Ruguanxue

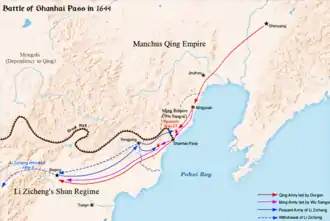

Ruguanxue (Chinese: 入关学; lit. 'breakthrough studies') is a nationalistic, memetic discourse on the Chinese Internet that likens the United States to the declining Ming dynasty and China to the powerful, barbarian Qing dynasty, and believes that China will "break through the Shanhai Pass" and take over the position of the United States.

Etymology

The term was coined by Chinese netizen Shangaoxian (山高县, a pseudonym) in 2019, when he wrote a 300-word answer to a question on Zhihu (the Chinese equivalent of Quora), "What history lessons have the Chinese learned from the death of Ming?", which received more than 4,000 likes. In particular, he wrote, "Don't carry sage books and think nonsense before you break through the pass, and after you break through the pass, there will always be Confucian masters for you to use," arguing that it is useless to try to win public opinion when the ruling empire (referring to the United States) thinks you are a barbarian, and it is better to take America's place and build one's own values.[1] Shangaoxian later said his theory was also inspired by the German Empire's challenge to the 19th century colonial order.[2]

In addition to the term itself, as well as the Qing and Ming dynasties, Chinese netizens have used many other metaphors and references to enrich the discourse, such as comparing the Strait of Malacca to the Shanhai Pass, complete westernization to shaving and changing clothes, and breaking through the Shanhai Pass to breaking through the Straits of Malacca and the American blockade associated with it.[3]

The popularity of the discourse is generally believed to be related to the rise of Chinese nationalism at the time, although the discursive, metaphorical approach used has been traced back much further in time to online groups.[4]

Views

United States and international relations

Almost all advocates believe that the United States is in decline and that China should take its place, while American accusations against China are seen as resistance from a weakened empire against an emerging one.[5] The theoretical foundation of this discourse is considered to be constructed on geopolitics, and the central issue it addresses is the transfer of international leadership.[6]

Shangaoxian himself compares China to the German Empire and the Japanese Empire. He said that both of them were the losers who advocate Ruguanxue, and specifically analyzed that Wilhelm II wanted to have a "colony under the sun" but failed, while China had a population of 1.4 billion so it would not fail.[2] Although the anti-hegemonic sentiment and realpolitik analysis contained in this is supported, it is also accused of being ultra-nationalistic and reminiscent of Ichisada Miyazaki's militaristic sentiment.[7] Debate persists as to whether or not it is an imperialist discourse, with it being said to be still in the "open" stage, still focused only on China's challenge to the American order, without considering what might happen if that challenge becomes successful.[8]

COVID-19

COVID-19 brought about accusations against China, but Chinese netizens believe that China did a good job of controlling the outbreak and therefore the outbreak elsewhere is not their responsibility. Shangaoxian himself accused Wuhan Diary of smearing China and criticized the U.S. for its confusion in dealing with the pandemic.[9]

Culture

Despite being regarded as a "barbarian" nation, it is perceived more as a desire to gain a cognitive discourse of its own and to change its "barbarian" status by getting other nations to recognize it.[10] The leading advocates claim that this refers to "our state of being in a world dominated by North American slave-owning gangs [sic], not that we are really barbarians. Ruguan refers to the path of breaking the slave-owning gangs' system of domination."[11]

References

- Yang 2021; Zhang 2020, pp. 112.

- Kong 2020, p. 28.

- Buckley 2020; Ma 2020, p. 57.

- Buckley 2020; Yao 2020, p. 35.

- Kong 2020, p. 27; Wong 2021.

- Kong 2020, p. 25; Ma 2020, p. 56.

- Kong 2020, p. 25; Fu 2020, p. 40.

- Kong 2020, p. 26; Fu 2020, p. 40.

- Fu 2020, p. 42; Yang 2020, p. 64.

- Fu 2020, p. 44; Kong 2020, p. 26.

- Fu 2020, p. 44; Yang 2020, p. 67.

Sources

- Buckley, Chris (14 December 2020). "China's Combative Nationalists See a World Turning Their Way". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Fu, Zheng (2020). "国家与个体的双重边缘处境——"入关学"的不满情绪及其困境" [The Double Marginal Situation of the State and the Individual: The Discontent and Dilemma of "Ruguanxue"] (PDF). Dongfang Journal (in Simplified Chinese): 39–46. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Kong, Yuan (2020). ""入关"与"伐纣":关于中国崛起的两种知识论图景" ["Breakthrough the pass" and "Conquering the Zhou": Two Intellectual Pictures of China's Rise] (PDF). Dongfang Journal (in Simplified Chinese): 25–31. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Ma, Yifan (2020). ""入关学"的话语生成结构及其出路" [The Discursive Structure of "Ruguanxue" and its Way Out] (PDF). Dongfang Journal (in Simplified Chinese) (9): 53-63. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Wong, Brian Y. S. (6 April 2021). "China Has an Image Problem—but Knows How to Fix It". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Yang, Yuan (20 April 2021). "China's keyboard warriors like to fight . . . each other". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Yang, Bowen (2020). "对"入关学"的宪法社会学思考:国际体系与国内宪制塑造" [Constitutional Sociological Reflections on "Ruguanxue": International System and Domestic Constitutional Shaping] (PDF). Dongfang Journal (in Simplified Chinese) (9): 64-71. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Yao, Yunfan (2020). "从"网络政见"到"网络键政"——修辞学视野中的"入关学"" [From "Internet Political Opinions" to "Internet Keyboard Politics" – The Rhetorical Perspective of "Ruguanxue"] (PDF). Dongfang Journal (in Simplified Chinese) (9): 32-38. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Zhang, Yiwu (2020). ""入关学"的思考" [Reflections on "Ruguanxue"]. Zhongguancun (in Simplified Chinese) (12): 112–113. Retrieved 8 August 2022.