Rob Wagner

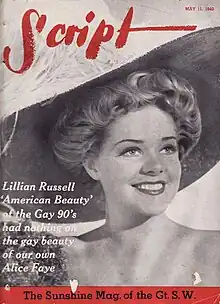

Robert Leicester Wagner (August 2, 1872 – July 20, 1942) was the editor and publisher of Script, a weekly literary film magazine published in Beverly Hills, California, between 1929 and 1949.

Rob Wagner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 2, 1872 |

| Died | July 20, 1942 (aged 69) |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, artist, film director, magazine publisher |

| Political party | Socialist |

| Spouses | Jessie Willis Brodhead (1903–1906; her death), Florence Welch (1914–1942, his death) |

Rob Wagner was a magazine writer, screenwriter, director and artist before founding the liberal magazine that focused its coverage on the film industry and California and national politics. Its leftist leanings attracted many of the best artists and writers during the Depression.

Early years

Born in Detroit, Michigan, on August 2, 1872, Wagner graduated from the University of Michigan with an engineering degree in 1894. He worked as an illustrator for the Detroit Free Press before moving to New York in 1897 to illustrate magazine covers. He served as art director for The Criterion, a literary magazine considered the forerunner to The New Yorker. His illustrations of coverage of the Spanish–American War and the rising star of Theodore Roosevelt increased circulation and gave considerable weight to the magazine's political commentary and coverage. ]Rob Wagner wrote for the Saturday Evening Post, The Western Comrade and Liberty magazines among other publications.

In 1901, he moved to London to work as an illustrator for the Historians' History of the World. He returned a year later to New York to illustrate the Encyclopædia Britannica. He returned to Detroit in 1903 to marry Jessie Brodhead, and then moved to Paris to study art. In 1903–04 he studied at Academies Julian and Delacluse, initially working in charcoal before focusing on oil portraits. Toward the end of his studies, he joined the Paris art studio of Robert MacCameron where his work in oils greatly improved. When he returned to Detroit he took commissions to paint portraits, many of them life-size, of the city's high society families.

In 1906, he moved to Santa Barbara, California, when Jessie, who was suffering from tuberculosis, could no longer endure the harsh Michigan winters. In Santa Barbara Wagner continued taking commissions for portraits. The couple had two sons, but Jessie's health deteriorated rapidly, and she died on August 19 at the age of 28. With two young motherless boys, Wagner left them with his own mother, Mary Leicester Wagner, in Santa Barbara and opened a studio on South Figueroa Street in Los Angeles to pursue his art.

Motion picture background

Instead, he became intrigued with motion pictures as an art form. He wrote his first scenario for The Artist's Sons in 1911. The semi-autobiographical two-reel film produced by Selig Studios explored the bohemian lifestyle of a Los Angeles artist and his two young sons. Wagner's own sons, Leicester ("Les") and Thornton, played themselves in the film, which also featured dozens of Wagner's original oil portraits. In this period, Wagner taught for a number of years at the Manual Arts High School, where his students included Frank Capra, Jimmy Doolittle[1] and Leland Curtis.

Wagner went on to write scenarios for Charles Ray, Hal Roach and Mack Sennett. For Hal Roach he wrote and directed films for Will Rogers, including Two Wagons, Both Covered (1924). He also directed Rogers in Our Congressman, Goin' to Congress and High Brow Stuff, also in 1924. Toward the end of his contract with Roach in 1924, he served a stint as assistant director in the Our Gang comedies. He also was under contract in 1922 and 1923 to write scenarios and titles for Paramount Studios and in 1926 and 1927 for Universal Studios where he was a co-writer on The Collegians (1926). He also wrote scenarios for film comedian Maurice "Lefty" Flynn for Robertson-Cole Pictures Corporation. He also wrote scenarios for Constrance Binney at Realart, a low-budget film studio.[2]

In 1914, Wagner married Kansas City newspaperwoman Florence Welch, who told her new husband that he could make a better living writing about the motion picture industry than working as an artist. He covered the film industry writing for the Saturday Evening Post, Collier's, Liberty, Photoplay and other magazines. His series of articles on the film industry in The Saturday Evening Post resulted in the book Film Folk (1918), one of the first serious examinations of the movie business.

Motion Picture & Television Fund

In 1921, Wagner, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith co-founded the Motion Picture Relief Fund, which later became the Motion Picture & Television Fund, to provide financial aid to film industry workers who fell on hard times. The creation of the program eventually led to the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital retirement facility in Woodland Hills. Acquisition of the 48 acres (190,000 m2) of land and building started in 1940.

Wagner was an original member of the Board of Trustees. Other members included Harold Lloyd, William S. Hart, Jesse L. Lasky, Rupert Hughes, Irving Thalberg and Mae Murray among others.

Script

The Wagners founded Script in February 1929 and enlisted noted writers and film people to contribute articles without pay.[3] Edgar Rice Burroughs, Walt Disney, William Saroyan, Ogden Nash, Dalton Trumbo, Chaplin, Hughes, William DeMille, Ray Bradbury, Leo Politi and Stanton MacDonald-Wright among others wrote for the magazine. Bradbury was a regular contributor with a series of short stories from about 1940 through 1947. MacDonald-Wright provided art reviews. Gladys Robinson, wife of actor Edward G. Robinson, wrote a Hollywood gossip column. Script was liberal, witty and fond of tweaking the noses of the country's movers and shakers.

Leftist leanings

Wagner, a Socialist, was a progressive advocate dating to at least 1900 during his tenure as art director at The Criterion. The magazine and its theater group, The Criterion Theater, was a magnet for artists and writers that embraced individualism and Socialism. By 1914, he helped establish with Job Harriman the Llano del Rio cooperative colony in California's Antelope Valley. The project ultimately failed. During this period he served as associate editor for Los Angeles-based Western Comrade magazine, which offered a mix of socialist dogma, labor-related film news, advocacy on the women's suffrage movement, and profiles on artists and writers. The magazine also featured leftist writers Emanuel Haldeman-Julius and Frank E. Wolfe. Through the period of World War I to the early 1920s he was often the subject of Department of Justice scrutiny for his Socialist and pro-Bolshevik activities.

Wagner also sent his sons to Boyland, an avant-garde boarding school with a progressive, if not unorthodox, approach to education. Pacifist Prynce Hopkins operated the school. However, Hopkins was arrested under the Espionage Act in 1918 for making an anti-war speech in Los Angeles. Hopkins was charged and pleaded guilty in federal court of interfering with military recruitment. Federal authorities interrogated Wagner about Hopkins. Although Wagner defended Hopkins, it put Wagner in the spotlight of the government's attempt to crush the anti-war movement. His defense of Hopkins cost him his job as a teacher at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles.[4]

Around 1915 Wagner had become friends with Charlie Chaplin and was soon employed as the comedian's part-time secretary. Chaplin was eligible for the draft in both the United States and England during World War I, but was rejected for military service because he was too small. Yet he was under intense scrutiny for failing to support the war effort. Wagner waged a publicity campaign on Chaplin's behalf to demonstrate the actor's support. Wagner also helped organize a War Bond tour that included Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.[4]

Shortly before the Liberty Bond tour began some of Wagner's friends informed on him to the US Bureau of Investigation that he supported Germany during the war and expressed his strong opposition to America's entry into the conflict. Sisters Ruth Sterry, a Los Angeles newspaperwoman active in the suffragette movement, and Nora Sterry, a school principal, attended round table discussions with Wagner at his Los Angeles art studio. They reported to federal authorities that Wagner voiced support for Germany. Ruth Sterry claimed that Wagner told her sister that the United States should surrender if Germany invaded. Her allegations were never proven. Wagner's longtime friend, the artist Elmer Wachtel, provided agents with a letter Wagner wrote, which contained anti-war statements and sympathy for the German government. The Bureau of Investigation and the War Department's Military Intelligence Branch attempted to determine whether Wagner was a German agent. Undercover operatives conducted around-the-clock surveillance of Wagner as the Chaplin party swung through the Southern states during the tour. Agents attempted to recruit Douglas Fairbanks as an informant, but there is no evidence to suggest the actor agreed to the plan. Agents also hired a young woman to seduce Wagner to gain access to his personal diaries while the Chaplin party stayed at a New Orleans hotel, but the plan was never carried out. Ultimately, however, agents obtained Wagner's diaries, but found no evidence that he was a German spy.[5]

In November and December 1919, he was summoned before a Los Angeles County Grand Jury on charges of sedition for his vocal opposition to America's entry into the European war, his association with the radical International Workers of the World (IWW) and his sympathies for Germany. The grand jury did not deliver an indictment due to insufficient evidence.[5]

Wagner also introduced Chaplin to leftists Max Eastman and Upton Sinclair, and between the three men helped influence Chaplin's left-leaning worldview. Chaplin often participated in roundtable political and moral discussions of the war, which was sponsored by the Severance Club that consisted of writers and film people, including Wagner.[4]

Script was a supporter of Franklin Roosevelt's policies. As the world teetered on the brink of war, it often took a pacifist tone. And its wartime domestic coverage took on unpopular causes such as defending the rights of Mexican-Americans during the Los Angeles Zoot Suit riots, the postwar resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan[6] and questioning the wisdom of interning Japanese-Americans. Wagner had written extensively for Socialist publications in the first decades of the 20th century and his liberal views were reflected in his columns and interviews with leftists Upton Sinclair, Max Eastman and William C. deMille. The magazine also conducted extensive interviews with Communist revolutionary Leon Trotsky in 1938.[7] Script also published articles written by blacklisted screenwriters, including Dalton Trumbo and Gordon Kahn.[8]

Politi, the magazine's art director, often used the illustrations of his Mexican child characters, Pancho and Rosa, to advocate pacifist and anti-fascist arguments.[9]

Upton Sinclair association

During the 1934 California gubernatorial campaign, Script gave considerable editorial space to Upton Sinclair's candidacy while the rest of the film community waged a smear campaign against him by claiming his radical economic policies would bankrupt the movie studios. During Sinclair's campaign for governor, his balanced coverage nearly sank the magazine as advertisers and subscribers began to pull out. Keeping a low profile, Wagner also worked on Sinclair's EPIC (End Poverty in California) campaign writing the text for pamphlets and designing the organization's logo.

The magazine's free-thinking attitudes appealed to most of its readers. The magazine, with a circulation that never rose above 50,000, was illustrated with cartoons from various contributors. The art often were unrelated to the articles and only occasional photographs beyond the covers were used.

Script's demise

Wagner died of a heart attack on July 20, 1942, less than two weeks before his 70th birthday, in Santa Barbara. His son, Les, a reporter for the original Los Angeles Daily News and later a war correspondent for the Office of War Information in India, took over the editing duties until his India assignment in 1944. Under Les Wagner, the magazine took on a more news-oriented approach. It took up populist causes and critiqued local media, often criticizing as fascist Hearst newspaper coverage and editorials on Constitutional issues and the civil rights of Mexican- and Japanese-Americans.[10] In 1943, Script published editorials defending Charlie Chaplin, who was named as a defendant in a paternity lawsuit by Joan Barry, while Los Angeles newspapers were critical of the filmmaker. Blood tests ultimately determined that Chaplin did not father Barry's child. In 1944–45, Wagner filed dispatches for Script from Calcutta, India, on U.S. and British forces in the China-Burma-India Theater.

Florence Wagner kept the magazine going, but it lost much of its punch because the personality of the publication was driven by Rob Wagner. Wagner continued championing leftist causes by often profile left-leaning actors and directors. For example, Script profiled actor Angela Lansbury, who wrote a first-person account of her father, Edgar Lansbury, leader of the Labour Party in the United Kingdom. In March 1947, she sold the magazine to Robert Smith, the general manager of the original Los Angeles Daily News. Smith brought in new writers that added new voices and a much needed lift in film comment. Smith also arranged to have Salvador Dalí contribute cover illustrations. While the publication's circulation rose to its pre-war levels of 50,000, it failed to attract the necessary advertising. It folded in 1949. Les Wagner died in 1965 in South Laguna Beach, California. Florence Wagner died in 1971 in La Jolla, California.[9]

Partial filmography

- The Artist's Sons (1911) (writer)

- From Dusk to Dawn (1913) (set decorator)

- Our Wonderful Schools (1915) (director / writer)

- Mabel, Fatty and the Law (1915) (writer)

- A Yoke of Gold (1916) (writer)

- A Dog's Life (1918) (actor)

- The Mite of Love (1919) (actor)

- Dangerous Business (1920) (writer)

- R.S.V.P. (1921) (writer)

- Smudge (1922) (writer)

- A Trip to Paramountown (1922) (titles)

- Gee Whiz, Genevieve (1924) (additional gags)

- Two Wagons, Both Covered (1924) (director / writer)

- Going to Congress (1924) (director)

- High Brow Stuff (1924) (director)

- Our Congressman (1924) (director)

- It's a Bear (1924) (assistant director)

- Fair Week (1924) (director)

- Smilin' at Trouble (1925) (writer)

- Heads Up (1925) (writer)

- The Collegians (1926) (writer)

- So This Is Paris (1926) (titles)

- Ladies at Ease (1927) (writer)

- Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly? (1928) (writer)

References

- "Biography for Rob Wagner". IMDb: The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- Wagner, Rob Leicester (June 1, 2016). Hollywood Bohemia: The Roots of Progressive Politics in Rob Wagner's Script. Janaway. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-59641-369-6.

- "Seventeen Years: Feb. 1929-Feb. 1946" By Florence Wagner, Rob Wagner's Script, Feb. 2, 1946

- Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles by Beth Gates Warren

- FBI files

- "The Hooded Brethren Ride Again" By M.J. King, Rob Wagner's Script, June 8, 1946

- "An Exile in Mexico" By Gladys Lloyd Robinson, Rob Wagner's Script, September 10, 1938

- "The Russian Menace" By Dalton Trumbo, Rob Wagner's Script, May 25, 1946

- Rob Wagner's Script Archive

- "American-Japanese Heroes" by Les Wagner, Rob Wagner's Script, January 5, 1946

Sources

- The Best of Rob Wagner's Script by Anthony Slide (1985)

- Tramp: The Life of Charlie Chaplin by Joyce Milton (1998)

- Rob Wagner's Beverly Hills Script (Vol. I)

- Rob Wagner's Script (Vols. II–IV)

- Western Comrade (1914)

- Hollywood Bohemia: The Roots of Progressive Politics in Rob Wagner's Script by Rob Leicester Wagner (2016) (ISBN 978-1-59641-369-6)