Rotary International

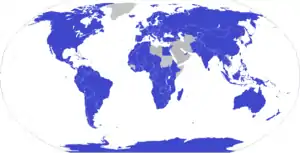

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. The mission of Rotary, as stated on its website, is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through [the] fellowship of business, professional, and community leaders".[1] It is a non-political and non-religious organization.[2] Membership is by application or invitation and based on various social factors. There are over 46,000[3] member clubs worldwide, with a membership of 1.4 million individuals, known as Rotary members.[4]

| |

Headquarters in Evanston, Illinois, United States | |

| Formation | February 23, 1905 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Paul P. Harris |

| Type | Service club |

| Headquarters | Evanston, Illinois, United States |

| Location |

|

Membership | 1.4 million |

Official language | English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish |

President | Gordon R. McInally (July 2023 – June 2024) |

Key people | John Hewko (CEO & General Secretary) |

| Publication | The Rotarian |

| Website | www |

History

The first years of the Rotary Club

The first Rotary Club was formed when attorney Paul P. Harris called together a meeting of three business acquaintances in downtown Chicago, United States, at Harris's friend Gustave Loehr's office in the Unity Building on Dearborn Street on February 23, 1905.[5][6] In addition to Harris and Loehr (a mining engineer and freemason[7]), Silvester Schiele (a coal merchant), and Hiram E. Shorey (a tailor) were the other two who attended this first meeting. The members chose the name Rotary because initially they rotated subsequent weekly club meetings to each other's offices, although within a year, the Chicago club became so large it became necessary to adopt the now-common practice of a regular meeting place.

The next four Rotary Clubs were organized in cities in the western United States, beginning with San Francisco,[8] then Oakland, Seattle,[9] and Los Angeles.[10] The National Association of Rotary Clubs in America was formed in 1910.[11][12] On November 3, 1910, a Rotary club began meeting in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, marking the beginning of Rotary as an international organisation.[13] On 22 February 1911, the first meeting of the Rotary Club Dublin was held in Dublin, Ireland.[14] This was the first club established outside of North America. In April 1912, Rotary chartered the Winnipeg club marking the first establishment of an American-style service club outside the United States.[15][16]: 45 To reflect the addition of a club outside of the United States, the name was changed to the International Association of Rotary Clubs in 1912.[17]

In August 1912, the Rotary Club of London received its charter from the Association, marking the first acknowledged Rotary club outside North America. It later became known that the Dublin club in Ireland was organized before the London club, but the Dublin club did not receive its charter until after the London club was chartered. During World War I, Rotary in Britain increased from 9 to 22 clubs,[18] and other early clubs in other nations included those in Cuba in 1916, the Philippines in 1919 and India in 1920.

In 1922, the name was changed to Rotary International.[16] From 1923 to 1928, Rotary's office and headquarters were located on E 20th Street (now E Cullerton Street) in the Atwell Building.[19] During this same time, the monthly magazine The Rotarian was published mere floors below by Atwell Printing and Binding Company.[20] By 1925, Rotary had grown to 200 clubs with more than 20,000 members.[21] During the 1930s there was an expanding conflict in Asia between Japan and China and the fear of a confrontation between Japan and the United States. In hopes of helping resolve these issues, a leading Japanese international statesman Prince Iyesato Tokugawa was chosen as the Honorary Keynote Speaker at Rotary's Silver (25th) Anniversary Convention/Celebration held in 1930 in Chicago. Prince Tokugawa held the influential position of president of Japan's upper house of congress the Diet for 30 years. Tokugawa promoted democratic principles and international goodwill. It was only after his passing in 1940 that Japanese militants were able to push Japan into joining the Axis Powers in WWII.[22][23]

World War II era in Europe

Rotary Clubs in Spain ceased to operate shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.[24]

Clubs were disbanded across Europe as follows:[24]

- Netherlands (1923)[25]

- Finland (1926)

- Austria (1938)

- Italy (1939)[26]

- Czechoslovakia (1940)

- Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Yugoslavia and Luxembourg (1941)

- Hungary (1941/1942)

Rotary International has worked with the UN since the UN started in 1945. At that time Rotary was involved in 65 countries. The two organizations shared ideals around promoting peace. Rotary received consultative status at the UN in 1946–47.[27]

During the Third Reich, Rotary Clubs were grouped with Freemasonry as secret societies associated with Jews, and Nazi officials were banned from joining them. This was reversed in July 1933 after appeals but the club was forced to ban all Jews from membership. This led to several non-Jews quitting in solidarity. In order to survive the members tried to show their loyalty to the Nazi leadership, inviting government officials and high standing businesspeople like Hermann Schlosser who was a business manager for Degesch which supplied Zyklon B for use at death camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau. After 1945, the Rotary club tried to control the damage by preventing members such as Hans Globke and Wolfgang A. Wick from being appointed presidents.[28]

From 1945 onward

Rotary clubs in Eastern Europe and communist nations were disbanded by 1945–46, but new Rotary clubs were organized in many other countries, and by the time of the national independence movements in Africa and Asia, the new nations already had Rotary clubs. After the relaxation of government control of community groups in Russia and former Soviet satellite nations, Rotarians were welcomed as club organizers, and clubs were formed in those countries, beginning with the Moscow club in 1990.

In 1985, Rotary launched its PolioPlus program to immunize all of the world's children against polio. As of 2011, Rotary had contributed more than 900 million US dollars to the cause.[29]

As of 2006, Rotary had more than 1.4 million members in over 36,000 clubs among 200 countries and geographical areas, making it the most widespread by branches and second largest service club by membership, behind Lions Clubs International.[30] The number of Rotarians has slightly declined in recent years: Between 2002 and 2006, they went from 1,245,000 to 1,223,000 members. North America accounts for 450,000 members, Asia for 300,000, Europe for 250,000, Latin America for 100,000, Oceania for 100,000 and Africa for 30,000.

Rotary International Presidents 2001–present

- Richard D. King (2001–02)

- Bhichai Rattakul (2002–03)

- Jonathan B. Majiyagbe (2003–04)

- Glenn E. Estess, Sr. (2004–05)

- Carl-Wilhelm Stenhammar (2005–06)

- William Boyd (2006–07)

- Wilfrid J. Wilkinson (2007–08)

- Dong Kurn Lee (2008–09)

- John Kenny (2009–10)

- Ray Klinginsmith (2010–11)

- Kalyan Banerjee (2011–12)

- Sakuji Tanaka (2012–13)

- Ron D. Burton (2013–14)

- Gary C.K. Huang (2014–15)

- K.R. Ravindran (2015–16)

- John F. Germ (2016–17)

- Ian H. S. Riseley (2017–18)

- Barry Rassin (2018–19)

- Mark Daniel Maloney (2019–20)

- Holger Knaack (2020–21)

- Shekhar Mehta (2021–22)

- Jennifer E. Jones (2022–23)

- Gordon McInally (2023–24)

Other notable past Presidents

- Jim Emmerling (1908–09)

- Paul P. Harris (1910–12)

- Clinton Presba Anderson (1932–33)

- Herbert J. Taylor (1954–55)

- Nitish Chandra Laharry (1962–63)

- Richard L. Evans (1966–67)

- Luther H. Hodges (1967–68)

- Sir Clem Renouf (1978–79)

- Carlos Canseco (1984–85)

- Royce Abbey (1988–89)

Organization and administration

In order to carry out its service programs, Rotary is structured in club, district and international levels. Rotarians are members of their clubs. The clubs are chartered by the global organization Rotary International (RI) headquartered in Evanston, Illinois. For administrative purposes, the more than 46,000 clubs worldwide are grouped into 529 districts, and the districts into 34 zones.

Rotary Clubs

The Rotary Club is the basic unit of Rotary activity, and each club determines its own membership. Clubs originally were limited to a single club per city, municipality, or town, but Rotary International has encouraged the formation of one or more additional clubs in the largest cities when practical. Most clubs meet weekly, usually at a mealtime on a weekday in a regular location, when Rotarians can discuss club business and hear from guest speakers. Each club also conducts various service projects within its local community, and participates in special projects involving other clubs in the local district, and occasionally a special project in a "sister club" in another nation. Most clubs also hold social events at least quarterly and in some cases more often.

Each club elects its own president and officers among its active members for a one-year term. The clubs enjoy considerable autonomy within the framework of the standard constitution and the constitution and bylaws of Rotary International. The governing body of the club is the Club Board (sometimes called Club Council), consisting of the club president (who serves as the Board chairman), a president-elect, club secretary, club treasurer, and several Club Board directors, including the immediate past president and the President Elect. The president usually appoints the directors to serve as chairs of the major club committees, including those responsible for club service, vocational service, community service, youth service, and international service.

Rotarians may attend any Rotary club around the world at one of their weekly meetings.

Rotaract Clubs

Rotaract: It is an organization of young adults (university age and young professionals) who take action through community and international service, learn leadership skills, and participate in professional development. Rotaract clubs are either community or university based. "Rotaract" stands for "Rotary in Action", and its motto is "Self Development – Fellowship through Service".

Rotaract began as a program of Rotary International, and its first club was founded in 1968 by Charlotte North Rotary Club,[31] located in Charlotte, North Carolina.

In 2019, Rotaract went from being a program of Rotary International to being a membership type of Rotary International, elevating its status to resemble that of Rotary clubs. As of 1 July 2020, Rotaract clubs can exist on their own, or may be sponsored by Rotary and/or Rotaract clubs. This makes them true "partners in service" and key members of the family of Rotary.[32] A Rotaract club may, but is not required to, establish upper age limits, provided that the club (in accordance with its bylaws) obtain the concurrence of its members and the sponsor club(s) (if sponsored).

District level

A District Governor (DG), who is an officer of Rotary International and represents the RI board of directors in the field, leads their respective Rotary district. Each DG is nominated by the clubs of their district, and elected by all the clubs meeting in the annual RI District Conference held each year. The DG appoints Assistant Governors (AGs) from among the Rotarians of the district to assist in the management of Rotary activity and multi-club projects in the district. AGs act as liaisons between the DG and the clubs, to make communication flow more smoothly throughout the District.[33]

As part of a DG's duties, they must visit every club in their District at least once during their year as DG in order to spread the RI President's message and theme for that year. The AGs are assigned specific clubs to be under their purview, and they must accompany the DG on their official club visits to those particular clubs.[34]

Zone level

Approximately 15 Rotary districts form a zone. A zone director, who serves as a member of the RI board of directors, heads two zones. The zone director is nominated by the clubs in the zone and elected by the convention for the terms of two consecutive years.

Rotary International

Rotary International is governed by a board of directors composed of the international president, the president-elect, the general secretary, and 17 zone directors. The nomination and the election of each president is handled in the one- to three-year period before the president takes office, and is based on requirements including geographical balance among Rotary zones and previous service as a district governor and board member. The international board meets quarterly to establish policies and make recommendations to the overall governing bodies, the RI Convention and the RI Council on Legislation.

Rotary International President

Rotary’s president presides over the Board of Directors and is elected to a one-year term.

CURRENT PRESIDENT: R. Gordon R. McInally is president of Rotary International. He was educated at the Royal High School in Edinburgh and at the University of Dundee, where he earned his graduate degree in dental surgery. He operated his own dental practice in Edinburgh until 2016. Gordon was chair of the East of Scotland branch of the British Paedodontic Society and has held various academic positions. He has also served as a presbytery elder, chair of the Queensferry parish congregational board, and commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.[35]

- General Secretary/ CEO

Rotary International has a general secretary, who also acts as chief executive officer and leads the Rotary Foundation. The current holder of the post is John Hewko.[36]

Membership

According to its constitutions ("Charters"), Rotary defines itself as a non-partisan, non-sectarian organization. Membership is open to "adult persons who demonstrate good character, integrity, and leadership; possess good reputation within their business, profession, occupation, and/or community."[37]

One can contact a Rotary club to inquire about membership and it was a traditional method that a person can join a Rotary club only if invited; there is the ability to join without an invitation but it is recommended to attend a meeting to ensure a suitable fit to the club.[38]

Active membership

Active membership is by invitation from a current Rotarian, to professionals or businesspersons working in diverse areas of endeavour. Each club may limit up to ten percent of its membership representing each business or profession in the area it serves. The goal of the clubs is to promote service to the community they work in, as well as to the wider world. Many projects are organised for the local community by a single club, but some are organised globally.

Honorary membership

Clubs may award honorary membership in recognition of a person's distinguished efforts in furtherance of Rotary ideals or otherwise in support of Rotary's cause. As the highest distinction a Rotary club can confer on an individual, it is exercised only in exceptional cases. Honorary members are exempt from the payment of admission fees and dues. They have no voting privileges and are not eligible to hold any office in their club. Honorary membership is time-limited and terminates automatically at the end of the term, usually one year. It may be extended for an additional period or may also be revoked at any time. Examples of honorary members are heads of state or former heads of state, scientists, members of the military, and other famous figures.[39] However, as each club may establish different rules for honorary members, there will be some variation in terms of selection and privileges of honorary members.[40]

Female membership

From 1905 until the 1980s, women were not allowed membership in Rotary clubs, although Rotarian spouses, including Paul Harris's wife Jean, were often members of the similar "Inner Wheel" club. Women did play some roles, and Jean Thomson Harris made numerous speeches. Dale Carnegie's biographer Carlos Roberto Bacila describes that in 1955 when women were not permitted to attend Rotary meetings, the Brooklyn Rotary Club made an exception and finally allowed Marilyn Burke, Carnegie's secretary, to accompany him in a lecture inside the Rotary. In 1963, it was noted that the Rotary practice of involving wives in club activities had helped to break down female seclusion in some countries.[41]: 58–62 Clubs such as Rotary were predated by women's service organisations, which started in the United States as early as 1790.[16]: 50

The first Irish clubs discussed admitting women as members in 1912, but the proposal foundered over issues of social class. Gender equity in Rotary moved beyond the theoretical question when in 1976, the Rotary Club of Duarte, California, admitted three women as members. After the club refused to remove the women from membership, Rotary International revoked the club's charter in 1978. The Duarte club filed suit in the California courts, claiming that Rotary Clubs are business establishments subject to regulation under California's Unruh Civil Rights Act, which bans discrimination based on race, gender, religion or ethnic origin. Rotary International then appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. The RI attorney argued that "... [the decision] threatens to force us to take in everyone, like a motel".[42] The Duarte Club was not alone in opposing RI leadership; the Seattle-International District club unanimously voted to admit women in 1986. The United States Supreme Court, on 4 May 1987, confirmed the Californian decision supporting women, in the case Board of Directors, Rotary International v. Rotary Club of Duarte.[43] Rotary International then removed the gender requirements from its requirements for club charters, and most clubs in most countries have opted to include women as members of Rotary Clubs.[42][44] The first female club president to be elected was Sylvia Whitlock of the Rotary Club of Duarte, California in 1987.[45] By 2007, there was a female trustee of Rotary's charitable wing The Rotary Foundation while female district governors and club presidents were common.

Women currently account for 22% of international Rotary membership.[46] In 2013, Anne L. Matthews, a Rotarian from South Carolina, began her term as the first female vice-president of Rotary International. Also in 2013, Nan McCreadie was appointed as the first female president of Rotary International in Great Britain and Ireland (RIBI).[47] The first woman to join Rotary in Ghana, West Africa was Hilda Danquah (Rotary Club of Cape Coast) in 1992. The first woman president in Ghana was Dr. Naana Agyeman-Mensah in 2001 (Rotary Club of Accra-Airport). Up until 2013, there has been 46 women presidents in the 30 Rotary clubs in Ghana. In 2013, Stella Dongo from Zimbabwe was appointed District Governor for District 9210 (Zimbabwe/Zambia/Malawi/Northern-Mozambique) for the Rotary year 2013–14 making her the first female District Governor in the region. She had previously held the offices of Assistant Governor (2006–08), District Administrator (2008–09) and President of The Rotary Club of Highlands (2005–06). She was also Zimbabwe's Country Coordinator (2009–10). Stella, who is a Master PRLS 5 Graduate has been recognised and awarded various District awards including Most Able President for year 2005–06 and Assistant Governor of the year 2006–07 and a Paul Harris Fellow. The first female to be President of Rotary International will be Jennifer E. Jones of the Windsor Roseland Rotary Club in Windsor, Ontario Canada.

The change of the second Rotarian motto in 2004, from "He profits most who serves best" to "They profit most who serve best", 99 years after its foundation, illustrates the move to general acceptance of women members in Rotary.

Racial and sexual orientation diversity

The first Rotary Clubs in Asia were in Manila[48] in the Philippines and Shanghai in China, each in July 1919. Rotary's office in Illinois immediately began encouraging the Rotary Club of Shanghai to recruit Chinese members "believing that when a considerable number of the native business and professional men have been so honoured, the Shanghai Club will begin to realize its period of greatest success." As part of considering the application of a Club to be chartered in Kolkata (then Calcutta), India in January 1920 and Tokyo, Japan in October 1920, Rotary formally considered the issue of racial restriction in membership and determined that the organization could not allow racial restrictions to the organization's growth. In Rotary's legislative deliberations in June 1921, it was formally determined that racial restrictions would not be permitted. Non-racialism was included in the terms of the standard constitution in 1922 and required to be adopted by all member Clubs.

Rotary and other service clubs in the last decade of the 20th century became open to gay members.[49]

Affiliates

Rotary Clubs sponsor a number of affiliated clubs that promote the goals of Rotary in their community.

Inner Wheel Clubs

Inner Wheel is an international organization founded in 1924 to unite wives and daughters of Rotarians. Inner Wheel Clubs exist in over 103 countries. Like Rotary, Inner Wheel is divided into local clubs and districts. Female spouses of Rotary members are traditionally called "Partners" or "Spouse".

Programs and activities of Rotary International

Rotary concentrates on seven areas: promoting peace, improving health through disease prevention and treatment, improving the health of mothers and children, water and sanitation, education, economic development, and supporting the environment.[50]

PolioPlus

The most notable current global project, PolioPlus, is contributing to the global eradication of polio. Sergio Mulitsch di Palmenberg (1923–1987), Governor of RI District 204 (1984–1985), founder of the RC of Treviglio and Pianura Bergamasca (Italy), was the man who inspired and promoted the RI PolioPlus vaccination campaign.[51] Mulitsch made it possible shipping the first 500,000 doses of antipolio vaccine to the Philippines at the beginning of 1980.[52] This project later gave rise to the NGO "Nuovi Spazi al Servire" co-ordinated by Luciano Ravaglia (RC Forlì, Italy).[53] Since beginning the project in 1985, Rotarians have contributed over US$850 million and hundreds of thousands of volunteer-hours, contributing to the inoculation of more than two billion of the world's children. Inspired by Rotary's commitment, the World Health Organization (WHO) passed a resolution in 1988 to eradicate polio by 2000. Now a partner in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) with WHO, UNICEF and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Rotary is recognized by the United Nations as the key private partner in the eradication effort.

In 2008, Rotary received a $100 million challenge grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Rotary committed to raising $100 million. In January 2009, Bill Gates announced a second challenge grant of $255 million. Rotary again committed to raising another $100 million. In total, Rotary will raise $200 million by 30 June 2012. Together, the Gates Foundation and Rotary have committed $555 million toward the eradication of polio. At the time of the second challenge grant, Bill Gates said:

We know that it's a formidable challenge to eradicate a disease that has killed and crippled children since at least the time of the ancient Egyptians. We don't know exactly when the last child will be affected. But we do have the vaccines to wipe it out. Countries do have the will to deploy all the tools at their disposal. If we all have the fortitude to see this effort through to the end, then we will eradicate polio.[54]

There has been some limited criticism concerning the program for polio eradication. There are some reservations regarding the adaptation capabilities of the virus in some of the oral vaccines, which have been reported to cause infection in populations with low vaccination coverage.[55] As stated by Vaccine Alliance, however, in spite of the limited risk of polio vaccination, it would neither be prudent nor practicable to cease the vaccination program until there is strong evidence that "all wild poliovirus transmission [has been] stopped". In a 2006 speech at the Rotary International Convention, held at the Bella Center in Copenhagen, Bruce Cohick stated that polio in all its known wild forms would be eliminated by late 2008, provided efforts in Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India all proceed with their current momentum. As of October 2012, Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan still had wild polio, but it had been eliminated in India.[56]

In 2014, polio survivor and Rotarian Ramesh Ferris met with the Dalai Lama to discuss the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. The meeting went viral via a selfie taken by Ferris with the Dalai Lama.[57]

Interact

Interact is Rotary International's service club for young people ages 12 to 18. Interact clubs are sponsored by Rotary clubs (and may be co-sponsored by Rotaract clubs), which provide support and guidance, but they are self-governing and self-supporting.

Club membership varies greatly. Clubs can be single gender or mixed, large or small. They can draw from the student body of a single school or from two or more schools in the same community, and welcome home-schooled students.

Each year, Interact clubs complete at least two community service projects, one of which furthers international understanding and goodwill. Through these efforts, Interactors develop a network of friendships with local and overseas clubs and learn the importance of

- Developing leadership skills and personal integrity

- Demonstrating helpfulness and respect for others

- Understanding the value of individual responsibility and hard work

- Advancing international understanding and goodwill

As one of the most significant and fastest-growing programs of Rotary service, with more than 15,000 clubs in more than 145 countries and geographical areas, Interact has become a worldwide phenomenon. Almost 340,000 young people are involved in Interact. Interact stands for “International Action”.

RYLA

RYLA, or Rotary Youth Leadership Awards, is a leadership program for young people aged 14 to 30. The Rotary Youth Leadership Awards program offers Rotarians an opportunity to personally participate in developing qualities of leadership, good citizenship, and personal and professional development in the young people of their communities. RYLA program content and format can be customized to target limited age groups in order to address varying needs and interests within the community.

Rotary Community Corps

The Rotary Community Corps (RCC) is a volunteer organization which facilitates non-Rotarians who want to help meet community needs. As of 2021, there were close to 12,000 RCC members in over 100 countries.[58]

Exchanges and scholarships

Some of Rotary's most visible programs include Rotary Youth Exchange (RYE), a student exchange program for students in secondary education. The Rotary Foundation's oldest program, Ambassadorial Scholarships ended in 2013. Effective July 2009, the Rotary Foundation previously ended funding for the Cultural and Multi-Year Ambassadorial Scholarships as well as Rotary Grants for University Teachers.[59]

Rotary Fellowships, paid by the foundation launched in honor of Paul Harris in 1947, specialize in providing graduate fellowships around the world, usually in countries other than their own in order to provide international exposure and experience to the recipient.[41]: 62

Recently, a new program was established known as the Rotary peace and Conflict Resolution program which provides funds for two years of graduate study in one of eight universities around the world. Rotary is naming about 75 of these scholars each year. The applications for these scholarships are found on line but each application must be endorsed by a local Rotary Club. Children and other close relatives of Rotarians are not eligible.

Adults up to the age of 30 may participate in New Generations Service Exchange for up to six months and may be organized for individuals or groups. The minimum age of the participants shall be the age of majority in the host country, but not be younger than age 18. New Generations Service Exchanges must have a strong humanitarian or vocational service component.

Rotary Peace Centers

Starting in 2002, The Rotary Foundation partnered with eight universities around the world to create the Rotary Centers for International Studies in peace and conflict resolution. The universities included International Christian University (Japan), University of Queensland (Australia), Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) (France), University of Bradford (UK), Universidad del Salvador (Argentina), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (US), Duke University (US), and University of California, Berkeley (US) Since then, the Rotary Foundation's Board of Trustees has dropped its association with the Center in France at the Paris Institute of Political Studies, the Center in Argentina at the Universidad del Salvador, and the Center in the US at the University of California. In 2006, a new Rotary Peace Center at Chulalongkorn University (Thailand) began offering a three-month professional development program in peace and conflict studies for mid-level and upper-level professionals. In 2011, the Rotary Peace Center at Uppsala University (Sweden) was established and began offering a two-year master's program in peace and conflict studies.

Up to 100 Rotary Peace Fellows are selected annually to earn either a professional development certificate in peace and conflict studies or a master's degree in a range of disciplines related to peace and security. Each Rotary Peace Center offers a unique curriculum and field-based learning opportunities that examine peace and conflict theory through a variety of different frameworks. The first class graduated in 2004.[60] As with many such university programs in "peace and conflict studies", questions have been raised concerning political bias and controversial grants. The average grant was about $75,000 per fellow for the two-year program and $12,000 per fellow for the three-month certificate program.[61]

Literacy programs

Rotary clubs worldwide place a focus on increasing literacy. Such importance has been placed on literacy that Rotary International has created a "Rotary Literacy Month" that takes place during the month of March.[62] Rotary clubs also aim to conduct many literacy events during the week of September 8, which is International Literacy Day.[63] Some Rotary clubs raise funds for schools and other literacy organizations. Many clubs take part in a reading program called "Rotary Readers", in which a Rotary member spends time in a classroom with a designated student, and reads one-on-one with them.[64] Some Rotary clubs participate in book donations, both locally and internationally.[65] As well as participating in book donations and literacy events, there are educational titles written about Rotary Clubs and members, such as Rotary Clubs Help People, Carol is a Rotarian by Rotarian and children's book author Bruce Larkin and "Rhoda's Rescue" by Maine author Barbara Walsh in conjunction with Rotary Club of Waterville, Maine's Rhoda Reads early literacy program.

Publications

Rotary International publishes an official monthly magazine now named Rotary in English (first published in 1911 as The National Rotarian). From April 1923 to August 1928, the official magazine was managed and printed from the same building – the Atwell Building – as Rotary's office and headquarters;[19][20] the building was designed for Atwell Printing and Binding Company by famed Chicago architect, Alfred S. Alschuler.[66]

Other periodicals are independently produced in more than 20 different major languages and distributed in 130 countries. One of them is Rotary Norden which is distributed in four language editions in five countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.[67]

Honors

- Honorary-Member of the Order of Merit, Portugal (2 February 2005)[68]

See also

References

Citations

- "What is Rotary". Rotary International. Archived from the original on 9 June 2000. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Olivo, Antonio (2015-06-28). "In changing times, Rotary Clubs wrestle over prayer". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- "Join". www.rotary.org. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- "About Rotary". rotary.org.

- De Grazia, Victoria (2005). Irresistible Empire: America's Advance Through 20th-Century Europe. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-674-01672-6.

- Sipari, Lorenzo Arnone (2006). Spirito rotariano e impegno associativo nel Lazio meridionale: i Rotary Club di Frosinone, Cassino e Fiuggi, 1959–2005 [Rotarian Spirit and Commitment in Southern Lazio: the Rotary Clubs of Frosinone, Cassino and Fiuggi, 1959–2005] (in Italian). Cassino: University of Cassino Press. p. 15.

- Lewis, Basil (7 July 2003). "Gus Loehr". Rotary Global History Fellowship. Archived from the original on 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

- Rotary International (November 2008). "The Rotarian". Rotary. Rotary International: 46. ISSN 0035-838X.

- "Our History | Rotary Club of Seattle – Seattle 4". Rotary Club of Seattle. 16 April 2018.

- "Our History | LA5 Rotary Club of Los Angeles". LA5 Rotary Club of Los Angeles. 16 April 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- District 5950 Rotary International (1 May 2009). Rotary International: Almost a Century 1910–2007. AuthorHouse. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4389-0584-6.

- Proceedings: Twenty-Eighth Annual Convention of Rotary International. Rotary International. p. 1.

- "Rotary Goes Global". Rotary International. Archived from the original on 16 August 2001. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - S. Padraig Walsh (1 January 1979). The First Rotarian: The Life and Times of Paul Percy Harris, Founder of Rotary. Scan Books. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-906360-02-6.

On 22 February 1911 the Rotary Club of Dublin was formed by formal resolution, with Morrow himself as the organizing secretary.

- Lorimer, Wesley C. (February 1980). "The Club that made Rotary international: The Jump to Winnipeg". The Rotarian: 70. ISSN 0035-838X.

- Wikle, Thomas A. (Summer 1999). "International Expansion of the American-Style Service Club". Journal of American Culture. 22 (2): 45–52. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1999.2202_45.x.

- "Expanding Our Reach (1912-1930)".

- Lewis, Basil (2003-07-03). "Rotary in World War 1". Rotary Global History Fellowship. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01.

- "Rotary History: A Home for Headquarters". 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- "The Rotarian Archives". RotaryInternational. 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Rosemarie T. Downer (1 March 2009). The Self-Scarred Church. Xulon Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-60791-473-0.

- Katz, Stan S. (2019). The Art of Peace: an illustrated biography on Prince Tokugawa. Horizon Productions. pp. Chapter 8.

- "Introduction to The Art of Peace: the illustrated biography of Prince Iyesato Tokugawa". TheEmperorAndTheSpy.com. 13 April 2020.

- Lewis, Basil (2003-03-16). "The Onset of War Closed Clubs in the 1930s and 1940s". Rotary Global History Fellowship. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07.

- Rotary International (March 1996). "The Rotarian". Rotary. Rotary International: 23. ISSN 0035-838X.

- Maria Teresa Antonia Morelli, «Al di sopra delle nazioni e dei partiti». Rotary italiano e regime fascista 1923–1938, in "Le Carte e la Storia, Rivista di storia delle istituzioni" 2/2021, pp. 63–78, doi: 10.1411/102910

- "Rotary – University of Oregon-UNESCO Crossings Institute". unesco.uoregon.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

- Wiesen, S. J. (2009). "Service Above Self? Rotary Clubs, National Socialism, and Transnational Memory in the 1960s and 1970s". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 23: 1–25. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcp017. S2CID 145767613.

- "Progress Against Polio". ONE. April 2, 2011. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Charles, Jeffrey A. (1993). Service Clubs in American Society: Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions. p. 4. ISBN 9780252020155. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- "The Birthplace of Rotaract". Charlotte North Rotary Club. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "Rotaract, Interact, and RYLA". Rotary International. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Governor". my.rotary.org. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "Governor". my.rotary.org. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- "Our Leaders". www.rotary.org.

- "John Hewko: General Secretary/CEO—Rotary International and The Rotary Foundation". Ukrainian Catholic Education Foundation. May 24, 2019. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- "Constitution of Rotary International". Rotarian International. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- Rotary International. "Joining Rotary is by invitation only". Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "Honorary Club Member".

- Hewko, John (May 2019). "2019 Council on Legislation of Rotary International Report of Action 14–18 April 2019". Rotary International. Retrieved 2021-05-09.

attached file: co19_report_of_action_en.pdf

- Bird, John. "The Wonderful, Wide, Backslapping World Of Rotary." Saturday Evening Post, 2/9/1963, Vol. 236, Issue 5

- Stuart Taylor Jr. (1987-05-05). "High Court Rules that Rotary Clubs Must Admit Women". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "Board of Directors, Rotary International v. Rotary Club of Duarte". Rotary International v. Rotary Club. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Rotary eClub One Makeup". rotaryeclubone.org.

- Hanf, Susan; Polydoros, Donna (1 October 2009). "Historic Moments: Women in Rotary". Rotary International News. Rotary International. Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- Rotary International Online Member Data 12 June 2017

- Lake, Howard. "Nan McCreadie to become Rotary's first female president." UK Fundraising. 25 June 2013. http://www.fundraising.co.uk/news/2013/06/25/nan-mccreadie-become-rotary039s-first-female-president#sthash.KfC2sc6p.dpuf

- "Rotary Club of Manila's 100 years celebration organized". The Philippine Star. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2022 – via PressReader.

- Quittner, Jeremy. "Join the Club." Advocate, 4/16/2002, Issue 861

- Dochterman, Clifford L. (2012). ABCs of Rotary, Fifth edition, 2012. Rotary International. p. 7.

- Forward, David C. A Century of Service: The Story of Rotary International. Published by Rotary International. Evanston, IL: 2009. First edition 2003. ISBN 0915062224.

- Franco Pellaschiar, "Corrispondenza, atti, attestati e stralci di documenti sull'impegno di Sergio Mulitsch per l'Operazione PolioPlus". In Realtà Nuova, anno LXVII, n. 3, Milano, 2003.

- Luciano Ravaglia, "L'eredità di Sergio Mulitsh: "Nuovi spazi al servire", l'Istituto Ong fra rotariani italiani". In Realtà Nuova, anno LXVII, n. 3, Milano, 2003.

- "Bill Gates – Rotary International". www.GatesFoundation.org. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 2009-01-21. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

- Brown, Phyllida (December 2002). "Polio: can immunization ever stop?". Immunization Focus. Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. Archived from the original on 2003-02-03. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- "Global Polio Eradication Initiative > Home". polioeradication.org.

- Kotecha, Nisha. "Best Selfie Ever." Good News Shared. http://goodnewsshared.com/best-selfie-ever

- Rotary Community Corps: 2021 Annual Survey Result (Report). 9 February 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "Scholarship Programs History". Rotary District 7780: Southern Maine and Seacoast New Hampshire. Archived from the original on 2015-12-07. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "Rotary Centers for International Studies in peace and conflict resolution". Rotary International. Archived from the original on 2006-02-12. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Makerere hosts Africa's Rotary Peace Centre, to offer full scholarships". newvision.co.ug. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "Rotary Literacy Month: One of the 3 Rs under test." Rotary Times. 29 March 2007. http://rotarytimes1280.typepad.com/rotary_times/2007/03/rotary_literacy.html Access date 17 June 2012.

- "International Literacy Day – 8 September". United Nations. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Rotary Reader Brochure" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- "2009–10 Literacy Resource Group:Guide to Literacy Service Projects and Awards for Clubs" (PDF). 31 March 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010.

- "Atwell Printing Company Building". Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archive. Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- Maj-Britt Höglund (2015). "The Absent Female Rotarian in Finland: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Rotary Norden". In Tiina Mäntymäki; Marinella Rodi-Risberg; Anna Foka (eds.). Deviant Women: Cultural, Linguistic and Literary Approaches to Narratives of Femininity (PDF). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 157. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-03319-9. ISBN 978-3-631-64329-7.

- "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas". Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

Sources

- "2019–20 Rotary president selected". www.rotary.org. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

Further reading

- Charles, Jeffrey A. (1993). Service Clubs in American Society: Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252020155.

- Goff, Brendan. Rotary International and the Selling of American Capitalism (Harvard University Press, 2021); emphasis on the international aspects of Rotary International.

- Lewis, Su Lin, "Rotary International's 'Acid Test': Multi-ethnic Associational Life in 1930s Southeast Asia," Journal of Global History, 7 (July 2012), 302–34.