Samlesbury witches

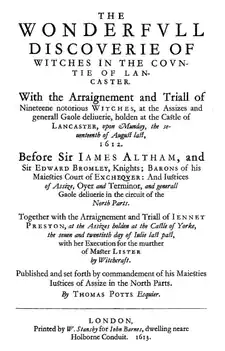

The Samlesbury witches were three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. Their trial at Lancaster Assizes in England on 19 August 1612 was one in a series of witch trials held there over two days, among the most infamous in English history.[2] The trials were unusual for England at that time in two respects: Thomas Potts, the clerk to the court, published the proceedings in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster; and the number of the accused found guilty and hanged was unusually high, ten at Lancaster and another at York.[3] All three of the Samlesbury women were acquitted.

The charges against the women included child murder and cannibalism. In contrast, the others tried at the same assizes, who included the Pendle witches, were accused of maleficium – causing harm by witchcraft.[4] The case against the three women collapsed "spectacularly" when the chief prosecution witness, Grace Sowerbutts, was exposed by the trial judge to be "the perjuring tool of a Catholic priest".[1]

Many historians, notably Hugh Trevor-Roper, have suggested that the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries were a consequence of the religious struggles of the period, with both the Catholic and Protestant Churches determined to stamp out what they regarded as heresy.[5] The trial of the Samlesbury witches is perhaps one example of that trend; it has been described as "largely a piece of anti-Catholic propaganda",[6] and even as a show-trial, to demonstrate that Lancashire, considered at that time to be a wild and lawless region, was being purged not only of witches but also of "popish plotters" (i.e., recusant Catholics).[7]

Background

King James I, who came to the English throne from Scotland in 1603, had a keen interest in witchcraft. By the early 1590s, he was convinced that Scottish witches were plotting against him.[8] His 1597 book, Daemonologie, instructed his followers that they must denounce and prosecute any supporters or practitioners of witchcraft. In 1604, the year following James's accession to the English throne, a new witchcraft law was enacted, "An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits", imposing the death penalty for causing harm by the use of magic or the exhumation of corpses for magical purposes.[9] James was, however, sceptical of the evidence presented in witch trials, even to the extent of personally exposing discrepancies in the testimonies presented against some accused witches.[10]

The accused witches lived in Lancashire, an English county which, at the end of the 16th century, was regarded by the authorities as a wild and lawless region, "fabled for its theft, violence and sexual laxity, where the church was honoured without much understanding of its doctrines by the common people".[11] Since the death of Queen Mary and the accession to the throne of her half-sister Elizabeth in 1558, Catholic priests had been forced into hiding, but in remote areas like Lancashire they continued to celebrate mass in secret.[12] In early 1612, the year of the trials, each justice of the peace (JP) in Lancashire was ordered to compile a list of the recusants in their area – those who refused to attend the services of the Church of England, a criminal offence at that time.[13]

Southworth family

The 16th-century English Reformation, during which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church, split the Southworth family of Samlesbury Hall. Sir John Southworth, head of the family, was a leading recusant who had been arrested several times for refusing to abandon his Catholic faith. His eldest son, also called John, did convert to the Church of England, for which he was disinherited, but the rest of the family remained staunchly Catholic.[15]

One of the accused witches, Jane Southworth, was the widow of the disinherited son, John. Relations between John and his father do not seem to have been amicable; according to a statement made by John Singleton, in which he referred to Sir John as his "old Master", Sir John refused even to pass his son's house if he could avoid it, and believed that Jane would probably kill her husband.[15][16] Jane Southworth (née Sherburne) and John were married in about 1598, and the couple lived in Samlesbury Lower Hall. Jane had been widowed only a few months before her trial for witchcraft in 1612, and had seven children.[17]

Investigations

On 21 March 1612, Alizon Device, who lived just outside the Lancashire village of Fence, near Pendle Hill,[18] encountered John Law, a pedlar from Halifax. She asked him for some pins, which he refused to give to her,[19] and a few minutes later Law suffered a stroke, for which he blamed Alizon.[20] Along with her mother Elizabeth and her brother James, Alizon was summoned to appear before local magistrate Roger Nowell on 30 March 1612. Based on the evidence and confessions he obtained, Nowell committed Alizon and ten others to Lancaster Gaol to be tried at the next assizes for maleficium, causing harm by witchcraft.[21]

Other Lancashire magistrates learned of Nowell's discovery of witchcraft in the county, and on 15 April 1612 JP Robert Holden began investigations in his own area of Samlesbury.[14] As a result, eight individuals were committed to Lancaster Assizes, three of whom – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – were accused of practising witchcraft on Grace Sowerbutts, Jennet's granddaughter and Ellen's niece.[22]

Trial

The trial was held on 19 August 1612 before Sir Edward Bromley,[23] a judge seeking promotion to a circuit nearer London, and who might therefore have been keen to impress King James, the head of the judiciary.[24] Before the trial began, Bromley ordered the release of five of the eight defendants from Samlesbury, with a warning about their future conduct.[22] The remainder – Jane Southworth, Jennet Bierley, and Ellen Bierley – were accused of using "diverse devillish and wicked Arts, called Witchcrafts, Inchauntments, Charmes, and Sorceries, in and upon one Grace Sowerbutts", to which they pleaded not guilty.[25] Fourteen-year-old Grace was the chief prosecution witness.[26]

Grace was the first to give evidence. In her statement she claimed that both her grandmother and aunt, Jennet and Ellen Bierley, were able to transform themselves into dogs and that they had "haunted and vexed her" for years.[27] She further alleged that they had transported her to the top of a hayrick by her hair, and on another occasion had tried to persuade her to drown herself. According to Grace, her relatives had taken her to the house of Thomas Walshman and his wife, from whom they had stolen a baby to suck its blood. Grace claimed that the child died the following night, and that after its burial at Samlesbury Church Ellen and Jennet dug up the body and took it home, where they cooked and ate some of it and used the rest to make an ointment that enabled them to change themselves into other shapes.[28]

Grace also alleged that her grandmother and aunt, with Jane Southworth, attended sabbats held every Thursday and Sunday night at Red Bank, on the north shore of the River Ribble. At those secret meetings they met with "foure black things, going upright, and yet not like men in the face", with whom they ate, danced, and had sex.[29]

Thomas Walshman, the father of the baby allegedly killed and eaten by the accused, was the next to give evidence. He confirmed that his child had died of unknown causes at about one year old. He added that Grace Sowerbutts was discovered lying as if dead in his father's barn on about 15 April, and did not recover until the following day.[30] Two other witnesses, John Singleton and William Alker, confirmed that Sir John Southworth, Jane Southworth's father-in-law, had been reluctant to pass the house where his son lived, as he believed Jane to be an "evil woman, and a Witch".[31]

Examinations

Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes, records that after hearing the evidence many of those in court were persuaded of the accused's guilt. On being asked by the judge what answer they could make to the charges laid against them, Potts reports that they "humbly fell upon their knees with weeping teares", and "desired him [Bromley] for Gods cause to examine Grace Sowerbutts". Immediately "the countenance of this Grace Sowerbutts changed"; the witnesses "began to quarrel and accuse one another", and eventually admitted that Grace had been coached in her story by a Catholic priest they called Thompson. Bromley then committed the girl to be examined by two JPs, William Leigh and Edward Chisnal.[32] Under questioning Grace readily admitted that her story was untrue, and said she had been told what to say by Jane Southworth's uncle,[7] Christopher Southworth aka Thompson, a Jesuit priest who was in hiding in the Samlesbury area.[33] Southworth was the chaplain at Samlesbury Hall,[34] and Jane Southworth's uncle by marriage.[17] Leigh and Chisnal questioned the three accused women in an attempt to discover why Southworth might have fabricated evidence against them, but none could offer any reason other than that each of them "goeth to the [Anglican] Church".[35]

After the statements had been read out in court Bromley ordered the jury to find the defendants not guilty, stating that:

God hath delivered you beyond expectation, I pray God you may use this mercie and favour well; and take heed you fall not hereafter: And so the court doth order that you shall be delivered.[36]

Potts concludes his account of the trial with the words: "Thus were these poore Innocent creatures, by the great care and paines of this honourable Judge, delivered from the danger of this Conspiracie; this bloudie practise of the Priest laid open".[37]

The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster

Almost everything that is known about the trials comes from a report of the proceedings written by Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes. Potts was instructed to write his account by the trial judges, and had completed the work by 16 November 1612. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be "truly reported" and "fit and worthie to be published".[38] Although written as an apparently verbatim account, the book is not a report of what was actually said at the trial, but instead a reflection on what happened.[39] Nevertheless, Potts "seems to give a generally trustworthy, although not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports".[40]

In his introduction to the trial, Potts writes; "Thus have we for a time left the Graund Witches of the Forrest of Pendle, to the good consideration of a very sufficient jury."[23] Bromley had by then heard the cases against the three Pendle witches who had confessed to their guilt, but he had yet to deal with the others, who maintained their innocence. He knew that the only testimony against them would come from a nine-year-old girl, and that King James had cautioned judges to examine carefully the evidence presented against accused witches, warning against credulity.[7] In his conclusion to the account of the trial, Potts says that it was interposed in the expected sequence "by special order and commandment",[41] presumably of the trial judges. After having convicted and sentenced to death three witches, Bromley may have been keen to avoid any suspicion of credulity by presenting his "masterful exposure" of the evidence presented by Grace Sowerbutts, before turning his attention back to the remainder of the Pendle witches.[7]

Modern interpretation

Potts declares that "this Countie of Lancashire ... now may lawfully bee said to abound asmuch in Witches of divers kinds as Seminaries, Jesuites, and Papists",[42] and describes the three accused women as having once been "obstinate Papists, and now came to Church".[43] The judges would certainly have been keen to be regarded by King James, the head of the judiciary, as having dealt resolutely with Catholic recusants as well as with witchcraft, the "two big threats to Jacobean order in Lancashire".[44] Samlesbury Hall, the family home of the Southworths, was suspected by the authorities of being a refuge for Catholic priests, and it was under secret government surveillance for some considerable time before the trial of 1612.[6] It may be that JP Robert Holden was at least partially motivated in his investigations by a desire to "smoke out its Jesuit chaplain", Christopher Southworth.[34]

The English experience of witchcraft was somewhat different from the continental European one, with only one really mass witchhunt, that of Matthew Hopkins in East Anglia during 1645. That one incident accounted for more than 20 per cent of the number of witches it is estimated were executed in England between the early 15th and mid-18th century, fewer than 500.[45] The English legal system also differed significantly from the inquisitorial model used in other European countries, requiring members of the public to accuse their neighbours of some crime, and for the case to be decided by a jury of their peers. English witch trials of the period "revolved around popular beliefs, according to which the crime of witchcraft was one of ... evil-doing", for which tangible evidence had to be provided.[46]

Potts devotes several pages to a fairly detailed criticism of the evidence presented in Grace Sowerbutts' statement, giving an insight into the discrepancies that existed during the early 17th century between the Protestant establishment's view of witchcraft and the beliefs of the common people, who may have been influenced by the more continental views of Catholic priests such as Christopher Southworth.[48] Unlike their European counterparts, the English Protestant elite believed that witches kept familiars, or companion animals, and so it was not considered credible that the Samlesbury witches had none.[46] Grace's story of the sabbat, too, was unfamiliar to the English at that time, although belief in such secret gatherings of witches was widespread in Europe.[49] Most demonologists of the period, including King James, held that only God could perform miracles, and that he had not given the power to go against the laws of nature to those in league with the Devil.[47] Hence Potts dismisses Sowerbutts' claim that Jennet Bierley transformed herself into a black dog with the comment "I would know by what means any Priest can maintaine this point of Evidence". He equally lightly dismisses Grace's account of the sabbat she claimed to have attended, where she met with "foure black things ... not like men in the face", with the comment that "The Seminarie [priest] mistakes the face for the feete: For Chattox [one of the Pendle witches] and all her fellow witches agree, the Devill is cloven-footed: but Fancie [Chattox's familiar] had a very good face, and was a proper man."[50]

It is perhaps unlikely that the accused women would have failed to draw the examining magistrate's attention to their suspicions concerning Grace Sowerbutts' motivations when first examined, only to do so at the very end of their trial when asked by the judge if they had anything to say in their defence. The trial of the Samlesbury witches in 1612 may have been "largely a piece of anti-Catholic propaganda",[6] or even a "show-trial",[22] the purpose of which was to demonstrate that Lancashire was being purged not only of witches, but also of "popish plotters".[7]

Aftermath

Bromley achieved his desired promotion to the Midlands Circuit in 1616. Potts was given the keepership of Skalme Park by King James in 1615, to breed and train the king's hounds. In 1618 he was given responsibility for "collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years".[51] Jane Southworth's eldest son, Thomas, eventually inherited his grandfather's estate of Samlesbury Hall.[17]

References

Citations

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 22

- Sharpe (2002), p. 1

- Hasted (1993), p. 23

- Hasted (1993), p. 2

- Winzeler (2007), pp. 86–87

- Hasted (1993), pp. 32–33

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 35

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 23

- Martin (2007), p. 96

- Pumfrey (2002), pp. 23–24

- Hasted (1993), p. 5

- Hasted (1993), pp. 8–9

- Hasted (1993), p. 7

- Hasted (1993), p. 30

- Hasted (1993), pp. 30–32

- Davies (1971), p. 94

- Abram (1877), p. 93

- Fields (1998), p. 60

- Bennett (1993), p. 9

- Swain (2002), p. 83

- Bennett (1993), p. 16

- Goodier, Christine, "The Samlesbury Witches", Lancashire County Council, archived from the original on 13 December 2007, retrieved 30 June 2009

- Davies (1971), p. 83

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 24

- Davies (1971), p. 85

- Davies (1971), p. 88

- Davies (1971), p. 86

- Davies (1971), pp. 86–89

- Davies (1971), p. 90

- Davies (1971), p. 93

- Davies (1971), pp. 94–95

- Davies (1971), pp. 100–101

- Hasted (1993), p. 31

- Wilson (2002), p. 139

- Davies (1971), pp. 104–105

- Davies (1971), p. 168

- Davies (1971), p. 106

- Davies (1971), p. xli

- Gibson (2002), p. 48

- Gibson (2002), p. 50

- Davies (1971), p. 107

- Davies (1971), p. 153

- Davies (1971), p. 101

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 31

- Sharpe (2002), p. 3

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 28

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 34

- Sharpe (2002), p. 4

- Wilson (2002), p. 138

- Davies (1971), p. 98

- Pumfrey (2002), p. 38

Bibliography

- Abram, William Alexander (1877), A History of Blackburn, Town and Parish (PDF), retrieved 14 August 2009

- Bennett, Walter (1993), The Pendle Witches, Lancashire County Council Library and Leisure Committee, OCLC 60013737

- Davies, Peter (1971) [1929], The Trial of the Lancaster Witches, London: Frederick Muller, ISBN 978-0-584-10921-4 (Facsimile reprint of Davies' 1929 book, containing the text of The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster by Potts, Thomas (1613))

- Fields, Kenneth (1998), Lancashire Magic and Mystery: Secrets of the Red Rose County, Sigma, ISBN 978-1-85058-606-7

- Gibson, Marion (2002), "Thomas Potts's Dusty Memory: Reconstructing Justice in The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches", in Poole, Robert (ed.), The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, Manchester University Press, pp. 42–57, ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9

- Hasted, Rachel A. C. (1993), The Pendle Witch Trial 1612, Lancashire County Books, ISBN 978-1-871236-23-1

- Martin, Lois (2007), The History of Witchcraft, Pocket Essentials, ISBN 978-1-904048-77-0

- Pumfrey, Stephen (2002), "Potts, plots and politics: James I's Daemonologie and The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches", in Poole, Robert (ed.), The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, Manchester University Press, pp. 22–41, ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9

- Sharpe, James (2002), "The Lancaster witches in historical context", in Poole, Robert (ed.), The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 1–18, ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9

- Swain, John (2002), "Witchcraft, economy and society in the forest of Pendle", in Poole, Robert (ed.), The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, Manchester University Press, pp. 73–87, ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9

- Wilson, Richard (2002), "The pilot's thumb: Macbeth and the Jesuits", in Poole, Robert (ed.), The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories, Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 126–145, ISBN 978-0-7190-6204-9

- Winzeler, Robert L. (2007), Anthropology and religion: what we know, think, and question, Altamira Press, ISBN 978-0-7591-1046-5