Taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body by mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word taxidermy describes the process of preserving the animal, but the word is also used to describe the end product, which are called taxidermy mounts or referred to simply as "taxidermy".[1]

The word taxidermy is derived from the Ancient Greek words τάξις taxis (order, arrangement) and δέρμα derma (skin).[2] Thus taxidermy translates to "arrangement of skin".[2]

Taxidermy is practiced primarily on vertebrates[3] (mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and less commonly on amphibians) but can also be done to larger insects and arachnids[4] under some circumstances. Taxidermy takes on a number of forms and purposes including hunting trophies and natural history museum displays. Museums use taxidermy as a method to record species, including those that are extinct and threatened,[5] in the form of study skins and life-size mounts. Taxidermy is sometimes also used as a means to memorialize pets.[6]

A person who practices taxidermy is called a taxidermist. They may practice professionally, catering to museums and sportspeople (hunters and fishers), or as amateurs (hobbyists). A taxidermist is aided by familiarity with anatomy, sculpture, painting, and tanning.

History

Tanning and early stuffing techniques

Preserving animal skins has been practiced for a long time. Embalmed animals have been found with Egyptian mummies. Although embalming incorporates lifelike poses, it is not considered taxidermy. In the Middle Ages, crude examples of taxidermy were displayed by astrologers and apothecaries. The earliest methods of preservation of birds for natural history cabinets were published in 1748 by Reaumur in France. Techniques for mounting were described in 1752 by M. B. Stollas. There were several pioneers of taxidermy in France, Germany, Denmark and England around this time. For a while, clay was used to shape some of the soft parts, but this made specimens heavy.[7][8]

By the 19th century, almost every town had a tannery business.[9] In the 19th century, hunters began bringing their trophies to upholstery shops, where the upholsterers would actually sew up the animal skins and stuff them with rags and cotton. The term "stuffing" or a "stuffed animal" evolved from this crude form of taxidermy. Professional taxidermists prefer the term "mounting" to "stuffing". More sophisticated cotton-wrapped wire bodies supporting sewn-on cured skins soon followed. In France, Louis Dufresne, taxidermist at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle from 1793, popularized arsenical soap in an article in Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle (1803–1804). This technique enabled the museum to build an immense collection of birds.[10]

Dufresne's methods spread to England in the early 19th century, where updated and non-toxic methods of preservation were developed by some of the leading naturalists of the day, including Rowland Ward and Montague Brown.[11] Ward established one of the earliest taxidermy firms, Rowland Ward Ltd. of Piccadilly. However, the art of taxidermy remained relatively undeveloped, and the specimens remained stiff and unconvincing.[12]

Taxidermy as art

The Victorian era marked a significant period for taxidermy, during which mounted animals gained popularity as integral elements of interior design and decoration.[13] English ornithologist John Hancock is widely regarded as a key figure in the development of modern taxidermy.[14] Hancock, an enthusiastic bird collector who personally hunted his specimens, adopted techniques involving clay modeling and plaster casting.

Illustrating his impact, Hancock presented a collection of stuffed birds at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. This display garnered substantial attention from both the public and the scientific community, which recognized the specimens as advancements over earlier models due to their lifelike and artistic qualities.[15] A judge's comment during the exhibition praised Hancock's work for elevating taxidermy to a level comparable to other esteemed arts.[16]

Hancock's exhibit contributed to a surge of interest in taxidermy across the nation, leading to the rapid growth of amateur and professional collections available for public viewing. This trend was particularly pronounced in middle-class Victorian households, with even Queen Victoria amassing an impressive collection of birds. Notably, taxidermy was increasingly employed by grieving pet owners to commemorate their deceased companions.[17]

Anthropomorphic taxidermy

In the late 19th century, a style known as anthropomorphic taxidermy became popular. A 'Victorian whimsy', mounted animals were dressed as people or displayed as if engaged in human activities. An early example of this genre was displayed by Herman Ploucquet, from Stuttgart, Germany, at the Great Exhibition in London.[18]

The best-known practitioner in this genre was the English taxidermist Walter Potter, whose most famous work was The Death and Burial of Cock Robin. Among his other scenes were "a rat's den being raided by the local police rats ... [a] village school ... featuring 48 little rabbits busy writing on tiny slates, while the Kittens' Tea Party displayed feline etiquette and a game of croquet."[19] Apart from the simulations of human situations, he had also added examples of bizarrely deformed animals such as two-headed lambs and four-legged chickens. Potter's museum was so popular that an extension was built to the platform at Bramber railway station.[20]

Other Victorian taxidermists known for their iconic anthropomorphic taxidermy work are William Hart and his son Edward Hart.[21] They gained recognition with their famous series of dioramas featuring boxing squirrels. Both William and Edward created multiple sets of these dioramas. One 4-piece set of boxing squirrel dioramas (circa 1850) sold at auction in 2013 for record prices. The four dioramas were created as a set (with each diorama portraying the squirrels at a different stage during their boxing match); however, the set was broken up and each was sold separately at the same auction. The set was one of a number they created over the years featuring boxing squirrels.[21]

Famous examples of modern anthropomorphic taxidermy include the work of artist Adele Morse, who gained international attention with her "Stoned Fox" sculpture series,[22] and the work of artist Sarina Brewer, known for her Siamese twin squirrels and flying monkeys partaking in human activities.[23]

20th century

.jpg.webp)

In the early 20th century, taxidermy was taken forward under the leadership of artists such as Carl Akeley, James L. Clark, William T. Hornaday, Coleman Jonas, Fredrick, and William Kaempfer, and Leon Pray. These and other taxidermists developed anatomically accurate figures which incorporated every detail in artistically interesting poses, with mounts in realistic settings and poses that were considered more appropriate for the species. This was quite a change from the caricatures popularly offered as hunting trophies.

Additional modern uses of Taxidermy have been the use of "Faux Taxidermy" or fake animal heads that draw on the inspiration of traditional taxidermy. Decorating with sculpted fake animal heads that are painted in different colors has become a popular trend in interior design.[24]

Rogue taxidermy

Rogue taxidermy (sometimes referred to as "taxidermy art"[25]) is a form of mixed media sculpture.[23][26] Rogue taxidermy art references traditional trophy or natural history museum taxidermy, but is not always constructed out of taxidermied animals;[23][26] it can be constructed entirely from synthetic materials.[23][27] Additionally, rogue taxidermy is not necessarily figurative, as it can be abstract and does not need to resemble an animal.[23] It can be a small decorative object or a large-scale room-sized installation. There is a very broad spectrum of styles within the genre, some of which falls into the category of mainstream art.[23][28] "Rogue taxidermy" describes a wide variety of work, including work that is classified and exhibited as fine art.[27] Neither the term, nor the genre, emerged from the world of traditional taxidermy.[26] The genre was born from forms of fine art that utilize some of the components found in the construction of a traditional taxidermy mount.[26] The term "rogue taxidermy" was coined in 2004 by an artist collective called The Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists.[27][29] The Minneapolis-based group was founded by artists Sarina Brewer, Scott Bibus, and Robert Marbury as a means to unite their respective mediums and differing styles of sculpture.[29][30] The definition of rogue taxidermy set forth by the individuals who formed the genre (Brewer, Bibus, and Marbury) is: "A genre of pop-surrealist art characterized by mixed media sculptures containing conventional taxidermy-related materials that are used in an unconventional manner".[25][31][32] Interest in the collective's work gave rise to an artistic movement referred to as the Rogue Taxidermy art movement, or alternately, the Taxidermy Art movement.[26][31][33][34] Apart from describing a genre of fine art,[26][23][33] the term "rogue taxidermy" has expanded in recent years and has also become an adjective applied to unorthodox forms of traditional taxidermy such as anthropomorphic mounts and composite mounts where two or more animals are spliced together.[35][36] (e.g.; sideshow gaffs of conjoined "freak" animals and mounts of jackalopes or other fictional creatures) In addition to being the impetus for the art movement, the inception of the genre also marked a resurgence of interest in conventional (traditional) forms of taxidermy.[35][36]

Methods

Traditional skin-mount

The methods taxidermists practice have been improved over the last century, heightening taxidermic quality and lowering toxicity. The animal is first skinned in a process similar to removing the skin from a chicken prior to cooking. This can be accomplished without opening the body cavity, so the taxidermist usually does not see internal organs or blood. Depending on the type of skin, preserving chemicals are applied or the skin is tanned. It is then either mounted on a mannequin made from wood, wool and wire, or a polyurethane form. Clay is used to install glass eyes and can also be used for facial features like cheekbones and a prominent brow bone. Modeling clay can be used to reform features as well, if the appendage was torn or damaged clay can hold it together and add muscle detail. Forms and eyes are commercially available from a number of suppliers. If not, taxidermists carve or cast their own forms.[37]

Taxidermists seek to continually maintain their skills to ensure attractive, lifelike results. Mounting an animal has long been considered an art form, often involving months of work; not all modern taxidermists trap or hunt for prized specimens.[38]

Animal specimens can be frozen, then thawed at a later date to be skinned and tanned. Numerous measurements are taken of the body. A traditional method that remains popular today involves retaining the original skull and leg bones of a specimen and using these as the basis to create a mannequin made primarily from wood wool (previously tow or hemp wool was used) and galvanised wire. Another method is to mould the carcass in plaster, and then make a copy of the animal using one of several methods. A final mould is then made of polyester resin and glass cloth, from which a polyurethane form is made for final production. The carcass is then removed and the mould is used to produce a cast of the animal called a 'form'. Forms can also be made by sculpting the animal first in clay. Many companies produce stock forms in various sizes. Glass eyes are then usually added to the display, and in some cases, artificial teeth, jaws, tongue, or for some birds, artificial beaks and legs can be used.

Freeze-dried mount

An increasingly popular trend is to freeze-dry the animal. For all intents and purposes, a freeze-dried mount is a mummified animal. The internal organs are removed during preparation; however, all other tissue remains in the body. (The skeleton and all accompanying musculature is still beneath the surface of the skin) The animal is positioned into the desired pose, then placed into the chamber of a special freeze-drying machine designed specifically for this application. The machine freezes the animal and also creates a vacuum in the chamber. Pressure in the chamber helps vaporize moisture in the animal's body, allowing it to dry out. The rate of drying depends on vapor pressure. (The higher the pressure, the faster the specimen dries.)[39] Vapor pressure is determined by the temperature of the chamber; the higher the temperature, the higher the vapor pressure is at a given vacuum.[39] The length of the dry-time is important because rapid freezing creates less tissue distortion (i.e.; shrinkage, warping, and wrinkling)[39] The process can be done with reptiles, birds, and small mammals such as cats, rodents, and some dogs. Large specimens may require up to six months in the freeze dryer before they are completely dry. Freeze-drying is the most popular type of pet preservation. This is because it is the least invasive in terms of what is done to the animal's body after death, which is a concern of owners (Most owners do not opt for a traditional skin mount). In the case of large pets, such as dogs and cats, freeze-drying is also the best way to capture the animal's expression as it looked in life (another important concern of owners). Freeze-drying equipment is costly and requires much upkeep. The process is also time-consuming; therefore, freeze-drying is generally an expensive method to preserve an animal. The drawback to this method is that freeze-dried mounts are extremely susceptible to insect damage. This is because they contain large areas of dried tissue (meat and fat) for insects to feed upon. Traditional mounts are far less susceptible because they contain virtually no residual tissues (or none at all). Regardless of how well a taxidermy mount is prepared, all taxidermy is susceptible to insect damage. Taxidermy mounts are targeted by the same beetles and fabric moths that destroy wool sweaters and fur coats and that infest grains and flour in pantries.[40]

Reproduction mount

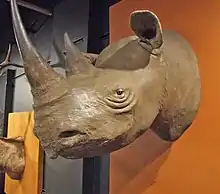

Some methods of creating a trophy mount do not involve preserving the actual body of the animal. Instead, detailed photos and measurements are taken of the animal so a taxidermist can create an exact replica in resin or fiberglass that can be displayed in place of the real animal. No animals are killed in the creation of this type of trophy mount. One situation where this is practiced is in the world of sport fishing where catch and release is becoming increasingly prevalent. Reproduction mounts are commonly created for (among others) trout, bass, and large saltwater species such as the swordfish and blue marlin. Another situation where reproduction trophies are created is when endangered species are involved. Endangered and protected species, such as the rhinoceros, are hunted with rifles loaded with tranquilizer darts rather than real bullets. While the animal is unconscious, the hunter poses for photos with the animal while it is measured for the purpose of creating a replica, or to establish what size of prefabricated fiberglass trophy head can be purchased to most closely approximate the actual animal. The darted animal is not harmed. The hunter then displays the fiberglass head on the wall in lieu of the real animal's head to commemorate the experience of the hunt.

Re-creation mount

Re-creation mounts are accurate life-size representations of either extant or extinct species that are created using materials not found on the animal being rendered. They utilize the fur, feathers, and skin of other species of animals. According to the National Taxidermy Association: "Re-creations, for the purpose of this [competition] category, are defined as renderings which include no natural parts of the animal portrayed. A re-creation may include original carvings and sculptures. A re-creation may use natural parts, provided the parts are not from the species being portrayed. For instance, a re-creation eagle could be constructed using turkey feathers, or a cow hide could be used to simulate African game".[41] A famous example of a re-creation mount is a giant panda created by taxidermist Ken Walker that he constructed out of dyed and bleached black bear fur.[42]

Study skins

A study skin is a taxidermic zoological specimen prepared in a minimalistic fashion that is concerned only with preserving the animal's skin, not the shape of the animal's body.[43] As the name implies, study skins are used for scientific study (research), and are housed mainly by museums. A study skin's sole purpose is to preserve data, not to replicate an animal in a lifelike state.[43] Museums keep large collections of study skins in order to conduct comparisons of physical characteristics to other study skins of the same species. Study skins are also kept because DNA can be extracted from them when needed at any point in time.[44]

A study skin's preparation is extremely basic. After the animal is skinned, fat is methodically scraped off the underside of the hide. The underside of the hide is then rubbed with borax or cedar dust to help it dry faster. The animal is then stuffed with cotton and sewn up. Mammals are laid flat on their belly. Birds are prepared lying on their back. Study skins are dried in these positions to keep the end product as slender and streamlined as possible so large numbers of specimens can be stored side-by-side in flat file drawers, while occupying a minimum amount of space.[45] Since study skins are not prepared with aesthetics in mind they do not have imitation eyes like other taxidermy, and their cotton filling is visible in their eye openings.[46]

1. Measurements are collected

1. Measurements are collected 2. Animal is Skinned. Notes on internal organs are recorded

2. Animal is Skinned. Notes on internal organs are recorded 3. Skin is stuffed with cotton

3. Skin is stuffed with cotton 4. Completed study skin is labeled with a data tag

4. Completed study skin is labeled with a data tag

Notable taxidermists

- Carl Akeley (1864–1926), the father of modern taxidermy

- Jean-Baptiste Bécœur (1718–1777), French ornithologist, taxidermist, and inventor of arsenical soap

- Harry Ferris Brazenor (1863–1948), 19th-century British taxidermist

- James Dickinson, MBE (1959–), retired British taxidermist, known for his restorations of existing specimens

- William Temple Hornaday (1854–1937), American zoologist, conservationist, and taxidermist who was the first director of what is now called the Bronx Zoo

- Martha Maxwell (1831–1881), American naturalist, taxidermist, and artist who was the first female naturalist to obtain and taxidermy her own specimens

- Charles Johnson Maynard (1845–1929), American naturalist, ornithologist, and taxidermist who discovered many new species and authored many notable publications

- Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), American painter, Revolutionary War veteran, inventor, naturalist, and polymath who organized the US's first scientific expedition in 1801

- Walter Potter (1835–1918), Victorian era British creator of iconic whimsical anthropomorphic taxidermy dioramas

- Jules Verreaux (1807–1873), French botanist, ornithologist, and taxidermy collector and trader

- James Rowland Ward (1848–1912), British taxidermist and founder of Rowland Ward Limited, known for its furniture and household items made of animal parts

See also

- Bird collections

- Conservation and restoration of taxidermy

- Deyrolle, internationally known purveyor of taxidermy located Paris

- Green hunting

- Negro of Banyoles, example of a taxidermied human

- Julia Pastrana, a sideshow performer preserved via taxidermy

- Plastination

- Skinning

- Skull mounts

- Taxidermy art and science

References

- "Learning to Look: Taxidermy in Museums – MSU Museum". Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- Harper, Douglas. "taxidermy". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Stephen P. Rogers; Mary Ann Schmidt; Thomas Gütebier (1989). An Annotated Bibliography on Preparation, Taxidermy, and Collection Management of Vertebrates with Emphasis on Birds. Carnegie Museum of Natural History. ISBN 978-0-911239-32-4.

- Daniel Carter Beard (1890). The American Boys Handy Book. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 242, 243.

- "Life After Death: Extinct Animals Immortalized With Taxidermy". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- Pierce, Jessica (January 5, 2012). "Would You Like Your Pet Stuffed, Freeze-dried, or Cryonically Preserved?". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Péquignot, Amandine (2006). "The History of Taxidermy: Clues for Preservation". Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals. 2 (3): 245–255. doi:10.1177/155019060600200306. ISSN 1550-1906. S2CID 191989601.

- Mantagu Browne (31 July 2015). Practical Taxidermy – A Manual of Instruction to the Amateur in Collecting, Preserving, and Setting up Natural History Specimens. Read Country Book. ISBN 978-1-4733-7689-2.

- Taxidermy Vol.12 Tanning – Outlining the Various Methods of Tanning. Read Books Limited. 26 August 2016. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-4733-5355-8.

- C. J. Maynard (25 August 2017). Manual of Taxidermy – A Complete Guide in Collecting and Preserving Birds and Mammals. Read Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-4733-3900-2.

- "11 Things You Probably Didn't Know About Taxidermy". 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- Taxidermy Vol.10 Collecting Specimens – The Collection and Displaying Taxidermy Specimens. Tobey Press. 26 August 2016. ISBN 978-1-4733-5354-1.

- Davie, Oliver (1900). Methods in the art of taxidermy. Philadelphia: David McKay.

- Leon Pray (31 July 2015). Taxidermy. Read Books Limited. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-1-4733-7688-5.

- "John Hancock: A Biography by T. Russell Goddard (1929)". Archived from the original on 2013-12-14.

- "Taxidermy Articles".

- "Morbid Outlook – Memento Mori Animalia".

- Henning, Michelle (2007). "Anthropomorphic taxidermy and the death of nature: The curious art of Hermann Ploucquet, Walter Potter and Charles Waterton" (PDF). Victorian Literature and Culture. 35 (2): 663–678. doi:10.1017/S1060150307051704. S2CID 59405158.

- Morris, Pat (7 December 2007). "Animal magic". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- Ketteman, Tony. "Mr Potter of Bramber". Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- "Stuffed Squirrels Fight for High Prices". Kovels.com. Kovels Auction House. 2 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Robert Marbury (2014). Taxidermy Art: A Rogue's Guide to the Work, the Culture, and How to Do It Yourself. Artisan. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-57965-558-7.

- Rivera, Erica (8 April 2016). "Crave Profile: Sarina Brewer and Rogue Taxidermy". CraveOnline. CraveOnlineLLC. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "HuffPost is now a part of Verizon Media". HuffPost. 9 May 2013.

- Ode, Kim (15 October 2014). "Rogue Taxidermy, at the crossroads of art and wildlife". Variety section. Star Tribune. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Lundy, Patricia (16 February 2016). "The Renaissance of Handcrafts and Fine Arts Celebrates Dark Culture". Dirge magazine. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Langston, Erica (30 March 2016). "When Taxidermy Goes Rogue". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "The Curious Occurrence Of Taxidermy In Contemporary Art". Brown University. David Winton Bell Gallery. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Voon, Claire (14 October 2014). "Women Are Dominating the Rogue Taxidermy Scene". Vice. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Topcik, Joel (3 January 2005). "Head of Goat, Tail of Fish, More Than a Touch of Weirdness". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Gyldenstrom, Freja (17 June 2017). "Mortality and Taxidermy in Art". culturised.co.uk. Culturised. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "The History of Rogue Taxidermy". The Taxidermy Art of Sarina Brewer. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Evans, Hayley (22 February 2016). "Rogue Taxidermy Artists Who Create Imaginative Sculptures". illusion magazine. Scene 360 LLC. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Niittynen, Miranda (2015). "Animal Magic; Sculpting Queer Encounters through Rogue Taxidermy Art" (PDF). Gender Forum: Internet Journal for Gender Studies. 55: 14–34. ISSN 1613-1878. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Leggett, David (7 April 2017). "Chimaera Taxidermy – The Weird and the Wonderful". CataWiki. CataWiki Auction House. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Dead Animals into Art". CBC Radio. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Melissa Milgrom (8 March 2010). Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-48705-2.

- Morgan Mathews (director) (2005). Taxidermy: Stuff the World (documentary film). Century Films.

- "Feeze Dry Taxidermy". freezedryco.com. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- "Identifying Museum Insect Pest damage" (PDF). National Park Service. November 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "World Taxidermy Competition categories". Taxidermy.net. Breakthrough Magazine, Inc. 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Rowell, Meloday (14 September 2014). "Exotic, Extinct, and On Display: Robert Clark's Take on Taxidermy". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Study Skins". ciMuseums.org.uk. Colchester & Ipswich Museums. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Kurihara, Nozomi (11 February 2013). "Utility of hair shafts from study skins for mitochondrial DNA analysis". Genetics and Molecular Research. 12 (4): 5396–5404. doi:10.4238/2013.November.11.1. PMID 24301912.

- "Taxidermy". Queensland Museum Network. The State Queensland. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Rogers, Steve. "Relaxing Skins". Bird Collections Bulletin Board. Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

Further reading

- Rookmaaker, L. C.; et al. (2006). "The ornithological cabinet of Jean-Baptiste Bécoeur and the secret of the arsenical soap" (PDF). Archives of Natural History. 33 (1): 146–158. doi:10.3366/anh.2006.33.1.146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

External links

| Library resources about Taxidermy |

Media related to Taxidermy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Taxidermy at Wikimedia Commons- Taxidermy.blog

- Taxidermy.Net

- Methods in the Art of Taxidermy by Oliver Davie

- Free Taxidermy School.Com