cooter is listed as an endangered species.[10]

United States federal regulations on commercial distribution

A 1975 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation bans the sale (for general commercial and public use) of turtle eggs and turtles with a carapace length of less than 4 inches (100 mm). This regulation comes under the Public Health Service Act and is enforced by the FDA in cooperation with State and local health jurisdictions. The ban has been effective in the U.S. since 1975 because of the public health impact of turtle-associated Salmonella. Turtles and turtle eggs found to be offered for sale in violation of this provision are subject to destruction in accordance with FDA procedures. A fine of up to $1,000 and/or imprisonment for up to one year is the penalty for those who refuse to comply with a valid final demand for destruction of such turtles or their eggs.[11]

Many stores and flea markets still sell small turtles due to an exception in the FDA regulation which allows turtles under 4 inches (100 mm) to be sold "for bona fide scientific, educational, or exhibitional purposes, other than use as pets."[12]

As with many other animals and inanimate objects, the risk of Salmonella exposure can be reduced by following basic rules of cleanliness. Small children must be taught not to put the turtle in their mouth and to wash their hands immediately after they finish "playing" with the turtle, feeding it, or changing the water.

References

- van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2011 assessment]. "Pseudemys concinna". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T163444A97425355. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T163444A5606651.en. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 192–194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- "River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna)". iNaturalist. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- "River Cooter". eNature. Archived from the original on 2009-09-05. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- Species Pseudemys concinna at The Reptile Database . www.reptile-database.org.

- Rhodin, Anders G.J. (2021-11-15). Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (9th Ed.). Chelonian Research Monographs. Vol. 8. Chelonian Research Foundation and Turtle Conservancy. doi:10.3854/crm.8.checklist.atlas.v9.2021. ISBN 978-0-9910368-3-7. S2CID 244279960.

- "Pseudemys floridana". The Reptile Database. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- "Cooters". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- "RIVER COOTER". Turtle Puddle. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- Indiana Legislative Services Agency (2011), "312 IAC 9-5-4: Endangered species of reptiles and amphibians", Indiana Administrative Code, retrieved 28 Apr 2012

- GCTTS FAQ: "4 Inch Law", actually an FDA regulation

- Turtles intrastate and interstate requirements; FDA Regulation, Sec. 1240.62, page 678 part d1.

Further reading

- Behler, John L.; King, F. Wayne (1979). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 743 pp., 657 plates. (Chrysemys concinna, pp. 447-448 + Plate 287).

- Conant R (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. xviii + 429 pp. + Plates 1-48. ISBN 0-395-19979-4 (hardcover), ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Chrysemys concinna, pp. 63-65 + Plates 6, 10 + Map 23).

- LeConte J (1830). "Description of the Species of North American Tortoises". Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York 3: 91-131. (Testudo concinna, new species, pp. 106-108). (in English and Latin).

- Powell R, Conant R, Collins JT (2016). Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Fourth Edition. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. xiv + 494 pp. 47 plates, 207 figures. ISBN 978-0-544-12997-9. (Pseudemys concinna, pp. 212-213 + Plates 17, 22; P. suwanniensis, p. 216 + Plate 18 + Figure 83 on p. 180 + photo on p. 172).

- Seidel, Michael E. (1994). "Morphometric analysis and taxonomy of cooter and red-bellied turtles in the North American genus Pseudemys (Emydidae)". Chelonian Conservation and Biology 1 (2): 117-130.

- Smith, Hobart M.; Brodie, Edmund D. Jr (1982). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. New York: Golden Press. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3 (paperback), ISBN 0-307-47009-1 (hardcover). (Pseudemys concinna, pp. 58-59).

- Stejneger L, Barbour T (1917). A Check List of North American Amphibians and Reptiles. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 125 pp. (Pseudemys concinna, p. 119).