Marie Dressler

Marie Dressler (born Leila Marie Koerber; November 9, 1868 – July 28, 1934) was a Canadian stage and screen actress, comedian, and early silent film and Depression-era film star.[3][4]

Marie Dressler | |

|---|---|

Dressler in 1930 | |

| Born | Leila Marie Koerber November 9, 1868 Cobourg, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | July 28, 1934 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale |

| Citizenship |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1886–1934 |

| Spouses | |

After leaving home at the age of 14, Dressler built a career on stage in traveling theatre troupes, where she learned to appreciate her talent in making people laugh. In 1892, she started a career on Broadway that lasted into the 1920s, performing comedic roles that allowed her to improvise to get laughs. She soon transitioned into screen acting and made several shorts, but mostly worked in New York City on stage. During World War I, along with other celebrities, she helped sell Liberty bonds.

In 1914, she played the title role in the first full-length screen comedy, Tillie's Punctured Romance (1914), opposite Charlie Chaplin and Mabel Normand. In 1919, she helped organize the first union for stage chorus players. Her career declined in the 1920s, and Dressler was reduced to living on her savings while sharing an apartment with a friend.

In 1927, she returned to films at the age of 59 and experienced a remarkable string of successes. For her performance in the comedy film Min and Bill (1930), Dressler won the Academy Award for Best Actress. She died of cancer in 1934.

Early life

Dressler was born Leila Marie Koerber on November 9, 1868,[5] in Cobourg, Ontario.[6] She was one of the two daughters of Anna (née Henderson), a musician, and Alexander Rudolph Koerber (1826–1914), a German-born former officer in the Crimean War. Leila's elder sister, Bonita Louise Koerber (1864–1939), later married playwright Richard Ganthony.[7]

Her father was a music teacher in Cobourg and the organist at St. Peter's Anglican Church, where as a child Marie would sing and assist in operating the organ.[8] According to Dressler, the family regularly moved from community to community during her childhood. It has been suggested by Cobourg historian Andrew Hewson that Dressler attended a private school, but this is doubtful if Dressler's recollections of the family's genteel poverty are accurate.[9]

The Koerber family eventually moved to the United States, where Alexander Koerber is known to have worked as a piano teacher in the late 1870s and early 1880s in Bay City and Saginaw (both in Michigan) as well as Findlay, Ohio.[9] Her first known acting appearance, when she was five, was as Cupid in a church theatrical performance in Lindsay, Ontario.[7] Residents of the towns where the Koerbers lived recalled Dressler acting in many amateur productions, and Leila often irritated her parents with those performances.[10]

Stage career

Dressler left home at the age of 14 to begin her acting career with the Nevada Stock Company, telling the company she was actually 18.[11] The pay was either $6 or $8 per week,[7] and Dressler sent half to her mother.[12] At this time, Dressler adopted the name of an aunt as her stage name.[7] According to Dressler, her father objected to her using the name of Koerber. The identity of the aunt was never confirmed, although Dressler denied that she adopted the name from a store awning. Dressler's sister Bonita, five years older, left home at about the same time. Bonita also worked in the opera company.[13] The Nevada Stock Company was a travelling company that played mostly in the American Midwest. Dressler described the troupe as a "wonderful school in many ways. Often a bill was changed on an hour's notice or less. Every member of the cast had to be a quick study".[14] Dressler made her professional debut as a chorus girl named Cigarette in the play Under Two Flags, a dramatization of life in the Foreign Legion.[13]

She remained with the troupe for three years, while her sister left to marry playwright Richard Ganthony. The company eventually ended up in a small Michigan town without money or a booking. Dressler joined the Robert Grau Opera Company, which toured the Midwest, and she received an improvement in pay to $8 per week, although she claimed she never received any wages.[15]

Dressler ended up in Philadelphia, where she joined the Starr Opera Company as a member of the chorus. A highlight with the Starr company was portraying Katisha in The Mikado when the regular actress was unable to go on, due to a sprained ankle, according to Dressler.[16] She was also known to have played the role of Princess Flametta in an 1887 production in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[16] She left the Starr company to return home to her parents in Saginaw. According to her, when the Bennett and Moulton Opera Company came to town, she was chosen from the church choir by the company's manager and asked to join the company. Dressler remained with the company for three years, again on the road, playing roles of light opera.[17]

She later particularly recalled specially the role of Barbara in The Black Hussars, which she especially liked, in which she would hit a baseball into the stands.[18] Dressler remained with the company until 1891, gradually increasing in popularity. She moved to Chicago and was cast in productions of Little Robinson Crusoe and The Tar and the Tartar. After the touring production of The Tar and the Tartar came to a close, she moved to New York City.[19]

In 1892, Dressler made her debut on Broadway at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in Waldemar, the Robber of the Rhine, which only lasted five weeks.[20] She had hoped to become an operatic diva or tragedienne, but the writer of Waldemar, Maurice Barrymore, convinced her to accept that her best success was in comedy roles.[20] Years later, she appeared in motion pictures with his sons, Lionel and John, and became good friends with his daughter, actress Ethel Barrymore. In 1893, she was cast as the Duchess in Princess Nicotine, where she met and befriended Lillian Russell.[21]

Dressler now made $50 per week, with which she supported her parents. She moved on into roles in 1492 Up to Date, Girofle-Girofla, and A Stag Party, or A Hero in Spite of Himself[22] After A Stag Party flopped, she joined the touring Camille D'Arville Company on a tour of the Midwest in Madeleine, or The Magic Kiss, as Mary Doodle, a role giving her a chance to clown.[23]

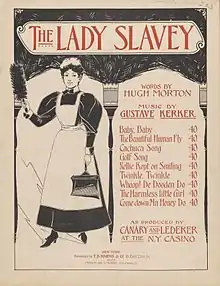

Dressler had her first starring role as household servant Flo Honeydew, a role she performed for four years.

In 1896, Dressler landed her first starring role as Flo in George Lederer's production of The Lady Slavey at the Casino Theatre on Broadway, co-starring British dancer Dan Daly. It was a great success, playing for two years at the Casino. Dressler became known for her hilarious facial expressions, seriocomic reactions, and double takes. With her large, strong body, she could improvise routines in which she would carry Daly, to the delight of the audience.[24]

Dressler's success enabled her to purchase a home for her parents on Long Island.[25] The Lady Slavey success turned sour when she quit the production while it toured in Colorado. The Erlanger syndicate blocked her from appearing on Broadway, and she chose to work with the Rich and Harris touring company.[26] Dressler returned to Broadway in Hotel Topsy Turvy and The Man in the Moon.[27]

She formed her own theatre troupe in 1900, which performed George V. Hobart's Miss Prinnt in cities of the northeastern U.S.[28] The production was a failure, and Dressler was forced to declare bankruptcy.[29]

In 1904, she signed a three-year, $50,000 contract with the Weber and Fields Music Hall management, performing lead roles in Higgledy-Piggledy and Twiddle Twaddle. After her contract expired she performed vaudeville in New York, Boston, and other cities. Dressler was known for her full-figured body, and buxom contemporaries included her friends Lillian Russell, Fay Templeton, May Irwin and Trixie Friganza. Dressler herself was 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall and weighed 200 pounds (91 kg).[30]

In 1907, she met James Henry "Jim" Dalton. The two moved to London, where Dressler performed at the Palace Theatre of Varieties for $1500 per week. After that, she planned to mount a show herself in the West End. In 1909, with members of the Weber organization, she staged a modified production of Higgeldy Piggeldy at the Aldwych Theatre, renaming the production Philopoena after her own role. It was a failure, closing after one week. She lost $40,000 on the production, a debt she eventually repaid in 1930.[31] She and Dalton returned to New York. Dressler declared bankruptcy for a second time.

She returned to the Broadway stage in a show called The Boy and the Girl, but it lasted only a few weeks. She moved on to perform vaudeville at Young's Pier in Atlantic City for the summer. In addition to her stage work, Dressler recorded for Edison Records in 1909 and 1910. In the fall of 1909, she entered rehearsals for a new play, Tillie's Nightmare. The play toured in Albany, Chicago, Kansas City, and Philadelphia, and was a flop. Dressler helped to revise the show, without the authors' permission, and in order to keep the changes she had to threaten to quit before the play opened on Broadway. Her revisions helped make it a big success there. Biographer Betty Lee considers the play the high point of her stage career.[32]

Dressler continued to work in the theater during the 1910s, and toured the United States during World War I, selling Liberty bonds[7] and entertaining the American Expeditionary Forces. American infantrymen in France named both a street and a cow after Dressler. The cow was killed, leading to "Marie Dressler: Killed in Line of Duty" headlines, about which Dressler (paraphrasing Mark Twain) quipped, "I had a hard time convincing people that the report of my death had been greatly exaggerated."[33]

.jpg.webp)

After the war, Dressler returned to vaudeville in New York, and toured in Cleveland and Buffalo. She owned the rights to the play Tillie's Nightmare, the play upon which her 1914 movie Tillie's Punctured Romance was based. Her husband Jim Dalton and she made plans to self-finance a revival of the play. The play fizzled in the summer of 1920, and the production was disbanded. In 1919, during the Actors' Equity strike in New York City, the Chorus Equity Association was formed and voted Dressler its first president.[34]

Dressler accepted a role in Cinderella on Broadway in October 1920, but the play failed after only a few weeks. She signed on for a role in The Passing Show of 1921, but left the cast after only a few weeks. She returned to the vaudeville stage with the Schubert Organization, traveling through the Midwest. Dalton traveled with her, although he was very ill from kidney failure. He stayed in Chicago while she traveled on to St. Louis and Milwaukee. He died while Marie was in St. Louis, and Marie then left the tour. His body was claimed by his ex-wife, and he was buried in the Dalton plot.[35]

After failing to sell a film script, Dressler took an extended trip to Europe in the fall of 1922. On her return she found it difficult to find work, considering America to be "youth-mad" and "flapper-crazy". She busied herself with visits to veteran hospitals. To save money she moved into the Ritz Hotel, arranging for a small room at a discount. In 1923, Dressler received a small part in a revue at the Winter Garden Theatre, titled The Dancing Girl, but was not offered any work after the show closed. In 1925, she was able to perform as part of the cast of a vaudeville show which went on a five-week tour, but still could not find any work back in New York City.[36] The following year, she made a final appearance on Broadway as part of an Old Timers' bill at the Palace Theatre.[37]

Early in 1930, Dressler joined Edward Everett Horton's theater troupe in Los Angeles to play a princess in Ferenc Molnár's The Swan, but after one week, she quit the troupe. Later that year she played the princess-mother of Lillian Gish's character in the 1930 film adaptation of Molnar's play, titled One Romantic Night.[38]

Film career

Dressler had appeared in two shorts as herself, but her first role in a feature film came in 1914 at the age of 44. In 1902, she had met fellow Canadian Mack Sennett and helped him get a job in the theater. After Sennett became the owner of his namesake motion picture studio, he convinced Dressler to star in his 1914 silent film Tillie's Punctured Romance. The film was to be the first full-length, six-reel motion picture comedy. According to Sennett, a prospective budget of $200,000 meant that he needed "a star whose name and face meant something to every possible theatre-goer in the United States and the British Empire."[39]

The movie was based on Dressler's hit Tillie's Nightmare.[40] She claimed to have cast Charlie Chaplin in the movie as her leading man, and was "proud to have had a part in giving him his first big chance."[39] Instead of his recently invented Tramp character, Chaplin played a villainous rogue. Silent film comedian Mabel Normand also starred in the movie. Tillie's Punctured Romance was a hit with audiences, and Dressler appeared in two Tillie sequels and other comedies until 1918, when she returned to vaudeville.[41]

In 1922, after her husband's death, Dressler and writers Helena Dayton and Louise Barrett tried to sell a script to the Hollywood studios, but were turned down. The one studio to hold a meeting with the group rejected the script, saying all the audiences wanted is "young love". The proposed co-star of Lionel Barrymore or George Arliss were rejected as "old fossils".[42] In 1925, Dressler filmed a pair of two-reel short movies in Europe for producer Harry Reichenbach. The movies, titled the Travelaffs, were not released and were considered a failure by both Dressler and Reichenbach. Dressler announced her retirement from show business.[43]

In early 1927, Dressler received a lifeline from director Allan Dwan. Although versions differ as to how Dressler and Dwan met, including that Dressler was contemplating suicide, Dwan offered her a part in a film he was planning to make in Florida. The film, The Joy Girl, an early color production, only provided a small part as her scenes were finished in two days, but Dressler returned to New York upbeat after her experience with the production.[44]

Later that year, Frances Marion, a screenwriter for the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio, came to Dressler's rescue. Marion had seen Dressler in the 1925 vaudeville tour and witnessed Dressler at her professional low-point. Dressler had shown great kindness to Marion during the filming of Tillie Wakes Up in 1917, and in return, Marion used her influence with MGM's production chief Irving Thalberg to return Dressler to the screen.[33] Her first MGM feature was The Callahans and the Murphys (1927), a rowdy silent comedy co-starring Dressler (as Ma Callahan) with another former Mack Sennett comedian, Polly Moran, written by Marion.[33]

The film was initially a success, but the portrayal of Irish characters caused a protest in the Irish World newspaper, protests by the American Irish Vigilance Committee, and pickets outside the film's New York theatre. The film was first cut by MGM in an attempt to appease the Irish community, then eventually pulled from release after Cardinal Dougherty of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia called MGM president Nicholas Schenck.[45] It was not shown again, and the negative and prints may have been destroyed.[45] While the film brought Dressler to Hollywood, it did not re-establish her career. Her next appearance was a minor part in the First National film Breakfast at Sunrise. She appeared again with Moran in Bringing Up Father, another film written by Marion.[46] Dressler returned to MGM in 1928's The Patsy as the mother of the characters played by stars Marion Davies and Jane Winton.[47]

Hollywood was converting from silent films, but "talkies" presented no problems for Dressler, whose rumbling voice could handle both sympathetic scenes and snappy comebacks (the wisecracking stage actress in Chasing Rainbows and the dubious matron in Rudy Vallée's Vagabond Lover). Frances Marion persuaded Thalberg to give Dressler the role of Marthy in the 1930 film Anna Christie. Garbo and the critics were impressed by Dressler's acting ability, and so was MGM, which quickly signed her to a $500-per-week contract. Dressler went on to act in comedic films which were popular with movie-goers and a lucrative investment for MGM. She became Hollywood's number-one box-office attraction, and stayed on top until her death in 1934.[48]

She also took on serious roles. For Min and Bill, with Wallace Beery, she won the 1930–31 Academy Award for Best Actress (the eligibility years were staggered at that time). She was nominated again for Best Actress for her 1932 starring role in Emma, but lost to Helen Hayes. Dressler followed these successes with more hits in 1933, including the comedy Dinner at Eight, in which she played an aging but vivacious former stage actress. Dressler had a memorable bit with Jean Harlow in the film:[49]

Harlow: I was reading a book the other day.

Dressler: Reading a book?

Harlow: Yes, it's all about civilization or something. A nutty kind of a book. Do you know that the guy said that machinery is going to take the place of every profession?Dressler: Oh my dear, that's something you need never worry about.

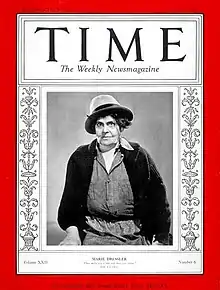

Following the release of Tugboat Annie Dressler appeared on the cover of Time in its issue dated August 7, 1933. Despite glamour actresses such as Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, or Norma Shearer MGM's most prominent female star at the time was Dressler. The aging star consistently packed movie theaters with hits like Min and Bill, Emma, and Tugboat Annie. An exhibitors poll inside the January 1933 issue of Motion Picture Herald had Dressler as the number one box office star in Hollywood.[50]

Coming to movie stardom late, Dressler had no pretensions and a delightful sense of humor. Once, when visiting William Randolph Hearst's California palace San Simeon, a monkey pelted her with some of his excrement. Dressler responded, "Oh, a critic!"[50].

Dressler was very grateful for her career's late resurgence. While working on two films with Wallace Beery, Tugboat Annie and Min and Bill, she refused to take nonsense from the notorious "son of a bitch". In response to one of Beery's insults, she said, "look you silly shit, you pull one more thing like that on me and I'll have your head. On a platter. And not an expensive platter. A little, cheap, lousy, wooden platter. Like John the Baptist. With a personal note to L.B. Mayer."[51]

Dressler's newly regenerated career came to an abrupt end when she was diagnosed with terminal cancer in the early 1930s. MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer learned of Dressler's illness from her doctor (who didn't even tell Dressler of her condition). The studio chief took it upon himself to take charge of Dressler's health. To keep her home, he ordered her not to travel, forcing her to miss a charity event in New York. Although furious, Dressler complied. She only learned about her condition six months later. After some experimental cancer therapy, Dressler returned to work under limitations enforced by Mayer. For the rest of her career, the actress only worked three hours a day and had mandatory stand-ins wherever possible. Before she died in July 1934, Dressler starred in two more features and had a small part in Dinner at Eight.[50]

She appeared in more than 40 films, and achieved her greatest successes in talking pictures made during the last years of her life. The first of her two autobiographies, The Life Story of an Ugly Duckling, was published in 1924. A second book, My Own Story, "as told to Mildred Harrington", appeared a few months after her death.

Personal life

Dressler's first marriage was to an American, George Francis Hoeppert (1862 – September 7, 1929), a theatrical manager. His surname is sometimes given as Hopper. The couple married on May 6, 1894, in Grace Church Rectory, Greenville, New Jersey, as biographer Matthew Kennedy wrote, under her birth name, Leila Marie Koerber.[52] Some sources indicate Dressler had a daughter who died as a small child, but this has not been confirmed.

Her marriage to Hoeppert gave Dressler U.S. citizenship, which was useful later in life, when immigration rules meant permits were needed to work in the United States, and Dressler had to appear before an immigration hearing.[1] Ever since her start in the theatre, Dressler had sent a portion of her salary to her parents. Her success on Broadway meant she could afford to buy a home and later a farm on Long Island, which she shared with her parents. Dressler made several attempts to set up theatre companies or theatre productions of her own using her Broadway proceeds, but these failed and she had to declare bankruptcy several times.[53]

In 1907, Dressler met a Maine businessman, James Henry "Jim" Dalton, who became her companion until his death [Death Record 3104-27934] on November 29, 1921, at the Congress Hotel in Chicago from diabetes. According to Dalton, the two were married in Europe in 1908.[54] However, according to Dressler's U.S. passport application, the couple married in May 1904 in Italy.[55]>

Dressler reportedly later learned that the "minister" who had married them in Monte Carlo was actually a local man paid by Dalton to stage a fake wedding.[56] Dalton's first wife, Lizzie Augusta Britt Dalton, claimed he had not consented to a divorce or been served divorce papers, although Dalton claimed to have divorced her in 1905.[57] By 1921, Dalton had become an invalid due to diabetes mellitus, and watched her from the wings in his wheelchair. After his death that year, Dressler was planning for Dalton to be buried as her husband, but Lizzie Dalton had Dalton's body returned to be buried in the Dalton family plot.[58]

After Dalton's death, which coincided with a decline in her stage career, Dressler moved into a servant's room in the Ritz Hotel to save money.[59] Eventually, she moved in with friend Nella Webb to save on expenses.[44] After finding work in film again in 1927, she rented a home in Hollywood on Hillside Avenue. Although Dressler was working from 1927 on, she was still reportedly living hand to mouth. In November 1928, wealthy friends Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Neurmberg gave her $10,000, explaining they planned to give her a legacy someday, but they thought she needed the money immediately.[60] In 1929, she moved to Los Angeles to 6718 Milner Road in Whitley Heights, then to 623 North Bedford Drive in Beverly Hills, both rentals. She moved to her final home at 801 North Alpine in Beverly Hills in 1932, a home which she bought from the estate of King C. Gillette.[61] During her seven years in Hollywood, Dressler lived with her maid Mamie Cox and later Mamie's husband Jerry.[61]

Miscellanea

Although atypical in size for a Hollywood star, Dressler was reported in 1931 to use the services of a "body sculptor to the stars", Sylvia of Hollywood, to keep herself at a steady weight.[62]

Biographers Betty Lee and Matthew Kennedy document Dressler's long-standing friendship with actress Claire Du Brey, whom she met in 1928.[63] Dressler and Du Brey's falling out in 1931 was followed by a later lawsuit by Du Brey, who had been trained as a nurse, claiming back wages as the elder woman's nurse.[64]

Death

On Saturday, July 28, 1934, Dressler died of cancer, aged 65, in Santa Barbara, California. After a private funeral held at The Wee Kirk o' the Heather chapel, she was interred in a crypt in the Great Mausoleum in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.[65]

Dressler left an estate worth $310,000, the bulk left to her sister Bonita.[66] She bestowed her 1933 Duesenberg Model J automobile and $35,000 to her maid of 20 years, Mamie Steele Cox, and $15,000 to Cox's husband, Jerry R. Cox, who had served as Dressler's butler for four years.[67] Dressler intended that the funds should be used to provide a place of comfort for black travelers,[68] and the Coxes used the funds to open the Coconut Grove night club and adjacent tourist cabins in Savannah, Georgia, in 1936, named after the night club in Los Angeles.[67]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

Dressler's birth home in Cobourg, Ontario, is known as Marie Dressler House and is open to the public. The home was converted to a restaurant in 1937 and operated as a restaurant until 1989, when it was damaged by fire. It was restored, but did not open again as a restaurant. It was the office of the Cobourg Chamber of Commerce until its conversion to its current use as a museum about Dressler and as a visitor information office for Cobourg.[69] Each year, the Marie Dressler Foundation Vintage Film Festival is held, with screenings in Cobourg and in Port Hope, Ontario.[70] A play about the life of Marie Dressler called "Queen Marie" was written by Shirley Barrie and produced at 4th Line Theatre in 2012 and Alumnae Theatre in 2018.[71]

For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Dressler has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1731 Vine Street, added in 1960.[72] After Min and Bill, Dressler and Beery added their footprints to the cement forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, with the inscription "America's New Sweethearts, Min and Bill."[73]

Canada Post, as part of its "Canada in Hollywood" series, issued a postage stamp on June 30, 2008, to honour Marie Dressler.[74]

Dressler is beloved in Seattle. She played in two films based on historical Seattle characters. Tugboat Annie (1933) was loosely based on Thea Foss, of Seattle. Likewise Hattie Burns, in Politics (1931), was based on Bertha Knight Landes, the first woman to become mayor of Seattle.

Dressler's 152nd birthday was commemorated in a Google Doodle on November 9, 2020.[75]

Stage

Note: The list below is limited to New York/Broadway theatrical productions

| Date | Title | Role | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 18, 1897 – November 6, 1897 | Courted Into Court | Dottie Dimple | [76][77][78] | |

| April 24, 1899 – November 4, 1899 | The Man in the Moon | Viola Alum | [76][79] | |

| December 25, 1900 – November 19, 1901 | Miss Prinnt | Helen Prinnt | [76][80] | |

| May 13, 1901 – June 6, 1901 | The King's Carnival | Anne | [76][81] | |

| September 9, 1901 – October 12, 1901 | The King's Carnival | Anne | [76][81] | |

| February 5, 1902 – June 4, 1902 | The Hall of Fame | Lady Oblivion | [76][82] | |

| September 6, 1902 – October 4, 1902 | King Highball | Ex-Queen Tarantula | [76][83] | |

| October 20, 1904 – March 25, 1905 | Higgledy-Piggledy | Philopena Schnitz | [76][84] | |

| January 5, 1905 – Closing date unknown | The College Widower | Tilly Buttin | [76][85] | |

| August 26, 1905 – September 9, 1905 | Higgledy-Piggledy | Philopena Schnitz | [76][84] | |

| January 1, 1906 – June 2, 1906 | Twiddle-Twaddle | Matilda Grabfelder | [76][86] | |

| May 31, 1909 – June 19, 1909 | The Boy and the Girl | Gladys De Vine | [76][87] | |

| May 5, 1910 – Dec 1911 | Tillie's Nightmare | Tillie Blobbs | [76][88] | |

| November 21, 1912 – January 11, 1913 | Roly Poly | Bijou Fitzsimmons | [76][89] | |

| November 21, 1912 – January 11, 1913 | Without the Law | Merry Urner | [76][90] | |

| March 10, 1913 – March 15, 1913 | Marie Dressler's "All Star Gambol" | Self | Dressler wrote it, staged it, and did the scenic and costume designs | [76][91] |

| December 28, 1914 – Mar 1915 | A Mix-up | Self | Also directed | [76][92] |

| November 6, 1916 – April 28, 1917 | The Century Girl | [76][93] | ||

| December 29, 1920 – May 28, 1921 | The Passing Show of 1921 | Frances Belasco Starr Mrs. Hopwood |

[76][94] | |

| January 24, 1923 – May 12, 1923 | The Dancing Girl | Multiple roles | [76][95] | |

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes Studio/Distributor |

Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1909 | Marie Dressler | Herself | Short subject Edison Mfg. Cp. |

[96] |

| 1910 | Actors' Fund Field Day | Herself | Silent documentary Vitagraph Studios |

[97] |

| 1914 | Tillie's Punctured Romance | Tillie Banks, Country Girl | Keystone Studios | [98] |

| 1915 | Tillie's Tomato Surprise | Tillie Banks | Lubin Manufacturing Company | [98] |

| 1917 | Fired | Writer and director Marie Dressier Motion Picture Company Goldwyn Pictures |

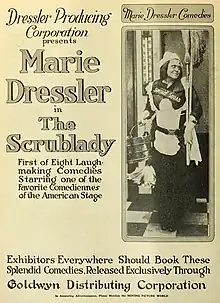

[98] | |

| 1917 | The Scrub Lady | Tillie | Writer and director Marie Dressier Motion Picture Company Goldwyn Pictures |

[98] |

| 1917 | Tillie Wakes Up | Tillie Tinkelpaw | World Film Company | [98] |

| 1918 | The Cross Red Nurse sometimes called The Red Cross Nurse {{{last}}} | Writer and director Marie Dressier Motion Picture Company Goldwyn Pictures |

[98] | |

| 1918 | The Agonies of Agnes | Writer and director Marie Dressier Motion Picture Company Goldwyn Pictures |

[98] | |

| 1927 | The Joy Girl | Mrs. Heath | Fox Film | [99] |

| 1927 | The Callahans and the Murphys | Mrs. Callahan | MGM | [99] |

| 1927 | Breakfast at Sunrise | Queen | Constance Talmadge | [99] |

| 1928 | The Patsy | Ma Harrington | MGM | [99] |

| 1928 | Bringing Up Father | Annie Moore | MGM | [99] |

| 1929 | Voice of Hollywood No. 1 | Herself | Uncredited | [100] |

| 1929 | The Vagabond Lover | Mrs. Ethel Bertha Whitehall | RKO Pictures | [101] |

| 1929 | Dangerous Females | Sarah Bascom | Paramount Pictures | [101] |

| 1929 | Hollywood Revue of 1929 | Herself | MGM | [101] |

| 1929 | The Divine Lady | Mrs. Hart | First National Pictures | [99] |

| 1930 | The Voice of Hollywood No. 14 | Herself | Uncredited | [100] |

| 1930 | Screen Snapshots Series 9, No. 14 | Herself, at Premiere | [102] | |

| 1930 | The March of Time | Herself, "Old Timer" sequence | Unfinished film, never released | [103] |

| 1930 | Anna Christie | Marthy Owens | MGM | [101] |

| 1930 | Derelict | [104] | ||

| 1930 | Let Us Be Gay | Mrs. 'Bouccy' Bouccicault | MGM | [105] |

| 1930 | Caught Short | Marie Jones | MGM | [105] |

| 1930 | One Romantic Night | Princess Beatrice | United Pictures Corporation | [105] |

| 1930 | The Girl Said No | Hettie Brown | MGM | [101] |

| 1930 | Chasing Rainbows | Bonnie | MGM | [101] |

| 1930 | Min and Bill | Min Divot, Innkeeper | Won- Academy Award for Best Actress MGM |

[105] |

| 1931 | Jackie Cooper's Birthday Party | Herself | ||

| 1931 | Politics | Hattie Burns | MGM | [105] |

| 1931 | Reducing | Marie Truffle | MGM | [105] |

| 1932 | Prosperity | Maggie Warren | MGM | [106] |

| 1932 | Emma | Emma Thatcher Smith | Nominated—Academy Award for Best Actress MGM |

[107] |

| 1933 | Going Hollywood | Herself, Premiere Clip | MGM | [108] |

| 1933 | Dinner at Eight | Carlotta Vance | MGM | [106] |

| 1933 | Tugboat Annie | Annie Brennan | MGM | [106] |

| 1933 | Broadway to Hollywood | MGM | [109] | |

| 1933 | Christopher Bean | Abby | final film before her death MGM |

[106] |

| 1976 | That's Entertainment, Part II | MGM |

[110] | |

| 1979 | Ken Murray Shooting Stars | Ken Murray Productions | [111] |

Quotes

See also

Bibliography

- Bradley, Edwin M. (2009). The First Hollywood Sound Shorts, 1926–1931. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4319-2.

- Bradley, Edwin M. (2004). The First Hollywood Musicals: A Critical Filmography of 171 Features, 1927 through 1932. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2029-2.

- Kennedy, Matthew (1999). Marie Dressler: A Biography, With a Listing of Major Stage Performances, a Filmography And a Discography. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0520-1.

- Silverman, Steven M. (1999). Funny Ladies. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3337-3.

- IBDB for Marie Dressler

- Lee, Betty (1997). Marie Dressler: The Unlikeliest Star. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-4571-6.(subscription required)

- Rapf, Joanna E. (2010). "Marie Dressler Thief of the Talkies". Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 250, 250–268, 257, 261, 264. ISBN 978-0-8135-4929-3.(subscription required)

- Sturtevant, Victoria (October 2010). A Great Big Girl Like Me: The Films of Marie Dressler. Urbana, Il.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09262-6.(subscription required)

- Wagner, Kristen Anderson (March 5, 2018). Comic Venus: Women and Comedy in American Silent Film. Detroit. MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-4103-2.(subscription required)

Notes

- "Actress Saw Two Marriages Fail in 14 years". Calgary Daily Herald. August 11, 1934. p. 5. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- Dressler and Dalton married in 1904 according to Dressler's U.S. passport application (1924), ancestry.com; accessed July 27, 2016.

- Obituary Variety, July 31, 1934, page 54.

- Marie Dressler: North American Theatre Online, alexanderstreet.com; accessed July 27, 2016.

- Kennedy 1999, p. 9.

- Britanica, Encyclopedia (2019). "Marie Dressler | Canadian actress". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- "Famous Star Is Dead at 62". Montreal Gazette. July 30, 1934. pp. 1, 9. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- "Cobourg Mourning Marie Dressler". Montreal Gazette. July 31, 1934. p. 5. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- Lee 1997, p. 9.

- Lee 1997, p. 10.

- Lee 1997, pp. 11–12.

- Lee 1997, p. 14.

- Lee 1997, p. 13.

- Lee 1997, pp. 15–16.

- Lee 1997, p. 17.

- Lee 1997, p. 18.

- Lee 1997, p. 20.

- Lee 1997, pp. 20–21.

- Lee 1997, pp. 21–22.

- Lee 1997, p. 24.

- Lee 1997, pp. 24–25.

- Lee 1997, pp. 26–28.

- Lee 1997, p. 28.

- Lee 1997, p. 29.

- Lee 1997, pp. 30–31.

- Lee 1997, pp. 31–32.

- Lee 1997, pp. 33–, 37.

- ""MISS PRINNT" AT ALBANY; Marie Dressler Scores a Success in G.V. Hobart's New Play". The New York Times. November 5, 1900. p. 5.

- Lee 1997, p. 39.

- Kennedy 1999, p. 2.

- Lee 1997, p. 69.

- Lee 1997, p. 78.

- Silverman 1999, p. 23.

- "History". actorsequity.org. Equity Timeline. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Lee 1997, p. 145.

- Lee 1997, pp. 153–54.

- Lee 1997, p. 156.

- Lee 1997, p. 173.

- Lee 1997, p. 103.

- Lee 1997, p. 105.

- Kennedy, Matthew (2009). "Marie Dressler". coburghistory.ca. CDCI West History Department. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Lee 1997, p. 150.

- Lee 1997, p. 155.

- Lee 1997, p. 159.

- Lee 1997, p. 165.

- Lee 1997, p. 166.

- Lee 1997, p. 167.

- "Top Box Office Stars of 1933". amiannoying.com. Am I Annoying. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- Silverman 1999, p. 24.

- Eyman, S. Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer. Simon and Schuster (2005). ISBN 0-7432-0481-6 pg 191.

- Eyman, S. Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer. Simon and Schuster (2005). ISBN 0-7432-0481-6 pg 223.

- Ancestry.ca file 45594_2321306652_0102-00155.jpg

- Lee 1997, p. 70.

- Lee 1997, p. 64.

- U.S. passport application

- Lee 1997, p. 65.

- Lee 1997, p. 102.

- Lee 1997, p. 148.

- Lee 1997, p. 152.

- Lee 1997, p. 168.

- Lee 1997, p. 169.

- Coons, R. (September 2, 1931). "Marathons Common To Movies". The Olean Herald.

- Kennedy 1999, pp. 143–144.

- Soares, Andre (December 11, 2014). "Marie Dressler:Q&A with Biographer Matthew Kennedy-part 3". mariedressler.ca. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Marie Dressler Loses Long Battle For Life". The Portsmouth Times. July 29, 1934. p. 1. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- "Marie Dressler's Will Is Probated". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. August 15, 1934. p. 3. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- "Marie Dressler's Old Servants Open Night Club for Negros With Money Actress Left Them". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. April 10, 1936. p. 5A. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- "Southward", Chas. A. R. McDowell, The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1940 edition.

- "Marie Dressler House". Vintage Film Festival. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "About the Marie Dressler Foundation". Marie Dressler Foundation. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- "Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia – Barrie, Shirley". www.canadiantheatre.com.

- "Marie Dressler: Hollywood Walk of Fame". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- Lee 1997, p. 182.

- "Westmount schoolgirl went on to win an Oscar". canada.com. April 7, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- "Marie Dressler's 152nd Birthday". Google. November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "Marie Dressler – Broadway Cast & Staff | IBDB". www.ibdb.com. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Week's Plays – Courted Into Court". The Buffalo Commercial. November 30, 1897.

- Lee 1997, pp. 32–33.

- Lee 1997, pp. 37–38.

- Lee 1997, pp. 38–39.

- Lee 1997, pp. 39–40.

- Lee 1997, p. 42.

- Lee 1997, pp. 42, 45.

- Lee 1997, pp. 50–53.

- Lee 1997, pp. 52–53.

- Lee 1997, pp. 54–55, 58.

- Lee 1997, pp. 70–72.

- Lee 1997, pp. 74–79, 81–83, 94, 105–6, 110, 113, 135, 143–45.

- Lee 1997, pp. 87–91.

- Lee 1997, p. 88.

- Lee 1997, pp. 92–93, 93, 94–95, 95.

- Lee 1997, pp. 111–14, 116, 117.

- Lee 1997, p. 122.

- Lee 1997, p. 147.

- Lee 1997, p. 153.

- "Marie Dressler". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Actors Field Fund Day". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Lee 1997, p. 270.

- Lee 1997, p. 271.

- Bradley 2009, p. 330.

- Lee 1997, p. 272.

- "Screen Snapshots". The Columbia Shorts Department. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Bradley 2004, p. 261.

- "Marie Dressler's Films". Marie Dressler Foundation. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- Lee 1997, p. 273.

- Lee 1997, p. 274.

- Lee 1997, pp. 273–274.

- "Going Hollywood". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Broadway to Hollywood". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "That's Entertainment, Part II". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Ken Murray Shooting Stars". AFI|Catalog. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Biography for Marie Dressler". IMDB. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

External links

- Interview in Vanity Fair, October 11, 1902

- Marie Dressler at Women Film Pioneers Project

- Marie Dressler at the Internet Broadway Database

- Cylinder recordings at Cylinder Audio Archive, University of California Library

Images

- 1922 passport photo

- Ephemera at Virtual History

- Marie Dressler sneezing, c.1900

- Ephemera at New York Public Library

- 1908 portrait at Washington University Libraries (archived)

- 1911 still from Tillie's Nightmare at Washington University Libraries (archived)

- 1917 still from Tillie the Scrub Lady at Washington University Libraries (archived)