Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls

The Papal Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls (Italian: Basilica Papale di San Paolo fuori le Mura) is one of Rome's four major papal basilicas,[lower-alpha 1] along with the basilicas of Saint John in the Lateran, Saint Peter's, and Saint Mary Major, as well as one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome.

| Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls | |

|---|---|

| Papal Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls | |

The statue of Saint Paul in front of the portico | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°51′31″N 12°28′36″E | |

| Location | Piazzale San Paolo, Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Tradition | Latin Church |

| Website | Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls |

| History | |

| Status | Papal major basilica |

| Dedication | Paul the Apostle |

| Consecrated | AD 4th century |

| Relics held | Saint Paul |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Luigi Poletti (reconstruction) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Neoclassical |

| Groundbreaking | AD 4th century |

| Completed | 1840 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 150 metres (490 ft) |

| Width | 80 metres (260 ft) |

| Nave width | 30 metres (98 ft) |

| Height | 73 metres (240 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Rome |

| Clergy | |

| Archpriest | James Michael Harvey |

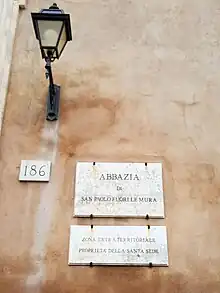

| Official name | Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in that City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori le Mura |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Reference no. | 91 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Basilica is within Italian territory, but the Holy See owns the Basilica in a regime of extraterritoriality, with Italy recognizing its full ownership and conceding it "the immunity granted by international law to the headquarters of the diplomatic agents of foreign States".[1][2][3]

James Michael Cardinal Harvey was named Archpriest of the basilica in 2012.

History

The basilica was founded by the Roman Emperor Constantine I over the burial place of Paul of Tarsus, where it was said that, after the apostle's execution, his followers erected a memorial, called a cella memoriae. This first basilica was consecrated by Pope Sylvester in 324.[4]

In 386, Emperor Theodosius I began erecting a much larger and more beautiful basilica with a nave and four aisles with a transept. It was probably consecrated around 402 by Pope Innocent I. The work, including the mosaics, was not completed until Leo I's pontificate (440–461). In the 5th century, it was larger than the Old Saint Peter's Basilica. The Christian poet Prudentius, who saw it at the time of emperor Honorius (395–423), describes the splendours of the monument in a few expressive lines.

Under Leo I, extensive repair work was carried out following the collapse of the roof on account of fire or lightning. In particular, the transept (i.e. the area around Paul's tomb) was elevated and a new main altar and presbytery were installed. This was probably the first time that an altar was placed over the tomb of Saint Paul, which remained untouched, but largely underground given Leo's newly elevated floor levels. Leo was also responsible for fixing the triumphal arch and for restoring a fountain in the courtyard (atrium).

Under Pope Gregory the Great (590–604), the main altar and presbytery were extensively modified. The pavement in the transept was raised and a new altar was placed above the earlier altar erected by Leo I. The position was directly over Saint Paul's sarcophagus.

In that period, there were two monasteries near the basilica: Saint Aristus's for men and Saint Stefano's for women. Masses were celebrated by a special body of clerics instituted by Pope Simplicius. Over time, the monasteries and the basilica's clergy declined; Pope Gregory II restored the former and entrusted the monks with the basilica's care.

The basilica was damaged in an earthquake on 29 April 801. Its roof collapsed, but was rebuilt by Leo III.

As it lay outside the Aurelian Walls, the basilica was damaged in the 9th century during a Saracen raid. Consequently, Pope John VIII (872–82) fortified the basilica, the monastery, and the dwellings of the peasantry,[5] forming the town of Johannispolis (Italian: Giovannipoli) which existed until 1348, when an earthquake totally destroyed it.

In 937, when Odo of Cluny came to Rome, Alberic II of Spoleto, Patrician of Rome, entrusted the monastery and basilica to his congregation and Odo placed Balduino of Monte Cassino in charge. Pope Gregory VII was abbot of the monastery and in his time Pantaleone, a rich merchant of Amalfi who lived in Constantinople, presented the bronze doors of the basilica maior, which were executed by Constantinopolitan artists; the doors are inscribed with Pantaleone's prayer that the "doors of life" may be opened to him.[6] Pope Martin V entrusted it to the monks of the Congregation of Monte Cassino. It was then made an abbey nullius. The abbot's jurisdiction extended over the districts of Civitella San Paolo, Leprignano, and Nazzano, all of which formed parishes.

%252C_Kreuzgang_des_Klosters.jpg.webp)

The graceful cloister of the monastery was erected between 1220 and 1241.

From 1215 until 1964, it was the seat of the Latin Patriarch of Alexandria.

Pope Benedict XIV undertook the restoration of the apse mosaic and the frescoes of the central nave, and commissioned the painter Salvatore Manosilio to continue the series of papal portraits, which at that time ended with Pope Vitalian, who had reigned over a millennium earlier.[7]

On 15 July 1823, a workman repairing the copper gutters of the roof started a fire that led to the near-total destruction of this basilica, which, alone among all the churches of Rome, had preserved much of its original character for 1435 years.[4] Marble salvaged from the burnt-out Saint Paul's was re-laid for the floor of Santo Stefano del Cacco.[8]

In 1825, Leo XII issued the encyclical Ad plurimas encouraging donations for the reconstruction. A few months later, he issued orders that the basilica be rebuilt exactly as it had been when new in the fourth century, though he also stipulated that precious elements from later periods, such as the medieval mosaics and tabernacle, also be repaired and retained. These guidelines proved unrealistic for a variety of reasons and soon ceased to be enforced. The result is a reconstructed basilica that bears only a general resemblance to the original and is by no means identical to it. The reconstruction was initially entrusted to the architect Pasquale Belli, who was succeeded upon his death in 1833 by Luigi Poletti,[9] who supervised the project until his death in 1869 and was responsible for the lion's share of the work. Many elements which had survived the fire were reused in the reconstruction.[4] Many foreign rulers also made contributions. Muhammad Ali Pasha, Viceroy of Egypt gave columns of alabaster, while the Emperor of Russia donated precious malachite and lapis lazuli that was used on some of the altar fronts. The transept and high altar were consecrated by Pope Gregory XVI in October 1840,[10] and that part of the basilica was then re-opened. The entire building was reconsecrated in 1854 in the presence of Pope Pius IX and fifty cardinals. Many features of the building were still to be executed at that date, however, and work ultimately extended into the twentieth century. The quadriporticus looking toward the Tiber was completed by the Italian Government, which declared the church a national monument. On 23 April 1891, an explosion at the gunpowder magazine at Forte Portuense destroyed the basilica's stained glass windows.

On 31 May 2005, Pope Benedict XVI ordered the basilica to come under the control of an archpriest and he named Archbishop Andrea Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo as its first archpriest.

Architecture and interior

%252C_Heilige_Pforte.jpg.webp)

The covered portico (or narthex) that precedes the façade is a Neo-classicist addition of the 19th-century reconstruction. On the right is the Holy Door, which is opened only during the Jubilees. On the inside is a second door, known as the Byzantine door, which was present in the pre-19th century basilica; it contains on one side 56 small square engraved bronze panels, and was commissioned in 1070 by Pantaleone, Consul of Amalfi in Constantinople, and putatively cast in Constantinople. It depicts a number of episodes in the life of Christ and the apostles.

The new basilica has maintained the original structure with one nave and four side aisles. It is 131.66 metres (432.0 ft) long, 65 metres (213 ft)-wide, and 29.70 metres (97.4 ft)-high, the second largest in Rome.

The nave's 80 columns and its wood and stucco-decorated ceiling are from the 19th century. All that remains of the ancient basilica are the interior portion of the apse with the triumphal arch. The mosaics of the apse were greatly damaged in the 1823 fire; only a few traces were incorporated in the restoration. The 5th-century mosaics of the triumphal arch are original (but also heavily reworked): an inscription in the lower section attest they were done at the time of Leo I, paid by Galla Placidia. The subject portrays the Apocalypse of John, with the bust of Christ in the middle flanked by the 24 Doctors of the Church, surmounted by the flying symbols of the four Evangelists. Saint Peter and Saint Paul are portrayed at the right and left of the arch, the latter pointing downwards (probably to his tomb).

From the inside, the windows may appear to be stained glass, but they are actually translucent alabaster.[11]

The ciborium of the confession of Arnolfo di Cambio (1285) belongs to the 13th century.

In the old basilica each pope had his portrait in a painted frieze extending above the columns separating the aisles from the nave. A 19th-century mosaic version can be seen now. The nave's interior walls were also redecorated with painted scenes from Saint Paul's life placed between the windows of the clerestory.

South of the transept is the cloister, considered "one of the most beautiful of the Middle Ages".[12] Built by Vassalletto in 1205–1241, it has double columns of different shapes. Some columns have inlays with golden and colored-glass mosaics; the same decoration can be seen on the architrave and the inner frame of the cloister. Also visible are fragments from the destroyed basilica and ancient sarcophagi, one with scenes of the myth of Apollo.

Tomb of Saint Paul

_(14743552956).jpg.webp)

According to tradition, Saint Paul's body was buried two miles away from the location of his martyrdom, in the sepulchral area along the Ostiense Way, which was owned by a Christian woman named Lucina. A tropaeum was erected on it and quickly became a place of veneration.[lower-alpha 2]

Constantine I erected a basilica on the tropaeum's site, and the basilica was significantly extended by Theodosius I from 386, into what is now known as Saint Paul Outside the Walls. During the 4th century, Paul's remains, excluding the head, were moved into a sarcophagus. (According to church tradition the head rests at the Lateran.) Paul's tomb is below a marble tombstone in the basilica's crypt, at 1.37 metres (4.5 ft) below the altar. The tombstone bears the Latin inscription PAULO APOSTOLO MART ("to Paul the apostle and martyr"). The inscribed portion of the tombstone has three holes, two square and one circular.[13] The circular hole is connected to the tomb by a pipeline, reflecting the Roman custom of pouring perfumes inside the sarcophagus, or to the practice of providing the bones of the dead with libations. The sarcophagus below the tombstone measures 2.55 metres (8.4 ft) long, 1.25 metres (4.1 ft) wide and 0.97 metres (3.2 ft) high.

The discovery of the sarcophagus is mentioned in the chronicle of the Benedictine monastery attached to the basilica, in regard to the 19th century rebuilding. Unlike other sarcophagi found at that time, this was not mentioned in the excavation papers.[14]

On 6 December 2006, it was announced that Vatican archaeologists had confirmed the presence of a white marble sarcophagus beneath the altar, perhaps containing the remains of the Apostle.[15][16] A press conference held on 11 December 2006[17] gave more details of the work of excavation, which lasted from 2002 to 22 September 2006, and which had been initiated after pilgrims to the basilica expressed disappointment that the Apostle's tomb could not be visited or touched during the Jubilee year of 2000.[18] The sarcophagus was not extracted from its position, so that only one of its two longer sides is visible.[19] In 2009 the Pope announced that radiocarbon dating confirmed that the bones in the tomb date from the 1st or 2nd century suggesting that they are indeed Paul's.[20]

A curved line of bricks indicating the outline of the apse of the Constantinian basilica was discovered immediately to the west of the sarcophagus, showing that the original basilica had its entrance to the east, like Saint Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. The larger 386 basilica that replaced it had the Via Ostiense (the road to Ostia) to the east and so was extended westward, towards the river Tiber, changing the orientation diametrically.

Abbots

.JPG.webp)

The complex includes an ancient Benedictine Abbey, restored by Odo of Cluny in 936.

- 1796–1799 Giovanni Battista Gualengo

- 1799–1799 Giustino Nuzi

- 1800–1800 Giovanni B. Gualengo

- 1803–1806 Stefano Alessandri

- 1806–1810 Giuseppe Giustino di Costanzo

- 1810–1815 Stefano Alessandri

- 1815–1821 Francesco Cavalli

- 1821–1825 Adeodato Galeffi

- 1825–1831 Giovanni Francesco Zelli

- 1831–1838 Vincenzo Bini

- 1838–1844 Giovanni Francesco Zelli

- 1844–1850 Paolo Theodoli

- 1850–1853 Mariano Falcinelli-Antoniacci

- 1853–1858 Simplicio Pappalettere

- 1858–1867 Angelo Pescetelli[21]

- 1867–1895 Leopoldo Zelli Jacobuzi

- 1895–1904 Bonifacio Oslaender

- 1904–1918 Giovanni del Papa

- 1918–1929 Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster

- 1929–1955 Ildebrando Vannucci

- 1955–1964 Cesario D'Amato

- 1964–1973 Giovanni Battista Franzoni

- 1973–1980 Position empty

- 1980–1988 Giuseppe Nardin

- 1988–1996 Luca Collino

- 1996–1997 Position empty

- 1997–2005 Paolo Lunardon

- 2005–2015 Edmund Power

- 2015–2020 Roberto Dotta

- 2020-present Sede vacante; overseen by an appointed Papal Administrator, Arrigo Miglio

Archpriests

- Andrea Cardinal Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo (31 May 2005 – 3 July 2009)

- Francesco Cardinal Monterisi (3 July 2009 – 23 November 2012)

- James Michael Cardinal Harvey (23 November 2012 – )

Other burials

Gallery

Saint Paul Outside the Walls

Saint Paul Outside the Walls%252C_Innenansicht_1.jpg.webp) Interior of the church

Interior of the church

Detail of the apse mosaic: Pope Honorius III, who commissioned it.

Detail of the apse mosaic: Pope Honorius III, who commissioned it.

See also

- Bible of San Paolo fuori le Mura

- Leonine Wall, first wall around Vatican City

- List of Greco-Roman roofs

Notes

- Since Benedict XVI's renunciation of the title of "Patriarch of the West", Latin Catholic patriarchal basilicas are known as papal basilicas.

- The earliest account of a visit to the memorials of the apostles is attributed to Gaius, the Presbyter, "who lived when Zephyrinus was bishop of Rome [AD 199–217]", as quoted by Eusebius reporting that "I can point out the tropaia of the Apostles [Peter and Paul]; for if you go to the Vatican or the Ostian Way, you will find the tropaia of those who founded this Church".

References

- Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 15 (The Treaty of the Lateran by Benedict Williamson (London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne Limited, 1929), pp. 42–66 Archived 2018-05-23 at the Wayback Machine).

- Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 13 (Ibidem Archived 2018-05-23 at the Wayback Machine).

- Lateran Treaty of 1929, Article 15 (Ibidem Archived 2018-05-23 at the Wayback Machine).

- "The Basilica". Saint Paul Outside the Wall.

- O'Malley, John W. (2010). A History of the Popes. New York: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 978-1580512299.

- Margaret English Frazer (1973). "Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 27 (1973): 145–162. doi:10.2307/1291338. JSTOR 1291338.

- Rusconi, Roberto (2016). "Benedict XIV and the Holiness of the Popes in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century". In Messbarger, Rebecca; Johns, Christopher M. S.; Gavitt, Philip (eds.). Benedict XIV and the Enlightenment: Art, Science, and Spirituality. University of Toronto Press. pp. 278–279. doi:10.3138/9781442624757. ISBN 978-1442624757.

- "Church of Santo Stefano del Cacco", Turismoromam, Dipartimento Grandi Eventi, Sport, Turismo e Moda

- Terry Kirk (2005). The Architecture of Modern Italy: The Challenge of Tradition 1750–1900. p. 173. ISBN 978-1568984209.

- Holy See, Augustissimam beatissimi, (in Italian}, issued 21 December 1840, accessed 3 July 2023

- "San Paolo Fuori le Mura", Frommer's.

- Hinzen-Bohlen, p. 411.

- "The Tomb off St. Paul", Basilica Papale San Paolo Fuori le Mura.

- Gheddo, Piero (2006-09-22). "Asia News: Saint Paul's sarcophagus found". Asianews.it. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- "St. Paul's Tomb Unearthed in Rome". National Geographic News. 11 December 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "St Paul burial place confirmed". Catholic News Agency. 2006-12-06. Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Communiqué about the press conference Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Associated Press: Have St. Paul's remains been unearthed?". NBC News. 2006-12-07. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Fraser, Christian (2006-12-07). "Christian Fraser, St Paul's tomb unearthed in Rome, BBC News, 7 December 2006". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- "Pope Says Tests ‘Seem to Conclude’ Bones Are the Apostle Paul’s" New York Times (The Associated Press), June 28, 2009.

- For abbots from 1796 to 1867: Turbessi, G. "Vita monastica dell'abbazia di San Paolo nel secolo XIX." Revue Bénédictine 83 (1973): 49–118.

Further reading

- Nicola Camerlenghi, St. Paul's Outside the Walls: A Roman Basilica from Antiquity to the Modern Era (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 439–440, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 978-0870991790

- Hinze-Bohlen, Brigitte. Kunst & Architektur-ROM. Cologne: Könemann.

- Rendina, Claudio (2000). Enciclopedia di Roma. Newton & Compton. pp. 867–868.

- Marina Docci, San Paolo fuori le mura: Dalle origini alla basilica delle origini (Roma: Gangemi Editore 2006).

External links

- The Papal Basilica St Paul Outside-the-Walls, official site.

- St. Paul's Outside the Walls: A Virtual Basilica

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- St. Paul's Tomb Unearthed in Rome on National Geographic News, including a photograph of a side of the sarcophagus.

- The tombs of the apostles: Saint Paul

- Reliquary of St. Anne's forearm venerated in a side chapel

![]() Media related to Basilica di San Paolo Fuori le Mura at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Basilica di San Paolo Fuori le Mura at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Santa Maria Maggiore |

Landmarks of Rome Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls |

Succeeded by San Lorenzo fuori le mura |