Salina, Kansas

Salina /səˈlaɪnə/ is a city in and the county seat of Saline County, Kansas, United States.[1] As of the 2020 census, the population was 46,889.[4][5]

Salina, Kansas | |

|---|---|

City and County seat | |

Water tower (2013) | |

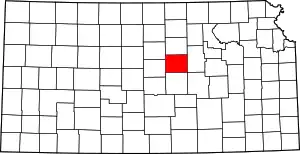

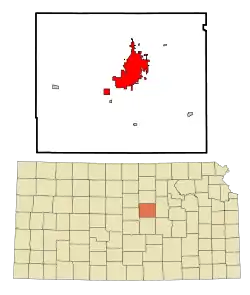

Location within Saline County and Kansas | |

KDOT map of Saline County (legend) | |

| Coordinates: 38°50′25″N 97°36′41″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Saline |

| Founded | 1858 |

| Incorporated | 1870 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Trent Davis (D)[2] |

| • City manager | Mike Schrage |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.74 sq mi (66.65 km2) |

| • Land | 25.70 sq mi (66.57 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.09 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,227 ft (374 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 46,889 |

| • Density | 1,800/sq mi (700/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 67401-67402[6] |

| Area code | 785 |

| FIPS code | 20-62700[1] |

| GNIS ID | 476808[1] |

| Website | salina-ks.gov |

In the early 1800s, the Kanza tribal land reached eastward from the middle of the Kansas Territory. In 1858, settlers from Lawrence founded the Salina Town Company with a wagon circle, under constant threat of High Plains tribal attacks from the west. It was named for the salty Saline River. Saline County was soon organized around this township, and in 1870, Salina incorporated as a city.

As the westernmost town on the Smoky Hill Trail, Salina boomed until the Civil War by establishing itself as a trading post for westbound immigrants, gold prospectors bound for Pikes Peak, and area American Indian tribes. It boomed again from the 1940s-1950s when the Smoky Hill Army Airfield was built for World War II strategic bombers.

It is now a micropolis and regional trade center for North Central Kansas. Higher education institutions include the KSU College of Technology and Aviation and Kansas Wesleyan University; and employers include Tony's Pizza, Exide Battery, Great Plains Manufacturing, and Asurion.

History

Native inhabitance: up to 1800s

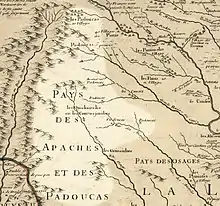

Shortly prior to European colonization of the area in the early 1700s, the site that would become Salina was located within the western territory of the Kansa people.[7] Claimed first by France as part of Louisiana and later acquired by the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, it was within the area organized by the U.S. as Kansas Territory in 1854.[8][9] The French traders who mapped the forks of les Grande Riviere des Cansez, located the western village of les Cansez at the general confluence of the Smoky Hill, Saline, and Solomon Rivers with villages of the Paducas tribe just to the west on heads of those streams.[10]

By the time of exploration of the prairie by the United States following the Louisiana Purchase in the early 1800s, the Republican Pawnee had established its influence in the Smoky Hills,[11] driving the Kansa to its northeastern Kansas settlements.[12][13][14][15]

The United States established forts throughout the territory to provide security for established commercial trade trails, including the Smoky Hill Trail and the Santa Fe Trail. The Smoky Hill Trail passed through the Salina site where the Fort Riley/Fort Larned Road split off to cross the Smoky Hill River to the southwest.

Battle of Indian Rock: 1857

By the time of the first tentative settlements by United States citizens, the site was claimed as hunting grounds by the High Plains tribes of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux, which had expanded into the area, driving out the Pawnee. However, the Kansa continued to hunt in the area, in which they were joined by the Delaware and Potawatomi tribes which had been relocated by the U.S. Government near the Kansa's reserve and assured of hunting access to the plains. The High Plains tribes were hostilely opposed to both the U.S. settlers in central Kansas and to the relocated tribes in Eastern Kansas and Nebraska, who they also regarded as settlers, and there were several raids in the Salina area in the 1850s. These Indian skirmishes repeatedly discouraged settlement of the Salina site until 1857, according to William A. Phillips who resided in Lawrence while scouting settlement locations.[16]

In that year, Big Chief of the Cheyenne led a party of the High Plains tribes. At Spring Creek, 20 miles west of what became Salina, they made a surprise attack on a hunting party of the "friendly" Eastern tribes. The hunting party retreated to Dry Creek, trapped and sending for help from another Kaw hunting party from Council Grove. Big Chief forced them to flee further to a butte in a bend of the Smoky Hill River, where they were joined by the Kaw reinforcements with rifles. Firing rifles from the cover of large sandstone boulders atop the butte, the defenders killed Big Chief on the first of five offensive charge attempts. His attacking bow and arrow force was devastated, leaving bodies strewn, and effectively ending the local raids.[16][17]

The aftermath was recalled by settler Christina Campbell, "one of the fiercest and most cruel Indian battles known to white settlers; around were strewn thousands of arrows and implements of Indian warfare. Indian Rock, besmeared with blood, showed the part it played in repelling the repeated savages' attacks. It was here that the Cheyenne made their last attack."[16]

Founding: 1858–1870

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The defeat of the aggressive High Plains tribes had enabled the safe return of attempted settlers. In April 1858, journalist and lawyer William A. Phillips from Lawrence led the founding of Salina, accompanied by settlers David Phillips, Alexander M. Campbell Sr. (husband of Christina), A.C. Spillman, and James Muir. They were all Scotch Presbyterians, and all but Muir were related. From a west riverbank dugout at what is now Riverside Park, they camped and designed the first building. It was a two-story dwelling and Campbell's store, at what is now the southwest corner of 5th St and Iron Ave near Founders Park. Constant tribal attacks required a wagon circle around the first water well one block west. The Campbells had the first surviving settler birth in the area, also named Christina.[18][16]

That month, and still predating the 1861 statehood of Kansas, they chartered the Salina Town Company with the Kansas territory legislature. During the following year, they organized the surrounding area as Saline County, and named Salina the county seat.[18][16][17] The westernmost town on the Smoky Hill Trail, Salina established itself as a trading post for westbound immigrants, gold prospectors bound for Pikes Peak, and area American Indian tribes.[18] The town's growth halted with the outbreak of the American Civil War when much of the male population left to join the Union Army.[19]

In 1862, residents fended off Indian raiders and suffered a second assault by bushwhackers.[19] In May and June 1864, the Salina Stockade was built to protect the town against further Indian raids. Union troops were garrisoned in Salina until March 1865, and some may have returned in June 1865. The building inside the stockade was remodeled and in September 1864 was opened as Salina's first public school. The school term ran until March 1865. The use of the building probably continued until at least June 1865.[20][21]

Growth returned with the soldiers after the war, and the town expanded rapidly with the arrival of the Kansas Pacific Railway in 1867. The construction of the railroad through Salina to Denver was a violation of treaty promises of Indian hunting grounds west of Salina, and Dog Soldiers began raiding the construction parties between Salina and Fort Wallace.[22] The following U.S. military action removed Indians from western Kansas by 1868.

Salina incorporated as a city in 1870.[19][23]

Growth: 1872–1950s

The cattle trade arrived in 1872, transforming Salina into a cowtown. The trade brought the city further prosperity, but also a rowdy culture that agitated local residents. The cattle trade relocated westward just two years later.[24] During the 1870s, wheat became the dominant crop in the area, steam-powered flour mills were built, and agriculture became the engine of the local economy. In 1874, Salina resident E. R. Switzer introduced alfalfa to area farmers, and its cultivation spread throughout the state. By 1880, the city had become an area industrial center with several mills, a carriage and wagon factory, and a farm implement works.[25] In 1889, the original garment factory of jeans maker Lee was opened.[26] In the following decade, three railroads were built through the city.[25] The success of the wholesale and milling industries drove Salina's growth into the early 1900s, such that it was at one point the third-largest producer in the state and the sixth-largest in the United States.[17]

In 1943, the U.S. Army established Smoky Hill Army Airfield southwest of the city. The installation served as a base for strategic bomber units throughout World War II. Renamed Smoky Hill Air Force Base in 1948, it was closed the following year and was reopened in 1951 as Schilling Air Force Base, part of the Strategic Air Command.[27] The re-opening triggered an economic boom in Salina, causing the city's population to increase by nearly two-thirds during the 1950s.[17] The U.S. Department of Defense closed the base permanently in 1965, but the city of Salina acquired it and converted it into Salina Municipal Airport and an industrial park.[27] This led to substantial industrial development, attracted firms such as Beechcraft, and made manufacturing a primary driver of the local economy.[28]

The Salina micropolitan area is a center of trade, transportation, and industry in North Central Kansas.[17]

Geography

Salina is located at 38°50′25″N 97°36′41″W (38.8402805, -97.6114237) at an elevation of 1,224 feet (373 m).[1] Located in North Central Kansas at the intersection of Interstate 70 and Interstate 135, it is 81 miles (130 km) north of Wichita, Kansas, 164 miles (264 km) west of Kansas City, Missouri, and 401 miles (645 km) east of Denver, Colorado.[29]

Salina lies in the Smoky Hills region of the Great Plains approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) west-southwest of the confluence of the Saline and Smoky Hill Rivers.[30] The Smoky Hill River runs north then northeast through the eastern part of the city; the Saline River flows southeast immediately north of the city.[31] In the northeast part of the city, the old channel of the Smoky Hill branches from the river's current course and winds west, north, and back east before draining back into the river. Mulberry Creek, a tributary of the Saline, flows northeast through the far northern part of the city. Dry Creek, a tributary of Mulberry Creek, flows north through the western part of the city.[32]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 25.15 square miles (65.14 km2), of which 25.11 square miles (65.03 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) is water.[33]

Climate

Salina lies in the transition area between North America's humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa) and humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa) zones. Consequently, summers are typically hot and humid, and winters are typically cold and dry.[34] On average, January is coldest, July is hottest, and May has the greatest precipitation.[35]

Salina is in a region prone to severe thunderstorms with damaging winds, hail, and tornadoes. On June 21, 1969, an F3 tornado struck the southern part of the city, severely damaging or destroying more than 100 homes and businesses and injuring 60 people.[36] On September 25, 1973, a second F3 tornado passed through the southeast part of town, injuring six people and destroying two houses and a trailer park.[37] On June 11, 2008, another EF3 tornado passed on the south side of the town, severely damaging several buildings.[38]

The annual average temperature in Salina is 56.1 °F (13 °C). The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 31.0 °F (−0.6 °C) in January to 81.1 °F (27.3 °C) in July. The high temperature reaches or exceeds 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 67.6 days per year and reaches or exceeds 100 °F (38 °C) an average of 15.9 days per year. The low temperature falls below the freezing point, 32 °F (0 °C), an average of 115.5 days per year and below 0 °F (−18 °C) an average of 2.1 days per year.[39] The hottest temperature recorded in Salina is 118 °F (48 °C) on August 13, 1936; the coldest temperature recorded is −31 °F (−35 °C) on February 13, 1905.[40]

On average, Salina receives 32.2 in (818 mm) of precipitation per year with the largest share being received from May to August.[39] The average relative humidity is 64%.[41] Snowfall averages 16.6 inches (42 cm) per year.[42]

| Climate data for Salina, Kansas Salina Regional Airport (KSLN), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1900–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

84 (29) |

96 (36) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

114 (46) |

116 (47) |

118 (48) |

110 (43) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

118 (48) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.2 (18.4) |

70.9 (21.6) |

81.0 (27.2) |

87.7 (30.9) |

93.9 (34.4) |

101.1 (38.4) |

105.7 (40.9) |

103.3 (39.6) |

98.0 (36.7) |

89.7 (32.1) |

76.0 (24.4) |

64.9 (18.3) |

106.9 (41.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

46.3 (7.9) |

57.3 (14.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

76.8 (24.9) |

88.1 (31.2) |

92.8 (33.8) |

90.1 (32.3) |

81.9 (27.7) |

69.1 (20.6) |

55.1 (12.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

67.4 (19.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.8 (−0.7) |

34.9 (1.6) |

45.3 (7.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

65.1 (18.4) |

76.2 (24.6) |

80.9 (27.2) |

78.6 (25.9) |

70.1 (21.2) |

57.0 (13.9) |

43.6 (6.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

55.8 (13.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 20.1 (−6.6) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

33.2 (0.7) |

42.3 (5.7) |

53.4 (11.9) |

64.2 (17.9) |

69.1 (20.6) |

67.1 (19.5) |

58.2 (14.6) |

44.9 (7.2) |

32.1 (0.1) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

44.2 (6.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 2.2 (−16.6) |

5.6 (−14.7) |

15.4 (−9.2) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

59.0 (15.0) |

57.0 (13.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

5.8 (−14.6) |

−3.0 (−19.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −28 (−33) |

−31 (−35) |

−11 (−24) |

5 (−15) |

19 (−7) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

38 (3) |

28 (−2) |

13 (−11) |

−5 (−21) |

−24 (−31) |

−31 (−35) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.71 (18) |

0.87 (22) |

1.82 (46) |

2.72 (69) |

5.04 (128) |

3.75 (95) |

3.92 (100) |

3.71 (94) |

2.65 (67) |

2.16 (55) |

1.22 (31) |

1.12 (28) |

29.69 (753) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.0 (15) |

3.2 (8.1) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

1.2 (3.0) |

3.3 (8.4) |

16.6 (41.86) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.0 | 5.1 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 88.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 9.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 63 | 67 | 65 | 71 | 62 | 59 | 61 | 50 | 56 | 66 | 73 | 64 |

| Source 1: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[39][42] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[40][43] Weatherbase: Humidity[41] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 918 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,111 | 238.9% | |

| 1890 | 6,149 | 97.7% | |

| 1900 | 6,074 | −1.2% | |

| 1910 | 9,688 | 59.5% | |

| 1920 | 15,085 | 55.7% | |

| 1930 | 20,155 | 33.6% | |

| 1940 | 21,073 | 4.6% | |

| 1950 | 26,176 | 24.2% | |

| 1960 | 43,202 | 65.0% | |

| 1970 | 37,714 | −12.7% | |

| 1980 | 41,843 | 10.9% | |

| 1990 | 42,303 | 1.1% | |

| 2000 | 45,679 | 8.0% | |

| 2010 | 47,707 | 4.4% | |

| 2020 | 46,889 | −1.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[44] 2010-2020[5] | |||

Salina is the anchor city of the Salina Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Saline and Ottawa counties.[45]

2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 47,707 people, 19,391 households, and 12,024 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,092.4 inhabitants per square mile (807.9/km2). There were 20,803 housing units at an average density of 916.4 per square mile (353.8/km2). The racial makeup was 86.2% White, 3.7% African American, 2.3% Asian, 0.5% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 3.8% from some other race, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 10.7% of the population.[46]

There were 19,391 households, of which 31.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.3% were married couples living together, 4.9% had a male householder with no wife present, 11.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.0% were non-families. 31.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39, and the average family size was 2.99.[46]

The population was spread out, with 25.1% of residents under the age of 18; 9.9% between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.4% from 25 to 44; 25.3% from 45 to 64; and 14.3% 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.4 years. The gender makeup was 49.4% male and 50.6% female.[46]

The median income for a household was $42,027, and the median income for a family was $54,491. Males had a median income of $39,143 versus $28,145 for females. The per capita income was $23,253. About 9.3% of families and 13.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.1% of those under age 18 and 7.3% of those age 65 or over.[46]

2000 census

As of the census[47] of 2000, there were 45,679 people, 18,523 households, and 11,873 families. The population density was 2,009.6 inhabitants per square mile (775.9/km2). There were 19,599 housing units at an average density of 862.2 per square mile (332.9/km2). The racial makeup was 87.76% White, 3.57% Black or African American, 0.56% Native American, 1.96% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 3.78% from other races, and 2.32% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.71% of the population.[47]

There were 18,523 households, of which 31.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.8% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.9% were non-families. 30.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 2.98.

The population was spread out, with 25.9% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 28.7% from 25 to 44, 21.1% from 45 to 64, and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.8 males.

The median income for a household was $36,066, and the median income for a family was $45,433. Males had a median income of $31,250 versus $21,944 for females. The per capita income was $18,593. About 6.7% of families and 9.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.6% of those under age 18 and 9.2% of those age 65 or over.[46]

Economy

Salina hosted the first garment factory for Lee Jeans, which opened in 1889.[26]

Manufacturing, education, health, and social services are the predominant industries in Salina.[48] Agricultural transportation is also a major industry.[48] Major employers include these: Tony's Pizza, a Schwan Food Company brand, has operations in Salina to produce frozen pizzas and food for school cafeterias and other institutions;[49] Philips Lighting, a manufacturer of lighting;[50] Exide Battery, a storage battery manufacturer;[51] Great Plains Manufacturing, a farm equipment manufacturer;[52] ElDorado National, a commercial bus manufacturer;[53] and Asurion, an insurance provider.

As of 2010, 71.0% of the population over the age of 16 was in the labor force. 0.4% was in the armed forces, and 70.6% was in the civilian labor force with 66.9% being employed and 3.7% unemployed. The composition, by occupation, of the employed civilian labor force was: 27.2% in management, business, science, and arts; 25.4% in sales and office occupations; 19.4% in service occupations; 9.9% in natural resources, construction, and maintenance; 18.2% in production, transportation, and material moving. The three industries employing the largest percentages of the working civilian labor force were: educational services, health care, and social assistance (21.2%); manufacturing (17.8%); and retail trade (13.1%).[46]

The cost of living in Salina is relatively low; compared to a U.S. average of 100, the cost of living index is 80.9.[54] As of 2010, the median home value was $109,700, the median selected monthly owner cost was $1,070 for housing units with a mortgage and $396 for those without, and the median gross rent was $599.[46]

Top employers

According to Salina's 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[55] these are the city's top employers:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tony's Pizza | 2,000 |

| 2 | Salina Regional Health Center | 1,082 |

| 3 | USD 305 | 935 |

| 4 | Exide | 800 |

| 5 | Great Plains Manufacturing | 650 |

| 6 | Philips Lighting | 600 |

| 7 | City of Salina | 493 |

| 8 | Saline County | 277 |

| 9 | ElDorado National | 255 |

Government

Salina is a city of the first class with a commission-manager form of government which it adopted in 1921.[56][57] The city commission consists of five members elected at large, one of whom the commission annually selects to serve as mayor. Commission candidates who receive the most and second–most votes are elected for a four-year term; the candidate who receives the third most votes is elected for a two-year term.[57] The commission sets policy and appoints the city manager, who serves as the chief executive, responsible for administering the city government and appointing all city employees.[58]

The Salina Fire department operates four stations inside the city.

Salina is the county seat of Saline County. The county courthouse is located downtown, and all departments of the county government base their operations in the city.[59]

Salina lies within Kansas's 1st U.S. Congressional District. For the purposes of representation in the Kansas Legislature, the city is located in the 24th district of the Kansas Senate and the 69th, 71st, and 108th districts of the Kansas House of Representatives.[56]

Education

Primary and secondary education

Salina USD 305 public school district operates twelve schools in Salina:[54][60][61][62][63]

- Salina High School Central (9-12)

- Salina High School South (9-12)

- Lakewood Middle School (6-8)

- Salina South Middle School (6-8)

- Coronado Elementary School (K-5)

- Cottonwood Elementary School (K-5)

- Grace E. Stewart Elementary School (K-5)

- Heusner Elementary School (K-5)

- Meadowlark Ridge Elementary School (K-5)

- Oakdale Elementary School (K-5)

- Schilling Elementary School (K-5)

- Sunset Elementary School (K-5)

These are the private schools:[54]

- St. Mary's Grade School (PreK-6), Catholic school

- Salina Christian Academy (PreK-10), closed in 2019[64]

- Sacred Heart Junior-Senior High School (7-12), Catholic school

- St. John's Military School (6-12), male only, closed in 2019[65]

- Cornerstone Classical School (PreK-12)

Colleges and universities

- Kansas State University Polytechnic Campus

- Kansas Wesleyan University

- Marymount College (closed in 1989)

- Salina Area Technical College

- Salina Normal University (closed in 1904)[66]

- University of Kansas School of Medicine, Salina

Infrastructure

Transportation

Interstate 70 and U.S. Route 40 run concurrently east-west north of Salina. Interstate 135 and U.S. Route 81 run concurrently north-south along the west side of the city. The I-70/I-135 interchange northwest of the city is the northern terminus of I-135.[67] K-140, which approaches Salina from the southwest, formally ends at its interchange with I-135 before entering the city as State Street. North of Salina, the city's main north-south thoroughfare, Ninth Street, becomes K-143 at its interchange with I-70.[32]

CityGo is the local public transport bus service, operating five routes in the city (yellow, blue, red, purple and green). CityGo also provides intercity paratransit bus service to surrounding communities.[68] Greyhound Lines provides bus service westward towards Denver, Colorado and eastward toward Kansas City, Missouri.[69] Bus service is provided daily southward towards Wichita, Kansas by BeeLine Express (subcontractor of Greyhound Lines).[69][70]

Salina Municipal Airport is located southwest of the city.[71] Used primarily for general aviation, it hosts one commercial airline United Express with flights to Chicago O'Hare and Denver International Airport.

Union Pacific Railroad operates one freight rail line through Salina. Its Kansas Pacific (KP) Line runs northeast-southwest through the northern part of the city.[32][72] Salina is also the southeastern terminus for both the Kyle Railroad and the Kansas and Oklahoma Railroad.[73]

Utilities

The city government's Department of Public Works is responsible for water treatment and distribution, waste water removal, sewer maintenance, and trash collection. Westar Energy provides electric power.[74] Residents primarily use natural gas for heating fuel; natural gas service is provided by Kansas Gas Service.[54][74]

Media

The Salina Journal is the local newspaper, published daily.[77]

Salina is a center of broadcast media for North Central Kansas. Three AM and 13 FM radio stations are licensed to or broadcast from the city.[78] Salina is in the Wichita-Hutchinson television market, and five television stations broadcast from the city.[79][80] These include two independent stations as well as ABC, Fox, and NBC affiliates which are satellites of their respective affiliates in Wichita.[81][82] Salina is also home to the only Public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable TV channels in the state. Cox Communications is the main cable system serving the city, and customers can see local programming and create their own programming to be shown on channels 20 and 21.

Culture

Events

The city holds several community events throughout the year.[83] Each June, the Salina Arts & Humanities department holds the Smoky Hill River Festival. Held in Oakdale Park and lasting three and a half days, the Festival includes arts and crafts shows, music concerts, games, and other activities.[84] Originally held as a downtown street parade in 1976 to celebrate the United States Bicentennial, the festival proved popular enough for the city to hold it every year.[85] To celebrate Independence Day, the city puts on its All American Fourth and Play Day in the Park which includes children’s games, music, and dance performances in Oakdale Park.[86] The Smoky Hill Museum Street Fair takes place in September and includes a parade, a chili cook-off, and historic demonstrations.[87] In November, downtown Salina hosts the city’s Christmas festival which includes a 5k run, a mile walk, live music, dance performances, children’s entertainment and the Parade of Lights, a parade of floats decorated with Christmas lights.[88]

The city's private organizations host several annual expos, fairs, trade shows, and various other events. Several of these pertain to area agriculture including the Chamber of Commerce’s Mid-America Farm Expo in March, the Discover Salina Naturally Festival in May, the 4-H Tri-Rivers Fair and Rodeo in August, and The Land Institute’s Prairie Festival in September. Other annual events held in the city include the Home Builders Associations of Salina’s Home and Leisure Show in February, the ISIS Shrine Circus and Saline County Mounted Patrol Rodeo in April, the Smoky Hill Sportsman Expo in August, Blue Heaven Studios’ Blues Masters at the Crossroads festival in October, and the Prairie Longrifles Wild West Trade Show in December as well as several car shows and high school sports events.[83][89]

Points of interest

Operated by the city government's Arts & Humanities department, the Smoky Hill Museum contains artifacts, exhibits, and public educational programs on local history, agriculture, and education with collections dating back to 1879..[90]

The Tony's Pizza Events Center (formerly Bicentennial Center) is the primary venue in the city for large indoor events. It includes a 7,500-seat multipurpose arena and the 18,000 sq ft (1,700 m2) Heritage Hall convention center. The Center hosts concerts, sporting events, and trade shows.[91]

The Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure is a public zoo and wildlife park located 6 miles (9.7 km) west of the city near Hedville.[92] It has animal exhibits, an art gallery, and a wildlife museum.[93]

Indian Rock Park is the tallest point in the area, mainly featuring a hill within the vast Wellington Formation stretching to Oklahoma. In the late 1950s, part of the hill was excavated for flood control, diverting the Smoky Hill River along the edge of the park and creating 80-foot steep shale bluffs. It has a panoramic view of the city, a river fishing pier, a pond from the former brick factory, and hiking trails.[16]

Salina Community Theatre (SCT) is a regionally acclaimed theater, producing seven seasonal shows and three summer shows every year. Productions include the contemporary, such as ABBA's Mamma Mia! and Disney's Newsies, and classics such as Miracle on 34th Street.[94]

Religion

More than 70 Christian churches are in and around Salina[95][96] including the cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Salina (Sacred Heart Cathedral) and the cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Kansas (Christ Cathedral).[97][98] The Roman Catholic Diocese has its regional administrative offices in Salina[99] as do the Presbytery of Northern Kansas[100] and the Salina District of the United Methodist Church which is based at Kansas Wesleyan University.[101]

Sports

- Salina was home to minor league baseball from 1898–1952. The Salina Blue Jays and other Salina teams played as a member of the Kansas State League (1898), Central Kansas League (1908–1910, 1912), Kansas State League (1913–1914), Southwestern League (1922–1926) and Western Association (1938–1941, 1946–1952). Salina was an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians (1941) and Philadelphia Phillies (1946–1952). Salina teams played at Athletic Park (1898–1914), Oakdale Park (1922–1926) and Kenwood Field (1938–1952).[103][104][105][106]

- Salina hosted the Kansas Cagerz[107] and Salina Rattlers[108] basketball teams.

- Salina hosted the National Junior College Athletic Association Division I women's basketball national tournament each season in the Bicentennial Center.[109]

- Salina hosted the Women's Big Eight basketball tournament at the Bicentennial Center. When the Big Eight became the Big 12, the tournament was moved to Kansas City, Missouri.

- Salina hosts the Kansas State High School Activities Association (KSHSAA) Class 4A state wrestling tournament as well as the Class 3A & 4A volleyball tournaments, the Class 4A state basketball tournament, and the Class 4A state softball tournament. Salina also occasionally hosts the Class 4A state baseball tournament and one of the state championship football games.

- Salina was home to the Salina Bombers, an indoor football team playing in the Champions Professional Indoor Football League from 2013 to 2014, then Champions Indoor Football.

- Salina hosts the Salina Liberty, the second indoor football team from the city, who now play in the CIF.

- Salina is the home of the Kansas Wesleyan University Coyotes, a 20-sport National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics athletics program. The Coyotes have been a member of the Kansas Collegiate Athletic Conference since 1928.

In popular culture

- The 1980 teen comedy film Up the Academy starring Ralph Macchio was filmed entirely in Salina, mostly on the campus of St. John's Military School.[110]

- Scenes in the 1955 movie Picnic, starring William Holden and Kim Novak, were filmed in Salina: the train arrival and The Bensons' mansion.

- Millie Dillmount, the fictional main character in the musical Thoroughly Modern Millie, is from Salina. She leaves home for New York City, determined never to return, as depicted in the opening number, "Not for the Life of Me."

- In Alfred Hitchcock's film Vertigo, the character Judy Barton (played by Kim Novak) comes from 425 Maple Avenue in Salina.

- The Avett Brothers wrote a song titled "Salina" on the 2007 album Emotionalism.

- The song "Wichita Skyline" by Americana pop singer Shawn Colvin, off of her hit 1996 album A Few Small Repairs, mentions the city of Salina, but Colvin mispronounces it as "Sa-LEE-na".[111]

Notable people

Notable individuals who were born in or have lived in Salina include former White House press secretary Marlin Fitzwater, dancer and war correspondent Betty Knox of the variety act Wilson, Keppel and Betty,[112] astronaut Steven Hawley,[113] former Governors of Kansas John W. Carlin[114] and Bill Graves,[113] radio broadcaster Paul Harvey,[115] inventor of Lee Jeans Harry Lee, and US Women's National Soccer Team goalkeeper Adrianna Franch.[116]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Saline County, Kansas

- Christ Cathedral

- Fox-Watson Theater Building

- Masonic Temple

- Whiteford (Price) Archeological Site - former site of Native American village around 1000-1350 AD

References

- "Salina, Kansas", Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior

- "City of Salina Mayors". City of Salina. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Profile of Salina, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- "QuickFacts; Salina, Kansas; Population, Census, 2020 & 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". United States Postal Service. 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- Sturtevant, William C. (1967). "Early Indian Tribes, Culture Areas, and Linguistic Stocks [Map]". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- "Louisiana Purchase". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. August 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- "Kansas Territory". Kansapedia. March 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- Delisle, Guillaume (1718), 1718 Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississipi

- Pike, Zebulon (1895). Coues, Elliott (ed.). The Expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike: Arkansaw Journey. Mexican Tour. New York, NY: Francis P. Harper. pp. 417–652.

Were overtaken by the Pawnee chief whose party we left the day before, who informed us the hunting-party had taken another road, and that he had come to bid us goodbye.

"From Pawnee Village through Kansas ... " Zebulan Pike recorded the Pawnee's control of the Smoky Hills through to the Great Bend of the Arkansas River. - Frémont, J. C. 1934. The expeditions of John Charles Frémont. (D. Jackson and M. L. Spence, Eds.). University of Illinois Press, Chicago. Fremont observed Pawnee desolation of Kaw villages "After crossing this stream, I rode off some miles to the left, attracted by the appearance of a cluster of huts near the mouth of the [Little] Vermillion. It was a large but deserted Kansas village, scattered in an open wood along the margin of the stream, on a spot chosen with the customary Indian fondness for beauty and scenery. The Pawnees had attacked it in the early spring [of 1843]. Some of the houses were burnt, and others blackened with smoke, and weeds were already getting possession of the cleared places."

- Howard C. Raynesford (1953). "The Raynesford Papers: Notes- The Smoky Hill River & Fremont's Indian Village". Archived from the original on January 23, 2003. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- 19th Century Kansas Trails (PDF), Kansas Department of Transportation, retrieved December 4, 2021

- Carson Bear (April 4, 2018). "A Nearly Pristine Pawnee Tipi Ring Site Preserved for More Than a Century". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- Lichti, Carol (February 25, 1996). "On Hallowed Ground : Story of Indian Rock and Lakewood". The Salina Journal. Salina, Kansas. p. 47. Retrieved December 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

As news of the battle spread, the potential for settlement lured Phillips, who was in Lawrence, to return to the area where Salina would be founded.

- "Salina History". City of Salina, Kansas. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- "History". City of Salina. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- Blackmar, Frank W., ed. (1912). "Salina". Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. Vol. 2. Chicago: Standard. pp. 634–635.

- Bramwell, Ruby P. (1969). City on the Move: The Story of Salina. Salina: Survey Press. p. 61.

- Morrison, pp. 3-4.

- Collins. Kansas Pacific. p. 13.

[After Fort Hays, it] would then enter the country of three nomadic Indian tribes: the Cheyenne, Arapahoe and Kiowa. ... mile and a half per day. ... Then the Indian raids began.

- Blackmar, Frank W., ed. (1912). "Saline County". Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. Vol. 2. Chicago: Standard. pp. 635–639.

- Cutler, William G. (1883), "Salina, Part 1", History of the State of Kansas, Chicago: A.T. Andreas

- WPA (1949). Kansas: A Guide to the Sunflower State. New York City: Hastings House. p. 273.

- "Lee Jeans History". lee.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- "SAC Bases: Smokey Hill / Schilling AFB". Strategic-Air-Command.com. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- "Narrative". Salina Area Chamber of Commerce. 2008. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- "City Distance Tool". Geobytes. Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- "Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculator". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 7, 2010. Used Latitude/Longitude of river confluence from United States Geological Survey and the latitude/longitude given on this page for Salina to calculate distance.

- "General Highway Map - Saline County, Kansas" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. October 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- "City of Salina [Map]" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. August 1, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., and McMahon, T. A.: Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1633-1644, doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007, 2007.

- "Average Weather for Salina, KS". The Weather Channel. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680-1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. p. 1105. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- Barbara Phillips (September 27, 1973). "Tornadoes take heavy Kansas toll". Salina Journal. p. 2.

- Lawson, Rob (June 12, 2008). "June 11th, EF-3 Tornado and Extremely Large Hail Slam Central Kansas". Wichita National Weather Service News Archives. National Weather Service Wichita KS. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Salina MUNI AP, KS (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS WIchita". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Salina, Kansas Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Salina Municipal Airport, KS (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- National Weather Service. "Monthly Summarized Data 1981-2010". NOWData. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- "Updates to Statistical Areas; Office of Management and Budget" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. November 20, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2009 – via National Archives.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Saline County Emergency Management (February 2009). "It Can Happen Here". A Study of the Hazards affecting Saline County, Kansas and their effects on the Community. Saline county Emergency Management. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- The Schwan Food Company (2007). "Communities of Operation". theschwanfoodcompany.com. The Schwan Food Company. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- Phillips Lighting (June 2009). "An energy saving solution for government facilities..." (PDF). Phillips Lighting. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- Exide Technologies. "Exide's Worldwide Facilities". exide.com. Exide Technologies. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Great Plains Manufacturing. "Great Plains Contact Information". greatplainsmfg.com. Great Plains Manufacturing. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- Web Creations and Consulting (2006). "About the Company". enconline.com. ElDorado National. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "Salina, Kansas". City-Data.com. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- "COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT OF CITY OF SALINA, KANSAS" (PDF). State of Kansas. December 31, 2014.

- "Salina". Directory of Kansas Public Officials. The League of Kansas Municipalities. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- "City Commission". City of Salina, Kansas. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- "City Government". City of Salina, Kansas. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- "Saline County–Official County Government Website". Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- "Salina USD 305 School Websites and Handbooks". Salina USD 305. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- "Salina Public Schools / Overview". Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- Kansas School District Boundary Map Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Saline County School District Map". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- "Welcome". Salina Christian Academy. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- "About St. John's Military School". St. John's Military School. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Mathews, Erin (April 16, 2009). "Saving Lives & Property: A Fire Department Grows Up". Salina Journal. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- "2011-2012 state transportation map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- "OCCK Transportation Services". OCCK Inc. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Greyhound". Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- info@beeline-express.com, beeline-express. "Beeline Express". Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for SLN PDF, effective September 23, 2010

- "UPRR Common Line Names" (PDF). Union Pacific Railroad. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- "Kansas & Oklahoma Railroad - Detailed Map". Watco, Inc. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- "Guide to City Services – M–Z". City of Salina, Kansas. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "Salina Regional Health Center – Stats & Services". U.S. News Best Hospitals. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "Salina Surgical Hospital - Stats & Services". U.S. News Best Hospitals. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- "Record Details – Salina Journal". Kansas Press Association. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- "Radio Stations in Salina, Kansas". Radio-Locator. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- "TV Market Maps – Kansas". EchoStar Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "TVQ TV Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- "Stations for Hays, Kansas". RabbitEars. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- "Contact Us". KSAS-TV. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- "Primary Annual Events". Salina Visitors Guide. Salina Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Smoky Hill River Festival". Salina Arts & Humanities. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Smoky Hill River Festival – History". Riverfestival.com. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- "All American Fourth/Play Day in the Park". Salina Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Street Fair". Smoky Hill Museum. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Christmas Festival & Parade of Lights". Salina Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Community Calendar". Salina Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "About Us". Smoky Hill Museum. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "General Information for the Arena". Salina Bicentennial Center. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "Rolling Hills Zoo". Google Maps. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "About Us". Rolling Hills Zoo. Archived from the original on November 27, 2005. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- "MainStage Past Seasons".

- "Find a Church in Salina, KS". Patheos. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "Churches in Salina by Denomination". Churchangel.com. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- "Parish". Sacred Heart Cathedral. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "About". Christ Cathedral. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "History". Roman Catholic Diocese of Salina. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Contact". Presbytery of Northern Kansas. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Salina District". Great Plains United Methodists. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- Fiedler, Gordon Jr. (November 20, 2011). "Buddhist monks find calling in Kansas temple". Topeka Capital Journal. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- "Salina Blues Statistics and Roster on StatsCrew.com". www.statscrew.com.

- "Welcome to the City of Salina, Kansas - Oakdale Park". www.salina-ks.gov.

- "Kenwood Field in Salina, KS history and teams on StatsCrew.com". www.statscrew.com.

- "Athletic Park in Salina, KS history and teams on StatsCrew.com". www.statscrew.com.

- Davidson, Bob (January 9, 2007). "USBL decides to take a breather for '08 - USBL quits". The Salina Journal. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- "IBA Closes Its Doors". The Salina Journal. August 17, 2001. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- "Juco women's tournament to stay in Salina through at least 2015". The Salina Journal. March 31, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- "Up the Academy". June 6, 1980. Retrieved August 22, 2016 – via IMDb.

- Shawn Colvin – Wichita Skyline, retrieved June 27, 2019

- Luke McKernan (2007). "The Wilson, Keppel and Betty Story" (PDF).

- "Hall of Fame". Salina Central High School. November 5, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- "John W. Carlin". Kansas Memory. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- Salina Journal staff (January 9, 2012). "A look back". The Salina Journal. Neighbors section, page 5.

Most of the talks were nostalgic remembrances of Salina of the 1930s when Paul Harvey worked for a local radio station.

- "Adrianna Franch - 2012 - Women's Soccer". Oklahoma State University Athletics. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

Further reading

- Salina: 1858–2008 (Images of America); Salina History Book Committee; Arcadia Publishing; 2008; ISBN 0-7385-6181-9

- Salina: Mart of the Middle West; Salina Commercial Club, Padgett's Printing House; 1908. (Various formats eBook)

- Illustrated Salina: The Forest City; Frederick A. Loomis, S. E. Rankin Publisher, 1892. (Various formats eBook)