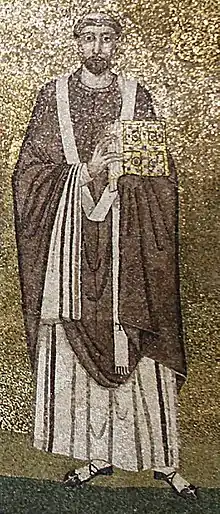

Pope Symmachus

Pope Symmachus (died 19 July 514) was the bishop of Rome from 22 November 498 to his death.[1] His tenure was marked by a serious schism over who was elected pope by a majority of the Roman clergy.[1]

Symmachus | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

| |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 22 November 498 |

| Papacy ended | 19 July 514 |

| Predecessor | Anastasius II |

| Successor | Hormisdas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | |

| Died | 19 July 514 Rome, Ostrogothic Kingdom |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 19 July |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

Early life

He was born on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia (then under Vandal rule), the son of Fortunatus; Jeffrey Richards notes that he was born a pagan, and "perhaps the rankest outsider" of all the Ostrogothic Popes, most of whom were members of aristocratic families.[2] Symmachus was baptised in Rome, where he became Archdeacon of the Roman Church under Pope Anastasius II (496–498).

Papacy

Symmachus was elected pope on 22 November 498[3] in the Constantinian basilica (Saint John Lateran). The archpriest of Santa Prassede, Laurentius, was elected pope on the same day at the Basilica of Saint Mary (presumably Saint Mary Major) by a dissenting faction with Byzantine sympathies, who were supported by Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius. Both factions agreed to allow the Gothic King Theodoric the Great to arbitrate. He ruled that the one who was elected first and[4] whose supporters were the most numerous should be recognized as pope. This was a purely political decision. An investigation favored Symmachus and his election was recognized as proper.[5] However, an early document known as the "Laurentian Fragment" claims that Symmachus obtained the decision by paying bribes,[6] while deacon Magnus Felix Ennodius of Milan later wrote that 400 solidi were distributed amongst influential personages, whom it would be indiscreet to name.[7]

Roman Synod I

Symmachus proceeded to call a synod, to be held at Rome on 1 March 499, which was attended by 72 bishops and all of the Roman clergy. Laurentius attended this synod. Afterwards he was assigned the diocesis of Nuceria in Campania. According to the account in the Liber Pontificalis, Symmachus bestowed the See on Laurentius "guided by sympathy", but the "Laurentian Fragment" states that Laurentius "was severely threatened and cajoled, and forcibly despatched" to Nuceria (now Nocera Inferiore, in the Province of Salerno).[8] The synod also ordained that any cleric who sought to gain votes for a successor to the papacy during the lifetime of the pope, or who called conferences and held consultations for that purpose, should be deposed and excommunicated.[9]

Ariminum Synod II

In 501, the Senator Rufius Postumius Festus,[10] a supporter of Laurentius, accused Symmachus of various crimes. The initial charge was that Symmachus celebrated Easter on the wrong date. The king Theodoric summoned him to Ariminum to respond to the charge. The pope arrived only to discover a number of other charges, including unchastity and the misuse of church property, would also be brought against him.[11][12] Symmachus panicked, fleeing from Ariminum in the middle of the night with only one companion. His flight proved to be a miscalculation, as it was regarded as an admission of guilt. Laurentius was brought back to Rome by his supporters, but a sizeable group of the clergy, including most of the most senior clerics, withdrew from communion with him. A visiting bishop, Peter of Altinum,[13] was appointed by Theodoric to celebrate Easter 502 and assume the administration of the See, pending the decision of a synod to be convened following Easter.[14]

Presided over by the other Italian metropolitans, Peter II of Ravenna, Laurentius of Milan, and Marcellianus of Aquileia, the synod opened in the Basilica of Santa Maria (Maggiore). It proved tumultuous. The session quickly deadlocked over the presence of a visiting bishop, Peter of Altina, who had been sent by Theoderic as Apostolic Visitor, at the request of Senators Festus and Probinus, the opponents of Symmachus.[15] Symmachus argued that the presence of a visiting bishop implied the See of Rome was vacant, and the See could only be vacant if he were guilty—which meant the case had already been decided before the evidence could be heard. Although the majority of the assembled bishops agreed with this, the Apostolic Visitor could not be made to withdraw without Theodoric's permission; this was not forthcoming. In response to this deadlock, rioting by the citizens of Rome increased, causing a number of bishops to flee Rome and the rest to petition Theodoric to move the synod to Ravenna.

Roman Synod III

King Theodoric refused their request to move the synod, ordering them instead to reconvene on 1 September. On 27 August the King wrote to the bishops that he was sending two of the Majores Domus nostrae, Gudila and Bedeulphus, to see to it that the synod assembled in safety and without fear.[16] Upon reconvening, matters were no less acrimonious. First the accusers introduced a document which included a clause stating that the king already knew Symmachus was guilty, and thus the synod should assume guilt, hear the evidence, then pass sentence. More momentous was an attack by a mob on Pope Symmachus' party as he set out to make his appearance at the Synod: many of his supporters were injured and several—including the priests Gordianus and Dignissimus—killed. Symmachus retreated to St. Peter's and refused to come out, despite the urgings of deputations from the synod.[17] The "Life of Symmachus", however, presents these killings as part of the street-fighting between the supporters of Senators Festus and Probinus on the one side, and Senator Faustus on the other. The attacks were directed particularly against clerics, including Dignissimus, a priest of San Pietro in Vincoli, and Gordianus, a priest of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, though the rhetoric of the passage extends the violence to anyone who was a supporter of Symmachus, man or woman, cleric or layperson. It was unsafe for a cleric to walk about in Rome at night.[18]

Palmaris Synod IV

At this point, the synod petitioned king Theodoric once again, asking permission to dissolve the meeting and return home. Theodoric replied, in a letter dated 1 October, that they must see the matter to a conclusion. So the bishops assembled once again on 23 October 502 at a place known as Palma,[19] and after reviewing the events of the previous two sessions decided that since the pope was the successor of Peter the Apostle, they could not pass judgment on him, and left the matter to God to decide. All who had abandoned communion with him were urged to reconcile with him, and that any clergy who celebrated mass in Rome without his consent in the future should be punished as a schismatic. The resolutions were signed by 76 bishops, led by Laurentius of Milan and Peter of Ravenna.[20]

End of papacy

Despite the outcome of the synod, Laurentius returned to Rome, and for the next four years, according to the "Laurentian Fragment", he held its churches and ruled as pope with the support of the senator Festus.[21] The struggle between the two factions was carried out on two fronts. One was through mob violence committed by supporters of each religious camp, and it is vividly described in the Liber Pontificalis.[22] The other was through diplomacy, which produced a sheaf of forged documents, the so-called "Symmachian forgeries", of judgments in ecclesiastical law to support Symmachus' claim that as pope he could not be called to account.[23] The forgeries are speculated to have emerged during the Roman Synod III and served to provide the conclusion provided at Palmaris.[24] A more productive achievement on the diplomatic front was to convince king Theodoric to intervene, conducted chiefly by two non-Roman supporters, the Milanese deacon Ennodius and the exiled deacon Dioscorus. At last Theodoric withdrew his support of Laurentius in 506, instructing Festus to hand over the Roman churches to Symmachus.[25]

In 513, Caesarius, bishop of Arles, visited Symmachus while being detained in Italy. This meeting led to Caesarius' receiving a pallium. Based on this introduction, Caesarius later wrote to Symmachus for help with establishing his authority, which Symmachus eagerly gave, according to William Klingshirn, "to gather outside support for his primacy."[26]

Pope Symmachus provided money and clothing to the Catholic bishops of Africa and Sardinia who had been exiled by the rulers of the Arian Vandals. He also ransomed prisoners from upper Italy, and gave them gifts of aid.[27]

Despite Laurentius being classed as an antipope, it is his portrait that continues to hang in the papal gallery in the Church of St. Paul's, not that of Symmachus.[28]

Death

Symmachus died on 19 July 514,[3] and was buried in St. Peter's Basilica. He had ruled for fifteen years, seven months, and twenty-seven days.

References

- Kirsch 1913.

- Richards 1979, p. 243.

- Hughes, Philip (1947). A History of the Church. Vol. 1. Sheed & Ward. p. 319. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 201: The Latin text of the Life of Symmachus says vel, not et: that is to say 'or', not 'and'.

- Davis 2000, p. 43f; The original Latin in Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 301: quod tandem aequitas in Symmacho invenit, et cognitio veritatis

- Davis 2000, p. 97.

- Richards 1979, p. 70f.

- Davis 2000, p. 44, 97; Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 204; Hefele 1895, p. 59: Nuceria had been destroyed, probably by the Visigoths, at the beginning of the fifth century. Laurentius was being sent to a ruin, to care for refugees.

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 231: …si presbyter, aut diaconus, aut clericus, papa incolumi, et eo inconsulto, aut subscriptionem pro Romano pontificatu commodare, aut pitacia promittere, aut sacramentum praebere tentaverit, aut aliquod certe suffragium pollicere, vel de hac causa privatis conventiculis factis deliberare atque decernere, loci sui dignitate atque communione privetur

- Jones & Martindale 1980, pp. 467–469.

- Davis 2000, p. 98: The "Laurentian Fragment" states that, while walking along the seashore, he saw the woman with whom he was accused of committing sin

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 284; Hefele 1895, p. 60: Deacon Ennodius of Pavia, later the city's Bishop, who drew up an apology for Symmachus, admits the charge of adultery

- Altinum, a town on the shore of the Lagoon of Venice, had been sacked and burned by Attila the Hun in A.D. 452. The scattered survivors retreated to the islands in the lagoon.

- Richards 1979, p. 71.

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 201, "Life of Symmachus"

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, pp. 254–256.

- Richards 1979, p. 72.

- Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 202.

- Hefele 1895, p. 67: a porticu Beati Petri Apostoli, quae appellatur ad Palmaria

- Richards 1979, p. 73; Mansi, Labbe & Martin 1762, p. 261–269.

- Davis 2000, p. 98.

- Richards 1979, p. 75.

- Richards 1979, p. 81f.

- Townsend 1933, pp. 172–74.

- Richards 1979, p. 76.

- Klingshirn 1994, p. 30, 86f; Several letters between the two survive, which Klingshirn has translated, pp. 88–94

- Davis 2000, p. 46.

- Demacopoulos 2013, p. 115.

Bibliography

- Davis, Raymond (2000), The Book of Pontiffs (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of the First Ninety Roman Bishops to AD 715, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-0-85323-545-3

- Demacopoulos, George E. (2013), The Invention of Peter: Apostolic Discourse and Papal Authority in Late Antiquity, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-4517-2, pp. 103–116.

- Hefele, Charles Joseph (1895), A History of the Councils of the Church, from the Original Documents, translated by W. Clark, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark

- Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Martindale, John Robert (1980), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: A.D. 395–527, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-20159-9

- Kennell, S. A. H. (2000), Magnus Felix Ennodius: A Gentleman of the Church, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-10917-3

- Kirsch, Johann Peter (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Klingshirn, William E. (1994), Caesarius of Arles: Life, Testament, Letters, Glasgow: Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-0-85323-368-8 pp. 87–96.

- Sessa, Kristina (2011), The Formation of Papal Authority in Late Antique Italy: Roman Bishops and the Domestic Sphere, Cambridge University Press, pp. 208–246, ISBN 978-1-139-50459-1

- Mansi, Giovanni Domenico; Labbe, Philippe; Martin, Jean Baptiste (1762), Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, vol. 8, Florence: Antonius Zatta

- Moorhead, John (1978), "The Laurentian Schism: East and West in the Roman Church", Church History, 47 (2): 125–136, doi:10.2307/3164729, JSTOR 3164729, S2CID 162650963

- Onnis, Omar; Mureddu, Manuelle (2019). Illustres. Vita, morte e miracoli di quaranta personalità sarde (in Italian). Sestu: Domus de Janas. ISBN 978-88-97084-90-7. OCLC 1124656644.

- Townsend, W. T. (1933), "The so-called Symmachan forgeries", Journal of Religion, 13 (2): 165–174, doi:10.1086/481294, JSTOR 1196859, S2CID 170343707

- Richards, Jeffrey (1979), The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476–752, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-7100-0098-9

- Wirbelauer, Eckhard (1993), Zwei Päpste in Rom: der Konflikt zwischen Laurentius und Symmachus (498–514) : Studien und Texte, Munchen: Tuduv, ISBN 978-3-88073-492-0

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.