Rockwood, Tennessee

Rockwood is a city in Roane County, Tennessee, United States. Its population was 5,562 at the time of the 2010 census. It is included in the Harriman, Tennessee Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Rockwood, Tennessee | |

|---|---|

| City of Rockwood | |

Rockwood Street | |

| Motto: "The place to be in Tennessee" | |

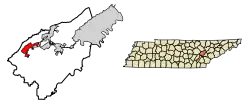

Location of Rockwood in Roane County, Tennessee. | |

| Coordinates: 35°52′9″N 84°40′31″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| County | Roane |

| Founded | 1868 |

| Incorporated | 1890[1] |

| Named for | William O. Rockwood |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jason Jolly |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.04 sq mi (20.83 km2) |

| • Land | 8.02 sq mi (20.76 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 892 ft (272 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 5,444 |

| • Density | 679.23/sq mi (262.25/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 37854 |

| Area code | 865 |

| FIPS code | 47-64440[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1299838[3] |

| Website | City website |

Geography

Rockwood is located at 35°52′9″N 84°40′31″W (35.869147, -84.675176).[6] The city is situated at the base of the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau, known locally as Walden Ridge. The boundary between the Eastern Time Zone and Central Time Zone runs along Rockwood's western boundary. The Watts Bar Lake impoundment of the Tennessee River provides much of Rockwood's southern boundary.

Rockwood is situated around a series of roads which intersect U.S. Route 70 between its junction with State Route 29 in the northeast and State Route 27 to the southwest. In recent years, the town has expanded toward Interstate 40 to the northeast. Rockwood is a familiar site to travelers who frequent I-40 between Knoxville and Nashville, as dramatic views of Rockwood and the Tennessee Valley beyond line the interstate just before it peaks at the edge of the Cumberland Plateau.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.9 square miles (20 km2), of which 7.9 square miles (20 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (0.63%) is water.

Climate

| Climate data for Rockwood, Tennessee (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1962–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

77 (25) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 64.9 (18.3) |

69.3 (20.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

85.0 (29.4) |

87.1 (30.6) |

92.0 (33.3) |

95.0 (35.0) |

93.4 (34.1) |

90.5 (32.5) |

82.1 (27.8) |

75.0 (23.9) |

65.6 (18.7) |

95.7 (35.4) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 46.7 (8.2) |

51.2 (10.7) |

60.6 (15.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

84.5 (29.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

86.5 (30.3) |

81.8 (27.7) |

70.7 (21.5) |

58.9 (14.9) |

49.8 (9.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.2 (2.9) |

40.4 (4.7) |

48.5 (9.2) |

56.9 (13.8) |

65.4 (18.6) |

73.3 (22.9) |

76.8 (24.9) |

75.7 (24.3) |

70.1 (21.2) |

58.4 (14.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

40.1 (4.5) |

57.5 (14.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27.7 (−2.4) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

36.3 (2.4) |

43.5 (6.4) |

53.1 (11.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

66.2 (19.0) |

64.9 (18.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

46.1 (7.8) |

35.3 (1.8) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

46.1 (7.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 8.2 (−13.2) |

13.0 (−10.6) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

38.8 (3.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

57.2 (14.0) |

56.4 (13.6) |

43.5 (6.4) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

13.8 (−10.1) |

4.6 (−15.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−10 (−23) |

1 (−17) |

21 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

44 (7) |

28 (−2) |

21 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−8 (−22) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.41 (137) |

5.43 (138) |

5.46 (139) |

5.63 (143) |

4.73 (120) |

5.46 (139) |

5.96 (151) |

3.82 (97) |

4.45 (113) |

3.48 (88) |

4.62 (117) |

6.01 (153) |

60.46 (1,536) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.7 (1.8) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.0 (5.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 9.4 | 10.5 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 10.1 | 113.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[7][8] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,011 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,305 | 128.0% | |

| 1900 | 2,899 | 25.8% | |

| 1910 | 3,660 | 26.3% | |

| 1920 | 4,652 | 27.1% | |

| 1930 | 3,808 | −18.1% | |

| 1940 | 3,981 | 4.5% | |

| 1950 | 4,272 | 7.3% | |

| 1960 | 5,345 | 25.1% | |

| 1970 | 5,259 | −1.6% | |

| 1980 | 5,687 | 8.1% | |

| 1990 | 5,348 | −6.0% | |

| 2000 | 5,774 | 8.0% | |

| 2010 | 5,562 | −3.7% | |

| 2020 | 5,444 | −2.1% | |

| Sources:[9][10][4] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 4,710 | 86.52% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 227 | 4.17% |

| Native American | 22 | 0.4% |

| Asian | 37 | 0.68% |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 315 | 5.79% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 132 | 2.42% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 5,444 people, 2,129 households, and 1,175 families residing in the city.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 5,774 people, 2,478 households, and 1,558 families residing in the city. The population density was 731.4 inhabitants per square mile (282.4/km2). There were 2,729 housing units at an average density of 345.7 per square mile (133.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.86% White, 5.44% African American, 0.26% Native American, 0.29% Asian, 0.21% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. Hispanic/Latino/Tejano of any race were 0.81% of the population.

There were 2,478 households, out of which 25.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.8% were married couples living together, 14.7% had a female households with no husband present, and 37.1% were non-families. 34.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.87.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.5% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 25.0% from 45 to 64, and 20.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,986, and the median income for a family was $32,237. Males had a median income of $27,188 versus $20,755 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,106. About 17.4% of families and 21.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.4% of those under age 18 and 17.6% of those age 65 or over.

History

Early history

A Cherokee village situated in what is now Rockwood was the headquarters of Chief Tallentuskie, a Cherokee leader in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[12]

Roane Iron Company

Union general John T. Wilder, who in the 1850s had managed a foundry in Indiana, noted the iron ore and coal deposits of the Cumberland Plateau region while operating in the area during the Civil War. After the war, Wilder and Ohio-born Knoxville Iron Company founder Hiram Chamberlain (1835–1916) purchased 900 acres (360 ha) at what is now Rockwood, selecting the location due to the ore and coal resources at the base of Walden Ridge, the proximity to the Tennessee River, and an assumption that the encroaching railroads would descend the Plateau at nearby Emory Gap. Wilder and Chamberlain enlisted several other investors from Indiana and Ohio, and the Roane Iron Company was chartered on June 18, 1867.[1] By late 1868, the company had constructed a blast furnace with a capacity of 15 tons per day between the ridge and the end of what is now Rockwood Street.[13]

The company mined coal and iron ore along the ridge, which it transported by narrow-gauge rail to the furnace site. The coal was delivered to coking ovens, where it was converted into coke, and the coke was then used to generate the temperatures needed to convert the iron ore into pig iron. The pig iron was then shipped by river to rolling mills in Knoxville and Chattanooga, and was used primarily in railroad construction. In the early 1880s, Roane Iron purchased a rolling mill in Chattanooga and experimented with steel production, but the Walden Ridge ore proved to be too low-quality for such a process, and the company abandoned its steel venture in 1889.[14]

Roane Iron's Rockwood furnace employed a mix of local labor (both caucasian and African-American) and immigrants (especially Welsh immigrants), and did not practice wage discrimination.[1] The company paid workers either cash, which was issued on paydays, or scrip, which could be issued anytime at the worker's request. Other than a miners' strike in 1904, Roane Iron experienced relatively few labor disputes, even though labor organizations were active in Rockwood. A series of mining accidents— namely a 1926 mine explosion— damaged the company's image and led to out-of-control workers' compensation payments, however, and in 1929 Roane Iron shut down operations.[1]

Development of Rockwood

Worried that the region's Confederate-sympathizers might shun an operation led by a well-known Union general, Wilder decided to name Roane Iron's company town after one of its lesser-known Indiana investors, William O. Rockwood. In spite of the name, William Rockwood played only a minor role in Roane Iron's affairs, and the early development of the town was largely the work of Wilder and Chamberlain. Unlike the "boom" towns in nearby Cardiff and Harriman, Rockwood's growth was gradual. Rockwood's population grew from 696 in 1870 to 1,011 in 1880. By 1890, the city's population had swelled to 2,305.[1]

For the first 50 years of its existence, Rockwood was polarized by the temperance issue. Wilder, a prohibitionist, banned alcoholic beverages on company property, and tried in vain to prevent drunkenness in the town throughout the 1870s. Saloons became commonplace in Rockwood in the 1880s, however, and Roane Iron began to struggle with absenteeism, as many employees worked for just a few days per week in order to make enough money for a "weekend of drinking and fighting."[1] In 1887, after the state's "four-mile" law effectively banned saloons in unincorporated areas, a section of the town incorporated as "East Rockwood" to dodge the law. Rockwood, which incorporated in 1890, passed an ordinance banning the sale of alcohol in 1903, but the ordinance didn't apply to railroads, and the so-called "jug train" from Chattanooga continued supplying Rockwood with liquor until the statewide prohibition law took effect in 1909.[1]

Noting the success of land auctions in nearby Cardiff and Harriman, Roane Iron held its own land auction for Rockwood in May 1890, selling several hundred lots and raising $600,000. To promote the city, the company laid out new streets, built new hotels, and allowed general stores to set up shop in the city and compete with the company store.[1] These de-paternalization measures helped Rockwood survive the Panic of 1893, which doomed neighboring Cardiff.[1]

20th century

In the early 20th century, Rockwood's economy further diversified. Former Roane Iron employee James Tarwater founded Rockwood Mills, which manufactured hosiery, in 1905. Another former Roane Iron employee, Sewell Howard, established Rockwood Stove Works in 1916.

On 4 October 1926, twenty-eight people were killed in a mine explosion in the area.[15]

After Roane Iron's collapse in 1929, Rockwood struggled with unemployment. At the outbreak of World War II, however, the Tennessee Products Corporation reopened the iron works to produce ferromanganese for the wartime effort.[1] Like other Roane County communities, Rockwood's economy was boosted by the government's construction of nearby Oak Ridge during World War II.

Notable people

- Harry T. Burn (1895–1977), Tennessee legislator who broke the deadlock on the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution and gave women the right to vote in the United States, worked as the president of the First National Bank of Rockwood from 1951 to 1965.[16]

- Christian H. Cooper (b. 1976), derivatives trader, Truman National Security Fellow and member of the Council on Foreign Relations

- Nancy-Ann DeParle (b. 1956), Rhodes Scholar, American expert on health care issues and director of White House Office of Health Reform.

- Michael Calvin McGee (1943-2002), academic

- C. M. Newton (1930-2018), basketball player, coach and administrator, member of the Basketball Hall of Fame

References

- William Moore, "Preoccupied Paternalism: The Roane Iron Company In Her Company Town— Rockwood, Tennessee." East Tennessee Historical Society Publications Vol. 39 (1967), pp. 56-70.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Rockwood, Tennessee

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- "Station: Rockwood 2, TN". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- Stanley Wassom, "Rockwood — A Historic Perspective". The City of Rockwood official website, 2006. Retrieved: 29 December 2007.

- John Benhart, Appalachian Aspirations: The Geography of Urbanization and Development in the Upper Tennessee River Valley, 1865-1900 (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2007), pp. 5-7.

- Benhart, pp. 34-41.

- ""Disasters"". Powell Valley News. January 7, 1927. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- Boyd, Tyler L. (2019). Tennessee Statesman Harry T. Burn: Woman Suffrage, Free Elections, and a Life of Service. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-4671-4318-9. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

External links

- Official City of Rockwood website

- Municipal Technical Advisory Service entry for Rockwood — information on local government, elections, and link to charter

- Rockwood, Tennessee — Roane County Heritage Commission website