Centuriation

Centuriation (in Latin centuriatio or, more usually, limitatio[1]), also known as Roman grid, was a method of land measurement used by the Romans. In many cases land divisions based on the survey formed a field system, often referred to in modern times by the same name. According to O. A. W. Dilke,[2] centuriation combined and developed features of land surveying present in Egypt, Etruria, Greek towns and Greek countryside.

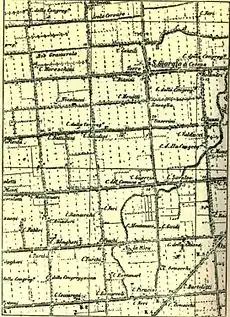

Centuriation is characterised by the regular layout of a square grid traced using surveyors' instruments. It may appear in the form of roads, canals and agricultural plots. In some cases these plots, when formed, were allocated to Roman army veterans in a new colony, but they might also be returned to the indigenous inhabitants, as at Orange (France).[3]

The study of centuriation is very important for reconstructing landscape history in many former areas of the Roman empire.

History

The Romans began to use centuriation for the foundation, in the fourth century BCE, of new colonies in the ager Sabinus, northeast of Rome. The development of the geometric and operational characteristics that were to become standard came with the founding of the Roman colonies in the Po valley, starting with Ariminum (Rimini) in 268 BCE.[4]

The agrarian law introduced by Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BCE, which included the privatisation of the ager publicus, gave a great impetus to land division through centuriation.[5]

Centuriation was used later for land reclamation and the foundation of new colonies as well as for the allocation of land to veterans of the many civil wars of the late Republic and early Empire, including the battle of Philippi in 42 BCE. This is mentioned by Virgil, in his Eclogues, when he complains explicitly about the allocation of his lands near Mantua to the soldiers who had participated in that battle.

Centuriation was widely used throughout Italy and also in some provinces. For example, careful analysis has identified, in the area between Rome and Salerno, 80 different centuriation systems created at different times.[6]

System and procedure

Various land division systems were used, but the most common was known as the ager centuriatus system.

The surveyor first identified a central viewpoint, the umbilicus. He then took up his position there and, looking towards the west, defined the territory with the following names:

- ultra, the land he saw in front of him;

- citra, the land behind him;

- dextera, the land to his right;

- sinistra, the land to his left.

He then traced the grid using an instrument known as a groma, tracing two road axes perpendicular to each other:

- the first, generally oriented east–west, was called decumanus maximus, which was traced taking as reference the place where the sun rose in order to know exactly where east was;[7]

- the second, with a north–south orientation, was called cardo maximus.

Measurement instruments

- Groma

- Chorobates for levels

- Dioptra for levels and angles of slopes

Orientation

It has been suggested that the Roman centuriation system inspired Thomas Jefferson's proposal to create a grid of townships for survey purposes, which ultimately led to the United States Public Land Survey System. The similarity of the two systems is empirically obvious in certain parts of Italy, for example, where traces of centuriation have remained.[8]

However, Thrower points out that, unlike the later US system, "not all Roman centuriation displays consistent orientation".[9]

This is because, for practical reasons, the orientation of the axes did not always coincide with the four cardinal points and followed instead the orographic features of the area, also taking into account the slope of the land and the flow of rainwater along the drainage channels that were traced (centuriation of Florentia (Florence). In other cases, it was based on the orientation of existing lines of communication (centuriation along the Via Emilia) or other geomorphological features.

Centuriation is typical of flat land, but centuriation systems have also been documented in hilly country.

Centuriation of the surrounding territory

Sometimes the umbilicus agri was located in a city or a castrum. This central point was generally referred to as groma, from the name of the instrument used by the gromatici (surveyors).

In such cases, the grid was traced by extending the urban cardo maximus and the decumanus maximus through the gates of the city into the surrounding agricultural land.

Parallel secondary roads (limites quintarii) were then traced on both sides of the initial axes at intervals of 100 actus (about 3.5 km). The territory was thus divided into square areas.

The road network density was then increased with other roads parallel to those already traced at a distance from each other of 20 actus (710.40 m). Each of the square areas – 20 × 20 actus – resulting from this further division was called a centuria or century.

This 200 jugera area of the centuria became prevalent in the period when the large areas of the Po Valley were delimited, while smaller centuries of 10 × 10 actus, as the name centuria suggests, had formerly been used.[10] Contemporary Roman sources as well as modern archeological results suggest that centuria varied in size from 50 to 400 jugera, with some subdivisions using non-square plots.[11]

| Road widths in Roman feet (29.6 cm) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Width | Equivalent | Name |

| 40 Roman feet | 11.84 m | decumanus maximus |

| 20 Roman feet | 5.92 m | cardo maximus |

| 12 Roman feet | 3.55 m | limites quintarii |

| 8 Roman feet | 2.37 m | Other roads |

The land was divided after the completion of the roads.

Each century was divided into 10 strips, lying parallel to the cardo and the decumanus, with a distance between them of 2 actus (71.04 m), thus forming 100 squares (heredia) of about 0.5 hectares each: 100 heredia = 1 centuria.

Each heredium was divided in half along the north–south axis thus creating two jugera: one jugerum, from jugum (yoke), measured 2523 square metres, which was the amount of land that could be ploughed in one day by a pair of oxen.

Regions where centuriation was used

Even today, in some parts of Italy, the landscape of the plain is determined by the outcome of Roman centuriation, with the persistence of straight elements (roads, drainage canals, property divisions) which have survived territorial development and are often basic elements of urbanisation, at least until the twentieth century, when the human pressure of urban growth and infrastructures destroyed many of the traces scattered throughout the agricultural countryside.

Significant examples of centuriation in Italy

- Cesena, and in particular the country to the north-east and north-west of the city;

- Central Romagna;

- Padua, eastern area of the province; in this area of Venetia, the geometrical layout of the landscape is known as the Graticolato Romano;

- Ager Campanus (Acerra, Capua, Nola, Atella);

- Florence (Florentia), first century CE, in the plain to the west to Prato and beyond.

- Province of Bergamo: There are still several easily identifiable traces, from the low plain almost to the foot of the hills, for example, the straight road of about ten kilometres between Spirano and Stezzano, through Comun Nuovo; there are also traces of agricultural centuriation identifiable in the street network of Treviglio.[12]

Traces of centuriation in Gallia Narbonensis (Southern France)

- Béziers

- Valence

- Orange (Orange B)

Traces of centuriation in Hispania Tarraconensis

- Tarragona

- Empúries

- Girona

- Barcelona

- Cerdanya

- Isona (Pallars Jussà)

- Guissona

- Lleida

- els Prats de Rei (antiga Segarra romana)

- la Seu d'Urgell o Castellciutat (probable)

- Bages (probable)

- Castell-rosselló (probable)

Traces of centuriation in Britannia (present-day southern and central Britain)

- Ripe, Sussex (probable)

- Great Wymondley, Hertfordshire (Roman field system identified, possibly part of a cadastre)[13]

- Worthing, Sussex (probable)

See also

- Ancient Roman units of measurement

- Ancient Roman architecture,

- Roman roads

- Drainage and centuriation in the Po Valley and Po delta

- Ager Romanus

- Aerial archaeology

References

- Dilke The Roman Land Surveyors, p. 134

- Dilke The Roman Land Surveyors, p. 34

- Piganiol, Les documents cadastraux de la colonie romaine d'Orange, XVIe supplément à Gallia, Paris, 1962.

- Laffi Studi di storia romana e di diritto, p. 415, 2001

- Laffi Studi di storia romana e di diritto, p. 416

- Libertini, Persistenza di luoghi e toponimi nelle terre delle antiche città di Atella e Acerrae

- Bell, Castra et urbs romana

- "XyHt - a magazine for geospatial professionals".

- Thrower, Maps & civilization, p. 25

- Umberto Laffi op. cit., page 415, 2001

- Flach 1990, pp. 14–15.

- Maps with text in Italian: http://www.provincia.bergamo.it/provpordocs/D0_02_05.pdf Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Applebaum, S. "The Pattern of Settlement in Roman Britain." The Agricultural History Review 11, no. 1 (1963): 1-14. Accessed September 4, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40273036.

Bibliography

In English:

- Bell, Anders (2001). "Castra et urbs romana: An Examination of the Common Features of Roman Settlements in Italy and the Empire and a System to aid in the Discovery of their Origins". CAC Undergraduate Essay Contest for 2000-2001. Classical Association of Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2011-10-01.

- Oswald A. W. Dilke The Roman Land Surveyors, 1992 (1971), ISBN 90-256-1000-5

- Norman Joseph William Thrower, Maps & civilization: cartography in culture and society, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1972

In Italian:

- Umberto Laffi, Studi di storia romana e di diritto, 2001, ISBN 88-87114-70-6

- Giacinto Libertini, Persistenza di luoghi e toponimi nelle terre delle antiche città di Atella e Acerrae, 1999

In French:

- A. Piganiol, « Les documents annexes du cadastre d'Orange », CRAI, 1954, 98–3, p. 302–310 lire en ligne

In German:

- Flach, D. (1990). Römische Agrargeschichte. Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft (in German). Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-33989-9. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

Further reading

In English:

- Blair, John; Rippon, Stephen; Smart, Christopher (2020). Planning in the Early Medieval Landscape. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-78962-116-7.

- Kerridge, Ronald; Standing, Michael (2005). Worthing. Teffont: The Francis Frith Collection. ISBN 978-1-85937-995-0.

In Catalan and Spanish:

- L'Avenç. Revista d'Història, núm. 167, febrer 1993. Dossier: "Els cadastres en època romana. Història i recerca", pàgs. 18–57.

- E. Ariño – J. M. Gurt – J. M. Palet, El pasado presente. Arqueología de los paisajes en la Hispania romana, Universidad de Salamanca – Universitat de Barcelona, Salamanca – Barcelona, 2004. ISBN 84-475-2804-9

In French:

- A. Caillemer, R. Chevalier, « Les centuriations de l'Africa vetus », Annales, 1954, 9–4, p. 433–460 lire en ligne

- André Chastagnol, « Les cadastres de la colonie romaine d'Orange », Annales, 1965, 20–1, p. 152–159 lire en ligne

- Col., « Fouilles d'un limes du cadastre B d'Orange à Camaret (Vaucluse) », DHA, 17–2, 1991, p. 224 lire en ligne

- Gérard Chouquer, François Favory, Les Paysages de l'Antiquité. Terres et cadastres de l'occident romain, Errance, Paris, 1991, 243 p.

- Gérard Chouquer, « Un débat méthodologique sur les centuriations », DHA, 1993, 19–2, p. 360–363 lire en ligne

- Claire Marchand, « Des centuriations plus belles que jamais ? Proposition d'un modèle dynamique d'organisation des formes », Études Rurales, 167–168, 2003, 3–4, p. 93–113 lire en ligne.

- L.R. Decramer, R. Elhaj, R. Hilton, A. Plas, « Approches géométrique des centuriations romaines. Les nouvelles bornes du Bled Segui », Histoire et Mesure, XVII, 1/2, 2002, p. 109–162 lire en ligne

- Gérard Chouquer, « Les transformations récentes de la centuriation. Une autre lecture de l'arpentage romain », Annales, 2008–4, p. 847–874.