San Juan River (Colorado River tributary)

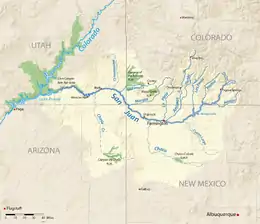

The San Juan River is a major tributary of the Colorado River in the Southwestern United States, providing the chief drainage for the Four Corners region of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona. Originating as snowmelt in the San Juan Mountains (part of the Rocky Mountains) of Colorado, it flows 383 miles (616 km)[2] through the deserts of northern New Mexico and southeastern Utah to join the Colorado River at Glen Canyon.

| San Juan River Są́ bito' (in Navajo) | |

|---|---|

The lower San Juan River, Utah | |

Map of the San Juan River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| States | Colorado, New Mexico, Utah |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | San Juan Mountains |

| • location | Archuleta County, Colorado |

| • coordinates | 37°21′55″N 106°54′02″W[1] |

| • elevation | 7,553 ft (2,302 m) |

| Mouth | Colorado River (Lake Powell) |

• location | San Juan County, Utah |

• coordinates | 37°10′47″N 110°54′03″W[1] |

• elevation | 3,704 ft (1,129 m) |

| Length | 383 mi (616 km)[2] |

| Basin size | 24,649 sq mi (63,840 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Bluff, Utah, about 113.5 mi (182.7 km) from the mouth[4] |

| • average | 2,152 cu ft/s (60.9 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 70,000 cu ft/s (2,000 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Navajo River, Chaco River, Chinle Creek |

| • right | Piedra River, Los Pinos River, Animas River, Mancos River |

The river drains a high, arid region of the Colorado Plateau. Along its length, it is often the only significant source of fresh water for many miles. The San Juan is also one of the muddiest rivers in North America, carrying an average of 25 million US tons (22.6 million t) of silt and sediment each year.[5]

Historically, the San Juan formed the border between the territory of the Navajo in the south and the Ute in the north. Although Europeans explored the Four Corners region as early as the 1700s, it was not settled until the gold and silver booms of the 1860s, when settlers arrived in large numbers from the eastern United States. After heated conflicts over land, the Native Americans were forced into reservations, where their descendants live today.

During the 20th century, intensive drilling in the fossil-fuel rich San Juan Basin and uranium mining along the lower river in Utah generated serious concerns about water quality, particularly in the Navajo Nation where the river is a crucial source of water for irrigation. Runoff from abandoned gold and silver mines has also been a major issue, as occurred in the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill into the Animas River, the main tributary of the San Juan.

The U.S. federal government has built a number of large dams in the San Juan River system to control floods and to provide irrigation and domestic water supply. In addition, the lower part of the river is inundated by Lake Powell, one of the largest reservoirs in the United States. Efficient management is crucial to ensuring enough water supply not just for farms and urban areas but also for recreational boating, fisheries, and environmental restoration. However, heavy water use has significantly reduced the flow of the San Juan River by as much as 25 percent since pre-development conditions. In addition, warming temperatures in the Rocky Mountains are projected to have a further negative effect on snowpack and thus stream flow.

Course

The San Juan River begins in Archuleta County, Colorado at the confluence of its East and West Forks. Both forks originate above elevations of 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in the eastern San Juan Mountains in the San Juan National Forest. The river flows southwest through the foothills of the Rocky Mountains through the town of Pagosa Springs and reaches the Navajo Lake reservoir just north of the New Mexico border, near Arboles, Colorado. Below the Navajo Dam, the San Juan River flows west through a narrow farming valley in the high desert country of the Colorado Plateau. At Farmington, New Mexico, it is joined from the north by its main tributary, the Animas River, which rises in the San Juan Mountains near Silverton, Colorado.[6]

From there it flows west through the Navajo Nation, turning northwest near Shiprock and its namesake monolith, crossing very briefly back into southwest Colorado (within half a mile (0.8 km) of the Four Corners quadripoint) before entering southeastern Utah.[7] West of Bluff, Utah the river slices through the Comb Ridge and enters a series of rugged winding canyons, often over 1,500 feet (460 m) in depth. The lower 70 miles (110 km) of the San Juan River, in a remote portion of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, are flooded by Lake Powell, which is formed by Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River. The San Juan joins the Colorado in San Juan County, Utah at a point about 15 miles (24 km) to the north of Navajo Mountain and 80 miles (130 km) northeast of Page, Arizona.[6]

Tributaries of the upper San Juan River above Navajo Dam include the Rio Blanco and the Navajo River, and the Piedra River and Los Pinos River (Pine River) which join the San Juan in Navajo Lake. In addition to the Animas River, several major tributaries join below Farmington, including the La Plata River and Mancos River in New Mexico, and McElmo Creek in Utah.[6][8] San Juan also has a number of seasonal tributaries that drain arid regions of the Colorado Plateau. These include the Cañon Largo and Chaco River in New Mexico and the Montezuma Creek and Chinle Creek in Utah. The northern tributaries of the San Juan River, which originate in the San Juan Mountains, are snowmelt-driven, with the highest flows between March and June.[9] Southern tributaries such as the Chaco River are mostly ephemeral but can carry large volumes of water during flash floods.[8][10]

Discharge

According to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the average unimpaired runoff or natural flow of the San Juan River basin over the 1906–2014 period was about 2,900 cubic feet per second (82 m3/s), 2,101,000 acre-feet (2.592 km3) per year.[11] The maximum was 6,200 cubic feet per second (180 m3/s), 4,466,000 acre-feet (5.509 km3), in 1941, and the minimum was 710 cubic feet per second (20 m3/s), 513,000 acre-feet (0.633 km3), in 2002.[11] Heavy water use has decreased the river flow considerably since the early 20th century. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) stream gaging station at Bluff, Utah, recorded an average annual discharge of 2,152 cubic feet per second (60.9 m3/s), or 1,559,000 acre-feet (1.923 km3), for the 1915–2013 period.[4] Before the construction of major dams to regulate the river, it sometimes dried up completely in the summer, as it did in 1934 and 1939.[4] The maximum flow was 70,000 cubic feet per second (2,000 m3/s) on September 10, 1927.[4] The great flood of October 1911, which remains the largest recorded flood on the San Juan River, occurred before the USGS began measuring streamflow here. Based on observations of water depth and debris deposits, the 1911 flood may have reached a peak of 148,000 cubic feet per second (4,200 m3/s).[12]

| USGS real-time stations on the San Juan River | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gage location (ID number) |

Start year |

Average discharge |

Maximum discharge |

Minimum discharge |

Drainage area |

Percent of total watershed |

| Pagosa Springs, CO 09342500 |

1935 | 368 ft3/s (10 m3/s) |

25,000 ft3/s (708 m3/s) |

8.3 ft3/s (0.2 m3/s) |

281 mi2 (728 km2) |

1.1% |

| Carracas, CO 09346400 |

1961 | 587 ft3/s (17 m3/s) |

8,590 ft3/s (243 m3/s) |

0.8 ft3/s (0.02 m3/s) |

1,250 mi2 (3,240 km2) |

5.1% |

| Archuleta, NM 09355500 |

1954 | 1,070 ft3/s (30 m3/s) |

18,900 ft3/s (535 m3/s) |

8 ft3/s (0.2 m3/s) |

3,260 mi2 (8,443 km2) |

13.3% |

| Farmington, NM 09365000 |

1931 | 1,980 ft3/s (56 m3/s) |

30,000 ft3/s (849 m3/s) |

27 ft3/s (0.8 m3/s) |

7,240 mi2 (18,750 km2) |

29.4% |

| Shiprock, NM 09368000 |

1935 | 1,983 ft3/s (56 m3/s) |

80,000 ft3/s (2,265 m3/s) |

8 ft3/s (0.2 m3/s) |

12,900 mi2 (33,400 km2) |

52.4% |

| Four Corners, CO 09371010 |

1977 | 1,959 ft3/s (55 m3/s) |

16,900 ft3/s (479 m3/s) |

110 ft3/s (3 m3/s) |

14,600 mi2 (37,800 km2) |

59.3% |

| Bluff, UT 09379500 |

1914 | 2,152 ft3/s (61 m3/s) |

70,000 ft3/s (1,982 m3/s) |

0 ft3/s (0 m3/s) |

23,000 mi2 (59,700 km2) |

93.5% |

| Stations are listed from furthest upstream to furthest downstream. Although river discharge is generally expected to increase from upstream to downstream, note that discrepancies in the data may be due to differences in the period of record, as well as human modifications, diversions, and dams. | ||||||

The San Juan River annual hydrograph exhibits large seasonal variations with the highest monthly flow of 5,267 cubic feet per second (149.1 m3/s) in June, and the lowest of 1,061 cubic feet per second (30.0 m3/s) in December.[4] The completion of Navajo Dam in 1963 and its associated water supply projects have decreased the flow of the river, from about 2,600 cu ft/s (74 m3/s) in the 1914–1963 period[13] to less than 2,000 cubic feet per second (57 m3/s) for the 1964–2016 period,[14] although a minimum release from the dam prevents the river from drying up in the summer.[15] Persistent drought conditions in the 21st century have further reduced the flow of the San Juan River, with an average annual discharge of 1,358 cubic feet per second (38.5 m3/s) or 984,000 acre-feet (1.214 km3) between water years 2000 and 2016.[16]

Geology

The oldest geologic feature of the San Juan River basin is the San Juan Mountains, which consist largely of Precambrian and Paleozoic crystalline rock and outcrops of Tertiary volcanic rock.[17] During the Paleocene and Eocene (about 66–34 million years ago), streams draining off the southern flank of the San Juan Mountains terminated in the San Juan Basin around present-day Farmington, slowly filling it with thick layers of sediment.[18] Over millions of years, the burial of organic material under sedimentary layers created the abundant coal, oil, and natural gas deposits found in the area today.[19]

Fluvial deposits indicate that a stream flowed west across the Colorado Plateau to join the Colorado River at least by the late Miocene (about 5 million years ago).[20] This may have been the ancestral Dolores River, before the uplift of the Ute Mountains diverted it to its present northerly course. When the San Juan Basin filled and overflowed, it formed an outflow channel west into the old Dolores River bed, establishing the San Juan River's modern course.[18]

Though Tectonic forces about 2–3 million years ago caused the terrain to rise across the Monument Upwarp in southeast Utah and northeast Arizona, the river maintained its course as an antecedent stream.[18] The Monument Upwarp consists of a series of parallel anticlines and synclines running generally north to south in an area roughly 90 miles (140 km) long and 35 miles (56 km) wide. Where the river passes through these formations, it has sliced deep canyons through the reddish rock.[21][17] In places, the San Juan has entrenched its ancient meanders thousands of feet into the bedrock, as can be observed in Goosenecks State Park, where it winds 6 miles (9.7 km) through a set of horseshoe bends while traveling a straight-line distance of only 1.5 miles (2.4 km).[22] The canyon cutting was accelerated during the Pleistocene Ice Ages when the climate of the area was much wetter. The wetter climate resulted in floods of up to 1,000,000 cubic feet per second (28,000 m3/s)–ten times larger than any flooding of the San Juan in recorded human history.[23]

The San Juan River flows through highly erodible sedimentary rock–such as sandstone, siltstone, and shale–that make up rock formations such as the slide-prone Chinle Formation. As a result, the San Juan is an extremely muddy river, contributing more than half of the sediment that occurs in the upper Colorado River above Lees Ferry[n 1] despite accounting for only 14 percent of the total runoff.[11]

Between 1914 and 1980, the U.S. Geological Survey station at Bluff, Utah, recorded an average of 25.41 million tons of sediment carried by the San Juan River each year—ranging from 3.24 million tons in 1978 to 112.4 million tons in 1941.[5] The majority of the sediment originates in the watershed downstream of the Animas River.[5]

Since the closure of the Glen Canyon Dam in 1963, sediments have been building a delta in Lake Powell instead of continuing down the Colorado River. Core samples taken in 2011 indicate aggradations up to 89 feet (27 m) thick in the San Juan River arm of Lake Powell.[25]

Watershed

Geography

.jpg.webp)

The San Juan River drains approximately 24,600 square miles (64,000 km2) in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona; the watershed land area is almost the same size as the state of West Virginia. The main stem of the river does not flow through Arizona but comes very close at the Four Corners. The highest point in the San Juan River watershed is 14,091-foot (4,295 m) Windom Peak, located near the headwaters of the Animas River.[26][27] The lowest elevation, where the San Juan River flows into Lake Powell, has a normal maximum elevation of 3,704 feet (1,129 m)[1] but typically fluctuates dozens of feet per year due to seasonal nature of runoff in the Colorado River Basin affecting the reservoir level.[28] Most of the watershed is rural, with some extremely remote, uninhabited areas. About 75 percent of the watershed is shrubland, rangeland, and grassland.[29] Due to the low rainfall and lack of substantial groundwater reserves, agricultural use is scarce, except for river valleys and in higher foothill areas influenced by wetter montane climates. About 2.3 percent of the watershed is dryland farms, and 1.6 percent is irrigated.[30] Forests cover about 20 percent of the watershed, mostly at high elevations.[31]

The San Juan Mountains and Ute Mountains bound the watershed on the north, the Jemez Mountains lie to the east, and various upland and mesa areas of the Colorado Plateau to the south and west. The San Juan Basin is a distinct area of the San Juan River watershed; it is a geologic structural basin known for its abundant fuel resources. The San Juan Basin is roughly coterminous with the southeast quadrant of the San Juan River watershed in northwest New Mexico and southwest Colorado.[32] The watershed as a whole is very arid, with average annual precipitation just shy of 10 inches (250 mm).[31] However, precipitation can be as high as 61 inches (1,500 mm) in the mountains at the headwaters of the San Juan River; a considerable portion of this falls as winter snow.[33] In desert areas, most of the annual precipitation is generated by intense rainstorms during the peak monsoon season of July and August.[27]

Although about 90 percent of the river's water originates as snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado,[34] the largest portion of the watershed – 9,725 square miles (25,190 km2), or 40 percent – lies in New Mexico.[7] A further 23 percent of the watershed is in Colorado, 20 percent is in Arizona, and 17 percent is in Utah.[35] In terms of area drained, the Chaco River is the largest tributary draining 4,510 square miles (11,700 km2), followed by Chinle Creek which drains 4,090 square miles (10,600 km2).[3] The Animas River is the largest tributary in terms of stream flow, but drains a comparatively slim watershed of 1,370 square miles (3,500 km2).[3][8] In the 21st century, the snowpack in the San Juan Mountains has often been diminished by warming winter temperatures which has led to concerns about the long-term water supply for the San Juan River.[36][37] In addition, the mountains are particularly vulnerable to dust storms originating from the Great Basin; dust settling on snowpack increases the absorption of solar energy and often leads to premature melting.[38]

Administration and land use

Well over 50 percent of the San Juan River watershed are Native American lands, the largest being the Navajo Nation, which covers portions of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, in addition to the Jicarilla Apache Nation in New Mexico and the Ute Mountain and Southern Ute Indian Reservations in southwest Colorado.[29] Federal agencies, principally the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service and National Park Service, administer about 25 percent of the watershed. About 13 percent are privately owned (non-Indian) lands, and 3 percent belong to state and local governments.[39]

Protected areas in the watershed include Colorado's Mesa Verde National Park[40] and Canyons of the Ancients National Monument; the Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico,[41] Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona[42] and Bears Ears National Monument in Utah.[43] These parks are all known for their archaeological sites and ancient Native American dwellings. The San Juan National Forest encompasses more than 1.8 million acres (7300 km2) of alpine peaks, pine forests, and desert mesas in the San Juan Mountains;[44] the San Juan watershed includes parts of the South San Juan and Weminuche Wildernesses, the latter being the largest federally designated wilderness in Colorado. Other notable features in the watershed include Shiprock, a nearly 1,600-foot (490 m) high monadnock formation sacred to the Navajo people, and Monument Valley, whose rugged scenery has appeared in many Western films and other media.[45]

The watershed is lightly populated, with most settlements concentrated along the San Juan and Animas Rivers. Farmington, New Mexico is the largest city, with a population of 45,965 at the 2010 census.[46] Other major cities include Durango, Colorado (16,897),[47] Cortez, Colorado (8,482),[48] Shiprock, New Mexico (8,295)[49] and Aztec, New Mexico (6,757).[50] The San Juan Basin supports a large resource extraction economy, with oil, natural gas, coal, helium, alum, clay, fluorspar, uranium and various gemstones as the primary products; historically gold, silver, copper, and lead were also produced in large quantities.[51] As of 2009, the over 40,000 wells in the San Juan Basin had produced more than 42 trillion cubic feet (1.2 trillion m3) of natural gas and 281 million barrels of oil.[52]

History

Indigenous peoples

The San Juan River and its tributaries were an important water source for Native Americans as early as 10,000 BC, when Paleo-Indians inhabited the Four Corners region. By 500 BC–450 AD, the Basketmaker culture was succeeded by the Ancestral Puebloans or Anasazi, who developed distinctive irrigation methods and masonry architecture (pueblos);[53] many ruins and sites are preserved in the San Juan watershed in places such as Mesa Verde National Park.[54] Most settlements were concentrated along the upper San Juan River in New Mexico, where the terrain is gentler and water more abundant. The lower San Juan River in Utah flows through inaccessible canyons that largely precluded habitation.[55] Starting around 1300 AD, a warming climate brought long droughts to the area, forcing the Puebloans to abandon their settlements north of the San Juan River and perhaps eventually causing them to migrate out of the San Juan River basin to the Rio Grande Valley, where their descendants live today.[56]

The Navajo, who continue to live along the San Juan River today, are believed to have migrated into the Four Corners region by the 1500s, and may have come into contact with the last departing Anasazi.[57] The Navajo name for the river was Są́ Bitooh, "Old Age River" or "Old Man's River". Due to its westerly flow, the San Juan is considered a "male river" (Tooh Bikaʼí) and its sacred confluence with the south-flowing Colorado River (the "female river"), in Glen Canyon near Rainbow Bridge, "is the place where clouds and moisture are physically created."[59] The Navajo made offerings to the river to "bless the land with water and provide protection from non-Navajo enemies".[59] The Weminuche Ute, whose homeland was primarily in what is now Colorado, used the San Juan River as their southern boundary with the Navajo. The two groups considered each other enemies.[60]

Spanish colonization and American settlement

The first use of the name Rio San Juan (after San Juan Bautista, the Spanish name for Saint John the Baptist) was apparently by Spanish explorer Juan Rivera, who led an expedition to the area in 1765.[61] Rivera's route would later become part of the Old Spanish Trail between Santa Fe, New Mexico and Southern California. About a decade later, in 1776, the Domínguez–Escalante expedition passed through the San Juan River country, attempting to find a route from Santa Fe to the presidio in Monterey, California. Domínguez and Escalante crossed the San Juan River near where Navajo Lake is today and described the area as having good land suitable for settlement and farming but also "excessively cold even in the months of July and August."[62] The expedition was unsuccessful, turning back at Utah Valley, but their discoveries were crucial in opening up the region to future European settlement.[63]

_BHL39707434.jpg.webp)

Neither Spain nor Mexico established permanent settlements in the San Juan River country due to the harsh winter weather and presence of the native population. In 1848, after the Mexican–American War the area became part of the United States; prospectors arrived in the late 1850s, and upon their discovery of placer gold in tributaries of the upper San Juan River, a gold rush began to the San Juan Mountains. The gold rush reached its peak after the creation of Colorado Territory in 1861, bringing thousands of fortune seekers to this remote region. Silver was discovered along the Animas River in 1871 and led to the growth of present-day Silverton below the area's labor-intensive hard rock mines.[64] The narrow-gauge San Juan Extension of the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (D&RGW) was completed in 1881, linking Durango with the rest of the D&RGW system at Alamosa, Colorado via tracks through the upper San Juan River canyon.[65]

The rapidly rising number of settlers faced conflicts with Ute and Navajo Indians. In 1863, the U.S. Army under General James Henry Carleton, in response to the "Navajo problem", forcibly evicted almost 10,000 Navajo from their lands near the San Juan River. More than 2,000 people died of starvation and disease during and after the 300-mile (480 km) "Long Walk" to Fort Sumner, New Mexico.[66] However, the Navajo were allowed to return to much of their original lands in 1868, and a federally recognized reservation was established south of the San Juan River.[67] The Utes, who had been granted a reservation in western Colorado in 1868, faced hostility with settlers because most of the area's mineral wealth was concentrated on Ute lands. The U.S. Army drove the last of the Utes from southwest Colorado by 1881 (with the exception of a small portion in the Southern Ute Reservation, established by the Brunot Agreement in 1873) and the following year 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) of land were opened up for ranching, farming, and prospecting.[68]

An unintended consequence of the Indian wars was how they shaped future water rights in the San Juan River system. When the Navajo reservation was established in 1868, it implicitly included water rights, which were formally acknowledged when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Winters v. United States (1908) that a federally established Indian reservation was "entitled to the water needed to create a permanent homeland."[69] In 2005 the state of New Mexico reached a settlement with the Navajo Nation, where the Navajo finally secured their claim to over 600,000 acre-feet (0.74 km3) of San Juan River water.[70] Due to the prior appropriation doctrine, the Navajo now possess the best water rights to the San Juan River. In Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner writes: "The Indians, where water was concerned, clearly had the upper hand. The white man's cavalry had made beggars of them; now his courts had made them kings."[71]

The lower San Juan River country remained a remote backwater well into the late 19th century; John Wesley Powell's famed 1869 expedition down the Colorado River barely noted the San Juan River where they passed it in Glen Canyon.[72] During the 1875 Hayden Survey of the lower San Juan River, George B. Chittenden wrote: "This whole portion of the country is now and must ever remain utterly worthless. It has no timber, very little grass, and no water."[73][74] However, in 1879 more than 200 Mormon pioneers embarked on the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition which established the agricultural settlement of Bluff, Utah on the lower San Juan River in April 1880. The wagon trail they established became an important link between Utah Territory and the Four Corners region (although the infamously difficult Hole-in-the-Rock crossing just above the mouth of the San Juan was moved upstream to Halls Crossing the following year).[75][76] The colony suffered greatly in its early years due to a series of floods, but the settlers persisted, as the LDS church strongly wished to maintain its presence in southeast Utah.[77] In 1882, oil prospector E. L. Goodridge conducted the first known exploration of the lower San Juan canyons, floating from Bluff to Lee's Ferry, Arizona.[78] Later, placer gold was discovered along the river, which brought more than 2,000 miners to Bluff in the 1890s in what proved to be a short-lived boom.[79]

20th century

In October 1911, heavy monsoon rains generated the largest flood ever recorded on the San Juan River, causing severe damage along the entire length of the river and many of its tributaries. More than 100 bridges and 300 miles (480 km) of railroad tracks were destroyed in the Colorado part of the river basin alone, completely cutting off transport and communications. Along the Animas River, "virtually all the crops" were destroyed.[80] On the lower river, most of Bluff was inundated and 1,000 acres (400 ha) of farmland was swept away. At Mexican Hat, Utah the Goodridge bridge, whose deck was 39 feet (12 m) above the river, was destroyed, indicating the floodwaters were at least that deep.[81]

Farmington, the largest city on the San Juan River and in the Four Corners region, was established in 1901 and grew significantly in the 1920s as coal, oil, and natural gas were discovered in the area.[82] Uranium was discovered in the Bluff area in the 1940s, and became a major source for the US nuclear program during World War II and afterward for domestic nuclear plants.[83] As a consequence of the uranium boom, over 500 mining waste disposal sites continue to contaminate the San Juan River and local groundwater. One of the most polluted sites (at the former Shiprock, New Mexico mill) exhibits considerable leakage into the river.[84] Oil spills have also contaminated the San Juan River at times; one of the largest occurred in October 1972 when over 4.5 million gallons (1 million liters) of oil leaked into the San Juan River from a broken pipeline.[85]

The gold and silver industry began to decline in the 1950s, leaving behind hundreds of abandoned mines that have contributed to acid mine drainage problems. Rail traffic along the San Juan River declined with the closure of mines, although it was revived briefly in the 1960s by a temporary rise in oil production. When Navajo Dam was built along the upper San Juan River, it flooded the towns of Rosa and Arboles as well as a large portion of the D&RGW San Juan Line through the river canyon. The federal government paid for the cost of relocating the line, which began operating in August 1962; however, this section along the San Juan River was abandoned barely five years later due to falling traffic. (The section of the San Juan Line east of Chama has been preserved as the Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad, and the section from Durango to Silverton as the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad.)[86]

In 2015, one of the worst environmental disasters in Colorado and New Mexico's history occurred when the Gold King Mine near Silverton experienced a massive wastewater spill. The accident occurred when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was attempting to drain contaminated water that had built up at the mine entrance. More than 3 million gallons (11,400 m3) of highly acidic waste spilled into the Animas and San Juan Rivers, turning the water a bright yellow-orange color. The spill temporarily threatened irrigation and domestic water supply as far downstream as the Navajo Nation and contaminated sediment with heavy metals, including lead and zinc.[88][89] The EPA asserted it would take "full responsibility" for the spill.[90]

Dams and water projects

As early as 2,000 years ago, the Anasazi were known to build dams and sophisticated irrigation systems on tributaries of the San Juan River to irrigate their crops. During the initial period of European settlement in the 1800s, small private dams were built to supply water to farms and mining operations and to generate hydroelectricity (an early hydro project was the Tacoma power station, built on the Animas River in 1905.)[91] In 1901, the Turley survey concluded that the San Juan River contained enough water to irrigate up to 1,300,000 acres (530,000 ha), but due to the high cost of delivering water to desert lands, neither private investors nor the federal government were willing to fund such large projects.[92] The U.S. Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) conducted surveys of dam sites on the lower San Juan River in 1914, as part of the Boulder Canyon Project (the so-called "Bluff reservoir" was never built, after engineers determined that the high silt load of the lower San Juan would make a storage reservoir here useless within a short time).[93][94] By the 1920s – with the oil boom spurring rapid growth in the Farmington area and food shortages impacting the Navajo Nation – the federal government recognized the need for a multi-purpose dam project on the upper San Juan River, which would later become Navajo Dam.

The big water projects in the San Juan River basin were mostly built by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation after the 1950s as participating units of the Colorado River Storage Project, whose aim was to regulate the water supply of the upper Colorado River system, control floods and generate power. Navajo Dam, completed in 1963 after five years of construction, impounds 1.7 million acre feet (2.1 km3) of water in Navajo Lake. The dam serves for flood control, irrigation and long-term water storage, and its operations are paired with two major water projects of the upper San Juan River: the San Juan–Chama Project which diverts almost 100,000 acre-feet (0.12 km3) per year from the San Juan watershed to the Rio Grande system serving Albuquerque, New Mexico,[95] and the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project which provides water for 63,900 acres (25,900 ha) of farmland on the Navajo Nation.[96] These two projects together were designed to put to "beneficial use" the water allocated to New Mexico under the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divided the waters of the Colorado River and its tributaries between the seven U.S. states that make up the Colorado River Basin.[97]

Today, a total of 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of land are irrigated in the San Juan watershed, supplied by a combination of federal and local agencies.[4] Other federal reclamation projects in the San Juan watershed are the Pine River Project, consisting of Vallecito Dam and Lake on the Los Pinos River;[98] the Florida Project with Lemon Dam and Reservoir on the Florida River;[99] and the Hammond Project along the San Juan River below Navajo Dam.[100] The Dolores Project diverts water from the Dolores River to serve farmers in the San Juan watershed, near Cortez, Colorado.[101] The most recently completed project is the Animas-La Plata Water Project near Durango, which had been authorized as early as 1968,[102] but was not completed until 2013.[103] Originally intended as an irrigation project, it was redesigned to provide domestic and industrial water supply.[104] Currently under construction is the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project, which intends to convey water 280 miles (450 km) south from Navajo Lake to parts of the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache Nation as far as Gallup, New Mexico.[105][106]

River ecology

The San Juan River provides habitat for at least eight native fish species – cutthroat trout, roundtail chub, speckled dace, flannelmouth sucker, bluehead sucker, mottled sculpin, Colorado pikeminnow, and razorback sucker, with a possible ninth, bonytail chub.[8] The latter three are considered endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and are rarely found in the San Juan River today, if at all. With the exception of trout and dace, which inhabit clear, cold mountain streams in the headwaters, the native fishes are mostly adapted to the warm, shallow and silty characteristics of the lower San Juan.[8] The San Juan cutthroat trout, a unique lineage of cutthroat trout endemic to the river and its tributaries, was considered extinct until its rediscovery in 2018.[107] In addition, about 23 non-native fish species have been introduced to the San Juan River watershed. The common carp and channel catfish have become widespread in the lower reaches of the San Juan River.[8] In the "tailwater" reach below Navajo Dam, introduced rainbow and brown trout thrive in the cold and stable flows released from the dam.[8] Rainbow and brown trout have also proliferated in the headwaters of the San Juan River above Navajo Lake.[108]

Native fish species in the San Juan River reproduce during high spring runoff events, which historically would overflow the banks of the river and spread out into the riparian zone, creating off-channel spawning habitat.[9] Since the completion of the Navajo Dam, the portion of the San Juan River between the dam and Farmington became unsuitable for native fish due to the reduction in seasonal fluctuations.[109] However, at Farmington the San Juan is joined by the Animas River – which is not controlled by any major dams – and regains some of its seasonal characteristics.[9] In addition, the impoundment of water at Navajo Dam does not appear to have a significant effect on the amount of sediment transported in the river; thus, the aquatic environment of the lower San Juan, though somewhat degraded, still resembles pre-development conditions.[9][110]

The Bureau of Reclamation consulted with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service between 1991 and 1997 to develop operation criteria at Navajo Dam that would comply with the Endangered Species Act. Since 1999, Navajo Dam releases have been changed to approximate the historic seasonal hydrograph of the San Juan River rather than a stable flow year-round. The San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program requires spring peak releases of 5,000 cubic feet per second (140 m3/s), dependent on water availability, and a reduction of the summer base flow from 500 cubic feet per second (14 m3/s) to 250 cubic feet per second (7.1 m3/s), to mimic historic dry season conditions. The peak release from Navajo Dam is timed to match the peak of snowmelt runoff on the Animas River.[9] The program also includes other restoration and remediation work, such as improving fish passage at diversion dams, removing obsolete diversion structures, and eradicating non-native species such as catfish.[8][111]

Recreation

The San Juan is a popular recreational river, despite some parts of its course being remote. Near the headwaters, Pagosa Springs, Colorado is known for its natural hot springs on the banks of the San Juan River.[112] In the foothills, the 15,600-acre (6,300 ha) Navajo Lake is one of the largest bodies of water in both Colorado and New Mexico. Navajo State Park in Colorado and Navajo Lake State Park in New Mexico provide boating, water-skiing, fishing, and shoreline camping; two marinas are located in the New Mexico portion of the lake.[113][114] The 6 miles (9.7 km) of river from below Navajo Dam to Gobernador Wash are known as one of the best trout fishing waters in the United States due to the cold, clear flows released from the base of the dam.[115] Cutthroat, rainbow and brown trout are present in this section of the San Juan River.[9] Although trout are present in another 13 miles (21 km) further downstream to Cañon Largo, the fishery is diminished in quality due to rising amounts of sediment.[116] These "Quality Waters" of the San Juan River are visited by well over 50,000 anglers each year.

The section of the river between Farmington and Bluff which flows through Navajo lands is administered by the Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation Department, which issues permits for hiking and camping. However, it is seldom visited by boaters due to a lack of good river access sites. The lower San Juan River below Bluff is used heavily for whitewater boating and rafting, especially below the Sand Island river access, which (as of 2006) sees about 11,165 users per year. Many boaters take out at Mexican Hat, about 20 miles (32 km) down the river, although some continue through the lower canyons to Clay Hills, near the head of Lake Powell, 56 miles (90 km) further downstream. Commercial trips operate mainly during the late spring-early summer snowmelt season, though the season can be extended significantly in wet years. Applications for private trips are approved by the Bureau of Land Management's Monticello Field Office via lottery; about 900 spots are awarded each year out of more than 4000 requests. The section between Mexican Hat and Clay Hills is characterized by moderate class II-III rapids.[118] Below Clay Hills, the San Juan flows through very isolated country to Lake Powell, where a long flat-water paddle is required to reach the closest services at Dangling Rope Marina.[118]

See also

References

- "San Juan River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1979-12-31. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed March 21, 2011

- "Boundary Descriptions and Names of Regions, Subregions, Accounting Units and Cataloging Units". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "USGS Gage #09379500 San Juan River near Bluff, Utah: Water-Data Report 2013" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2013. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Characteristics of Suspended Sediment in the San Juan River near Bluff, Utah" (PDF). Water Resources Investigations 82-4104. U.S. Geological Survey. 1982. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- USGS Topo Maps for United States (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. ACME Mapper. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "A Description of the San Juan Watershed". New Mexico Environment Department. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Gido, Keith B.; Propst, David L. (2012). "Long-Term Dynamics of Native and Nonnative Fishes in the San Juan River, New Mexico and Utah, under a Partially Managed Flow Regime" (PDF). Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 141 (645–659): 645–659. doi:10.1080/00028487.2012.683471. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Section 19 Alluvial Valley Floors" (PDF). Pinabete Permit Application Package. U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Colorado River Basin Natural Flow and Salt Data, 1906-2014". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2016-11-30. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Orchard, Kenneth Lynn (2001). "Paleoflood hydrology of the San Juan River, southeastern Utah, USA". University of Arizona. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "USGS Gage #09379500 San Juan River near Bluff, Utah: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1914–1963. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "USGS Gage #09379500 San Juan River near Bluff, Utah: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1964–2016. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Recommendations for San Juan River Operations and Administration for 2013 through 2016" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "USGS Gage #09379500 San Juan River near Bluff, Utah: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2000–2016. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 9.

- Rabbitt et al. 1969, p. 108.

- Dubiel, R.F. (2013). "Geology, Sequence Stratigraphy, and Oil and Gas Assessment of the Lewis Shale Total Petroleum System, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Rabbitt et al. 1969, p. 106.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 27–28.

- "Welcome to Goosenecks State Park". Utah State Parks. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 31.

- Weisheit, John (ed.). "A Colorado River Sediment Inventory" (PDF). Colorado Plateau River Guides. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Hornewer, N.J. (2014). "Sediment and Water Chemistry of the San Juan River and Escalante River Deltas of Lake Powell, Utah, 2010–2011" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Windom Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 1978-10-13. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 7.

- "Water Operations: Historic Data". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 23.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 25.

- Benke & Cushing 2011, p. 533.

- "Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of theSan Juan Basin Province of New Mexico and Colorado" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Nov 2002. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Upper San Juan Watershed Rapid Assessment". USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. May 2010. Retrieved 2017-05-16. The page lists all completed watershed assessments for the State of Colorado. The Upper San Juan and other watershed assessments are available as downloadable PDFs.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 11.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 24.

- Streater, Scott (2009-01-22). "New study details effects of soot pollution on snowpack, water supply in West". E&E News. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "New study: Dust, warming portend dry future for the Colorado River". Phys.org. 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Dust Accelerates Snow Melt in San Juan Mountains". NASA Earth Observatory. 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 23–24.

- "Mesa Verde National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Chaco Culture National Historic Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Canyon de Chelly National Monument". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Bears Ears National Monument". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "San Juan National Forest: About the Forest". U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Perrottet, Tony (Feb 2010). "Behind the Scenes in Monument Valley: The vast Navajo tribal park on the border of Utah and New Mexico stars in Hollywood movies but remains largely hidden to visitors". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Farmington, New Mexico". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Durango, Colorado". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Cortez, Colorado". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Shiprock, New Mexico". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- "Aztec, New Mexico". QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Bieberman, Robert A.; Clarich, Mona (1951). "Mineral Resources of the San Juan Basin" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "The San Juan Basin, a Complex Giant Gas Field, New Mexico and Colorado". 58th Annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, Durango, Colorado. American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Jun 2010. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 60–61.

- Gibbon & Ames 1998, p. 512.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 34.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 63.

- McPherson, Robert S. "Navajo Indians". Utah History to Go. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 93–94.

- Simmons 2011, p. 22.

- Simmons 2011, p. 46.

- Crutchfield 2016, p. 5–7.

- Alexander, Thomas G. "Dominguez-Escalante Expedition". Utah History to Go. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- "Chapter 6: Early Mining and Transportation in Southwestern Colorado 1860–1881". Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- Glover, Vernon J. (2011). "Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, San Juan Extension, Wolf Creek Trestle" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 6. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

- Burnett, John (2005-06-15). "The Navajo Nation's Own 'Trail of Tears'". NPR. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "Treaty Between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians: Proclaimed August 12, 1868". Judicial Branch of the Navajo Nation. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Chapter 5: The Utes in Southwestern Colorado: A Confrontation of Cultures". Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Leeper, John W. "Avoiding a Train Wreck in the San Juan River Basin". Southern Illinois University. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- "Executive Summary of the San Juan River Basin in New Mexico: Navajo Nation Water Rights Settlement" (PDF). New Mexico Office of the State Engineer. 2005-04-19. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Reisner 1986, p. 271.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 22.

- Aton & McPherson 2000, p. 40.

- Hayden 1875, p. 361.

- Reeve, W. Paul (Aug 1995). "Hole-In-The-Rock Trek Remains an Epic Experience in Pioneering". Utah History to Go. Retrieved 2017-05-14.

- Miller, David E. (1973). "Hole-in-the-rock expedition" (PDF). New Mexico Geological Society. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Gregory & Thorpe 1938, p. 33.

- Gregory & Thorpe 1938, p. 2.

- Gregory & Thorpe 1938, p. 34.

- Butler, Ann (2011-10-09). "Durango's worst flood ever: Southwest Colorado was cut off by 1911 deluge" (PDF). Durango Herald. riversimulator.org. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Webb, Leake & Turner 2007, p. 73.

- "History of Farmington". City of Farmington, New Mexico. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Ringholz, Raye C. "Utah's Uranium Boom". Utah Division of State History. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Quinones, Manuel (2011-12-13). "As Cold War abuses linger, Navajo Nation faces new mining push". E&E News. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Melancon, Michaud & Thomas 1979, p. 26.

- Wilson & Pfarner 2012, pp. 14–17.

- "Emergency Response to August 2015 Release from Gold King Mine". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Kellogg, Joshua (2015-08-16). "Animas, San Juan rivers reopen from toxic mine spill". The Farmington Daily Times. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Ellis, Ralph (2015-08-13). "EPA chief says agency 'takes full responsibility' for Animas River spill". CNN. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "A powerful piece of history: Tacoma hydroelectric plant producing green energy for 100-plus years". Durango Herald. 2011-09-09. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- Glaser, Leah (1998). "Navajo Indian Irrigation Project" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- La Rue 1916, p. 213.

- Eighteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service, 1918-1919. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1919.

- "San Juan-Chama Project" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Navajo Indian Irrigation Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Navajo Irrigation, San Juan-Chama Diversion". Government Documents on Native American Water Rights in Arizona. University of Arizona Libraries. 1958-07-09. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Pine River Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Florida Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Hammond Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Voggesser, Garrit (2001). "The Dolores Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Animas-La Plata Project: Implementation of the Colorado Ute Settlement Act Amendments of 2000". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2007-01-11. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Animas-La Plata Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Animas-La Plata Project Water Supply and Demand Study" (PDF). Colorado Water Conservation Board. 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2017-03-17. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Project History" (PDF). Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Mar 2007. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Colorado biologists rediscover fish long thought to be extinct — then rescue them as wildfire advances". The Denver Post. 2018-09-06. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- White, Jim. "San Juan River, Pagosa Springs: Fish Survey and Management Information" (PDF). Colorado Parks & Wildlife. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Lamarra, Vincent A. (Feb 2007). "San Juan River Fishes Response to Thermal Modification" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Thompson, Kendall R. (1982). "Characteristics of Suspended Sediment in the San Juan River near Bluff, Utah" (PDF). Water-Resources Investigations 82-4104. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-15.

- "San Juan Recovery Implementation Program". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Paul & Wambach 2012, p. 54.

- "Navajo Lake State Park". New Mexico State Parks. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Navajo State Park". Colorado Parks & Wildlife. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- Wethington, C. Marc; Wilkinson, Peter (Sep 2005). "Management Plan for the San Juan River, 2004-2008" (PDF). New Mexico Department of Game and Fish. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Animas-La Plata Project Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 2". U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 1996. p. C-10. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- "Mexican Hat to Clay Hills Crossing (Lower San Juan)". American Whitewater. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

Works cited

- Aton, James M.; McPherson, Robert S. (2000). River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 1-45718-080-4.

- Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E. (2011). Rivers of North America. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08045-418-4.

- Crutchfield, James (2016). It Happened in Colorado. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-49302-352-3.

- Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998). Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-81530-725-X.

- Gregory, Herbert E.; Thorpe, Malcolm R. (1938). The San Juan Country: A Geographic and Geologic Reconnaissance of Southeastern Utah. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Hayden, Ferdinand Vandeveer (1875). Ninth Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey, of the Territories embracing Colorado and Parts of Adjacent Territories. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- La Rue, Eugene Clyde (1916). Colorado River and its Utilization. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Melancon, Susan M.; Michaud, Terry S.; Thomas, Robert William (Nov 1979). Assessment of Energy Resource Development Impact on Water Quality: The San Juan River Basin. Las Vegas: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- Paul, Susan Joy; Wambach, Carl (2012). Touring Colorado Hot Springs. Falcon Guides. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-76278-568-1.

- Rabbitt, Mary C.; McKee, Edwin D.; Hunt, Charles B.; Leopold, Luna B. (1969). The Colorado River Region and John Wesley Powell: A collection of papers honoring Powell on the 100th anniversary of his exploration of the Colorado River, 1869–1969. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Reisner, Marc (1986). Cadillac Desert. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-19927-3.

- Simmons, Virginia McConnell (2011). The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado and New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-45710-989-8.

- Webb, Robert H.; Leake, S.A.; Turner, Raymond M. (2007). The Ribbon of Green: Change in Riparian Vegetation in the Southwestern United States. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-81652-588-1.

- Wilson, Spencer; Pfarner, Wes (2012). Saving the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61423-579-8.

External links

- San Juan River Flow Data

- San Juan River Rafting

- San Juan River Water Information Program

- Navajo Lake water levels