Mary Pickford

Gladys Marie Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian actress resident in the U.S., and also producer, screenwriter and film studio founder, who was a pioneer in the US film industry with a Hollywood career that spanned five decades.

Mary Pickford | |

|---|---|

Pickford in 1910 | |

| Born | Gladys Marie Smith[1] April 8, 1892 |

| Died | May 29, 1979 (aged 87) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Burial place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Citizenship | British subject (1892–1978) Canada (1978–1979)[2] |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1900–1955 |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Website | Mary Pickford Foundation |

| Signature | |

| |

Pickford alongside her future husband, actor-producer Douglas Fairbanks, founded Pickford–Fairbanks Studios and United Artists, and was one of the 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.[3] Pickford is considered to be one of the most recognisable women in history.[4]

Known as "America's Sweetheart" during the silent film era, she is named on the list of the AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars as the 24th-top female star from the Classical Hollywood Cinema era[5][6][7] and the "girl with the curls".[7]

Pickford was one of the Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood and a significant figure in the development of film acting. She was one of the earliest stars to be billed under her own name,[8] and was one of the most popular actresses of the 1910s and 1920s, earning the nickname "Queen of the Movies". She is credited with having defined the ingénue type in cinema.[9]

She was awarded the second Academy Award for Best Actress for her first sound film role in Coquette (1929). By the late 1920s Pickford's career went into decline. She received an Academy Honorary Award in 1976 in consideration of her contributions to American cinema.

Early life

Mary Pickford was born Gladys Marie Smith in 1892, at 211 University Avenue Toronto, Ontario.[1] now the location of the Hospital for Sick Children. Her father, John Charles Smith, was the son of English Methodist immigrants, and worked a variety of odd jobs. Her mother, Charlotte Hennessey, was of Irish Catholic descent and worked for a time as a seamstress. She had two younger siblings, both actors. Charlotte was billed as "Lottie Pickford" (born 1893) and John Charles Jr. was billed as "Jack Pickford" (born 1896). To please her husband's relatives, Pickford's mother baptized her children as Methodists, the religion of their father. John Charles Sr. was an alcoholic; he abandoned the family and died on February 11, 1898, from a fatal blood clot caused by a workplace accident when he was a purser with Niagara Steamship.[1]

When Gladys was four years old, her household was under infectious quarantine as a public health measure. Their devoutly Catholic maternal grandmother (Catherine Faeley Hennessey) asked a visiting Roman Catholic priest to baptize the children. Pickford was at this time baptized as Gladys Marie Smith.[10][11]

After being widowed in 1899, Charlotte Smith began taking in boarders, one of whom was a Mr. Murphy, the theatrical stage manager for Cummings Stock Company, who soon suggested that Gladys, then age seven, and Lottie, then age six, be given two small theatrical roles—Gladys portrayed a girl and a boy, while Lottie was cast in a silent part in the company's production of The Silver King at Toronto's Princess Theatre (destroyed by fire in 1915, rebuilt, demolished in 1931), while their mother played the organ.[12][1] Pickford subsequently acted in many melodramas with Toronto's Valentine Stock Company, finally playing the major child role in its version of The Silver King. She capped her short career in Toronto with the starring role of Little Eva in the Valentine production of Uncle Tom's Cabin, adapted from the 1852 novel.[1]

Career

Early years

_digital_restoration.jpg.webp)

By the early 1900s, theatre had become a family enterprise. Gladys, her mother, and two younger siblings toured the United States by rail, performing in third-rate companies and plays. After six impoverished years, Pickford allowed one more summer to land a leading role on Broadway, planning to quit acting if she failed. In 1905 she played the boy Freckles in Hal Reid's The Gypsy Girl on tour, and at the Star Theatre on Broadway.[13] In 1906 Gladys, Lottie and Jack Smith supported singer Chauncey Olcott on Broadway in Edmund Burke.[14] Gladys finally landed a supporting role in a 1907 Broadway play, The Warrens of Virginia. The play was written by William C. deMille, whose brother, Cecil, appeared in the cast. David Belasco, the producer of the play, insisted that Gladys Smith assume the stage name Mary Pickford.[15] After completing the Broadway run and touring the play, however, Pickford was again out of work.

On April 19, 1909, the Biograph Company director D. W. Griffith screen-tested her at the company's New York studio for a role in the nickelodeon film Pippa Passes. The role went to someone else but Griffith was immediately taken with Pickford. She quickly grasped that movie acting was simpler than the stylized stage acting of the day. Most Biograph actors earned $5 a day but, after Pickford's single day in the studio, Griffith agreed to pay her $10 a day against a guarantee of $40 a week.[16]

Pickford, like all actors at Biograph, played both bit parts and leading roles, including mothers, ingénues, charwomen, spitfires, slaves, Native Americans, spurned women, and a prostitute. As Pickford said of her success at Biograph:

I played scrubwomen and secretaries and women of all nationalities ... I decided that if I could get into as many pictures as possible, I'd become known, and there would be a demand for my work.

She appeared in 51 films in 1909—almost one a week—with her first starring role being in The Violin Maker of Cremona opposite future husband Owen Moore.[3] While at Biograph, she suggested to Florence La Badie to "try pictures", invited her to the studio and later introduced her to D. W. Griffith, who launched La Badie's career.[17]

In January 1910, Pickford traveled with a Biograph crew to Los Angeles. Many other film companies wintered on the West Coast, escaping the weak light and short days that hampered winter shooting in the East. Pickford added to her 1909 Biographs (Sweet and Twenty, They Would Elope, and To Save Her Soul, to name a few) with films made in California.

Actors were not listed in the credits in Griffith's company. Audiences noticed and identified Pickford within weeks of her first film appearance. Exhibitors, in turn, capitalized on her popularity by advertising on sandwich boards that a film featuring "The Girl with the Golden Curls", "Blondilocks", or "The Biograph Girl" was inside.[18]

Pickford left Biograph in December 1910. The following year, she starred in films at Carl Laemmle's Independent Moving Pictures Company (IMP). IMP was absorbed into Universal Pictures in 1912, along with Majestic. Unhappy with their creative standards, Pickford returned to work with Griffith in 1912. Some of her best performances were in his films, such as Friends, The Mender of Nets, Just Like a Woman, and The Female of the Species. That year, Pickford also introduced Dorothy and Lillian Gish—whom she had befriended as new neighbors from Ohio[19]—to Griffith,[1] and each became major silent film stars, in comedy and tragedy, respectively. Pickford made her last Biograph picture, The New York Hat, in late 1912.

She returned to Broadway in the David Belasco production of A Good Little Devil (1912). This was a major turning point in her career. Pickford, who had always hoped to conquer the Broadway stage, discovered how deeply she missed film acting. In 1913, she decided to work exclusively in film. The previous year, Adolph Zukor had formed Famous Players in Famous Plays. It was later known as Famous Players–Lasky and then Paramount Pictures, one of the first American feature film companies.

Pickford left the stage to join Zukor's roster of stars. Zukor believed film's potential lay in recording theatrical players in replicas of their most famous stage roles and productions. Zukor first filmed Pickford in a silent version of A Good Little Devil. The film, produced in 1913, showed the play's Broadway actors reciting every line of dialogue, resulting in a stiff film that Pickford later called "one of the worst [features] I ever made ... it was deadly".[1] Zukor agreed; he held the film back from distribution for a year.

Pickford's work in material written for the camera by that time had attracted a strong following. Comedy-dramas, such as In the Bishop's Carriage (1913), Caprice (1913), and especially Hearts Adrift (1914), made her irresistible to moviegoers. Hearts Adrift was so popular that Pickford asked for the first of her many publicized pay raises based on the profits and reviews.[20] The film marked the first time Pickford's name was featured above the title on movie marquees.[20] Tess of the Storm Country was released five weeks later. Biographer Kevin Brownlow observed that the film "sent her career into orbit and made her the most popular actress in America, if not the world".[20]

Her appeal was summed up two years later by the February 1916 issue of Photoplay as "luminous tenderness in a steel band of gutter ferocity".[1] Only Charlie Chaplin, who slightly surpassed Pickford's popularity in 1916,[21] had a similarly spellbinding pull with critics and the audience. Each enjoyed a level of fame far exceeding that of other actors. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Pickford was believed to be the most famous woman in the world, or, as a silent-film journalist described her, "the best known woman who has ever lived, the woman who was known to more people and loved by more people than any other woman that has been in all history".[1]

Stardom

Pickford starred in 52 features throughout her career. On June 24, 1916, Pickford signed a new contract with Zukor that granted her full authority over production of the films in which she starred,[22] and a record-breaking salary of $10,000 a week.[23] In addition, Pickford's compensation was half of a film's profits, with a guarantee of $1.04 million (US$21,170,000 in 2023),[24] making her the first actress to sign a million-dollar contract.[3] She also became vice-president of Pickford Film Corporation.[3]

Occasionally, she played a child, in films such as The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917), Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917), Daddy-Long-Legs (1919), and Pollyanna (1920). Pickford's fans were devoted to these "little girl" roles, but they were not typical of her career.[1] Due to her lack of a normal childhood, she enjoyed making these pictures. Given how small she was at under five feet, and her naturalistic acting abilities, she was very successful in these roles. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., when he first met her in person as a boy, assumed she was a new playmate for him, and asked her to come and play trains with him, which she obligingly did.[25]

In August 1918, Pickford's contract expired and, when refusing Zukor's terms for a renewal, she was offered $250,000 to leave the motion picture business. She declined, and went to First National Pictures, which agreed to her terms.[26] In 1919, Pickford, along with D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks, formed the independent film production company United Artists. Through United Artists, Pickford continued to produce and perform in her own movies; she could also distribute them as she chose. In 1920, Pickford's film Pollyanna grossed around $1.1 million.[27] The following year, Pickford's film Little Lord Fauntleroy was also a success, and in 1923, Rosita grossed over $1 million as well.[27] During this period, she also made Little Annie Rooney (1925), another film in which Pickford played a child, Sparrows (1926), which blended the Dickensian with newly minted German expressionist style, and My Best Girl (1927), a romantic comedy featuring her future husband Charles "Buddy" Rogers.

The arrival of sound was her undoing. Pickford underestimated the value of adding sound to movies, claiming that "adding sound to movies would be like putting lipstick on the Venus de Milo".[27]

She played a reckless socialite in Coquette (1929), her first talkie,[28] a role for which her famous ringlets were cut into a 1920s bob. Pickford had already cut her hair in the wake of her mother's death in 1928. Fans were shocked at the transformation.[29] Pickford's hair had become a symbol of female virtue, and when she cut it, the act made front-page news in The New York Times and other papers. Coquette was a success and won her an Academy Award for Best Actress,[30] although this was highly controversial.[31] The public failed to respond to her in the more sophisticated roles. Like most movie stars of the silent era, Pickford found her career fading as talkies became more popular among audiences.[30]

Her next film, The Taming of The Shrew, made with husband Douglas Fairbanks, was not well received at the box office.[32] Established Hollywood actors were panicked by the impending arrival of the talkies. On March 29, 1928, The Dodge Brothers Hour was broadcast from Pickford's bungalow, featuring Fairbanks, Chaplin, Norma Talmadge, Gloria Swanson, John Barrymore, D. W. Griffith, and Dolores del Río, among others. They spoke on the radio show to prove that they could meet the challenge of talking movies.[33]

A transition in the roles Pickford selected came when she was in her late thirties, no longer able to play the children, teenage spitfires, and feisty young women so adored by her fans, and not suited for the glamorous and vampish heroines of early sound. In 1933, she underwent a Technicolor screen test for an animated/live-action film version of Alice in Wonderland, but Walt Disney discarded the project when Paramount released its own version of the book. Only one Technicolor still of her screen test still exists.

She retired from film acting in 1933 following three costly failures with her last film appearance being Secrets.[3][34] She appeared on stage in Chicago in 1934 in the play The Church Mouse and went on tour in 1935, starting in Seattle with the stage version of Coquette.[3] She also appeared in a season of radio plays for NBC in 1935 and CBS in 1936.[3] In 1936 she became vice-president of United Artists[34] and continued to produce films for others, including One Rainy Afternoon (1936), The Gay Desperado (1936), Sleep, My Love (1948; with Claudette Colbert), and Love Happy (1949), with the Marx Brothers.[1]

The film industry

Pickford used her stature in the movie industry to promote a variety of causes. Although her image depicted fragility and innocence, she proved to be a strong businesswoman who took control of her career in a cutthroat industry.[35]

During World War I she promoted the sale of liberty bonds, making an intensive series of fund-raising speeches, beginning in Washington, D.C., where she sold bonds alongside Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Theda Bara, and Marie Dressler. Five days later she spoke on Wall Street to an estimated 50,000 people. Though Canadian-born, she was a powerful symbol of American culture, kissing the American flag for cameras and auctioning one of her world-famous curls for $15,000. In a single speech in Chicago, she sold an estimated five million dollars' worth of bonds. She was christened the U.S. Navy's official "Little Sister"; the Army named two cannons after her and made her an honorary colonel.[1]

In 1916, Pickford and Constance Adams DeMille, wife of director Cecil B. DeMille, helped found the Hollywood Studio Club, a dormitory for young women involved in the motion picture business.[3] At the end of World War I, Pickford conceived of the Motion Picture Relief Fund, an organization to help financially needy actors. Leftover funds from her work selling Liberty Bonds were put toward its creation, and in 1921, the Motion Picture Relief Fund (MPRF) was officially incorporated, with Joseph Schenck voted its first president and Pickford its vice president. In 1932, Pickford spearheaded the "Payroll Pledge Program", a payroll-deduction plan for studio workers who gave one half of one percent of their earnings to the MPRF. As a result, in 1940, the Fund was able to purchase land and build the Motion Picture Country House and Hospital, in Woodland Hills, California.[1]

An astute businesswoman, Pickford became her own producer within three years of her start in features. According to her Foundation, "she oversaw every aspect of the making of her films, from hiring talent and crew to overseeing the script, the shooting, the editing, to the final release and promotion of each project". She demanded (and received) these powers in 1916, when she was under contract to Zukor's Famous Players in Famous Plays (later Paramount). Zukor acquiesced to her refusal to participate in block-booking, the widespread practice of forcing an exhibitor to show a bad film of the studio's choosing to also be able to show a Pickford film. In 1916, Pickford's films were distributed, singly, through a special distribution unit called Artcraft. The Mary Pickford Corporation was briefly Pickford's motion-picture production company.[36]

In 1919, she increased her power by co-founding United Artists (UA) with Charlie Chaplin, D. W. Griffith, and her soon-to-be husband, Douglas Fairbanks. Before UA's creation, Hollywood studios were vertically integrated, not only producing films but forming chains of theaters. Distributors (also part of the studios) arranged for company productions to be shown in the company's movie venues. Filmmakers relied on the studios for bookings; in return they put up with what many considered creative interference.

United Artists broke from this tradition. It was solely a distribution company, offering independent film producers access to its own screens as well as the rental of temporarily unbooked cinemas owned by other companies. In 1919, Pickford established The Mary Pickford Company, that was devoted exclusively to producing films distributed by United Artists. With the film Pollyanna being Mary's first film distributed by The United Artists.[37] Pickford and Fairbanks produced and shot their films after 1920 at the jointly owned Pickford-Fairbanks studio on Santa Monica Boulevard. The producers who signed with UA were true independents, producing, creating and controlling their work to an unprecedented degree. As a co-founder, as well as the producer and star of her own films, Pickford became the most powerful woman who has ever worked in Hollywood. By 1930, Pickford's acting career had largely faded.[30] After retiring three years later, however, she continued to produce films for United Artists. She and Chaplin remained partners in the company for decades. Chaplin left the company in 1955, and Pickford followed suit in 1956, selling her remaining shares for $3 million.[36]

She had bought the rights to many of her early silent films with the intention of burning them on her death, but in 1970 she agreed to donate 50 of her Biograph films to the American Film Institute.[28] In 1976, she received an Academy Honorary Award for her contribution to American film.[28]

Personal life

Pickford was married three times. She married Owen Moore, an Irish-born silent film actor, on January 7, 1911. It is rumored she became pregnant by Moore in the early 1910s and had a miscarriage or an abortion. Some accounts suggest this resulted in her later inability to have children.[1] The couple's marriage was strained by Moore's alcoholism, insecurity about living in the shadow of Pickford's fame, and bouts of domestic violence.[38] The couple lived together on-and-off for several years.[39]

Pickford became secretly involved in a relationship with Douglas Fairbanks. They toured the U.S. together in 1918 to promote Liberty Bond sales for the World War I effort. Around this time, Pickford also suffered from the flu during the 1918 flu pandemic.[40] Pickford divorced Moore on March 2, 1920, after she agreed to his $100,000 demand for a settlement ($1.5 million in 2023, adjusted for inflation).[41] She married Fairbanks just days later on March 28, 1920, in what was described as the "marriage of the century" and they were referred to as the King and Queen of Hollywood.[3] They went to Europe for their honeymoon; fans in London and in Paris caused riots trying to get to the famous couple. The couple's triumphant return to Hollywood was witnessed by vast crowds who turned out to hail them at railway stations across the United States.

The Mark of Zorro (1920) and a series of other swashbucklers gave the popular Fairbanks a more romantic, heroic image. Pickford continued to epitomize the virtuous but fiery girl next door. Even at private parties, people instinctively stood up when Pickford entered a room; she and her husband were often referred to as "Hollywood royalty". Their international reputations were broad. Foreign heads of state and dignitaries who visited the White House often asked if they could also visit Pickfair, the couple's mansion in Beverly Hills.[15]

Dinners at Pickfair became celebrity events. Charlie Chaplin, Fairbanks' best friend, was often present. Other guests included George Bernard Shaw, Albert Einstein, Elinor Glyn, Helen Keller, H. G. Wells, Lord Mountbatten, Fritz Kreisler, Amelia Earhart, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Noël Coward, Max Reinhardt, Baron Nishi, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko,[42] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Austen Chamberlain, Sir Harry Lauder, and Meher Baba, among others. However, the public nature of Pickford's second marriage strained it to the breaking point. Both she and Fairbanks had little time off from producing and acting in their films. They were also constantly on display as America's unofficial ambassadors to the world, leading parades, cutting ribbons, and making speeches. When their film careers both began to flounder at the end of the silent era, Fairbanks' restless nature prompted him to overseas travel (something which Pickford did not enjoy). When Fairbanks' romance with Sylvia, Lady Ashley became public in the early 1930s, he and Pickford separated. They divorced January 10, 1936. Fairbanks' son by his first wife, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., claimed his father and Pickford long regretted their inability to reconcile.[1]

On June 24, 1937, Pickford married her third and last husband, actor and band leader Charles "Buddy" Rogers. They adopted two children: Roxanne (born 1944, adopted 1944) and Ronald Charles (born 1937, adopted 1943, a.k.a. Ronnie Pickford Rogers). A PBS American Experience documentary described Pickford's relationship with her children as tense. She criticized their physical imperfections, including Ronnie's small stature and Roxanne's crooked teeth. Both children later said their mother was too self-absorbed to provide real maternal love. In 2003, Ronnie recalled that "Things didn't work out that much, you know. But I'll never forget her. I think that she was a good woman."[43]

Political views

Pickford supported Thomas Dewey in the 1944 United States presidential election, Barry Goldwater in the 1964 United States presidential election[44] and Ronald Reagan in his race for governor in 1966.[45] She was a charter member of the Hollywood Republican Committee.[46]

Later years and death

After retiring from the screen, Pickford became an alcoholic, as her father had been. Her mother Charlotte died of breast cancer in March 1928. Her siblings, Lottie and Jack, died of alcohol-related causes in 1936 and 1933. These deaths, her divorce from Fairbanks, and the end of silent films left Pickford deeply depressed. Her relationship with her adopted children, Roxanne and Ronald, was turbulent at best. Pickford withdrew and gradually became a recluse, remaining almost entirely at Pickfair and allowing visits only from Lillian Gish, her stepson Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and a few select others.

In 1955, she published her memoirs, Sunshine and Shadows.[28] She had previously published Why Not Try God in 1934, an essay on spirituality and personal growth, My Rendevouz of Life (1935), an essay on death and her belief in an afterlife and also a novel in 1935, The Demi-Widow.[34][3]

In the mid-1960s, Pickford often received visitors only by telephone, speaking to them from her bedroom. Charles "Buddy" Rogers often gave guests tours of Pickfair, including views of a genuine western bar Pickford had bought for Douglas Fairbanks, and a portrait of Pickford in the drawing room. A print of this image now hangs in the Library of Congress.[36] When Pickford received an Academy Honorary Award in 1976, the Academy sent a TV crew to her house to record her short statement of thanks—offering the public a very rare glimpse into Pickfair Manor.[47] Charitable events continued to be held at Pickfair, including an annual Christmas party for blind war veterans, mostly from World War I.[3]

_munitions_factory_(I0004930).tif.jpg.webp)

Pickford believed that she had ceased to be a British subject when she married Fairbanks, an American citizen, in 1920.[48] and thus presumably had not acquired Canadian citizenship when it was first created in 1947. However, Pickford held and traveled under a British/Canadian passport which she renewed regularly at the British/Canadian consulates in Los Angeles, and she did not take out papers for American citizenship. She also owned a house in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Toward the end of her life, Pickford made arrangements with the Canadian Department of Citizenship to officially acquire Canadian citizenship because she wished to "die as a Canadian". Canadian authorities were not sure that she had ever lost her Canadian citizenship, given her passport status, but her request was approved and she officially became a Canadian citizen.[49][50]

On May 29, 1979, Pickford died at a Santa Monica, California, hospital of complications from a cerebral hemorrhage she had suffered the week before.[51] She was interred in the Garden of Memory of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park cemetery in Glendale, California.

Legacy

- Pickford was awarded a star in the category of motion pictures on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6280 Hollywood Blvd.[52]

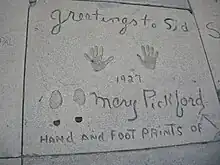

- Her handprints and footprints are displayed at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, California. Although the theater's official account credits Norma Talmadge as having inspired the theater’s tradition of putting footprints in concrete when she accidentally stepped into wet concrete,[53] in a short interview during the September 13, 1937, Lux Radio Theatre broadcast of a radio adaptation of A Star Is Born, Sid Grauman related another version of how he got the idea to put hand and foot prints in the concrete, involving Pickford. He said it was "pure accident. I walked right into it. While we were building the theatre, I accidentally happened to step in some soft concrete. And there it was. So, I went to Mary Pickford immediately. Mary put her foot into it."[54]: 194

- She is represented in Hergé's Tintin in America.[55]

- The Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study at 1313 Vine Street in Hollywood, constructed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, opened in 1948 as a radio and television studio facility.

- The Mary Pickford Theater at the James Madison Memorial Building of the Library of Congress is named in her honor.[36]

- A prohibition-era cocktail was named in her honor.

- The Mary Pickford Auditorium at Claremont McKenna College is named in her honor.

- In 1948, Mary Pickford built a seven-bedroom, eight-bathroom, 6,050-square-foot (562 m2) estate on 2.12 acres (8,600 m2) at the B Bar H Ranch, California, where she lived and then later sold.[56]

- A first-run movie theatre in Cathedral City, California, is called The Mary Pickford Theatre, which was established on May 25, 2001.[57] The theater is a grand one with several screens and is built in the shape of a Spanish Cathedral, complete with bell tower and three-story lobby. The lobby contains a historic display with original artifacts belonging to Pickford and Buddy Rogers, her last husband. Among them are a rare and spectacular beaded gown she wore in the film Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924) designed by Mitchell Leisen, her special Oscar, and a jewelry box.

- The 1980 stage musical The Biograph Girl, about the silent film era, features the character of Pickford.

- In 2007, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences sued the estate of the deceased Buddy Rogers' second wife, Beverly Rogers, in order to stop the public sale of one of Pickford's Oscars.[58]

- A bust and historical plaque marks her birthplace in Toronto, now the site of the Hospital for Sick Children.[59] The plaque was unveiled by her husband Buddy Rogers in 1973. The bust by artist Eino Gira was added ten years later.[60] Her date of birth is stated on the plaque as April 8, 1893. This can only be assumed to be because her date of birth was never registered; throughout her life, beginning as a child, she led many people to believe that she was a year younger than her real age, so that she appeared to be more of an acting prodigy and continued to be cast in younger roles, which were more plentiful in the theatre.[61]

- The family home had been demolished in 1943, and many of the bricks delivered to Pickford in California. Proceeds from the sale of the property were donated by Pickford to build a bungalow in East York, Ontario which was then a Toronto suburb. The bungalow was the first prize in a lottery in Toronto to benefit war charities, and Pickford unveiled the home on May 26, 1943.[62]

- In 1993, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars was dedicated to her.[63]

- Pickford received a posthumous star on Canada's Walk of Fame in Toronto in 1999.

- Pickford was featured on a Canadian postage stamp in 2006.[64]

- From January 2011 until July 2011, the Toronto International Film Festival exhibited a collection of Mary Pickford memorabilia in the Canadian Film Gallery of the TIFF Bell LightBox building.[65]

- In February 2011, the Spadina Museum, dedicated to the 1920s and 1930s era in Toronto, staged performances of Sweetheart: The Mary Pickford Story, a one-woman musical based on the life and career of Pickford.[66]

- Since 2013, the Mary Pickford Foundation has sponsored The Pickford Composers and The Pickford Ensemble at Pepperdine University, composed of students learning to develop music scores for live players to support silent films onscreen.[67]

- In 2013, a copy of an early Pickford film that was thought to be lost (Their First Misunderstanding) was found by Peter Massie, a carpenter tearing down an abandoned barn in New Hampshire. It was donated to Keene State College and is currently undergoing restoration by the Library of Congress for exhibition. The film is notable as being the first in which Pickford was credited by name.[68][69]

- On August 29, 2014, while presenting Behind The Scenes (1914) at Cinecon, film historian Jeffrey Vance announced he is working with the Mary Pickford Foundation on what will be her official biography.

- The Google Doodle of April 8, 2017, commemorated Mary Pickford's 125th birthday.[70]

- The Girls in the Picture, a 2018 novel by Melanie Benjamin, is a historical fiction about the friendship of Mary Pickford and screenwriter Frances Marion.[71]

- On August 20, 2019, the Toronto International Film Festival announced Mati Diop as the recipient of the first Mary Pickford Award.

Pickford's handprints and footprints at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, California

Pickford's handprints and footprints at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, California Pickford's star on the Walk of Fame in Toronto

Pickford's star on the Walk of Fame in Toronto Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study in Hollywood, California

Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study in Hollywood, California

Filmography

References

Citations

- Whitfield, Eileen: Pickford: the Woman Who Made Hollywood (1997), pp. 8, 25, 28, 115, 125, 126, 131, 300, 376. University Press of Kentucky; ISBN 0-8131-2045-4

- Photoplay, Volume 18, Issues 2–6. Macfadden Publications. 1920. p. 99.

- "Mary Pickford, 86, First Great Film Star, Dies Five Days After Massive Stroke". Daily Variety. May 30, 1979. p. 1.

- Whitfield, Eileen: Pickford: the Woman Who Made Hollywood (1997), pp. 8, 25, 28, 115, 125, 126, 131, 300, 376. University Press of Kentucky; ISBN 0-8131-2045-4

- Baldwin, Douglas; Baldwin, Patricia (2000). The 1930s. Weigl. p. 12. ISBN 1-896990-64-9.

- Flom, Eric L. (2009). Silent Film Stars on the Stages of Seattle: A History of Performances by Hollywood Notables. McFarland. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-7864-3908-9.

- Sonneborn, Liz (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts. Infobase. p. 166. ISBN 1-4381-0790-0.

- "Who Was Mary Pickford?". WorldAtlas. July 15, 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Love, Claire; Pollack, Jen; Landsberg, Alison (2017). "Silent Film Actresses and Their Most Popular Characters". National Women's History Museum.

- Kevin Brownlow (1968). The Parade's Gone by ... University of California Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-520-03068-8.

I was baptized Gladys Marie by a French priest – Gladys Marie Smith. David Belasco settled on Pickford after I told him the various names in my family ...

- Leavey, Peggy Dymond (2011). Mary Pickford: Canada's Silent Siren, America's Sweetheart. Dundurn. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4597-0076-5. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

Gladys Smith (Mary Pickford) was baptized in the Catholic faith at the age of four at her home by a visiting priest.

- Leavey, Peggy Dymond (2011). Mary Pickford: Canada's Silent Siren, America's Sweetheart. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55488-945-7. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Eileen Whitfield (2007). Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. p. 38. ISBN 9780813120454.

- Pictorial History of the American Theatre 1860–1985 by Daniel C. Blum, c. 1985

- "Mary Pickford at Filmbug". Filmbug. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Mary Pickford, Sunshine and Shadow, Doubleday & Co., 1955, p. 10.

- Zonarich, Gene (August 3, 2013). "Florence La Badie, Becoming". 11 East 14th Street. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- "Mary Pickford at Golden Silents". Golden Silents.com. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- Charles Affron (2002). Lillian Gish: her legend, her life. University of California Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-520-23434-5.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1999). Mary Pickford Rediscovered. Harry N. Abrams. pp. 86, 93. ISBN 978-0-8109-4374-2.

- "Mary Pickford, filmmaker" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 8, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Lane, Christina (January 29, 2002). Mary Pickford. St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- "Timeline: Mary Pickford". American Experience. PBS. July 23, 2004. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- Balio 1985, p. 159

- Clip of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. describing this incident. Mary Pickford: Muse of the Movies, 2008. Documentary.

- The New York Times, November 10, 1918. p20

- "Timeline: Mary Pickford". American Experience. PBS. July 23, 2004. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- Katz, Ephraim (1998). The Macmillan International Film Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Macmillan. p. 1087. ISBN 0-333-74037-8. OCLC 39216574.

- People & Events: Mary Pickford, Fan Culture, PBS.org; accessed December 4, 2015.

- The Long Decline, PBS.org; accessed December 4, 2015.

- Andre Soares. "Mary Pickford Oscar Controversy". Alt Film Guide.

- "Douglas Fairbanks profile", pbs.org; accessed May 19, 2014.

- Ramon, David (1997). The Dodge Brothers Hour. Clío. ISBN 968-6932-35-6.

- Shipman, David (1995). The Great Movie Stars: The Golden Years. Warner Books. pp. 461–66. ISBN 0-7515-0809-8.

- McDonald, Paul (2000). The Star System: Hollywood's Production of Popular Identities. London: Wallflower. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-903364-02-4.

- "Mary Pickford biography". Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ['https://marypickford.org/mary-pickford-chronology/ "Mary Pickford Chronology"]. Mary Pickford Mary Pickford Foundation. Mary Pickford Foundation. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Corliss, Richard (1998). "queen of the movies". Film Comment. 34 (2): 53–62. ISSN 0015-119X. JSTOR 43455302.

- Peggy Dymond Leavey, Mary Pickford: Canada's Silent Siren, America's Sweetheart. Dundurn Press (2011), pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1554889457

- Kirsty Duncan (2006). Hunting the 1918 Flu: One Scientist's Search for a Killer Virus. University of Toronto Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8020-9456-8. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Peggy Dymond Leavey, Mary Pickford: Canada's Silent Siren, America's Sweetheart. Dundurn Press (2011), p. 110

- Bertensson, Sergei; Fryer, Paul; Shoulgat, Anna (2004). In Hollywood with Nemirovich-Danchenko, 1926–1927: the memoirs of Sergei Bertensson. Scarecrow Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-8108-4988-4. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- "Buddy Rogers, Mary Pickford and Their Children". American Experience. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- Critchlow, Donald T. (2013). When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls, and Big Business Remade American Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9781107650282.

- Critchlow, Donald T. (2013). When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls, and Big Business Remade American Politics. ISBN 978-1107650282.

- "Film Notables Open Drive for G.O.P. President". Los Angeles Times. October 20, 1947. p. 8.

- The 48th Annual Academy Awards. March 29, 1976.

- "Mary Pickford Files TV Bid". Billboard. April 30, 1949. p. 14. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Colombo, John Robert (2011). Fascinating Canada: A Book of Questions and Answers. Dundurn. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55488-923-5.

- "City, fans honor Mary Pickford". The Leader-Post. May 18, 1983. pp. D–8. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- "Mary Pickford Is Dead at 86". The Palm Beach Post. May 30, 1979. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- "Mary Pickford – Hollywood Walk of Fame". October 25, 2019.

- Davis, Laura E. (March 13, 2014). "Throwback Thursday: The story behind stars' handprints in Hollywood". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Endres, Stacey; Cushman, Robert (June 1, 2009). Hollywood at Your Feet: The Story of the World-Famous Chinese Theater. Pomegranate Press. ISBN 9780938817642. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- "TINTIN EN AMÉRIQUE". TINTINOMANIA (in French). October 26, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- "19120 Bubbling Wells Road".

- Iannucci, Lisa (2018). On Location: A Film and TV Lover's Travel Guide. Globe Pequot Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4930-3085-9.

- Siderious, Christina (September 1, 2007). "The Oscar goes to ... Court". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007.; September 1, 2007.

- "Mary Pickford Historical Plaque". Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Filey, Mike (2002). A Toronto Album 2: More Glimpses of the City That Was. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 9781550023930.

- "Archived – Mary Pickford – Celebrating Women's Achievements". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Yardwork at the Mary Pickford Bungalow". April 6, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- "Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Canadians in Hollywood". Canada Post. May 26, 2006. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- "TIFF: Films – Winter Calendar". Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- "America's Sweetheart Home in Toronto". Torontoist. January 27, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- "Up Against the Screen and the Pickford Ensemble". seaver.pepperdine.edu. Pepperdine University. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- "Lost Mary Pickford movie discovered in N.H. barn". CBS News. September 24, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Mary Pickford Film 'Their First Misunderstanding' Found in Barn Is Restored". Huffingtonpost.com. September 24, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- "Mary Pickford's 125th birthday". Google. April 8, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Zimmerman, Jean (January 17, 2018). "'Girls in the Picture' Traces A Friendship in the Flickers". NPR. National Public Radio. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

General sources

- Balio, Tino (1985). The American Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-09873-5. Total pages: 680.

Further reading

- Schmidt, Christel, ed. (2013). Mary Pickford: Queen of the Movies. Library of Congress/University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3647-9.

- Schmidt, Christel (2003). "Preserving Pickford: The Mary Pickford Collection and the Library of Congress". The Moving Image. Association of Moving Image Archivists. 3 (1): 59–81. doi:10.1353/mov.2003.0013. S2CID 191609277.(subscription required)

- Harris, Gloria G.; Hannah S. Cohen (2012). "Chapter 10. Entertainers". Women Trailblazers of California: Pioneers to the Present. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 151–65 [163–66]. ISBN 978-1609496753.

- Petersen, Anne (2014). Scandals of Classic Hollywood. Penguin Publishing.

- Gladys goes to Hollywood at 100 Canadian Heroines: Famous and Forgotten Faces, by Merna Forster, via Google Books, pp. 204 sq.

External links

- Mary Pickford at the Internet Broadway Database

- Mary Pickford at IMDb

- Mary Pickford at the TCM Movie Database

- Mary Pickford at the Women Film Pioneers Project

- About Mary Pickford, from the Mary Pickford Foundation website

- Mary Pickford CBC Radio interview May 25, 1959

- Mary Pickford at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Footage of Mary Pickford with Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks in 1919

- Mary Pickford at Virtual History

- Mary Pickford–Buddy Rogers correspondence, 1943–1976, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Mary Pickford scrapbook, 1915–1917, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Mary Pickford papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- Mary Pickford – Whose Real Name is Gladys Smith from Current Opinion Magazine, June, 1918