Roger de Pont L'Évêque

Roger de Pont L'Évêque (or Robert of Bishop's Bridge; c. 1115–1181) was Archbishop of York from 1154 to 1181. Born in Normandy, he preceded Thomas Becket as Archdeacon of Canterbury, and together with Becket served Theobald of Bec while Theobald was Archbishop of Canterbury. While in Theobald's service, Roger was alleged to have committed a crime which Becket helped to cover up. Roger succeeded William FitzHerbert as archbishop in 1154, and while at York rebuilt York Minster, which had been damaged by fire.

Roger de Pont L'Évêque | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of York | |

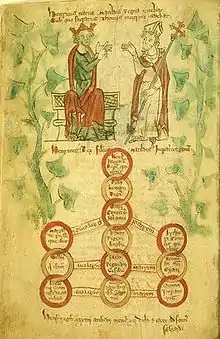

Sketch of Roger from the Becket Leaves (c. 1220-1240), possibly by Matthew Paris | |

| Appointed | before October 1154 |

| Term ended | 26 November 1181 |

| Predecessor | William of York |

| Successor | Geoffrey Plantagenet |

| Other post(s) | Archdeacon of Canterbury |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 10 October 1154 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1115 |

| Died | 26 November 1181 Yorkshire |

| Buried | Durham Cathedral |

Roger did not become deeply involved in the dispute between King Henry II of England and Becket until 1170, when the King had Roger preside at the coronation of the king's son Henry the Young King, a function that would normally have been performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. In retaliation Becket excommunicated Roger in late 1170, and some have seen this excommunication as one reason for King Henry's anger at Becket which led to Becket's murder. After being suspended from office by the pope for his supposed role in Becket's death, Roger was eventually restored to office in late 1171, and died in 1181. The see of York remained vacant after his death until 1189.

Early life

Roger was probably born around 1115 and was a native of Pont-l'Évêque in Normandy. His only known relative was a nephew, Geoffrey, to whom Roger gave the offices of provost of Beverley Minster and archdeacon of York.[1] Roger was a clerk of Archbishop Theobald's before being named Archdeacon of Canterbury, some time after March 1148.[2] When Becket joined Theobald's household, their contemporary William fitzStephen recorded that Roger disliked the new clerk, and twice drove Thomas away before the archbishop's brother Walter arranged Thomas' return.[3]

According to John of Salisbury, who first reported this story in 1172 after the death of Thomas Becket, as a young clerk Roger was involved in a scandal involving a homosexual relationship with a boy named Walter. After Walter made the relationship public, Roger reacted by embroiling Walter in judicial case that ended with Walter's eyes being gouged out. When Walter then accused Roger of this crime, Roger persuaded a judge to condemn Walter to death by hanging. Becket supposedly was involved in the cover-up afterwards, by arranging with Hilary of Chichester and John of Coutances for Roger to swear an oath that he was innocent. According to John of Salisbury, Roger then went to Rome in 1152 and was cleared of involvement by Pope Eugene III. John of Salisbury further alleges that it was only after bribery that the pope cleared Roger. Frank Barlow, a medieval historian and Becket's biographer, points out in his biography of Becket that while Roger was accused of these crimes, and may even have been guilty of some sort of criminal homosexuality, John of Salisbury's motives for bringing up this story in 1172 were almost certainly to defame Roger. Such a story would naturally have put Roger in the worst possible light.[3]

It was while Roger was Theobald's clerk that he made lasting friendships with Gilbert Foliot and Hugh de Puiset.[1] Roger attended the Council of Reims in 1148 with Theobald, John of Salisbury, and possibly Thomas Becket. This council condemned some of Gilbert de la Porrée's teachings, and consecrated Foliot as Bishop of Hereford.[4] While it was later recalled that Roger and Becket did not get along, there is no evidence of hatred between the two before the Becket crisis happened.[3]

Archbishop

Roger was consecrated Archbishop of York on 10 October 1154.[5] When he went north to York, the legal scholar Vacarius, who had been part of Theobald's household, followed Roger and spent the next 50 years in the north.[6] Vacarius was responsible for introducing Roman civil law into England, and did so under the patronage of Roger. He wrote a standard textbook on the civil law, the Liber pauperum, and was an important advisor for Roger.[7]

Roger attended the Council of Tours in 1163, along with a number of other English bishops.[8] Pope Alexander III named Roger a papal legate in February 1164, but his powers did not include the city of Canterbury or anything to do with Archbishop Becket.[9] They did, however, include Scotland.[10]

In late 1164 Roger led a deputation from Henry II that visited the papal court, or curia, to try to persuade Alexander III that any decision on the deposition of Becket should take place in England under a papal legate, rather than in Rome.[11] While Becket was in exile, Roger also managed to secure papal permission for archbishops of York to carry their cross in front of them anywhere in England, a right that had long been a bone of contention between Canterbury and York. Later, the pope rescinded the permission, but consistently refused to give primacy to either Canterbury or York in their struggles.[12]

Roger did not like monks, and William of Newburgh said that he often referred to the foundation of Fountains Abbey as the worst mistake of Archbishop Thurstan's episcopate.[13] Roger also was accused of avarice, and of making unworthy clerical appointments. However, he also started the rebuilding of York Minster, which had been damaged by fire in 1137, built the Archbishop's Palace, York, and helped with the building of a church at Ripon. He also endowed the school at York with an annual income of 100 shillings.[1]

Controversy with Becket

Roger got drawn into the controversy with Becket because Henry II wanted to have his eldest living son crowned as king during Henry's lifetime.(Traditionally, the ceremony is performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury) This was a new practice for England, but was a custom of the Capetian kings of France, which Henry decided to imitate.[14] Henry II insisted that his son, Henry be crowned at Westminster Abbey on 14 June 1170 by Archbishop Roger of York.[9] Also present at the coronation were the bishops of London, Salisbury, Exeter, Chester, Rochester, St Aspah, Llandaff, Durham, Bayeux, Évreux and Sées. The only English bishops absent seem to have been Winchester, Norwich, Worcester, and of course Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was in exile. The remaining English sees were vacant.[15] This overstepped a long tradition which reserved coronations to the Archbishop of Canterbury, a reservation confirmed as recently as 1166 by Pope Alexander III. In 1170, however, Henry II received papal permission to have Roger crown the younger Henry, a permission which Alexander later revoked.[16][17]

Before Becket returned to England, on 1 December 1170, he excommunicated Roger, as well as Gilbert Foliot the Bishop of London and Josceline de Bohon the Bishop of Salisbury. After Becket landed in England the three excommunicates went to Becket and asked for absolution, but while Becket was willing to absolve Gilbert and Josceline, he insisted that only the pope could absolve an archbishop. Roger persuaded the others that they should stick together, and all three went to King Henry in Normandy, to secure the king's permission for their appeals to Rome.[18]

Roger's and his fellow-bishops' stories to Henry are often cited as the spark that touched off the king's anger at Becket and led to his martyrdom. However, it was more probably the stories of Becket's behaviour upon arrival in England that caused Henry's anger, and which indirectly led to the death of Becket.[18] Roger was suspended by Pope Alexander III because he was implicated in Becket's death, but was restored to office on 16 December 1171.[9]

Death and afterwards

Roger died on 26 November 1181[5] and was buried at Durham. Other sources give the date of death as 22 November or 20 November.[9] After Roger's death, the king declared his will invalid and confiscated most of his wealth.[1] Henry's excuse was that bishops' wills made after the bishop became ill, that bequeathed most of their property to charity, were invalid.[19]

Roger had one son, named William, at some point in his career.[9] Some verses in hexameter written by Roger to Maurice of Kirkham, the prior of Kirkham Priory, are extant and have been published as part of Maurice's works.[20] York remained vacant from Roger's death in 1181 until 1189.[21]

Citations

- Barlow "Pont l'Évêque, Roger de" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Greenway "Archdeacons of Canterbury" Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces)

- Barlow Thomas Becket pp. 33–34

- Barlow Thomas Becket p. 35

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 264

- Barlow English Church p. 255

- Stein "Vacarius" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Duggan "From the Conquest to the Death of John" English Church and the Papacy p. 88

- Greenway "Archbishops" Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 6: York

- Duggan "From the Conquest to the Death of John" English Church and the Papacy p. 104

- Warren Henry II p. 490

- Warren Henry II p. 503

- Knowles Monastic Order p. 316

- Warren Henry II pp. 110–111

- Barlow Thomas Becket pp. 206–207

- Powell and Wallis House of Lords pp. 84–85

- Warren Henry II pp. 501–502

- Warren Henry II pp. 507–508

- Barber Henry Plantagenet p. 202

- Sharpe Handlist of Latin Writers p. 594

- Barber Henry Plantagenet p. 219

References

- Barber, Richard (1993). Henry Plantagenet 1133–1189. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 1-56619-363-X.

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Barlow, Frank (1986). Thomas Becket. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07175-1.

- Barlow, Frank (2004). "Pont l'Évêque, Roger de (c.1115–1181)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23961. Retrieved 30 March 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Duggan, Charles (1965). "From the Conquest to the Death of John". In Lawrence, C. H. (ed.). The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages (1999 reprint ed.). Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. pp. 63–116. ISBN 0-7509-1947-7.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Greenway, Diana E. (1999). "Archbishops". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300. Vol. 6: York. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Greenway, Diana E. (1971). "Archdeacons: Canterbury". Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300. Vol. 2: Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces). Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Knowles, David (1976). The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St. Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council, 940–1216 (Second reprint ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05479-6.

- Powell, J. Enoch; Wallis, Keith (1968). The House of Lords in the Middle Ages: A History of the English House of Lords to 1540. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Sharpe, Richard (2001). Handlist of the Latin Writers of Great Britain and Ireland Before 1540. Publications of the Journal of Medieval Latin. Vol. 1 (2001 revised ed.). Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 2-503-50575-9.

- Stein, Peter (2004). "Vacarius (c.1120–c.1200)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28048. Retrieved 16 April 2008. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Warren, W. L. (1973). Henry II. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03494-5.