Müller-Thurgau

Müller-Thurgau (German pronunciation: [ˌmʏlɐ ˈtuːɐ̯ɡaʊ]) is a white grape variety (sp. Vitis vinifera) which was created by Hermann Müller from the Swiss Canton of Thurgau in 1882 at the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute in Germany. It is a crossing of Riesling with Madeleine Royale. It is used to make white wine in Germany, Austria, Northern Italy, Hungary, England, Australia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Belgium and Japan. There are around 22,201 hectares (54,860 acres)) cultivated worldwide,[1] which makes Müller-Thurgau the most widely planted of the so-called "new breeds" of grape varieties created since the late 19th century. Although plantings have decreased significantly since the 1980s, as of 2019 it was still Germany's second most planted variety at 11,400 hectares and 11.4% of the total vineyard surface.[1] In 2007, the 125th anniversary was celebrated at the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute. Müller-Thurgau is also known as Rivaner (Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, and especially for dry wines), Riesling x Sylvaner, Riesling-Sylvaner, Rizvanec (Slovenia) and Rizlingszilváni (Hungary).

| Müller-Thurgau | |

|---|---|

| Grape (Vitis) | |

Müller-Thurgau grapes | |

| Color of berry skin | Blanc |

| Species | Vitis vinifera |

| Also called | Rivaner, Riesling x Sylvaner, Rizvanec |

| Origin | Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute, Germany |

| Notable regions | Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Slovakia |

| Hazards | Mildew |

| VIVC number | 8141 |

History of the grape variety

Most grapes have been created from a desire to harness qualities in two separate grapes and to generate a new vine that combines the qualities of both.

When Dr. Müller created the grape in the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute in the late 19th century, his intention was to combine the intensity and complexity of the Riesling grape with the ability to ripen earlier in the season that the Silvaner grape possesses. Although the resulting grape did not entirely attain these two qualities, it nonetheless became widely planted across many of the German wine-producing regions.

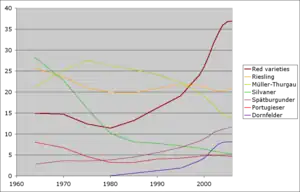

By the 1970s, Müller-Thurgau had become Germany's most-planted grape. A possible reason for the popularity of this varietal is that it is capable of being grown in a relatively wide range of climates and soil types. Many of these vines were planted on flat areas that were not particularly suitable for growing other wine grapes because it was more profitable than sugar beet, which was the main alternative crop in those locations. The vines mature early and bring large yield quantities, and are less demanding as to planting site than for example Riesling. Müller-Thurgau wines are mild due to low acidic content, but nevertheless fruity. The wines may be drunk while relatively young, and with few exceptions are not considered to improve with age. These facts meant that Müller-Thurgau provided an economical way to cheaply produce large amounts of medium sweet German wines, such as Liebfraumilch and Piesporter, which were quite popular up until the 1980s.

The turning point in Müller-Thurgau's growth however was the winter of 1979, when on 1 January there was a sharp fall in temperatures, to 20 °F (−7 °C) in many areas, which devastated most of the new varieties, but did not affect the varieties such as Riesling which have much more hardy stems, after hundreds of years of selection. In the decades since then, the winemakers have begun to grow a wider variety of vines, and Müller-Thurgau is now less widely planted in Germany than Riesling, although still significant in that country and worldwide.

While the total German plantations of Müller-Thurgau are declining, the variety is still in third place among new plantations in Germany, after Riesling and Pinot noir, with around 8% of all new plantations in the years 2006-2008.[5]

Genealogy

Recent DNA fingerprinting has in fact determined that the grape was created by crossing Riesling with Madeleine Royale,[6] not Silvaner or any other suggested grape variety. But there has been some confusion on the way. In 1996, Chasselas seemed to be a valid candidate, and in 1997 the Chasselas variety Admirable de Courtiller was specified. However, this was shown to be wrong when the reference grape that was believed to be Admirable de Courtiller was proven in the year 2000 to be Madeleine Royale.[7] Madeleine Royale was long believed to be a Chasselas seedling, but modern DNA fingerprinting methods suggest that it is actually a crossing of Pinot and Trollinger.

German growing regions

As of 2019, German regional plantings stood at:[1]

- Rheinhessen, 4,084 ha 4,084 hectares (10,090 acres)

- Baden, 2,357 hectares (5,820 acres)

- Palatinate, 1,808 hectares (4,470 acres)

- Franconia, 1,493 hectares (3,690 acres)

- Mosel, 889 hectares (2,200 acres)

- Nahe, 507 hectares (1,250 acres)

- Saale-Unstrut, 121 hectares (300 acres)

Outside of Germany, the grape has achieved a moderate degree of success in producing lively wines in Italy, southern England (where most other grapes will not ripen in many years) Luxembourg (where it is called Rivaner), Czech Republic, and the United States.

In Germany, it has long been common to blend Müller-Thurgau with Bacchus, or small amounts of Morio Muscat to enhance its flavours.[8][9] Both are highly aromatic which don't work very well in varietal wines on their own because of a lack of acidity or structure.

Growing regions

Europe

- Hungary, 8,000 ha (20,000 acres)

- Belgium, 0.5 ha at Château Bon Baron in Lustin.

It is authorised for all still wine AOCs : Côtes de Sambre et Meuse,[10] Hageland,[11] Haspengouw,[12] et Heuvelland.[13] - Austria, 5236 ha (12,933 acres) (7,8%)

- Czech Republic

- Slovakia 1.362 ha

- Luxembourg, as Rivaner

- Switzerland, as Riesling x Silvaner,

- Italy

- United Kingdom

- Republic of Macedonia, endemic species as Kratosija

- Slovenia

- Croatia, locally known as Rizvanac

- France

- Moldavia

- Netherlands

- Germany

Rest of the world

- Australia – Mudgee wine region

- New Zealand – Now a marginal grape.

- United States of America

- Japan

- China

Synonyms

Synonyms for Müller-Thurgau include Miler Turgau, Müller, Müller-Thurgaurebe, Müllerka, Müllerovo, Muller-Thurgeau, Mullerka, Mullerovo, Riesling-Silvaner, Riesling-Sylvamer, Riesling x Silavaner, Rivaner, Rizanec, Rizlingsilvani, Rizlingszilvani, Rizlingzilvani, Rizvanac, Rizvanac Bijeli, Rizvanec, Rizvaner.[6]

References

- German Wine Institute (2021), German Wine Statistics 2020/2021 (PDF) (in German and English), Mainz

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), Format: PDF, KBytes: 219 - German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2004-2005 Archived 2009-09-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2005-2006 Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2006-2007 Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Deutsches Weininstitut: Basisdaten 2009 Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on November 18, 2009.

- Vitis International Variety Catalogue: Müller-Thurgau Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on May 26, 2008.

- Dr Erika Dettweiler et al.: "Grapevine cultivar Müller-Thurgau and its true to type descent", Vitis 39(2), pp. 63–65, 2000.

- Jancis Robinson, ed. (2006). "Müller-Thurgau". Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 461–462. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Jancis Robinson, ed. (2006). "Bacchus". Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 58. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Decree text of Côtes de Sambre et Meuse (in French).

- Decree text of Hageland (in Dutch).

- Decree text of Haspengouw (in Dutch).

- Decree text of Heuvelland (in Dutch).

Further reading

- Oz Clarke & Margaret Rand: Clarkes großes Lexikon der Rebsorten, München 2001.

- Helmut Becker: 100 Jahre Rebsorte Müller-Thurgau, Der Deutsche Weinbau 12/1982.

External links

- Geisenheim University – The Professor Müller-Thurgau-Award.