Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island (/ˈroʊənoʊk/) is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of English colonization.

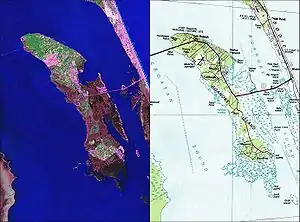

Maps of Roanoke Island taken from the U.S Geological Survey and the U.S Department of the Interior and NASA. | |

Roanoke Island Location of Roanoke Island  Roanoke Island Roanoke Island (North America) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 35.889°N 75.661°W |

| Area | 17.95 sq mi (46.5 km2) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | North Carolina |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 6,724 (2000) |

About 8 mi (13 km) long and 2 mi (3.2 km) wide, the island lies between the mainland and the barrier islands near Nags Head. Albemarle Sound lies on its north, Roanoke Sound on the eastern, Croatan Sound on the west, and Wanchese CDP lies at the southern end. The town of Manteo is located on the northern portion of the island, and is the county seat of Dare County. Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is on the north end of the island. The island has a land area of 17.95 square miles (46.5 km2) and a population of 6,724 as of the 2000 census.

Today U.S. Highway 64, a major highway, connects mainland North Carolina to the Outer Banks, as well as Roanoke Island. The island has recreational and water features, plus historical sites and an outdoor theater that form one of the major tourist attractions of Dare County.

The residents of Roanoke Island are governed by the Dare County Board of Commissioners. They are located within North Carolina's 1st congressional district.

Etymology

The island was named by English colonists after the Roanoke indigenous people who resided here for generations, at least 800 years prior to the arrival of the English in the New World. The meaning of the word Roanoke is derived from the Powhatan language, which was geographically close to the Roanoke. Roanoke means "white beads made from shells" (or more literally "things rubbed smooth by hand"). White beads were used as ornaments and currency among the Coastal Algonquian peoples of Virginia and North Carolina.

John Smith, an English explorer and one of the first governors of Jamestown, Virginia, recorded the usage of the word Rawrenock in the Algonquin Powhowaten language.

Cuscarawaoke, where is made so much Rawranoke or white beads that occasion as much dissention among the savages, as gold and silver amongst Christians ....[1]

In the context of the quote, Rawranoke refers to the items being traded, not the people. The Roanoke people became known by the English for trading shells prevalent at Roanoke Island and the other barrier islands of the Outer Banks. The Roanoke likely also exported the shells and white beads made from them to other distant cultures across the continent.

History

Overview

For millennia, this island was a site of ancient indigenous settlements. Archeological excavations in 1983 at the Tillett Site at Wanchese have revealed evidence of various cultures dating back to 8000 BC. Wanchese was used as a seasonal fishing village for 1500 years before English colonial settlement. Ancestors of the Algonquian-speaking Roanoke are believed to have coalesced as a people in about 400 CE, based on archeology and linguistics.[2]

Roanoke Island was the site of the Roanoke Colony, an English settlement initially established in 1585 by Sir Walter Raleigh. A group of about 120 men, women and children arrived in 1587. Shortly after arriving here, colonist Eleanor Dare, daughter of Governor John White, gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in North America. Governor White returned to England later that year for supplies.

Due to impending war with Spain, White was unable to return to Roanoke Island until 1590. When he arrived, the colony had vanished. The fate of those first colonists remains a mystery to this day. Much speculation formed about their fate.[3] Archaeologists, historians, and other researchers continue to work to resolve the mystery. Visitors to the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site can watch The Lost Colony, the second-longest-running outdoor theatre production in the United States, which presents a conjecture about the decline of Roanoke Colony.

Roanoke Island is one of the three oldest surviving English place-names in the U.S. Along with the Chowan and Neuse rivers, it was named in 1584 by Captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, sent by Sir Walter Raleigh.[4]

Another colony, more populous than the 16th century settlement by Raleigh, was developed at the island during the American Civil War. After Union forces took over the island in 1862, enslaved African Americans migrated there for relative freedom. The military considered them contraband and would not return them to Confederate slaveholders. The Army established the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony in 1863. In part it became an important social experiment, as a chance to develop a community of former slaves. The US government was developing policies related to the future of the formerly enslaved in freedom. Congregational chaplain Horace James was appointed as superintendent of the colony and of other contraband camps in North Carolina. With a view to making it self-sustaining, he had a sawmill built, and freedmen were allotted lands to cultivate. Those who worked for the Army were paid wages. When the United States Colored Troops were founded in 1863, many men from the colony enlisted. A corps of Northern teachers was sponsored by the American Missionary Association, and they taught hundreds of students of all ages at the colony.[5]

Geological formation and Pre-Columbian settlement

- See also Roanoke People and Croatan People.

The North Carolina Coast began to shape into its present form as the Outer Banks Barrier Islands. Previously, the North Carolina Coast had extended 50 miles eastward to the edge of the continental shelf. The melting of Northern Hemisphere Glaciers at least 14,000 years ago caused sea levels to rise. The Outer Banks and, by extension, the land of Roanoke Island began to stabilize around 6,000 B.C.[6] Roanoke Island was originally a large dune ridge facing the Atlantic coastline and therefore is not a barrier island, contrasting with Bodie Island, which exists 2 miles to the east.[7]

Archaeological discoveries at the Tillett site in Wanchese, North Carolina, have dated the human occupation of Roanoke Island's land to 8,000 B.C. At the time, Native Americans across North America were developing in the Archaic Period. Archaeologists discovered that the land of Roanoke Island was part of the Mainland when it was first inhabited by the first Native Americans. For thousands of years, the development of Native American cultures on Roanoke Island corresponded with cultures occurring in the Coastal Plain of North Carolina.

Around the year 400 AD, the area experienced an environmental transformation. The sand dune of Roanoke became disconnected from the mainland by water, and inlets in the Outer Banks turned freshwater sounds (lagoons) into brackish ecosystems. The land termed Roanoke Ridge became Roanoke Island. From approximately 460 AD to 800 AD, the Mount Pleasant Culture had a village on the Tillett Site in southern Roanoke Island, within the modern-day Wanchese township. After the year 800 AD, the village was occupied by the Colington Culture, a predecessor to the historic Roanoke tribe, who were encountered by the 1584 English Expedition.

The Roanoke people of the Tillett site had a semi-seasonal lifestyle: they inhabited the area from early Spring to early Fall, and the village was primarily based on fishing. During this yearly period, inhabitants consumed chiefly shellfish. Oysters and clams were the most common food sources, and the people left middens of shells that demonstrated their consumption. Roanoke women also gathered acorns and hackberry nuts to supplement their diets. The hunting of deer was relatively common, while the consumption of turtles was relatively rare. Lithium used for tools was maintained but not produced on the island and likely came from Bodie Island instead. Roanoke Indians had smoking pipes and used the seeds of plants such as Cleaver and Plantain for medicinal purposes. Four burials have been found at the site of Roanoke Indians of various social positions. The nobility of the culture had their skin and other soft parts of the body removed prior to burial, and after burial, preserved bodies would be transported to a temple. Tooth decay and diseases, including syphilis, were present in the community. It is extremely likely that the Roanoke had similar beliefs to the Virginian Algonquin tribes in that their great warriors and kings lived on in the afterlife, but that commoners lived only a mortal existence.[7]

English maps and written accounts attest to other indigenous villages on Roanoke Island prior to European contact. Englishman Arthur Barlowe described a palisaded town with nine houses made of cedar bark on the far north end of Roanoke Island. According to historian David Stick, this second village was based on hunting land animals. All Roanoke Island villages were likely outlying tributaries of the Secotan's capital, Dasamonguepeuk, located on the western shore of the Croatan Sound on the modern-day mainland of Dare County. At the time of contact with the English, the Roanoke were estimated to have numbered from 5,000 to 10,000 members. The Roanoke Tribe, like many other tribes in the area, was loyal to the Secotan. In 1584, Wingina was their king.[8]

The first colony

Roanoke Island was the site of the 16th-century Roanoke Colony, the first English colony in the New World. It was located in what was then called Virginia, named in honor of England's ruling monarch and "Virgin Queen", Elizabeth I.

When the English first arrived in 1584, they were accompanied by a Croatoan native and a Roanoke native called Manteo and Wanchese respectively. The two men made history as the first two Native Americans to visit the Kingdom of England as distinguished guests. For over a year they resided in London. On the return journey, the two men witnessed English pirates plundering the Spanish West Indies.

English Scientist Thomas Harriot recorded the sense of awe with which the Native Americans viewed European technology:

Many things they sawe with us ... as mathematical instruments, sea compasses ... [and] spring clocks that seemed to goe of themselves - and many other things we had - were so strange unto them, and so farre exceeded their capacities to comprehend the reason and meanes how they should be made and done, that they thought they were rather the works of gods than men.[9]

Manteo took especially great interest in Western culture, learning the English language and helping Harriot create a phonetic transcription for the Croatoan language. By contrast, Wanchese came to see the English as his captors; upon returning home in 1585, he urged his people to resist colonization at all costs. The legacy of the two Indians and their distinct roles as collaborators and antagonists to the English inspired the names of Roanoke's towns.

The first attempted settlement was headed by Ralph Lane in 1585. Sir Richard Grenville had transported the colonists to Virginia and returned to England for supplies as planned. The colonists were desperately in need of supplies, and Grenville's return was delayed.[10] While awaiting his return, the colonists relied heavily upon a local Algonquian tribe.[11] In an effort to gain more food supplies, Lane led an unprovoked attack, killing the Secotan tribe's chieftain Wingina and effectively cutting off the colony's primary food source.[11]

As a result, when Sir Francis Drake put in at Roanoke after attacking the Spanish colony of St. Augustine, the entire population abandoned the colony and returned with Drake to England. Sir Richard Grenville later arrived with supplies, only to find Lane's colony abandoned. Grenville returned to England with a Native American he named Raleigh, leaving fifteen soldiers to guard the fort. The soldiers were later killed or driven away by a Roanoke raid led by Wanchese.

In 1587, the English tried to settle Roanoke Island again, this time led by John White. At that time the Secotan Tribe and their Roanoke dependents were totally hostile to the English, but the Croatoan remained friendly. Manteo remained aligned with the English and attempted to bring the English and his Croatoan tribe together, even after the newcomers mistakenly killed his mother, who was also the Croatoan chief. After the incident Manteo was baptized into the Anglican Church. Manteo was then assigned by the English to be representative of all of the Native nations in the region; this title was mainly symbolic, as only the Croatoan nation followed Manteo.[12] John White, father of the colonist Eleanor Dare and grandfather to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World, left the colony to return to England for supplies. He expected to return to Roanoke Island within three months.

By this time, England itself was under threat of a massive Spanish invasion, and all ships were confiscated for use in defending the English Channel. White's return to Roanoke Island was delayed until 1590, by which time all the colonists had disappeared. The whereabouts of Wanchese and Manteo after the 1587 settlement attempt were also unknown. The only clue White found was the word "CROATOAN" carved into a post, as well as the letters "CRO" carved into a tree.[13][14] Before leaving the colony three years earlier, White had left instructions that if the colonists left the settlement, they were to carve the name of their destination, with a Maltese cross if they left due to danger.[15]

"Croatoan" was the name of an island to the south (modern-day Hatteras Island) where the Croatoan people, still friendly to the English, were known to live. However, foul weather kept White from venturing south to Croatoan to search for the colonists, so he returned to England. White never returned to the New World. Unable to determine exactly what happened, people referred to the abandoned settlement as "The Lost Colony."

In the book A New Voyage to Carolina (1709), the explorer John Lawson claimed that the ruins of the Lost Colony were still visible:

The first Discovery and Settlement of this Country was by the Procurement of Sir Walter Raleigh, in Conjunction with some publick-spirited Gentlemen of that Age, under the Protection of Queen Elizabeth; for which Reason it was then named Virginia, being begun on that Part called Ronoak-Island, where the Ruins of a Fort are to be seen at this day, as well as some old English Coins which have been lately found; and a Brass-Gun, a Powder-Horn, and one small Quarter deck-Gun, made of Iron Staves, and hoop'd with the same Metal; which Method of making Guns might very probably be made use of in those Days, for the Convenience of Infant-Colonies.

Lawson also claimed the natives on Hatteras island claimed to be descendants of "white people" and had inherited physical markers relating them to Europeans that no other tribe encountered on his journey shared:

A farther Confirmation of this we have from the Hatteras Indians, who either then lived on Roanoke Island, or much frequented it. These tell us, that several of their Ancestors were white People, and could talk in a Book, as we do; the Truth of which is confirm'd by gray Eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others. They value themselves extremely for their Affinity to the English, and are ready to do them all friendly Offices. It is probable, that this Settlement miscarry'd for want of timely Supplies from England; or thro' the Treachery of the Natives, for we may reasonably suppose that the English were forced to cohabit with them, for Relief and Conversation; and that in process of Time, they conform'd themselves to the Manners of their Indian Relations."

Lawson, John (1709). A New Voyage to Carolina. University of North Carolina Press (1984). pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780807841266.

From the time of the disappearance of the Lost Colony in 1587 to the Battle of Roanoke Island in 1862, Roanoke was largely isolated due to its weather and geography. Sand shoals on the Outer Banks and the North American continental shelf made navigation dangerous, and the lack of a deep-water harbor prevented Roanoke from becoming a major colonial port.

Intermediate years

Also see: Province of Carolina and Province of North Carolina

After the failure of the English Roanoke Colony, Native peoples inhabited the island for seventy more years. Archaeology from the Tilliet site indicates that the Roanoke population persisted until 1650. Written accounts indicate visible remnants of the final native presence which survived long after the end of the island's native population. A large mound 200 feet tall and 600 feet wide was recorded to exist in Wanchese in the early 1900s; now little evidence remains.[17]

The 1650 extinction date corresponds with the final war between the Powhatan Tribe and the Virginia Colony that took place in 1646. Settlers from Virginia drove the Secotan Tribe out of Outer Banks region.

Survivors of the conflict fled southwards, forming the Machapunga tribe.[18] The Machapunga fought alongside the Tuscarora Indians in the Tuscarora War (1711-1715). After their defeat in the conflict, most Machapunga settled and adapted to English lifestyles around Hyde County, North Carolina, other Machupunga fled northwards to join the Iroquois Confederation. The North Carolina descendants continued to carry some native customs until 1900 and now live in the Inner Banks of North Carolina.

Some in the former Croatoan Tribe went to Hatteras Island prior to 1650, maintained good relations with the English and were granted a reservation in 1759. Descendants of the Croatoan-Hatteras tribes later merged with English communities. The 2000 federal census found that 83 descendants from the Roanoke and Hatteras Tribe lived in Dare County. Others lived in the states of New York, Maryland, and Virginia.[19]

With Roanoke Island open for settlement, English Virginians moved from Tidewater Virginia to Northeast North Carolina's Albremarle Region. In 1665, The Carolina Charter established the colony of Carolina under a rule of landowners called the Lord Proprietors. Carolina under its original name Carolana included the territory of modern North and South Carolina.[20] Early organized English towns in North Carolina include Elizabeth City and Edenton. Pioneers crossed southwards across the Albremarle Sound to settle in Roanoke Island. They came primarily to establish fishing communities but also practiced forms of subsistence agriculture on the Northern parts of Roanoke Island. Most of the Pioneers had originally immigrated to the American Colonies from Southern English parishes such as Kent, Middlesex and the West Country. Upon the creation of the Royal British Province of North Carolina in 1729, Roanoke Island became part of Currituck County. During the rule of the Lord Proprietors, Roanoke Island had been a part of the earlier Currituck Parish.[21] It was during this time that historical families arrived including the Basnights, Daniels, Ehteridge, Owens, Tillets and others.

Ownership at first belonged to the original Lord Proprietors, who had never visited the area even as Englishmen arrived and began to build houses. The Island was owned by both Carolina Governor Sam'L Stevens and Virginian Governor Joshua Lamb. Joshua Lamb inherited the island by marrying Sam'L Steven's widow. The property was then sold and divided to a series of merchants from Boston (then part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony). Ownership by distant, far-away property holders continued until at least the 1750s. A Bostonian by the name of Bletcher Noyes gave power of attorney of his property to local William Daniels. English legal documents indicate the actual presence of settlers in 1676, with the possibility that the first Englishmen had made permanent homes much earlier.[22]

There were no incorporated towns until Manteo was founded in 1899. From the 1650s to the Civil War period, the Virginia settlers developed a distinct Hoi Toider dialect across the Outer Banks.[23] The island was ill-suited for commercial agriculture or for a deep water port and remained isolated with little interference from outsiders. The nearby community of Manns Harbor came into being as a small trading post where goods were transported across the Croatan Sound. Unlike inland North Carolina, the British authorities made no roads within or nearby Roanoke and the Tidewater region of North Carolina was avoided entirely.[24] The development of colonial Roanoke Island also depended on the natural opening and closing of inlets on Bodi and Hatteras Islands to its east. As at other times, the Island was also struck by deadly hurricanes.

During the Revolutionary War there were eight recorded encounters fought in nearby Hatteras, Ocracoke and the High Seas. These battles were between local privateers from Edenton against the British Royal Navy. The Royal Navy often had little place to rest during their coastal patrol duty. On August 15, 1776, a British patrol sent foragers to the now extinct Roanoke Inlet in modern-day Nags Head to steal cattle. The Outer Banks Independent Company who was guarding Roanoke Island killed and/or captured the entire party. This battle, while not on Roanoke Island itself, was less than three miles away.[25] Skirmishes involving ships continued until 1780 but no large land battles occurred in the area. Roanoke Island itself was largely spared from war violence and independence for the United States had little effect on local residents.[26]

Thirty years later during the War of 1812 the British Royal Navy planned for an Invasion of North Carolina's Outer Banks. The invasion was aborted on Hattaras Island because it was deemed there was nothing worthwhile for the British to occupy or pillage. The force then moved northward to attack Chesapeake Bay communities in Virginia.[27] Roanoke Island continued its isolation until authorities of the Confederate States of America hastily prepared Roanoke Island to defend Coastal North Carolina from the invading Unionist Navy and Army. After passing by Cape Hatteras Union forces attacked Roanoke Island in 1862.

Civil War years

.jpg.webp)

Main Articles: Battle of Roanoke Island and Freedmen's Colony of Roanoke Island

During the American Civil War, the Confederacy fortified the island with three forts. The Battle of Roanoke Island (February 7–8, 1862) was an incident in the Union North Carolina Expedition of January to July 1862, when Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside landed an amphibious force and took Confederate forts on the island. Afterward, the Union Army retained the three Confederate forts, renaming them for the Union generals who had commanded the winning forces: Huger became Fort Reno; Blanchard became Fort Parke; and Bartow became Fort Foster. After the Confederacy lost the forts, the Confederate Secretary of War, Judah P. Benjamin, resigned. Roanoke Island was occupied by Union forces for the duration of the war, through 1865.

The African slaves from the island and the mainland of North Carolina fled to the Union-occupied area with hopes of gaining freedom. By 1863, numerous former slaves were living on the fringe of the Union camp. The Union Army had classified the former enslaved as "contrabands," and determined not to return them to Confederate slaveholders. The freedmen founded churches in their settlement and started what was likely the first free school for blacks in North Carolina. Horace James, an experienced Congregational chaplain, was appointed by the US Army in 1863 as "Superintendent for Negro Affairs in the North Carolina District." He was responsible for the Trent River contraband camp at New Bern, North Carolina, where he was based. He also was ordered to create a self-sustaining colony at Roanoke Island[28] and thought it had the potential to be a model for a new society in which African Americans would have freedom.[29]

In addition to serving the original residents and recent migrants, the Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony was to be a refuge for the families of freedmen who enlisted in the Union Army as United States Colored Troops. By 1864, there were more than 2200 freedmen on the island.[29] Under James, the freedmen were allocated plots of land per household, and paid for work for the Army. He established a sawmill on the island and a fisheries, and began to market the many highly skilled crafts by freed people artisans. James believed the colony was a critical social experiment in free labor and a potential model for resettling freedmen on their own lands. Northern missionary teachers, mostly women from New England, journeyed to the island to teach reading and writing to both children and adults, who were eager for education. A total of 27 teachers served the island, with a core group of about six.[29]

The colony and Union troops had difficulty with overcrowding, poor sanitation, limited food and disease in its last year. The freedmen had found that the soil was too poor to support subsistence farming for so many people. In late 1865 after the end of the war, the Army dismantled the forts on Roanoke. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued an "Amnesty Proclamation," ordering the return of property by the Union Army to former Confederate landowners.[28] Most of the 100 contraband camps in the South were on former Confederate land. At Roanoke Island, the freedmen had never been given title to their plots, and the land was reverted to previous European-American owners.

Most freedmen chose to leave the island, and the Army arranged for their transportation to towns and counties on the mainland, where they looked for work. By 1867 the Army had abandoned the colony. In 1870 only 300 freedmen were living on the island. Some of their descendants still live there.[29]

Postbellum period: becoming the seat of Dare County

In the aftermath of the Civil War the area which is today Dare County was still split between Tyrell, Currituck and Hyde. Roanoke remained a part of Currituck.

In 1870 Dare County being named after the famous Virginia Dare became independent from the surrounding areas. Originally in April 1870 The Town of Roanoke Island was christened as the County Seat. In May of that year the town's name was changed to Manteo. The town of Manteo was the first place on in Dare County to have a federal post office. Roanoke Island went from being the outpost of Currituck to being the center of power in the new county. Dare County was allocated lands which included the Mainland, Roanoke Island and the beaches from Cape Hatteras upwards towards Duck.[30]

Outside Interest in the history of the Roanoke Island took hold for the first time. The State of the North Carolina protected the historical Fort Raleigh Site that had been the location of the 1584 and 1585 English expeditions. N.C State Senator Zebulon Vance attempted to build a monument in honor of the Colony in 1886 but was rebuffed by Congress because the bill would have distracted attention from Plymouth, Massachusetts.

The Town of Manteo grew as the center of business in Dare County, though it was not even the largest community in the county at the time. Buffalo City on the mainland had over 3,000 on the mainland but the community faded after the 1930s. Manteo while technically a new town was a combination of estates of landowners who had already resided on the island for two centuries. The organization of the town did spur new growth, as it became a central hub for the area. The waterfront become a bustling port with a network to Buffalo City, Edenton and Elizabeth City. Local fisherman, boat builders and landowners built fortunes whose wealth was later redistributed into new development.

There are five historically registered sites within Downtown Manteo all constructed during the turn of the 20th century. At the time Manteo carried a North American styled Queen Ann architecture combined with unique elements that reflected its coastal Environment. Churches such as Mount Olivet Methodist and Manteo Baptist were early community centers that guided local life. The construction of the island's first Court House symbolized the permanence of organized government. Manteo became Roanoke Island's only incorporated town in 1899.[31]

As seasonal tourists began to take interest Roanoke became more aligned with the national American culture. In 1917 the Pioneer Theater was established showing movies from around the country, the theater remains in existence as one of America's remaining small theaters. The transition from a wholly subsistence to a partial consumer economy began to gradually take place on the eve of the construction of the first bridge.

The first bridge

.jpg.webp)

The communities of Roanoke were transformed by the construction of the first bridge connecting the island eastwards to Nags Head in 1924. For the first time, automobiles were introduced where travel by water or horse had been previously more common. The Baum bridge marked the first time that higher level infrastructure had been brought to the island. The 1924 bridge would be the only road connection to Roanoke Island for over thirty years. Around the same time, NC 345, Roanoke Island's first paved road for automobiles, was built and covered the entire extent of the land from the marshes of Wanchese to the Northend. The north edge of NC 345 corresponded with a ferry that went to Manns Harbor on the mainland. The North Carolina department of transportation subsidized the Roanoke Island ferry in 1934 to lower ticket costs and this was origin of the modern N.C ferry system.[32]

Both Manteo in the north and Wanchese to the south were transformed by the construction of the first Nags Head bridge. Manteo which had previously been a small port reliant on trade with Elizabeth City and Edenton was now connected to a wider transportation network in both the North Carolina and Virginian Tidewater regions. The docks of Downtown Manteo began to decline as the bridge road became the center of commerce. Roanoke Island became industrialized for the first time in Wanchese. In 1936 the Wanchese Fish Cooperation was incorporated by the Daniels family as a processing and packing plant for fish, scallops and shrimp.

As Roanoke was introduced to the national market economy by the bridge, its fishing sales and local economy suffered from the Great Depression. Another blow was dealt in a 1933 Outer Banks Hurricane that made landfall in Hatteras before moving northwards toward Nova Scotia. Over 1,000 people lost their homes across Eastern North Carolina and 24 fatalities were reported. The waterfront of Manteo was destroyed by a severe fire in 1939.

In response to the crisis, the New Deal came to Roanoke Island to provide desperately needed employment and to highlight Roanoke's importance to the history of the United States. The outdoor theater play The Lost Colony written by Paul Green, began in 1936 and attracted the visit of President Franklin Roosevelt in 1937. The Lost Colony continues its performance every summer season. The onset of WWII with the German declaration of war in December, 1941 affected the island directly.

Legacy

- In 2001, Dare County erected a marble monument to the Freedmen's Colony at the Fort Raleigh Historic Site.

- It is listed as a site within the National Underground Railroad to Freedom Network of the National Park Service.

- Home and burial place of Andy Griffith

The "Mother Vine"

Possibly[33] the oldest cultivated grapevine in the world is the 400-year-old scuppernong "Mother Vine" growing on Roanoke Island.[34] The scuppernong is the state fruit of North Carolina.[35]

Education

The island is in Dare County Schools. Residents are zoned to Manteo Elementary School, Manteo Middle School, and Manteo High School.[36]

Museums on Roanoke Island

- Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

- National Wildlife Refuges Visitor Center

- North Carolina Maritime Museum on Roanoke Island

- Roanoke Island Aquarium

- Roanoke Island Festival Park

- Roanoke Marshes Lighthouse

See also

References

- Kupperman, John (1988). Captain John Smith, A selection of his writings. Wilmington VA: Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press. p. 94.

- "Archeology of the Tillett Site", Carolina Algonkian Project, 2002, accessed April 23, 2010

- Powell, William S. (1985). Paradise Preserved: A History of the Roanoke Island Historical Association. Chapel Hill: North Carolina University Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-0975-4.

- Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. pp. 21, 22.

- Patricia C. Click, "Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony" Archived 2012-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, Official Website

- Dolan, Robert; Lins, Harry; Smith, Jodi (2016). "The Outer Banks of North Carolina". USGS Science for a Changing World. 2nd Edition: 50–52.

- Sutton, David. ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE TILLETT SITE: THE FIRST FISHING COMMUNITY AT WANCHESE, ROANOKE ISLAND. Carolina Algonkian Project.

- Stick, David; Dough, Wynne; Houston, Lebame. "Indian Towns and Buildings of Eastern North Carolina". National Park Service. Gov. Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Milton, p.73

- ""History of Virginia" Page 7, 1873". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies: The Settling of North America. London, England: Penguin Books. p. 124. ISBN 9780142002100.

- "Manteo and Wanchese". www.virtualjamestown.org. 2014-01-27. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- thatgirlproductions.net. "The Roanoke Voyages". thelostcolony.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- Belval, Brian (2006). A Primary Source History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke. Rosen Classroom. p. 4. ISBN 1-4042-0669-8.

- Beers Quinn. David, Ed. The Roanoke Voyages 1584-90. Vol. 1-11. Hakluyt Society, 1955. p.615

- Lawson, John (1709). A New Voyage to Carolina. University of North Carolina Press (1984). pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780807841266.

- Sutton, David. ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE TILLETT SITE: THE FIRST FISHING COMMUNITY AT WANCHESE, ROANOKE ISLAND. Carolina Algonkian Project.

- "Carolina - The Native Americans - The Machapunga Indians". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "Algonquian Indians of North Carolina, Inc". ncalgonquians.com. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "Carolana vs. Carolina". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "Currituck County, NC - 1730 to 1790". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "Ownership of Roanoke Island since 1669". www.ncgenweb.us. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- "Hoi Toiders | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "The Royal Colony of North Carolina - Internal Roads as of 1775". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "The American Revolution in North Carolina - Roanoke Inlet". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "The American Revolution in North Carolina - The Known Battles and Skirmishes". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "North Carolina - The War of 1812". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- Click, Patricia C. "The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony" Archived 2012-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony Website, 2001, accessed November 9, 2010

- The Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, provided by National Park Service, at North Carolina Digital History: LEARN NC, accessed November 11, 2010

- "Dare County, NC - 1870". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- "Manteo, North Carolina". www.carolana.com. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- webmaster. "NCDOT: About the Ferry Division". www.ncdot.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-12-31. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- "Mother Vine". North Carolina History Project.

- Kozak, Catherine (July 14, 2008). "Mother of all vines gives birth to new wine". Virginian Pilot. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- "State Symbols and Official Adoptions | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org.

- "Attendance Zone Information". Dare County Schools. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

External links

![]() Media related to Roanoke Island at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roanoke Island at Wikimedia Commons

- Roanoke Adventure Museum

- Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, National Park Service

- Patricia C. Click, Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony

- Time Team:Fort Raleigh, North Carolina Archived 2015-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, PBS Video

- A New Voyage to Carolina, John Lawson