Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol[lower-alpha 1] gcYC (11 May 1904 – 23 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí (/ˈdɑːli, dɑːˈliː/ DAH-lee, dah-LEE,[1] Catalan: [səlβəˈðo ðəˈli], Spanish: [salβaˈðoɾ ðaˈli]),[lower-alpha 2] was a Spanish surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarre images in his work.

Salvador Dalí, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol | |

|---|---|

Dalí in 1939 | |

| Born | Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech 11 May 1904 |

| Died | 23 January 1989 (aged 84) Figueres, Catalonia, Spain |

| Resting place | Crypt at Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres |

| Education | San Fernando School of Fine Arts, Madrid, Spain |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, writing, film, and jewelry |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Cubism, Dada, Surrealism |

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

Born in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, Dalí received his formal education in fine arts in Madrid. Influenced by Impressionism and the Renaissance masters from a young age he became increasingly attracted to Cubism and avant-garde movements.[2] He moved closer to Surrealism in the late 1920s and joined the Surrealist group in 1929, soon becoming one of its leading exponents. His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in August 1931, and is one of the most famous Surrealist paintings. Dalí lived in France throughout the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939) before leaving for the United States in 1940 where he achieved commercial success. He returned to Spain in 1948 where he announced his return to the Catholic faith and developed his "nuclear mysticism" style, based on his interest in classicism, mysticism, and recent scientific developments.[3]

Dalí's artistic repertoire included painting, graphic arts, film, sculpture, design and photography, at times in collaboration with other artists. He also wrote fiction, poetry, autobiography, essays and criticism. Major themes in his work include dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, religion, science and his closest personal relationships. To the dismay of those who held his work in high regard, and to the irritation of his critics, his eccentric and ostentatious public behavior often drew more attention than his artwork.[4][5] His public support for the Francoist regime, his commercial activities and the quality and authenticity of some of his late works have also been controversial.[6] His life and work were an important influence on other Surrealists, pop art and contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst.[7][8]

There are two major museums devoted to Salvador Dalí's work: the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain, and the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Biography

Early life

.jpg.webp)

Salvador Dalí was born on 11 May 1904, at 8:45 am,[9] on the first floor of Carrer Monturiol, 20 in the town of Figueres, in the Empordà region, close to the French border in Catalonia, Spain.[10] Dalí's older brother, who had also been named Salvador (born 12 October 1901), had died of gastroenteritis nine months earlier, on 1 August 1903. His father, Salvador Luca Rafael Aniceto Dalí Cusí (1872–1950)[11] was a middle-class lawyer and notary,[12] an anti-clerical atheist and Catalan federalist, whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domènech Ferrés (1874–1921),[13] who encouraged her son's artistic endeavors.[14] In the summer of 1912, the family moved to the top floor of Carrer Monturiol 24 (presently 10).[15][16] Dalí later attributed his "love of everything that is gilded and excessive, my passion for luxury and my love of oriental clothes"[17] to an "Arab lineage", claiming that his ancestors were descendants of the Moors.[5][18]

Dalí was haunted by the idea of his dead brother throughout his life, mythologizing him in his writings and art. Dalí said of him, "[we] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections."[19] He "was probably the first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute".[19] Images of his brother would reappear in his later works, including Portrait of My Dead Brother (1963).[20]

Dalí also had a sister, Ana María, who was three years younger.[12] and whom Dalí painted 12 times between 1923 and 1926.[21]

His childhood friends included future FC Barcelona footballers Emili Sagi-Barba and Josep Samitier. During holidays at the Catalan resort town of Cadaqués, the trio played football together.[22]

Dalí attended the Municipal Drawing School at Figueres in 1916 and also discovered modern painting on a summer vacation trip to Cadaqués with the family of Ramon Pichot, a local artist who made regular trips to Paris.[12] The next year, Dalí's father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in their family home. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theatre in Figueres in 1918,[23] a site he would return to decades later. In early 1921 the Pichot family introduced Dalí to Futurism. That same year, Dalí's uncle Anselm Domènech, who owned a bookshop in Barcelona, supplied him with books and magazines on Cubism and contemporary art.[24]

On 6 February 1921, Dalí's mother died of uterine cancer.[25] Dalí was 16 years old and later said his mother's death "was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her... I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul."[5][26] After the death of Dali's mother, Dalí's father married her sister. Dalí did not resent this marriage, because he had great love and respect for his aunt.[12]

Madrid, Barcelona and Paris

In 1922, Dalí moved into the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students' Residence) in Madrid[12] and studied at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts). A lean 1.72 metres (5 ft 7+3⁄4 in) tall,[27] Dalí already drew attention as an eccentric and dandy. He had long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee-breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century.[28]

At the Residencia, he became close friends with Pepín Bello, Luis Buñuel, Federico García Lorca, and others associated with the Madrid avant-garde group Ultra.[29] The friendship with Lorca had a strong element of mutual passion,[30] but Dalí said he rejected the poet's sexual advances.[31] Dalí's friendship with Lorca was to remain one of his most emotionally intense relationships until the poet's death at the hands of Nationalist forces in 1936 at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.[6]

Also in 1922, he began what would become a lifelong relationship with the Prado Museum, which he felt was, 'incontestably the best museum of old paintings in the world.'[32] Each Sunday morning, Dalí went to the Prado to study the works of the great masters. 'This was the start of a monk-like period for me, devoted entirely to solitary work: visits to the Prado, where, pencil in hand, I analyzed all of the great masterpieces, studio work, models, research.'[33]

Those paintings by Dalí in which he experimented with Cubism earned him the most attention from his fellow students, since there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time.[34] Cabaret Scene (1922) is a typical example of such work. Through his association with members of the Ultra group, Dalí became more acquainted with avant-garde movements, including Dada and Futurism. One of his earliest works to show a strong Futurist and Cubist influence was the watercolor Night-Walking Dreams (1922).[35] At this time, Dalí also read Freud and Lautréamont who were to have a profound influence on his work.[36]

In May 1925 Dalí exhibited eleven works in a group exhibition held by the newly formed Sociedad Ibérica de Artistas in Madrid. Seven of the works were in his Cubist mode and four in a more realist style. Several leading critics praised his work.[37] Dalí held his first solo exhibition at Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona, from 14 to 27 November 1925.[38][39] This exhibition, before his exposure to Surrealism, included twenty-two works and was a critical and commercial success.[40]

In April 1926 Dalí made his first trip to Paris where he met Pablo Picasso, whom he revered.[5] Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dalí from Joan Miró, a fellow Catalan who later introduced him to many Surrealist friends.[5] As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dalí made some works strongly influenced by Picasso and Miró.[41] Dalí was also influenced by the work of Yves Tanguy, and he later allegedly told Tanguy's niece, "I pinched everything from your uncle Yves."[42]

Dalí left the Royal Academy in 1926, shortly before his final exams.[5] His mastery of painting skills at that time was evidenced by his realistic The Basket of Bread, painted in 1926.[43]

Later that year he exhibited again at Galeries Dalmau, from 31 December 1926 to 14 January 1927, with the support of the art critic Sebastià Gasch.[44][45] The show included twenty-three paintings and seven drawings, with the "Cubist" works displayed in a separate section from the "objective" works. The critical response was generally positive with Composition with Three Figures (Neo-Cubist Academy) singled out for particular attention.[46]

From 1927 Dalí's work became increasingly influenced by Surrealism. Two of these works, Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1927) and Gadget and Hand (1927), were shown at the annual Autumn Salon (Saló de tardor) in Barcelona in October 1927. Dalí described the earlier of these works, Honey is Sweeter than Blood, as "equidistant between Cubism and Surrealism".[47] The works featured many elements that were to become characteristic of his Surrealist period including dreamlike images, precise draftsmanship, idiosyncratic iconography (such as rotting donkeys and dismembered bodies), and lighting and landscapes strongly evocative of his native Catalonia. The works provoked bemusement among the public and debate among critics about whether Dalí had become a Surrealist.[48]

Influenced by his reading of Freud, Dalí increasingly introduced suggestive sexual imagery and symbolism into his work. He submitted Dialogue on the Beach (Unsatisfied Desires) (1928) to the Barcelona Autumn Salon for 1928 but the work was rejected because "it was not fit to be exhibited in any gallery habitually visited by the numerous public little prepared for certain surprises."[49] The resulting scandal was widely covered in the Barcelona press and prompted a popular Madrid illustrated weekly to publish an interview with Dalí.[50]

Some trends in Dalí's work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s. Dalí was influenced by many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic, to the most cutting-edge avant-garde.[51] His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbarán, Vermeer and Velázquez.[52] Exhibitions of his works attracted much attention and a mixture of praise and puzzled debate from critics who noted an apparent inconsistency in his work by the use of both traditional and modern techniques and motifs between works and within individual works.[53]

In the mid-1920s Dalí grew a neatly trimmed mustache. In later decades he cultivated a more flamboyant one in the manner of 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez, and this mustache became a well known Dalí icon.[54]

1929 to World War II

In 1929, Dalí collaborated with Surrealist film director Luis Buñuel on the short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). His main contribution was to help Buñuel write the script for the film. Dalí later claimed to have also played a significant role in the filming of the project, but this is not substantiated by contemporary accounts.[55] In August 1929, Dalí met his lifelong muse and future wife Gala,[56] born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. She was a Russian immigrant ten years his senior, who at that time was married to Surrealist poet Paul Éluard.[57]

In works such as The First Days of Spring, The Great Masturbator and The Lugubrious Game Dalí continued his exploration of the themes of sexual anxiety and unconscious desires.[58] Dalí's first Paris exhibition was at the recently opened Goemans Gallery in November 1929 and featured eleven works. In his preface to the catalog, André Breton described Dalí's new work as "the most hallucinatory that has been produced up to now".[59] The exhibition was a commercial success but the critical response was divided.[59] In the same year, Dalí officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. The Surrealists hailed what Dalí was later to call his paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.[12][14]

Meanwhile, Dalí's relationship with his father was close to rupture. Don Salvador Dalí y Cusi strongly disapproved of his son's romance with Gala and saw his connection to the Surrealists as a bad influence on his morals. The final straw was when Don Salvador read in a Barcelona newspaper that his son had recently exhibited in Paris a drawing of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ, with a provocative inscription: "Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother's portrait".[5][18] Outraged, Don Salvador demanded that his son recant publicly. Dalí refused, perhaps out of fear of expulsion from the Surrealist group, and was violently thrown out of his paternal home on 28 December 1929. His father told him that he would be disinherited and that he should never set foot in Cadaqués again. The following summer, Dalí and Gala rented a small fisherman's cabin in a nearby bay at Port Lligat. He soon bought the cabin, and over the years enlarged it by buying neighboring ones, gradually building his beloved villa by the sea. Dalí's father would eventually relent and come to accept his son's companion.[60]

In 1931, Dalí painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory,[61] which developed a surrealistic image of soft, melting pocket watches. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and other limp watches shown being devoured by ants.[62]

Dalí had two important exhibitions at the Pierre Colle Gallery in Paris in June 1931 and May–June 1932. The earlier exhibition included sixteen paintings of which The Persistence of Memory attracted the most attention. Some of the notable features of the exhibitions were the proliferation of images and references to Dalí's muse Gala and the inclusion of Surrealist Objects such as Hypnagogic Clock and Clock Based on the Decomposition of Bodies.[63] Dalí's last, and largest, the exhibition at the Pierre Colle Gallery was held in June 1933 and included twenty-two paintings, ten drawings, and two objects. One critic noted Dalí's precise draftsmanship and attention to detail, describing him as a "paranoiac of geometrical temperament".[64] Dalí's first New York exhibition was held at Julien Levy's gallery in November–December 1933. The exhibition featured twenty-six works and was a commercial and critical success. The New Yorker critic praised the precision and lack of sentimentality in the works, calling them "frozen nightmares".[65]

Dalí and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were civilly married on 30 January 1934 in Paris.[66] They later remarried in a Church ceremony on 8 August 1958 at Sant Martí Vell.[67] In addition to inspiring many artworks throughout her life, Gala would act as Dalí's business manager, supporting their extravagant lifestyle while adeptly steering clear of insolvency. Gala, who herself engaged in extra-marital affairs,[68] seemed to tolerate Dalí's dalliances with younger muses, secure in her own position as his primary relationship. Dalí continued to paint her as they both aged, producing sympathetic and adoring images of her. The "tense, complex and ambiguous relationship" lasting over 50 years would later become the subject of an opera, Jo, Dalí (I, Dalí) by Catalan composer Xavier Benguerel.[69]

Dalí's first visit to the United States in November 1934 attracted widespread press coverage. His second New York exhibition was held at the Julien Levy Gallery in November–December 1934 and was again a commercial and critical success. Dalí delivered three lectures on Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and other venues during which he told his audience for the first time that "[t]he only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad."[70] The heiress Caresse Crosby, the inventor of the brassiere, organized a farewell fancy dress ball for Dalí on 18 January 1935. Dalí wore a glass case on his chest containing a brassiere and Gala dressed as a woman giving birth through her head. A Paris newspaper later claimed that the Dalís had dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper, a claim which Dalí denied.[71]

While the majority of the Surrealist group had become increasingly associated with leftist politics, Dalí maintained an ambiguous position on the subject of the proper relationship between politics and art. Leading Surrealist André Breton accused Dalí of defending the "new" and "irrational" in "the Hitler phenomenon", but Dalí quickly rejected this claim, saying, "I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention".[72] Dalí insisted that Surrealism could exist in an apolitical context and refused to explicitly denounce fascism.[73] Later in 1934, Dalí was subjected to a "trial", in which he narrowly avoided being expelled from the Surrealist group.[74] To this, Dalí retorted, "The difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist."[75][76]

In 1936, Dalí took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture, titled Fantômes paranoiacs authentiques, was delivered while wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet.[77] He had arrived carrying a billiard cue and leading a pair of Russian wolfhounds and had to have the helmet unscrewed as he gasped for breath. He commented that "I just wanted to show that I was 'plunging deeply into the human mind."[78]

Dalí's first solo London exhibition was held at the Alex, Reid, and Lefevre Gallery the same year. The show included twenty-nine paintings and eighteen drawings. The critical response was generally favorable, although the Daily Telegraph critic wrote: "These pictures from the subconscious reveal so skilled a craftsman that the artist's return to full consciousness may be awaited with interest."[79]

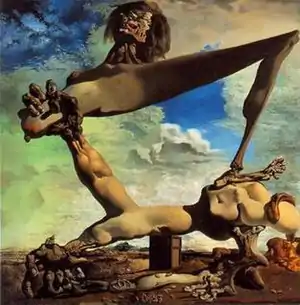

In December 1936 Dalí participated in the Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism exhibition at MoMA and a solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. Both exhibitions attracted large attendances and widespread press coverage. The painting Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936) attracted particular attention. Dalí later described it as, "a vast human body breaking out into monstrous excrescences of arms and legs tearing at one another in a delirium of auto-strangulation".[80] On 14 December, Dalí, aged 32, was featured on the cover of Time magazine.[5]

From 1933 Dalí was supported by Zodiac, a group of affluent admirers who each contributed to a monthly stipend for the painter in exchange for a painting of their choice.[81] From 1936 Dalí's main patron in London was the wealthy Edward James who would support him financially for two years. One of Dalí's most important paintings from the period of James' patronage was The Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937). They also collaborated on two of the most enduring icons of the Surrealist movement: the Lobster Telephone and the Mae West Lips Sofa.[82]

Dalí was in London when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936. When he later learned that his friend Lorca had been executed by Nationalist forces, Dalí's claimed response was to shout: "Olé!" Dalí was to include frequent references to the poet in his art and writings for the remainder of his life.[83] Nevertheless, Dalí avoided taking a public stand for or against the Republic for the duration of the conflict.[84]

In January 1938, Dalí unveiled Rainy Taxi, a three-dimensional artwork consisting of an automobile and two mannequin occupants being soaked with rain from within the taxi. The piece was first displayed at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, organized by André Breton and Paul Éluard. The Exposition was designed by artist Marcel Duchamp, who also served as host.[85][86][87]

In March that year, Dalí met Sigmund Freud thanks to Stefan Zweig. As Dalí sketched Freud's portrait, Freud whispered, "That boy looks like a fanatic." Dalí was delighted upon hearing later about this comment from his hero.[5] The following day Freud wrote to Zweig "...until now I have been inclined to regard the Surrealists, who have apparently adopted me as their patron saint, as complete fools.....That young Spaniard, with his candid fanatical eyes and his undeniable technical mastery, has changed my estimate. It would indeed be very interesting to investigate analytically how he came to create that picture [i.e. Metamorphosis of Narcissus]."[88]

In September 1938, Salvador Dalí was invited by Gabrielle Coco Chanel to her house "La Pausa" in Roquebrune on the French Riviera. There he painted numerous paintings he later exhibited at Julien Levy Gallery in New York.[89][90] This exhibition in March–April 1939 included twenty-one paintings and eleven drawings. Life reported that no exhibition in New York had been so popular since Whistler's Mother was shown in 1934.[91]

At the 1939 New York World's Fair, Dalí debuted his Dream of Venus Surrealist pavilion, located in the Amusements Area of the exposition. It featured bizarre sculptures, statues, mermaids, and live nude models in "costumes" made of fresh seafood, an event photographed by Horst P. Horst, George Platt Lynes, and Murray Korman.[92] Dalí was angered by changes to his designs, railing against mediocrities who thought that "a woman with the tail of a fish is possible; a woman with the head of a fish impossible."[93]

Soon after Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War in April 1939, Dalí wrote to Luis Buñuel denouncing socialism and Marxism and praising Catholicism and the Falange. As a result, Buñuel broke off relations with Dalí.[94]

In the May issue of the Surrealist magazine Minotaure, André Breton announced Dalí's expulsion from the Surrealist group, claiming that Dalí had espoused race war and that the over-refinement of his paranoiac-critical method was a repudiation of Surrealist automatism. This led many Surrealists to break off relations with Dalí.[95] In 1949 Breton coined the derogatory nickname "Avida Dollars" (avid for dollars), an anagram for "Salvador Dalí".[96] This was a derisive reference to the increasing commercialization of Dalí's work, and the perception that Dalí sought self-aggrandizement through fame and fortune.

World War II

The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 saw the Dalís in France. Following the German invasion, they were able to escape because on 20 June 1940 they were issued visas by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France. They crossed into Portugal and subsequently sailed on the Excambion from Lisbon to New York in August 1940.[97] Dalí and Gala were to live in the United States for eight years, splitting their time between New York and the Monterey Peninsula, California.[98][99]

Dalí spent the winter of 1940–41 at Hampton Manor, the residence of Caresse Crosby, in Caroline County, Virginia, where he worked on various projects including his autobiography and paintings for his upcoming exhibition.[100][101]

Dalí announced the death of the Surrealist movement and the return of classicism in his exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in April–May 1941. The exhibition included nineteen paintings (among them Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire and The Face of War) and other works. In his catalog essay and media comments, Dalí proclaimed a return to form, control, structure and the Golden Section. Sales however were disappointing and the majority of critics did not believe there had been a major change in Dalí's work.[102]

On September 2, 1941, he hosted A Surrealistic Night in an Enchanted Forest in Monterey, a charity event which attracted national attention but raised little money for charity.[103][99]

The Museum of Modern Art held two major, simultaneous retrospectives of Dalí[104] and Joan Miró[105] from November 1941 to February 1942, Dalí being represented by forty-two paintings and sixteen drawings. Dalí's work attracted significant attention of critics and the exhibition later toured eight American cities, enhancing his reputation in America.[106]

In October 1942, Dalí's autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí was published simultaneously in New York and London and was reviewed widely by the press. Time magazine's reviewer called it "one of the most irresistible books of the year". George Orwell later wrote a scathing review in the Saturday Book.[107][108] A passage in the autobiography in which Dalí claimed that Buñuel was solely responsible for the anti-clericalism in the film L'Age d'Or may have indirectly led to Buñuel resigning his position at MoMA in 1943 under pressure from the State Department.[109][110] Dalí also published a novel Hidden Faces in 1944 with less critical and commercial success.[111]

In the catalog essay for his exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1943 Dalí continued his attack on the Surrealist movement, writing: "Surrealism will at least have served to give experimental proof that total sterility and attempts at automatizations have gone too far and have led to a totalitarian system. ... Today's laziness and the total lack of technique have reached their paroxysm in the psychological signification of the current use of the college [collage]".[112] The critical response to the society portraits in the exhibition, however, was generally negative.[113]

In November–December 1945 Dalí exhibited new work at the Bignou Gallery in New York. The exhibition included eleven oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, and illustrations. Works included Basket of Bread, Atomic and Uranian Melancholic Ideal, and My Wife Nude Contemplating her own Body Transformed into Steps, the Three Vertebrae of a Column, Sky and Architecture. The exhibition was notable for works in Dalí's new classicism style and those heralding his "atomic period".[114]

During the war years, Dalí was also engaged in projects in various other fields. He executed designs for a number of ballets including Labyrinth (1942), Sentimental Colloquy, Mad Tristan, and The Cafe of Chinitas (all 1944).[115] In 1945 he created the dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's film Spellbound.[116] He also produced artwork and designs for products such as perfumes, cosmetics, hosiery and ties.[117]

Postwar in United States (1946–48)

In 1946, Dalí worked with Walt Disney and animator John Hench on an unfinished animated film Destino.[118]

Dalí exhibited new work at the Bignou Gallery from November 1947 to January 1948. The 14 oil paintings and other works in the exhibition reflected Dalí's increasing interest in atomic physics. Notable works included Dematerialization Near the Nose of Nero (The Separation of the Atom), Intra-Atomic Equilibrium of a Swan's Feather, and a study for Leda Atomica. The proportions of the latter work were worked out in collaboration with a mathematician.[119]

In early 1948, Dalí's 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship was published. The book was a mixture of anecdotes, practical advice on painting, and Dalínian polemics.[120]

Later years in Spain

In 1948, Dalí and Gala moved back into their house in Port Lligat, on the coast near Cadaqués. For the next three decades, they would spend most of their time there, spending winters in Paris and New York.[5][60] Dalí's decision to live in Spain under Franco and his public support for the regime prompted outrage from many anti-Francoist artists and intellectuals. Pablo Picasso refused to mention Dalí's name or acknowledge his existence for the rest of his life.[121] In 1960, André Breton unsuccessfully fought against the inclusion of Dalí's Sistine Madonna in the Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanter's Domain exhibition organized by Marcel Duchamp in New York.[122] Breton and other Surrealists issued a tract to coincide with the exhibition denouncing Dalí as "the ex-apologist of Hitler... and friend of Franco".[123]

In December 1949 Dalí's sister Anna Maria published her book Salvador Dalí Seen by his Sister. Dalí was angered by passages that he considered derogatory towards his wife Gala and broke off relations with his family. When Dalí's father died in September 1950 Dalí learned that he had been virtually disinherited in his will. A two-year legal dispute followed over paintings and drawings Dalí had left in his family home, during which Dalí was accused of assaulting a public notary.[124]

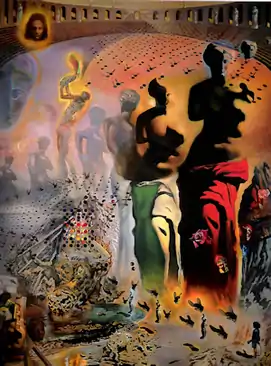

As Dalí moved further towards embracing Catholicism he introduced more religious iconography and themes in his painting. In 1949 he painted a study for The Madonna of Port Lligat (first version, 1949) and showed it to Pope Pius XII during an audience arranged to discuss Dalí 's marriage to Gala.[125] This work was a precursor to the phase Dalí dubbed "Nuclear Mysticism," a fusion of Einsteinian physics, classicism, and Catholic mysticism. In paintings such as The Madonna of Port Lligat, The Christ of Saint John on the Cross and The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, Dalí sought to synthesize Christian iconography with images of material disintegration inspired by nuclear physics.[126][127] His later Nuclear Mysticism works included La Gare de Perpignan (1965) and The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70).

Dalí's keen interest in natural science and mathematics was further manifested by the proliferation of images of DNA and rhinoceros horn shapes in works from the mid-1950s. According to Dalí, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral.[128] Dalí was also fascinated by the Tesseract (a four-dimensional cube), using it, for example, in Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

Dalí had been extensively using optical illusions such as double images, anamorphosis, negative space, visual puns and trompe-l'œil since his Surrealist period and this continued in his later work. At some point, Dalí had a glass floor installed in a room near his studio in Port Lligat. He made extensive use of it to study foreshortening, both from above and from below, incorporating dramatic perspectives of figures and objects into his paintings.[129]: 17–18, 172 He also experimented with the bulletist technique[130] pointillism, enlarged half-tone dot grids and stereoscopic images.[129] He was among the first artists to employ holography in an artistic manner.[131] In Dalí's later years, young artists such as Andy Warhol proclaimed him an important influence on pop art.[132]

In 1960, Dalí began work on his Theatre-Museum in his home town of Figueres. It was his largest single project and a main focus of his energy through to 1974, when it opened. He continued to make additions through the mid-1980s.[133][134]

In 1955, Dalí met Nanita Kalaschnikoff, who was to become a close friend, muse, and model.[135] At a French nightclub in 1965 Dalí met Amanda Lear, a fashion model then known as Peki Oslo. Lear became his protégée and one of his muses. According to Lear, she and Dalí were united in a "spiritual marriage" on a deserted mountaintop.[136][137]

Final years and death

In 1968, Dalí bought a castle in Púbol for Gala, and from 1971 she would retreat there for weeks at a time, Dalí having agreed not to visit without her written permission.[60] His fears of abandonment and estrangement from his longtime artistic muse contributed to depression and failing health.[5]

In 1980, at age 76, Dalí's health deteriorated sharply and he was treated for depression, drug addiction, and Parkinson-like symptoms, including a severe tremor in his right arm. There were also allegations that Gala had been supplying Dalí with pharmaceuticals from her own prescriptions.[138]

Gala died on 10 June 1982, at the age of 87. After her death, Dalí moved from Figueres to the castle in Púbol, where she was entombed.[5][60][139]

In 1982, King Juan Carlos bestowed on Dalí the title of Marqués de Dalí de Púbol[140][141] (Marquess of Dalí of Púbol) in the nobility of Spain, Púbol being where Dalí then lived. The title was initially hereditary, but at Dalí's request was changed to life-only in 1983.[140]

In May 1983, what was said to be Dalí's last painting, The Swallow's Tail, was revealed. The work was heavily influenced by the mathematical catastrophe theory of René Thom. However, some critics have questioned how Dalí could have executed a painting with such precision given the severe tremor in his painting arm.[142]

From early 1984 Dalí's depression worsened and he refused food, leading to severe undernourishment.[143] Dalí had previously stated his intention to put himself into a state of suspended animation as he had read that some microorganisms could do.[144] In August 1984 a fire broke out in Dalí's bedroom and he was hospitalized with severe burns. Two judicial inquiries found that the fire was caused by an electrical fault and no findings of negligence were made.[145] After his release from hospital Dalí moved to the Torre Galatea, an annex to the Dalí Theatre-Museum.[146]

There have been allegations that Dalí was forced by his guardians to sign blank canvases that could later be used in forgeries.[147] It is also alleged that he knowingly sold otherwise-blank lithograph paper which he had signed, possibly producing over 50,000 such sheets from 1965 until his death.[5] As a result, art dealers tend to be wary of late graphic works attributed to Dalí.[148]

In July 1986, Dalí had a pacemaker implanted. On his return to his Theatre-Museum he made a brief public appearance, saying:

When you are a genius, you do not have the right to die, because we are necessary for the progress of humanity.[149][150]

In November 1988, Dalí entered hospital with heart failure. On 5 December 1988, he was visited by King Juan Carlos, who confessed that he had always been a serious devotee of Dalí.[151] Dalí gave the king a drawing, Head of Europa, which would turn out to be Dalí's final drawing.

On the morning of 23 January 1989, Dalí died of cardiac arrest at the age of 84.[152] He is buried in the crypt below the stage of his Theatre-Museum in Figueres. The location is across the street from the church of Sant Pere, where he had his baptism, first communion, and funeral, and is only 450 metres (1,480 ft) from the house where he was born.[153]

Exhumation

On 26 June 2017 it was announced that a judge in Madrid had ordered the exhumation of Dalí's body in order to obtain samples for a paternity suit.[154] Joan Manuel Sevillano, manager of the Fundación Gala Salvador Dalí (The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation), denounced the exhumation as inappropriate.[155] The exhumation took place on the evening of 20 July, and his DNA was extracted.[156] On 6 September 2017 the Foundation stated that the tests carried out proved conclusively that Dalí and the claimant were not related.[157][158] On 18 May 2020 a Spanish court dismissed an appeal from the claimant and ordered her to pay the costs of the exhumation.[159]

Symbolism

From the late 1920s, Dalí progressively introduced many bizarre or incongruous images into his work which invite symbolic interpretation. While some of these images suggest a straightforward sexual or Freudian interpretation (Dalí read Freud in the 1920s) others (such as locusts, rotting donkeys, and sea urchins) are idiosyncratic and have been variously interpreted.[160] Some commentators have cautioned that Dalí's own comments on these images are not always reliable.[161]

Food

Food and eating have a central place in Dalí's thoughts and work. He associated food with beauty and sex and was obsessed with the image of the female praying mantis eating her mate after copulation.[162] Bread was a recurring image in Dalí's art, from his early work The Basket of Bread to later public performances such as in 1958 when he gave a lecture in Paris using a 12-meter-long baguette an illustrative prop.[163] He saw bread as "the elementary basis of continuity" and "sacred subsistence".[164]

The egg is another common Dalínian image. He connects the egg to the prenatal and intrauterine, thus using it to symbolize hope and love.[165] It appears in The Great Masturbator, The Metamorphosis of Narcissus and many other works. There are also giant sculptures of eggs in various locations at Dalí's house in Port Lligat[166] as well as at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres.

Both Dalí and his father enjoyed eating sea urchins, freshly caught in the sea near Cadaqués. The radial symmetry of the sea urchin fascinated Dalí, and he adapted its form to many artworks. Other foods also appear throughout his work.[167]

The famous "melting watches" that appear in The Persistence of Memory suggest Einstein's theory that time is relative and not fixed.[62] Dalí later claimed that the idea for clocks functioning symbolically in this way came to him when he was contemplating Camembert cheese.[168]

Animals

The rhinoceros and rhinoceros horn shapes began to proliferate in Dalí's work from the mid-1950s. According to Dalí, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral. He linked the rhinoceros to themes of chastity and to the Virgin Mary.[128] However, he also used it as an obvious phallic symbol as in Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity.[169]

Various other animals appear throughout Dalí's work: rotting donkeys and ants have been interpreted as pointing to death, decay, and sexual desire; the snail as connected to the human head (he saw a snail on a bicycle outside Freud's house when he first met Sigmund Freud); and locusts as a symbol of waste and fear.[165] The elephant is also a recurring image in his work; for example, Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening. The elephants are inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture base in Rome of an elephant carrying an ancient obelisk.[170]

Science

Dalí's life-long interest in science and mathematics was often reflected in his work. His soft watches have been interpreted as references to Einstein's theory of the relativity of time and space.[62] Images of atomic particles appeared in his work soon after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki[171] and strands of DNA appeared from the mid-1950s.[169] In 1958 he wrote in his Anti-Matter Manifesto: "In the Surrealist period, I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvelous, of my father Freud. Today, the exterior world and that of physics have transcended the one of psychology. My father today is Dr. Heisenberg."[172][173]

The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1954) harks back to The Persistence of Memory (1931) and in portraying that painting in fragmentation and disintegration has been interpreted as a reference to Heisenberg's quantum mechanics.[172]

Endeavors outside painting

Dalí was a versatile artist. Some of his more popular works are sculptures and other objects, and he is also noted for his contributions to theater, fashion, and photography, among other areas.

Sculptures and other objects

From the early 1930s, Dalí was an enthusiastic proponent of the proliferation of three-dimensional Surrealist Objects to subvert perceptions of conventional reality, writing: "museums will fast fill with objects whose uselessness, size and crowding will necessitate the construction, in deserts, of special towers to contain them."[174] His more notable early objects include Board of Demented Associations (1930–31), Retrospective Bust of a Woman (1933), Venus de Milo with Chest of Drawers (1936) and Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket (1936). Two of the most popular objects of the Surrealist movement were Lobster Telephone (1936) and Mae West Lips Sofa (1937) which were commissioned by art patron Edward James.[175] Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for Dalí who drew a close analogy between food and sex.[176] The telephone was functional, and James purchased four of them from Dalí to replace the phones in his home. The Mae West Lips Sofa was shaped after the lips of actress Mae West, who was previously the subject of Dalí's watercolor, The Face of Mae West which may be used as a Surrealist Apartment (1934–35).[175] In December 1936 Dalí sent Harpo Marx a Christmas present of a harp with barbed-wire strings.[177]

After World War II Dalí authorized many sculptures derived from his most famous works and images. In his later years other sculptures also appeared, often in large editions, whose authenticity has sometimes been questioned.[178]

Between 1941 and 1970, Dalí created an ensemble of 39 pieces of jewelry, many of which are intricate, some containing moving parts. The most famous assemblage, The Royal Heart, is made of gold and is encrusted with 46 rubies, 42 diamonds, and four emeralds, created in such a way that the center "beats" like a heart.[179]

Dalí ventured into industrial design in the 1970s with a 500-piece run of Suomi tableware by Timo Sarpaneva that Dalí decorated for the German Rosenthal porcelain maker's "Studio Linie".[180] In 1969 he designed the Chupa Chups logo.[181] He facilitated the design of the advertising campaign for the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest and created a large on-stage metal sculpture that stood at the Teatro Real in Madrid.[182][183]

Theater and film

In theater, Dalí designed the scenery for Federico García Lorca's 1927 romantic play Mariana Pineda.[184] For Bacchanale (1939), a ballet based on and set to the music of Richard Wagner's 1845 opera Tannhäuser, Dalí provided both the set design and the libretto.[185] He executed designs for a number of other ballets including Labyrinth (1942), Sentimental Colloquy, Mad Tristan, The Cafe of Chinitas (all 1944) and The Three-Cornered Hat (1949).[186][115]

Dalí became interested in film when he was young, going to the theater most Sundays.[187] By the late 1920s he was fascinated by the potential of film to reveal "the unlimited fantasy born of things themselves"[188] and went on to collaborate with the director Luis Buñuel on two Surrealist films: the 17-minute short Un Chien Andalou (1929) and the feature film L'Age d'Or (1930). Dalí and Buñuel agree that they jointly developed the script and imagery of Un Chien Andalou, but there is controversy over the extent of Dalí's contribution to L'Age d'Or.[189] Un Chien Andalou features a graphic opening scene of a human eyeball being slashed with a razor and develops surreal imagery and irrational discontinuities in time and space to produce a dreamlike quality.[190] L'Age d'Or is more overtly anti-clerical and anti-establishment, and was banned after right-wing groups staged a riot in the Parisian theater where it was being shown.[191] Summarizing the impact of these two films on the Surrealist film movement, one commentator has stated: "If Un Chien Andalou stands as the supreme record of Surrealism's adventures into the realm of the unconscious, then L'Âge d'Or is perhaps the most trenchant and implacable expression of its revolutionary intent."[192]

After he collaborated with Buñuel, Dalí worked on several unrealized film projects including a published script for a film, Babaouo (1932); a scenario for Harpo Marx called Giraffes on Horseback Salad (1937); and an abandoned dream sequence for the film Moontide (1942).[193] In 1945 Dalí created the dream sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound, but neither Dalí nor the director was satisfied with the result.[194] Dalí also worked with Walt Disney and animator John Hench on the short film Destino in 1946.[118] After initially being abandoned, the animated film was completed in 2003 by Baker Bloodworth and Walt Disney's nephew Roy E. Disney. Between 1954 and 1961 Dalí worked with photographer Robert Descharnes on The Prodigious History of the Lacemaker and the Rhinoceros, but the film was never completed.[195]

In the 1960s Dalí worked with some directors on documentary and performance films including with Philippe Halsman on Chaos and Creation (1960), Jack Bond on Dalí in New York (1966) and Jean-Christophe Averty on Soft Self-Portrait of Salvador Dalí (1966).[196]

Dalí collaborated with director José-Montes Baquer on the pseudo-documentary film Impressions of Upper Mongolia (1975), in which Dalí narrates a story about an expedition in search of giant hallucinogenic mushrooms.[197] In the mid-1970s film director Alejandro Jodorowsky initially cast Dalí in the role of the Padishah Emperor in a production of Dune, based on the novel by Frank Herbert. However, Jodorowsky changed his mind after Dalí publicly supported the execution of alleged ETA terrorists in December 1975. The film was ultimately never made.[198][199]

In 1972 Dalí began to write the scenario for an opera-poem called Être Dieu (To Be God). The Spanish writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán wrote the libretto and Igor Wakhévitch the music. The opera poem was recorded in Paris in 1974 with Dalí in the role of the protagonist.[200]

Fashion and photography

_09633u.jpg.webp)

Fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli worked with Dalí from the 1930s and commissioned him to produce a white dress with a lobster print. Other designs Dalí made for her include a shoe-shaped hat and a pink belt with lips for a buckle. He was also involved in creating textile designs and perfume bottles. In 1950, Dalí created a special "costume for the year 2045" with Christian Dior.[201]

Photographers with whom he collaborated include Man Ray, Brassaï, Cecil Beaton, and Philippe Halsman. Halsman produced the Dalí Atomica series (1948) – inspired by Dalí's painting Leda Atomica – which in one photograph depicts "a painter's easel, three cats, a bucket of water, and Dalí himself floating in the air".[201]

Architecture

Dalí's architectural achievements include his Port Lligat house near Cadaqués, as well as his Theatre Museum in Figueres. A major work outside of Spain was the temporary Dream of Venus Surrealist pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair, which contained several unusual sculptures and statues, including live performers posing as statues.[92] In 1958, Dalí completed Crisalida, a temporary installation promoting a drug, which was exhibited at a medical convention in San Francisco.[202]

Literary works

In his only novel, Hidden Faces (1944), Dalí describes the intrigues of a group of eccentric aristocrats whose extravagant lifestyle symbolizes the decadence of the 1930s. The Comte de Grandsailles and Solange de Cléda pursue a love affair, but interwar political turmoil and other vicissitudes drive them apart. It is variously set in Paris, rural France, Casablanca in North Africa, and Palm Springs in the United States. Secondary characters include aging widow Barbara Rogers, her bisexual daughter Veronica, Veronica's sometime female lover Betka, and Baba, a disfigured U.S. fighter pilot.[203] The novel was written in New York, and translated by Haakon Chevalier.[111]

His other literary works include The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942), Diary of a Genius (1966), and Oui: The Paranoid-Critical Revolution (1971). Dalí also published poetry, essays, art criticism, and a technical manual on art.[204]

Graphic arts

Dalí worked extensively in the graphic arts, producing many drawings, etchings, and lithographs. Among the most notable of these works are forty etchings for an edition of Lautréamont's The Songs of Maldoror (1933) and eighty drypoint reworkings of Goya's Caprichos (1973–77).[205] From the 1960s, however, Dalí would often sell the rights to images but not be involved in the print production itself. In addition, a large number of fakes were produced in the 1980s and 1990s, thus further confusing the Dalí print market.[148]

Book illustrations were an important part of Dalí's work throughout his career. His first book illustration was for the 1924 publication of the Catalan poem Les bruixes de Llers ("The Witches of Liers") by his friend and schoolmate, poet Carles Fages de Climent.[206][207][208] His other notable book illustrations, apart from The Songs of Maldoror, include 101 watercolors and engravings for The Divine Comedy (1960) and 100 drawings and watercolors for The Arabian Nights (1964).[209]

Politics and personality

Politics and religion

As a youth, Dalí identified as communist, anti-monarchist and anti-clerical,[210] and in 1924 he was briefly imprisoned by the Primo de Rivera dictatorship as a person "intensely liable to cause public disorder".[211] When Dalí officially joined the Surrealist group in 1929 his political activism initially intensified. In 1931, he became involved in the Workers' and Peasants' Front, delivering lectures at meetings and contributing to their party journal.[212] However, as political divisions within the Surrealist group grew, Dalí soon developed a more apolitical stance, refusing to publicly denounce fascism. In 1934, André Breton accused him of being sympathetic to Hitler and Dalí narrowly avoided being expelled from the group.[213] In 1935 Dalí wrote a letter to Breton suggesting that non-white races should be enslaved.[214] After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Dalí avoided taking a public stand for or against the Republic.[84] However, immediately after Franco's victory in 1939, Dalí praised Catholicism and the Falange and was expelled from the Surrealist group.[94]

After Dalí's return to his native Catalonia in 1948, he publicly supported Franco's regime and announced his return to the Catholic faith.[215] Dalí was granted an audience with Pope Pius XII in 1949 and with Pope John XXIII in 1959. He had official meetings with General Franco in June 1956, October 1968, and May 1974.[216] In 1968, Dalí stated that on Franco's death there should be no return to democracy and Spain should become an absolute monarchy.[217] In September 1975, Dalí publicly supported Franco's decision to execute three alleged Basque terrorists and repeated his support for an absolute monarchy, adding: "Personally, I'm against freedom; I'm for the Holy Inquisition." In the following days, he fled to New York after his home in Port Lligat was stoned and he had received numerous death threats.[218] When King Juan Carlos visited the ailing Dalí in August 1981, Dalí told him: "I have always been an anarchist and a monarchist."[219]

Dalí espoused a mystical view of Catholicism and in his later years he claimed to be a Catholic and an agnostic.[220] He was interested in the writings of the Jesuit priest and philosopher Teilhard de Chardin[221] and his Omega Point theory. Dalí's painting Tuna Fishing (Homage to Meissonier) (1967) was inspired by his reading of Chardin.[222]

Sexuality

Dalí's sexuality had a profound influence on his work. He stated that as a child he saw a book with graphic illustrations of venereal diseases and this provoked a life-long disgust of female genitalia and a fear of impotence and sexual intimacy. Dalí frequently stated that his main sexual activity involved voyeurism and masturbation and his preferred sexual orifice was the anus.[223] Dalí said that his wife Gala was the only person with whom he had achieved complete coitus.[224] From 1927 Dalí's work featured graphic and symbolic sexual images usually associated with other images evoking shame and disgust. Images of anality and excrement also abound in his work from this time. Some of the most notable works reflecting these themes include The First Days of Spring (1929), The Great Masturbator (1929), and The Lugubrious Game (1929). Several of Dalí's intimates in the 1960s and 1970s have stated that he would arrange for selected guests to perform choreographed sexual activities to aid his voyeurism and masturbation.[225][226][227]

Personality

Dalí was renowned for his eccentric and ostentatious behavior throughout his career. In 1941, the Director of Exhibitions and Publications at MoMA wrote: "The fame of Salvador Dalí has been an issue of particular controversy for more than a decade...Dalí's conduct may have been undignified, but the greater part of his art is a matter of dead earnest."[228] When Dalí was elected to the French Academy of Fine Arts in 1979, one of his fellow academicians stated that he hoped Dalí would now abandon his "clowneries".[229]

In 1936, at the premiere screening of Joseph Cornell's film Rose Hobart at Julien Levy's gallery in New York City, Dalí knocked over the projector in a rage. "My idea for a film is exactly that," he said shortly afterward, "I never wrote it down or told anyone, but it is as if he had stolen it!"[230] In 1939, while working on a window display for Bonwit Teller, he became so enraged by unauthorized changes to his work that he pushed a display bathtub through a plate glass window.[5] In 1955, he delivered a lecture at the Sorbonne, arriving in a Rolls-Royce full of cauliflowers.[231] To promote Robert Descharnes' 1962 book The World of Salvador Dalí, he appeared in a Manhattan bookstore on a bed, wired up to a machine that traced his brain waves and blood pressure. He would autograph books while thus monitored, and the book buyer would also be given the paper chart recording.[5]

After World War II, Dalí became one of the most recognized artists in the world, and his long cape, walking stick, haughty expression, and upturned waxed mustache became icons of his brand. His boastfulness and public declarations of his genius became essential elements of the public Dalí persona: "every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí".[232]

Dalí frequently traveled with his pet ocelot Babou, even bringing it aboard the luxury ocean liner SS France.[233]

Dalí's fame meant he was a frequent guest on television in Spain, France and the United States, including appearances on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson on 7 January 1963[234] The Mike Wallace Interview[235] and the panel show What's My Line?.[236][237] Dalí appeared on The Dick Cavett Show on 6 March 1970 carrying an anteater.[238] He also appeared in numerous advertising campaigns such as Lanvin chocolates[239][240] and Braniff International Airlines in 1968.[241]

Legacy

Two major museums are devoted to Dalí's work: the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, and the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S.

Dalí's life and work have been an important influence on pop art, other Surrealists, and contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst.[7][8] He has been portrayed on film by Robert Pattinson in Little Ashes (2008), by Adrien Brody in Midnight in Paris (2011), and by Ben Kingsley in Daliland. The Salvador Dalí Desert in Bolivia and the Dalí crater on the planet Mercury are named for him.[242][243]

The Spanish television series Money Heist (2017–2021) includes characters wearing a costume of red jumpsuits and Dalí masks.[244] The creator of the series stated that the Dalí mask was chosen because it was an iconic Spanish image.[245] The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation protested against the use of Dalí's image without the authorisation of the Dalí estate.[246]

The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation currently serves as his official estate.[247] The US copyright representative for the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.[248]

Honors

- 1964: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[249]

- 1972: Associate member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium[250]

- 1978: Associate member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France[251]

- 1981: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III[252]

- 1982: Created 1st Marquess of Dalí of Púbol, by King Juan Carlos[141]

List of selected works

Dalí produced over 1,600 paintings and numerous graphic works, sculptures, three-dimensional objects, and designs.[253] Below is a sample of important and representative works.

- Landscape Near Figueras (1910–1914)

- Vilabertran (1910–1914)

- Cabaret Scene (1922)

- Night Walking Dreams (1922)

- The Basket of Bread (1926)

- Composition with Three Figures (Neo-Cubist Academy) (1927)

- Honey is Sweeter than Blood (1927)

- Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) (1929) (film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel)

- The Lugubrious Game (1929)

- The Great Masturbator (1929)

- The First Days of Spring (1929)

- L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) (1930) (film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel)

- Board of Demented Associations (1930–1931) (Surrealist object)

- Premature Ossification of a Railway Station (1931)

- The Persistence of Memory (1931)

- Retrospective Bust of a Woman (1933) (mixed media sculpture collage)

- The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table (c.1934)

- Lobster Telephone (1936)

- Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936)

- Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936)

- Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937)

- Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937)

- The Burning Giraffe (1937)

- Mae West Lips Sofa (1937)

- Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach (1938)

- Shirley Temple, The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in Her Time (1939)

- Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire (1940)

- The Face of War (also known as The Visage of the War) (1940)

- Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man (1943)

- Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (c. 1944)

- Basket of Bread – Rather Death than Shame (1945)

- The Temptation of St. Anthony (1946)

- The Elephants (1948) (also known as Project for "As You Like It")

- Leda Atomica (1947–1949)

- The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949)

- Christ of Saint John of the Cross (also known as The Christ) (1951)

- Galatea of the Spheres (1952) (also known as Gala Placidia)

- The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1952–1954)

- Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (c. 1954) (also known as Hypercubic Christ)

- Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity (1954)

- The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955)

- Still Life Moving Fast (c. 1956) (also known as Fast-Moving Still Life)

- The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1958)

- Perpignan Railway Station (c. 1965)

- Tuna Fishing (1966–1967)

- The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1970)

- Nieuw Amsterdam (1974 object/sculpture)

- The Swallow's Tail (c.1983)

Dalí museums and permanent exhibitions

- Dalí Theatre-Museum – Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, holds the largest collection of Dalí's work

- Gala Dalí House-Museum – Castle of Púbol in Púbol, Catalonia, Spain

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (Reina Sofia Museum) – Madrid, Spain, holds a significant collection

- Salvador Dalí House Museum – Port Lligat, Catalonia, Spain

- Salvador Dalí Museum – St Petersburg, Florida, contains the collection of Reynolds and Eleanor Morse, and over 1500 works by Dalí, including seven large "masterworks".

Gallery

Gala in the Window (1933), Marbella

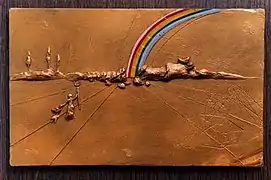

Gala in the Window (1933), Marbella The Rainbow (1972), M.T. Abraham Foundation

The Rainbow (1972), M.T. Abraham Foundation Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas (1956), Puerto José Banús

Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas (1956), Puerto José Banús_08.jpg.webp) Plaza de Dalí (Dalí Square), Madrid

Plaza de Dalí (Dalí Square), Madrid Perseo (Perseus), Marbella

Perseo (Perseus), Marbella Children at Dalí exhibition in Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

Children at Dalí exhibition in Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

Notes

- Dalí's name varied over his life. His birth name was officially registered as Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí Doménech. His first names were in Spanish and his surnames castilianized despite being born in Catalonia, as at the time the Catalan language was banned from official acts. His complete name in Catalan is Salvador Domènec Felip Jacint Dalí i Domènech. In 1977 Catalan names were legalized, and he adopted the hybrid form (first names in Spanish, surnames in Catalan). This form and the purely Spanish and Catalan forms can all be seen in print today.

- In isolation, Dalí is pronounced [dəˈli] in Catalan and [daˈli] in Spanish.

References

- "Dalí" Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.; "Dalí" Archived 29 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, London, Faber and Faber, 1997, Chs 2, 3

- Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dali (1997)

- Saladyga, Stephen Francis (2006). "The Mindset of Salvador Dalí". Lamplighter. Niagara University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- Meisler, Stanley (April 2005). "The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), passim

- Koons, Jeff (March 2005). "Who Paints Bread Better than Dali". Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Salvador Dalí's iconic Lobster Telephone acquired by National Galleries of Scotland". National Galleries Scotland. 17 December 2018. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 22

- "Dalí recupera su casa natal, que será un museo en 2010". El País. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 6, 459, 633, 689

- Llongueras, Lluís. (2004) Dalí, Ediciones B – Mexico. ISBN 84-666-1343-9.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 16, 82, 634, 644

- Rojas, Carlos. Salvador Dalí, Or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother's Portrait Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Penn State Press (1993). ISBN 0-271-00842-3.

- Gibson, Ian (1997)

- Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1948, London: Vision Press, p. 33

- Ian Gibson (1997). The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí. W. W. Norton & Company. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017. Gibson found out that "Dalí" (and its many variants) is an extremely common surname in Arab countries like Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria or Egypt. On the other hand, also according to Gibson, Dalí's mother's family, the Domènech of Barcelona, had Jewish roots.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 238–39

- Dalí, Secret Life, p. 2

- Gibson, Ian (1997). p. 23

- Gibson, Ian (1997). p. 109

- Martín Otín, José Antonio (2011). "Un tanguito de arrabal". El fútbol tiene música. Córner. ISBN 978-84-15242-00-0. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Who was Salvador Dalí?|Collection|Morohashi Museum of Modern Art". dali.jp. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 78–81

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 82

- Dalí, Secret Life, pp. 152–53

- As listed in his prison record of 1924 Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, aged 20. However, his hairdresser and biographer, Luis Llongueras, stated Dalí was 1.74 metres (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in) tall.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 90

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 92–98

- For more in-depth information about the Lorca-Dalí connection see Lorca-Dalí: el Amor Que no pudo ser and The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, both by Ian Gibson.

- Bosquet, Alain, Conversations with Dalí Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 1969. pp. 19–20. (PDF)

- "Salvador Dalí and the Museo del Prado: A Prolonged Fascination | Fundació Gala - Salvador Dalí". Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Salvador Dalí and the Museo del Prado: A Prolonged Fascination | Fundació Gala - Salvador Dalí". Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Michael Elsohn Ross, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Review Press, 2003, p. 24. ISBN 1-61374-275-4

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 97–98

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 116–119

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 123–25

- Fèlix Fanés, Salvador Dalí: The Construction of the Image, 1925–1930 Archived 22 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-300-09179-6

- "Exposició Salvador Dalí, Galeries Dalmau, 14–28 November 1925, exhibition catalog". Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 126–27

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 130–31

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 163

- "Paintings Gallery No. 5". Dali-gallery.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Elisenda Andrés Pàmies, Les Galeries Dalmau, un project de modernist a la Ciutat de Barcelona Archived 9 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 2012–13, Facultat d’Humanitats, Universitat Pompeu Fabra

- "Exposició de Salvador Dalí, Galeries Dalmau, Passeig de Gràcia, 31 December 1926 – 14 January 1927, exhibition catalog (other versions)". Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 147–49

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 162

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 171

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 287

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 186–190

- Hodge, Nicola, and Libby Anson. The A–Z of Art: The World's Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works. California: Thunder Bay Press, 1996. Online citation.

- "Phelan, Joseph". Artcyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Roger Rothman, Tiny Surrealism: Salvador Dal and the Aesthetics of the Small Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, U of Nebraska Press, 2012. p. 202. ISBN 0-300-12106-7

- Salvador Dali and the Spanish Baroque: From Still Life to Velazquez Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Salvado Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Fl. 2007

- Koller, Michael (January 2001). "Un Chien Andalou". Senses of Cinema (in French). Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- Shelley, Landry. "Dalí Wows Crowd in Philadelphia" Archived 8 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Unbound (The College of New Jersey) Spring 2005. Retrieved on 22 July 2006.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 218–20

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 206–08, 231–32

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 237

- "Gala Biography". Dalí. Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Clocking in with Salvador Dalí: Salvador Dalí's Melting Watches Archived 21 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) from the Salvador Dalí Museum. Retrieved on 19 August 2006.

- Salvador Dalí, La Conquête de l'irrationnel (Paris: Éditions surréalistes, 1935), p. 25.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 279–283, 299–300

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 314–15

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 316

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 323

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 492

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 421–22, 508–10, 620–21

- Amengual, Margalida (14 December 2016). "An opera on the relationship between Salvador Dalí and Gala arrives at Barcelona's Liceu". Catalan News Agency (CNA). Intracatalònia, SA. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 336–41

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 342–43

- Greeley, Robin Adèle (2006). Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-300-11295-5.

- Clements, Paul (2016). The Creative Underground : Art, Politics and Everyday Life. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-50128-2. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Shanes, Eric (2012). The Life and Masterworks of Salvador Dalí Archived 9 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Parkstone. p. 53. ISBN 1-78042-879-0.

- Salvador Dalí, Louis Pauwels, Les passions Selon Dalí Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Denoël, 1968

- Pierre Ajame, La Double vie de Salvador Dalí: récit Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Éditions Ramsay, 1984, p. 125

- Jackaman, Rob. (1989) The Course of English Surrealist Poetry Since the 1930s Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-932-6.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 359–60

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 358–59

- Gibson, Ian (1997). pp. 334, 364–67

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 306–308

- "Salvador Dalí Lobster Telephone". National Gallery of Australia. August 1994. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 361–63

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 376-77, and passim

- "Salvador Dalí's Biography – Gala". salvador-dali.org. Salvador Dalí Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 November 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Herbert, James D. (1998). Paris 1937. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8014-3494-5. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Cohen-Solal, Annie (2010). Leo and His Circle. ISBN 978-1-4000-4427-6. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Rubin, William S. 1968. Dada and Surrealist Art. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York. 525 pp.

- Salvador Dalí Exhibition, Exhibition Catalogue – 16 February through 15 May 2005

- Fischer, John. "Salvador Dalí Exhibition". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 389–90

- Schaffner, Ingrid, Photogr. by Eric Schaal (2002). Salvador Dalí's "Dream of Venus": the surrealist funhouse from the 1939 World's Fair (1. ed.). New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-359-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 391-92

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 395

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 387, 396–97

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 453

- "Dalí". Sousa Mendes Foundation. 20 June 1940. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Schmalz, David. "A world-class Salvador Dalí art collection comes to Monterey". Monterey County Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 411–12

- Crowder, Bland (31 January 2014). "¡Hola, Dalí!". Virginia Living. Cape Fear Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 404–05

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 409–11

- Neal Hotelling (26 August 2022). "Call the sheriff, Dali's been robbed" (PDF). Carmel Pine Cone. Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- Soby, James Thrall. 1941. Salvador Dali: Paintings, Drawings, Prints. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 87 pp.

- Sweeney, James Johnson. 1941. Joan Miro. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 87 pp.

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 413–16

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 416–20.

- Orwell, George "Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí" Archived 21 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. theorwellprize.co.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel (Vintage, 1984) ISBN 0-8166-4387-3

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 419

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 424–30

- Descharnes, Robert and Nicolas. Salvador Dalí. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1993. p. 35.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 423

- Gibson, (Ian) (1997), pp. 434–36

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 431–43

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 434-45

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 430–31

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 436–38

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 440–42

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 442–44

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 470

- Ignacio Javier López. The Old Age of William Tell (A study of Buñuel's Tristana). MLN 116 (2001): 295–314.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 497-98

- Gibson, Ian (1997), pp. 454–61

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 450–53

- "Salvador Dalí Bio, Art on 5th". Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 461–63

- Elliott H. King in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dalí, Bompiani Arte, Milan, 2004, p. 456.

- Ades, Dawn, ed. (2000). Dalí's optical illusions : [Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, January 21 – March 26, 2000 : Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, April 19 – June 18, 2000; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, July 25 – October 1, 2000]. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08177-0.

- "The Phantasmagoric Universe – Espace Dalí À Montmartre". Bonjour Paris (in French). Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- The History and Development of Holography Archived 12 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Holophile. Retrieved on 22 August 2006.

- "Hello, Dalí". Carnegie Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- Pitxot, Antoni; Montse Aguer Teixidor; photography, Jordi Puig; translation, Steve Cedar (2007). The Dalí Theatre-Museum. Sant Lluís, Menorca: Triangle Postals. ISBN 978-84-8478-288-9.

- "Figueres: Teatre Museu Dalí – History". Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 483–97

- Prose, Francine. (2000) The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists they Inspired Archived 18 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-055525-4.

- Lear, Amanda. (1986) My Life with Dalí. Beaufort Books. ISBN 0-8253-0373-7.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 574–79

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 589–91

- Excerpts from the BOE Archived 5 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Website Heráldica y Genealogía Hispana

- Dalí as "Marqués de Dalí de Púbol" Archived 30 June 2012 at archive.today – Boletín Oficial del Estado, the official gazette of the Spanish government

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 603–604

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 602, 610

- "Salvador Dalí – Paths to Immortality". History of Art. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 604–10

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 610

- Mark Rogerson (1989). The Dalí Scandal: An Investigation. Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-03786-1.

- Forde, Kevin (2011). Investing in Collectables: An Investor's Guide to Turning Your Passion Into a Portfolio Archived 4 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Wiley. p. 170. ISBN 1-74246-821-7.

- "Somatemps Catalanitat és Hispanitat, Última entrevista a Dalí: "¡Viva el Rey, viva España, viva Cataluña!" (video), published 26 March 2017". 26 March 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- "El País, Dalí vuelve a casa, 17 July 1986". El País (in Spanish). 16 July 1986. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Etherington-Smith, Meredith, The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dalí Archived 19 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 411, 1995 Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80662-2

- Artner, Alan G. (24 January 1989). "Surrealist painter Salvador Dali, flamboyant art revolutionary". Chicago Tribune. p. 9. ProQuest 1015353001. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- Etherington-Smith, Meredith, The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dalí, pp. xxiv, 411–12, 1995, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80662-2

- "La exhumación del cuerpo de Salvador Dalí se inicia hoy a partir de las 20 horas". Marca (in Spanish). 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Grael, Vanessa (21 July 2017). "La fundación Gala Salvador Dalí carga contra la exhumación del pintor: "Queremos una compensación patrimonial"". El Mundo (in Spanish). Figueres. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- Redacción (20 July 2017). "Muelas, uñas y huesos: las pruebas que demostrarán la supuesta paternidad de Dalí". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Salvador Dalí: DNA test proves woman is not his daughter" Archived 16 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News.

- Josep, Fita (21 July 2017). "El bigote de Dalí sigue intacto, marcando las 10 y 10, es un milagro". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Barcelona. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- "Court dismisses appeal from woman claiming to be Salvador Daíi's daughter". The Guardian. 19 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 207–08

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 478

- Gibson, Ian (1997), p. 312

- Pine, Julia (1 January 2010). "Breaking Dalinian Bread". InVisible Culture. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Dalí, Salvador (1993). The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. New York: Dover Publications. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-486-27454-6.

- "Salvador Dalí's symbolism". County Hall Gallery. Archived from the original on 2 December 2006. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- Stone, Peter (7 May 2007). Frommer's Barcelona (2nd ed.). Wiley Publishing Inc. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-470-09692-5. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Salvador Dalí: Liquid Desire". ngv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dial Press, 1942), p. 317.

- Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 478

- Michael Taylor in Dawn Adès (ed.), Dalí (Milan: Bompiani, 2004), p. 342

- Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 433–34

- Datta, Suman. "Dalí: Explorations into the domain of science". The Triangle Online. College Publisher. p. 1. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2006.