Tanis

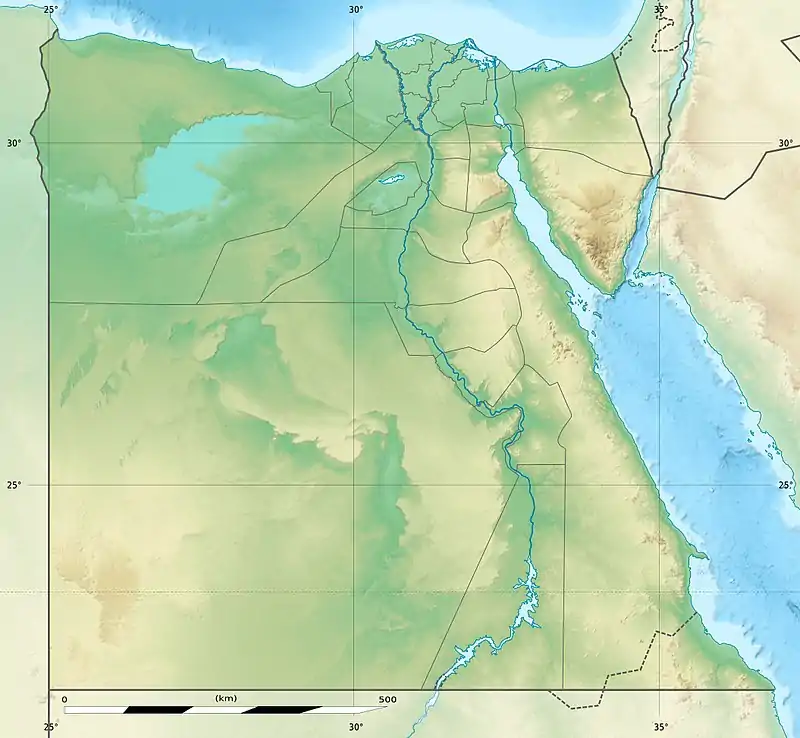

Tanis (Ancient Greek: Τάνις or Τανέως /ˈteɪnɪs/ TAY-niss[1][2][3]) or San al-Hagar (Arabic: صان الحجر, romanized: Ṣān al-Ḥaǧar; Ancient Egyptian: ḏꜥn.t [ˈcʼuʕnat];[4] Akkadian: URUṣa-aʾ-nu;[5] Coptic: ϫⲁⲛⲓ or ϫⲁⲁⲛⲉ or ϫⲁⲛⲏ;[6][7] Hebrew: צֹועַן Ṣōꜥan [Zoan]) is the Greek name for ancient Egyptian ḏꜥn.t, an important archaeological site in the north-eastern Nile Delta of Egypt, and the location of a city of the same name. It is located on the Tanitic branch of the Nile, which has long since silted up. The first study of Tanis dates to 1798 during Napoléon Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt. Engineer Pierre Jacotin drew up a map of the site in the Description de l'Égypte. It was first excavated in 1825 by Jean-Jacques Rifaud, who discovered the two pink granite sphinxes now in the Musée du Louvre, and then by François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette between 1860 and 1864, and subsequently by William Matthew Flinders Petrie from 1883 to 1886. The work was taken over by Pierre Montet from 1929 to 1956, who discovered the royal necropolis dating to the Third Intermediate Period in 1939. The Mission française des fouilles de Tanis (MFFT) has been studying the site since 1965 under the direction of Jean Yoyotte and Philippe Brissaud, and François Leclère since 2013.

Tanis

ϫⲁⲛⲓ ϫⲁⲛⲏ ϫⲁⲁⲛⲉ San al-Hagar صان الحجر | |

|---|---|

The ruins of Tanis today | |

Tanis | |

| Coordinates: 30°58′37″N 31°52′48″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Sharqia |

Today, the main parts of the temple dedicated to Amun-Ra can still be distinguished by the presence of large obelisks that marked the various pylons as in other Egyptian temples. Now fallen to the ground and lying in a single direction, they may have been knocked down by a violent earthquake during the Byzantine era. They form one of the most notable aspects of the Tanis site. Archaeologists have counted more than twenty. This accumulation of remnants from different epochs contributed to the confusion of the first archaeologists who saw in Tanis the biblical city of Zoan in which the Hebrews would have suffered pharaonic slavery. Pierre Montet, in inaugurating his great excavation campaigns in the 1930s, began from the same premise. He was hoping to discover traces that would confirm the accounts of the Old Testament. His own excavations gradually overturned this hypothesis, even if he was defending this biblical connection until the end of his life. It was not until the discovery of Qantir/Pi-Ramesses and the resumption of excavations under Jean Yoyotte that the place of Tanis was finally restored in the long chronology of the sites of the delta.

History

| Djanet (ḏꜥn(t))[8][6] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tanis is unattested before the 19th Dynasty of Egypt, when it was the capital of the 14th nome of Lower Egypt.[9][lower-alpha 1] A temple inscription datable to the reign of Ramesses II mentions a "Field of Tanis", while the city in se is securely attested in two 20th Dynasty documents: the Onomasticon of Amenope and the Story of Wenamun, as the home place of the pharaoh-to-be Smendes.[11]: 921

The earliest known Tanite buildings are datable to the 21st Dynasty. Although some monuments found at Tanis are datable earlier than the 21st Dynasty, most of these were in fact brought there from nearby cities, mainly from the previous capital of Pi-Ramesses, for reuse.[12] Indeed, at the end of the New Kingdom the royal residence of Pi-Ramesses was abandoned because the Pelusiac branch of the Nile in the Delta became silted up and its harbour consequently became unusable.[11]: 922

After Pi-Ramesses' abandonment, Tanis became the seat of power of the pharaohs of the 21st Dynasty, and later of the 22nd Dynasty (along with Bubastis).[9][12] The rulers of these two dynasties supported their legitimacy as rulers of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt with traditional titles and building works, although they pale compared to those at the height of the New Kingdom.[13] A remarkable achievement of these kings was the building and subsequent expansions of the Great temple of Amun-Ra at Tanis (at the time, Amun-Ra replaced Seth as the main deity of the eastern Delta), while minor temples were dedicated to Mut and Khonsu whom, along with Amun-Ra, formed the Theban Triad.[12] The intentional emulation towards Thebes is further stressed by the fact that these gods bore their original Theban epithets, leading to Thebes being more commonly mentioned than Tanis itself.[11]: 922 Furthermore, the new royal necropolis at Tanis successfully replaced the one in the Theban Valley of the Kings.[12]

After the 22nd Dynasty Tanis lost its status of royal residence, but became in turn the capital of the 19th nome of Lower Egypt. Starting from the 30th Dynasty, Tanis experienced a new phase of building development which endured during the Ptolemaic Period.[11]: 922 It remained populated until its abandonment in Roman times.[9]

In Late Antiquity, it was the seat of the bishops of Tanis, who adhered to the Coptic Orthodox Church.[14]

By the time of John of Nikiû in the 7th century, Tanis appears to have already declined significantly, as it was grouped together with four other towns under a single prefect.[15]

The 1885 Census of Egypt recorded San el-Hagar as a nahiyah in the district of Arine in Sharqia Governorate; at that time, the population of the city was 1,569 (794 men and 775 women).[16]

Ruins

Though Tanis was briefly explored in the early 19th century, the first large-scale archaeological excavations there were made by Auguste Mariette in the 1860s.[17] In 1866, Karl Richard Lepsius discovered a copy of the Canopus Decree, an inscription in both Greek and Egyptian, at Tanis. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, discovered 67 years earlier, this inscription included a full hieroglyphic text, thus allowing a direct comparison of the Greek text to the hieroglyphs and confirming the accuracy of Jean-François Champollion's approach to deciphering hieroglyphs.[18]

During the subsequent century the French carried out several excavation campaigns directed by Pierre Montet, then by Jean Yoyotte and subsequently by Philippe Brissaud.[11]: 921 For some time the overwhelming amount of monuments bearing the cartouches of Ramesses II or Merenptah led archaeologists to believe that Tanis and Pi-Ramesses were in fact the same. Furthermore, the discovery of the Year 400 Stela at Tanis led to the speculation that Tanis should also be identified with the older, former Hyksos capital, Avaris. The later re-discovery of the actual, neighbouring archaeological sites of Pi-Ramesses (Qantir) and Avaris (Tell el-Dab'a) made clear that the earlier identifications were incorrect, and that all the Ramesside and pre-Ramesside monuments at Tanis were in fact brought here from Pi-Ramesses or other cities.[11]: 921–2

There are ruins of a number of temples, including the chief temple dedicated to Amun, and a very important royal necropolis of the Third Intermediate Period (which contains the only known intact royal pharaonic burials, the tomb of Tutankhamun having been entered in antiquity). The burials of three pharaohs of the 21st and 22nd Dynasties – Psusennes I, Amenemope and Shoshenq II – survived the depredations of tomb robbers throughout antiquity. They were discovered intact in 1939 and 1940 by Pierre Montet and proved to contain a large catalogue of gold, jewelry, lapis lazuli and other precious stones, as well as the funerary masks of these kings.

The chief deities of Tanis were Amun; his consort, Mut; and their child Khonsu, forming the Tanite triad. This triad was, however, identical to that of Thebes, leading many scholars to speak of Tanis as the "northern Thebes".

In 2009, the Egyptian Culture Ministry reported archaeologists had discovered a sacred lake in the temple of Mut at Tanis. The lake, built out of limestone blocks, had been 15 meters long and 5 meters deep. It was discovered 12 meters below ground in good condition. The lake could have been built during the late 25th–early 26th Dynasty.[19]

In 2011, analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery, led by archaeologist Sarah Parcak of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, found numerous related mud-brick walls, streets, and large residences, amounting to an entire city plan, in an area that appears blank under normal images.[20][21] A French archeological team selected a site from the imagery and confirmed mud-brick structures approximately 30 cm below the surface.[22] However, the assertion that the technology showed 17 pyramids was denounced as "completely wrong" by the Minister of State for Antiquities at the time, Zahi Hawass.[23]

Cultural references

The Biblical story of Moses being found in the marshes of the Nile River (Book of Exodus, Exodus 2:3–5) is often set at Tanis,[24] which is often identified with Zoan (Hebrew: צֹועַן Ṣōʕan).

In the 1981 Indiana Jones film Raiders of the Lost Ark, Tanis is fictitiously portrayed as a lost city which was buried in antiquity by a massive sandstorm, before being rediscovered by a Nazi expedition looking for the Ark of the Covenant.[25]

The Tanis fossil site, which may preserve unique remains from the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, is named after the city. The paleontologist Robert de Palma chose the name based on the significance of Tanis in the decipherment of hieroglyphs, as well as its role in Raiders of the Lost Ark as the hiding place of the Ark of the Covenant.[26]

Gallery

Wendjebauendjed's funerary mask

Wendjebauendjed's funerary mask Wendjebauendjed's cups from Tanis

Wendjebauendjed's cups from Tanis Pharaoh Osorkon II's tomb at Tanis

Pharaoh Osorkon II's tomb at Tanis The gold funerary mask of Psusennes I

The gold funerary mask of Psusennes I

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian towns and cities

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

- List of historical capitals of Egypt

Notes

- Biblical archaeologist Benjamin Mazar believed that the Year 400 Stela, found in Tanis and datable to the 13th century BC, can be an evidence that the site had some settlement in the 18th or 17th century BC.[10]

References

- "Tanis". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Tanis". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Tanis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Loprieno, Antonio (1995). Ancient Egyptian: A linguistic introduction. pp. 39, 245.

- "Oracc RINAP Ashurbanipal 011".

- Gauthier, Henri (1929). Dictionnaire des noms géographiques contenus dans les textes hiéroglyphiques Vol. 6. p. 111.

- Vycichl, W. (1983). Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte, p. 328.

- Wallis Budge, E. A. (1920). An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary: with an index of English words, king list and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, Coptic and Semitic alphabets, etc. Vol II. John Murray. p. 1064.

- Snape, Steven (2014). The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-500-77240-9.

- Benjamin Mazar, Encyclopedia Miqrait, "Eretz Yisrael", p. 682

- Bard, Kathryn A., ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-98283-5.

- Robins, Gay (1997). The Art of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. pp. 195–197. ISBN 0714109886.

- De Mieroop, Marc Van (2007). A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 400. ISBN 9781405160711.

- Siméon Vailhé, "Tanis", in The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 14. (Robert Appleton Company, 1912).

- Maspero, Jean; Wiet, Gaston (1919). Matériaux pour servir à la géographie de l'Égypte. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. p. 116.

- Egypt min. of finance, census dept (1885). Recensement général de l'Égypte. p. 289. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Graham, Geoffrey. "Tanis". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. p. 350.

- Parkinson, Richard. Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment. pp. 19–20, 42.

- Bossone, Andrew. 'Sacred Lake' found in Delta. Egypt Independent, October 15, 2009.

- "Space Archaeology - Street plan of Tanis".

- Tucker, Abigail. "Space Archaeologist Sarah Parcak Uses Satellites to Uncover Ancient Egyptian Ruins". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Pringle, Heather Satellite Imagery Uncovers Up to 17 Lost Egyptian Pyramids 27 May 2011

- Theodoulou, Michael (May 29, 2011). "Idea of 17 hidden pyramids is 'wrong'". The National. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- Lindsay Falvey (2013). "Musing on Agri-History". Asian Agri-History 17(2), p. 184.

- Handwerk, Brian (21 January 2017). ""Lost City" of Tanis". National Geographic.

- Mitchell, Alanna (May 19, 2019). "Why this stunning dinosaur fossil discovery has scientists stomping mad". Maclean's.

Bibliography

- Association française d’Action artistique. 1987. Tanis: L’Or des pharaons. (Paris): Ministère des Affaires Étrangères and Association française d’Action artistique.

- Brissaud, Phillipe. 1996. "Tanis: The Golden Cemetery". In Royal Cities of the Biblical World, edited by Joan Goodnick Westenholz. Jerusalem: Bible Lands Museum. 110–149.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson. [1996]. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). 3rd ed. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited.

- Loth, Marc, 2014. "Tanis – 'Thebes of the North’“. In "Egyptian Antiquities from the Eastern Nile Delta", Museums in the Nile Delta, Vol. 2, ser. ed. by Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl, and Faye Kalloniatis. Cairo/Berlin: Opaion. ISBN 9783000453182

- Montet, Jean Pierre Marie. 1947. La nécropole royale de Tanis. Volume 1: Les constructions et le tombeau d’Osorkon II à Tanis. Fouilles de Tanis, ser. ed. Jean Pierre Marie Montet. Paris: .

- ———. 1951. La nécropole royale de Tanis. Volume 2: Les constructions et le tombeau de Psousennès à Tanis. Fouilles de Tanis, ser. ed. Jean Pierre Marie Montet. Paris: .

- ———. 1960. La nécropole royale de Tanis. Volume 3: Les constructions et le tombeau de Chechanq III à Tanis. Fouilles de Tanis, ser. ed. Jean Pierre Marie Montet. Paris.

- Stierlin, Henri, and Christiane Ziegler. 1987. Tanis: Trésors des Pharaons. (Fribourg): Seuil.

- Yoyotte, Jean. 1999. "The Treasures of Tanis". In The Treasures of the Egyptian Museum, edited by Francesco Tiradritti. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. 302–333.