Santo Tomas Internment Camp

Santo Tomas Internment Camp, also known as the Manila Internment Camp, was the largest of several camps in the Philippines in which the Japanese interned enemy civilians, mostly Americans, in World War II. The campus of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila was utilized for the camp, which housed more than 3,000 internees from January 1942 until February 1945. Conditions for the internees deteriorated during the war and by the time of the liberation of the camp by the U.S. Army many of the internees were near death from lack of food.

| Santo Tomas Internment Camp | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

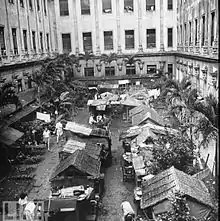

One of the principal buildings housing internees at Santo Tomas was the Education building (now UST Hospital building). Shanties and vegetable gardens can be seen near the building and the wall of the University compound is in the background. | |

.svg.png.webp) Santo Tomas Internment Camp Location of Santo Tomas Internment Camp in the Philippines | |

| Coordinates | 14°36′36″N 120°59′22″E |

| Other names | Manila Internment Camp |

| Location | University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Japanese-occupied Philippines |

| Commandant | Lt. Col. Toshio Hayashi |

| Original use | University of Santo Tomas campus |

| Operational | January 1942 – February 1945 |

| Number of inmates | more than 3,000 internees |

| Liberated by | U.S. Army |

| Notable inmates | List

|

Background

Japan attacked the Philippines on December 8, 1941, the same day as its raid on Pearl Harbor (on the Asian side of the International Date Line). American fighter aircraft were on patrol to meet an expected attack, but ground fog delayed the Japanese aircraft on Formosa. When the attack finally came, most of the American air force was caught on the ground, and destroyed by Japanese bombers. On the same day, the Japanese invaded several locations in northern Luzon and advanced rapidly southward toward Manila, capital and largest city of the Philippines. The U.S. army, consisting of about 20,000 Americans and 80,000 Filipinos, retreated onto the Bataan Peninsula. On December 26, 1941, Manila was declared an open city and all American military forces abandoned the city leaving civilians behind. On January 2, 1942, Japanese forces entered and occupied Manila. They ordered all Americans and British citizens to remain in their homes until they could be registered.[1] On January 5, the Japanese published a warning in the Manila newspapers. "Any one who inflicts, or attempts to inflict, an injury upon Japanese soldiers or individuals shall be shot to death." But if the assailant could not be found the Japanese "would hold ten influential persons as hostages."[2]

On May 6, 1942, Gen. Jonathan Wainwright who took over the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) after Gen. Douglas MacArthur's departure, surrendered the remaining forces on Corregidor to the Japanese. This was followed a few days later by the USAFFE units in Visayas and Mindanao. There were a few exceptions who took to the forests and mountains to initiate guerrilla warfare against the Japanese occupiers. It was the worst defeat of the United States in World War II.[3]

Establishment of the internment camp

Over a period of several days, the Japanese occupiers of Manila collected all enemy aliens in Manila and transported them to the University of Santo Tomas, a walled compound 19.5 hectares (48 acres) in size.[4] Thousands of people, mostly Americans and British, staked out living and sleeping quarters for themselves and their families in the buildings of the University. The Japanese mostly let the foreigners fend for themselves except for appointing room monitors and ordering a 7:30 p.m. roll call every night. The Japanese selected a business executive named Earl Carroll as head of the internee government and he selected five, later nine, men he knew to serve as an executive committee.[5] They appointed a British missionary who had lived in Japan, Ernest Stanley, as interpreter. Santo Tomas quickly became a "miniature city." The internees created several committees to manage affairs, including a police force, set up a hospital with the abundant medical personnel available, and began providing morning and evening meals to more than 1,000 internees who did not have food or money to buy it.[6]

Thousands of Filipinos and non-interned foreigners from neutral countries gathered around the fenced compound every day and passed food, money, letters, and other goods across the fence to the internees. The Japanese put a stop to that by ordering the fence to be shielded by bamboo mats but they permitted parcels to enter the compound after being searched. However, the loose Japanese control of the camp had teeth. Two young Englishmen and an Australian who escaped from the camp were captured, beaten, tortured, and executed on February 15. Carroll, Stanley, and the monitors of the two rooms where the men had been accommodated were forced to watch.[7] Thereafter, no escapes from Santo Tomas, which would have been relatively easy given the small size of the Japanese guard force, were recorded.

Carroll and the Executive Committee reported to the Japanese commandant of the camp. In the early days of STIC, as it was called by internees, the Japanese did not provide food so it was purchased with loans from the Red Cross and donations from individuals.[8] The Committee did a delicate dance with the Japanese attempting to moderate Japanese orders while following a "policy of close and voluntary cooperation … to secure liberties" and "to retain the greatest degree of self government possible."[9] The cooperation of the internees permitted the Japanese to control the camp with a minimum of resources and personnel, amounting at times to only 17 administrators and 8 guards.[10]

Internees

The number of internees in February 1942 amounted to 3,200 Americans, 900 British (including Canadian, Australian, and other Commonwealth people), 40 Poles, 30 Dutch, and individuals from Spain, Mexico, Nicaragua, Cuba, Russia, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, China, and Burma. About 100 of the total were Filipino or part-Filipino,[11] principally the spouses and children of Americans. Of the Americans, 2,000 were males and 1,200 females, including 450 married couples. Children numbered 400. At least one Japanese was interned, Yurie Hori Riley, married to American Henry D. Riley, along with their children.[12] Seventy African-Americans were among the internees as were two American Indians, a Mohawk and a Cherokee. The British were divided about equally between male and female. The imbalance in gender among the Americans was primarily due to the fact that, anticipating the war, many wives and children of American men employed in the Philippines had returned to the US before December 8, 1941.[13] A few people had been sent to the Philippines from China to escape the war in that country.[14] Some had arrived only days before the Japanese attack.

The internees were diverse: business executives, mining engineers, bankers, plantation owners, seamen, shoemakers, waiters, beachcombers, prostitutes, retired soldiers from the Spanish–American War, 40 years earlier, missionaries, and others. Some came into the camp with their pockets full of money and numerous friends on the outside; others had only the clothes on their backs.[15]

During the war, a total of about 7,000 people were resident in Santo Tomas. There was a regular flow of people in and out of the camp, as some missionaries, elderly, and sick people were initially allowed to live outside the camp and more than 2,000 were transferred to Los Baños internment camp. About 150 internees were repatriated to their home countries as part of prisoner exchange agreements between Japan and the United States and the United Kingdom. Most internees, however, served a full 37 months in captivity.[16]

The Japanese segregated the internees by sex. Thirty to 50 people were crowded into small classrooms in university buildings. The allotment of space for each individual was between 1.5 and 2 square metres (16 to 22 square feet). Bathrooms were scarce. Twelve hundred men living in the main building had 13 toilets and 12 showers.[17] Lines were normal for toilets and meals. Internees with money were able to buy food and built huts, "shanties," of bamboo and palm fronds in open ground where they could take refuge during the day, although the Japanese insisted that all internees sleep in their assigned rooms at night. Soon there were several hundred shanties and their owners constituted a "camp aristocracy." The Japanese attempted to enforce a ban on sex, marriage, and displays of affection among the internees. They often complained to the Executive Committee about "inappropriate" relations between men and women in the shanties.[18]

The biggest problem for the internees was sanitation. The Sanitation and Health Committee had more than 600 internee men working for it. Their tasks included building more toilets and showers, laundry, dishwashing, and cooking facilities, disposal of garbage, and controlling the flies, mosquitoes, and rats that infested the compound.[19] During the first two years of imprisonment conditions for the internees were tolerable with no serious outbreaks of disease, malnutrition, or other symptoms of poor conditions.

At first, most internees believed that their imprisonment would only last a few weeks, anticipating that the United States would quickly defeat Japan. As news of the surrender of American forces at Bataan and Corregidor seeped into the camp, the internees settled in for a long stay.[20]

Internee government

The internees petitioned the Japanese for the right to elect their leadership and on July 27, 1942, an election was held. Earl Carroll declined to be a candidate. After the votes were counted, the Japanese exercised their prerogative by announcing that Carroll C. Grinnell, who had placed sixth in the election, was appointed as the chairman of a seven-person executive committee.[21] Grinnell, a business executive, would be the leader of the internees for the duration of the war. Grinnell's leadership was controversial. He appeared to many of the internees to be too authoritative in ruling them and too acquiescent to the Japanese, banning community dances, building a recreational shack for the Japanese guards, and setting up an internee court and jail for offenders.[22] Dave Harvey, the most popular entertainer in the camp, satirized the Grinnell government by saying he was going to write a book titled "Mine Camp" and dedicate it to Grinnell.[23]

Transfer to Los Baños

Santo Tomas became increasingly crowded as internees from outlying camps and islands were transferred into the camp. With the population in Santo Tomas approaching 5,000, the Japanese on May 9, 1943, announced that 800 men would be transferred to a new camp, Los Banos, 37 miles (68 km) distant, the then campus of the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture, now part of University of the Philippines Los Baños.[24] On May 14, the 800 men were loaded on trains and left Santo Tomas. In succeeding months, more men and families were transferred to Los Baños including a large number of missionaries and clergymen who were previously allowed to remain outside the internment camps provided they pledged not to engage in politics. Described as a "delightful spot" on arrival, conditions at Los Baños became increasingly crowded and difficult toward the end of the war, mirroring the situation at Santo Tomas.[25] The population of Los Baños totaled 2,132, including a three-day-old baby, when it was liberated by American soldiers and Filipino guerrillas on February 23, 1945.[26]

Worsening conditions

As the war in the Pacific turned against Japan, living conditions in Santo Tomas became worse and Japanese rule over the internees more oppressive. Prices inflated on soap, toilet paper, and meat as the supply diminished at camp markets and stores. Those without money mostly went without food, although a fund for destitute internees was established. Meat began to disappear from the communal kitchens in August 1943 and by the end of the year there was no meat at all.[27]

A blow to internee living standards was a typhoon on November 14, 1943, which dumped 69 cm (27 inches) of rain on the compound, destroying many of the shanties, flooding buildings and destroying much-needed food and other supplies. The distress caused by the typhoon, however, was soon relieved by the receipt in the camp of Red Cross food parcels just before Christmas. Every internee, including children, received a parcel weighing 48 pounds (21.8 kg) and containing luxuries such as butter, chocolate, and canned meat. Vital medicine, vitamins, surgical instruments, and soap were also received. These were the only Red Cross parcels received by the internees during the war and undoubtedly staved off malnutrition and disease, reducing the death rate in Santo Tomas. For internees (and U.S. military prisoners of war) in the Philippines this was the only aid received during the war. More parcels were not received because the Japanese linked prisoner and internee exchanges with Red Cross aid to internees. American officials such as J. Edgar Hoover of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and General Douglas MacArthur objected to proposed prisoner exchanges and the Japanese refused to allow more aid to be delivered without such exchanges.[28]

In February 1944, the Japanese army took over direct control of the camp and dismissed the civilian administrators. Armed guards patrolled the perimeter of the camp and contacts with the outside world for supplies were terminated. The food ration the Japanese provided for internees was 1,500 calories per person per day, less than the modern-day recommendation of 2,000 calories.[29] The Japanese abolished the Executive Committee and appointed Grinnell, Carroll and an Englishman, S. L. Lloyd, as "agents of the internees" and liaison officers with the Japanese.

Food shortages became steadily more serious throughout 1944. After July 1944, "the food at the camps became extremely inadequate, weight loss, weakness, edema, paresthesia and beriberi were experienced by most adults." Internees ate insects and wild plants, but the internee government declared it illegal for internees to pick weeds for personal, rather than community, use. One internee was jailed by the internee police for 15 days for harvesting pigweed. Some of the hardship could have been alleviated had the Japanese allowed the camp to accept food donations from local charities or permitted internee men working outside the camp to forage for wild plants and fruit.[30]

Gardens, both private and community, for food had been planted shortly after the internees arrived at Santo Tomas and, to combat the growing food shortages, the Japanese captors demanded that the internees grow more food for themselves, although the internees, on a 1,100 calorie per day ration by November 1944 were less capable of hard labor.[31]

In January 1945, a doctor reported that the average loss of weight among male internees had been 24 kg (53 pounds) during the three years at Santo Tomas, 32.5% of average body weight. (40% loss of normal body weight will usually result in death.)[32] That month, eight deaths among internees were attributed to malnutrition, but Japanese officials demanded that the death certificates be altered to eliminate malnutrition and starvation as causes of death. On January 30, four additional deaths occurred. That same day the Japanese confiscated much of the food left in the camp for their soldiers and the "cold fear of death" gripped the weakened internees.[33] The Japanese were preparing for a last-ditch battle with American forces advancing on Manila.

From January 1942 until March 1945, 390 total deaths from all causes in Santo Tomas were recorded, a death rate about three times that of the United States in the 1940s. People over 60 years old were the most vulnerable. They comprised 18% of the total population, but suffered 64% of deaths.[34]

Arrival of the American Army

The Santo Tomas internees began to hear news of American military action near the Philippines in August 1944. Clandestine radios in the camp enabled them to keep track of major events. On September 21 came the first American air raid in the Manila area.[35] American forces invaded the Philippine Island of Leyte on October 20, 1944, and advanced on Japanese forces occupying other islands in the country. American airplanes began to bomb Manila on a daily basis.

On December 23, 1944, the Japanese arrested Grinnell and three other camp leaders for unknown reasons. Speculation was that they were arrested because they were in contact with Filipino soldiers and guerrilla resistance forces and the "Miss U" spy network. On January 5, the four men were removed from the camp by Japanese military police. Their fate was unknown until February when their bodies were found. They had been executed.[36]

The U.S. rushed to liberate the prisoner of war and internee camps in the Philippines due to a common belief that the Japanese would massacre all their prisoners, military and civilian.[37] A small American force pushed rapidly forward and, on February 3, 1945, at 8:40 p.m., internees heard the sound of tanks, grenades, and rifle fire near the front wall of Santo Tomas. Five American tanks from the 44th Tank Battalion broke through the fence of the compound.[38] The Japanese soldiers took refuge in the large, three-story Education Building, taking 200 internees hostage, including internee leader Earl Carroll, and interpreter Ernest Stanley. Carroll and Stanley were ordered to accompany several Japanese soldiers to a meeting with American forces to negotiate a safe passage for the Japanese out of Santo Tomas in exchange for a release of their 200 hostages. During the meeting between the Americans, Filipinos and Japanese, a Japanese officer named Abiko reached into a pouch on his back, apparently for a hand grenade, and an American soldier shot and wounded him. Abiko was especially hated by the internees. He was carried away by a mob of enraged internees, kicked and slashed with knives, and thrown out of a hospital bed onto the floor.[39] He died a few hours later.[39]

Ernest Stanley

In the words of an American military officer, the British missionary of the "Two by Twos" Ernest Stanley was "the most hated man in camp." He "spoke Japanese fluently. Always in the company of the Japanese, he spoke to none of the prisoners during all the years of incarceration. On the eve of the liberation, he conversed and laughed with everyone, including high-ranking American Army officers. Speculation arose that he was either a spy or a member of British intelligence."[40]

Stanley became the essential mediator in the negotiations between the Japanese in the Education Building of Santo Tomas and the American forces ringing the building and compound. His negotiation efforts initially failed, and American tanks bombarded the building, first warning the hostages within to take cover. Several internees and Japanese were killed and wounded. The next day, February 4, Stanley, going back and forth between Americans and Japanese, negotiated an agreement by which the 47 Japanese soldiers in the building would release their hostages but retain their arms and be escorted by the Americans 1st Cavalry Division led by 1st Lieutenant Burt Kennedy to Malacanang Palace thinking it was still in Japanese hands.[41] Stanley led the Japanese out of the building and accompanied them to their place of release, an event recorded by a photograph that appeared in Life magazine.[42]

The formation was getting lost, and upon reaching Legarda Street near present day Nagtahan Flyover, the Japanese prison guards headed by Col. Toshio Hayashi, were ambushed by Filipino guerrillas. The angry crowd joined in later and 63 Japanese troops were killed.[43]

After the liberation

The total number of internees liberated at Santo Tomas was 3,785, of which 2,870 were Americans and most of the remainder were British.[44]

The American force that liberated the internees at Santo Tomas was small in numbers,[45] and the Japanese still had soldiers near the compound. Fighting went on for several days. The internees received food and medical treatment but were not allowed to leave Santo Tomas. Registration of them for return to their countries of origin began. On February 7, General Douglas MacArthur visited the compound, an event that was accompanied by Japanese shelling. That night and again on February 10, 28 people in the compound were killed in the artillery barrage, including 16 internees.[46]

The evacuation of the internees began on February 11. Sixty-four U.S. Army and Navy nurses interned in Santo Tomas were the first to leave that day and board airplanes for the United States. Flights and ships to the United States for most internees began on February 22.[47] Although food became adequate with the arrival of American soldiers, life continued to be difficult. The lingering effects of near-starvation for so many months saw 48 people die in the camp in February, the highest death total for any month. Most internees could not leave the camp because of a lack of housing in Manila. The American military pressured all American internees to return to the U.S., including long-time residents and mixed-blood families who wished to remain in the Philippines. Tensions between the remaining internees and the American military were high. Slowly, in March and April 1945 the camp emptied out, but it was not until September that Santo Tomas finally closed and the last internees boarded a ship for the U.S. or sought out places to live in Manila, almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Manila.[48]

Collaborators with the Japanese

American intelligence investigated and detained about 50 internees suspected of being collaborators or spies for the Japanese. Most were cleared, but a few, although repatriated, had their cases referred to the FBI.[49] Ernest Stanley, the interpreter, was reportedly investigated, but cleared of charges. He later went to Japan as an employee of the U.S. Army and became a Japanese citizen. He married a Japanese woman and took up residence in Tokyo and adopted a son. He lived in Tokyo the rest of his life.[42]

Earl Carroll defended himself and other camp leaders from allegations of collaboration in a series of newspaper articles in which he claimed the internees had waged a "secret war" against the Japanese. That view was generally accepted by Americans, and most internees were given a campaign ribbon for "contributing materially to the success of the Philippine campaign." Carroll and (posthumously) Grinnell received the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian decoration of the U.S. government.[50]

Scholars have characterized the cooperation between the Japanese and the internees at Santo Tomas as "legitimate collaboration. By working with the internees, the Japanese suppressed resistance, isolated Americans from Filipinos, freed up resources, and exploited the camp for intelligence and propaganda. In return the camp obtained greater autonomy, security, and a higher standard of living."[51]

Notable internees

- Beulah Ream Allen (along with her 2 children), medical doctor[52]

- Roy Anthony Cutaran Bennett[53]: 329

- Frank Buckles, shipping company employee and last known surviving World War I U.S. military service member.[54]

- Laura M. Cobb, U.S. Navy nurse[55]

- William Henry Donald, advisor to Chiang Kai-shek[53]: 545

- Adolph Daniel Edward Elmer, botanist[56]

- A. V. H. Hartendorp, journalist and author[53]: 511

- Carl Mydans, photographer[57]

- Shelley Smith Mydans, journalist[57]

- Josephine Nesbit, U.S. Army nurse[58]

- Yay Panlilio, journalist, American/Filipina guerrilla leader.

- Horace Bristol Pond, businessman

- Evelyn Witthoff, medical doctor[53]: 528

- Carl Mydans and Shelley Mydans husband and wife photojournalist employed by Time and Life magazines, who took some of the most iconic photos of World War II.

- Virginia Hewlett wife of Frank Hewlett, reporter for United Press[59]

See also

References

- Morton, Louis. "VIII–XIV". U.S. Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific: The Fall of the Philippines. US Army in World War. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Morton, pp.237–238

- Bell, Walter F. Philippines in World War Two, 1941–1945. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999, p. 1.

- "Liberation Newsletter" Santo Tomas Documents". Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Hartendorp, A.V.H. The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines. Manila: Bookmark, 1967, pp. 10, 14

- Pratt, Caroline Bailey, ed. Only a Matter of Days: The World War II Prison Camp Diary of Fay Cook Bailey. Bennington, VT: Merriam Press, 2006, pp. 32–33

- Hartendorp, p. 90

- Hartendorp, p. 24–25

- Ward, James Mace. "Legitimate Collaboration: the Administration of Santo Tomas Internment Camp and its Histories, 1942–2003". Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 77, No 2, 2008, p. 166

- Ward, 192

- For example, Roy Anthony Cutaran Bennett, who had an American father and a Filipina mother.

- "US-Japan Dialogue on POWs". www.us-japandialogueonpows.org.

- Hartendorp, 11

- Van Sickle, Emily. The Iron Gates of Santo Tomas. Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1992, p. 21

- Van Sickle, p. 22

- Hartendorp, xiii, ff.

- Hartendorp, 50

- Hartendorp, p. 359–361

- Hartendorp, p. 26–27

- Van Sickle, pp 39–40

- Hartendorp, p. 162

- Ward, 168

- Ward, 174. The reference is to Adolf Hitler's book, Mein Kampf

- McCall, James E. Santo Tomas Internment Camp: STIC in Verse and Reverse, STIC-toons and STIC-stistics. Lincoln, NE: Woodruff Printing, 1945, p. 64

- Beaber, Herman. "Diary of a POW. Deliverance has come…". Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- Cogan, Frances B. Captured: The Japanese Internment of American Civilians in the Philippines, 1941–1945. Athens, GA: U of GA Press, 2000 p. 307

- Van Sickle, p.181

- Cogan, pg. 183–185

- Van Sickle, pp. 221–224

- Cogan, p. 193–194

- Hartendorp, pg. Vol II, 401–402

- Cogan, p. 206

- Hartendorp, Vol II 509–512

- McCall, pp. 66, 146

- Pratt, 259–269

- Hartendorp, Vol. II, pg. 561–562

- "World War II: Liberating Los Baños Internment Camp". 12 June 2006. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- "44th Tank Battalion – 82nd Airborne Division – Special Troops 1952 Yearbook, Ft. Bragg, NC". American Ex-Prisoners of War. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Van Sickel, Emily The Iron Gates of Santo Tomas Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1992, pp. 314–315

- DioGuardi, Ralph. Roll out the Barrel … The Tanks are Coming. Bennington, VT: Merriam Press, 1988, pp. 9–10. DioGuardi called Stanley "Stevenson" but it is clear that he is referring to Ernest Stanley.

- Hartendorp, pg. 524–529

- "Tribute to Ernest Stanley". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "How Badly Was Manila Damaged During World War 2? - Filipino-American War". filipinoamericanwar.com. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Santo Tomas Documents, page 6 – Norwegian Merchant Fleet 1939–1945". www.warsailors.com.

- Video: Santo Tomas Prisoners Liberated, 1945/03/01 (1945). Universal Newsreel. 1945. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- Hartendorp, pp. 544–547

- Hartendorp, Vol, II, p. 547, 560

- Hartendorp, Vol. II, pp. 613–626

- Hartendorp, Vol II, p. 624.

- Ward, 181–183

- Ward, p. 198

- Pardoe, Katherine (December 8, 1961). "From Prisoner of War Doctor to Dean of Nursing: The Story of Beulah Ream Allen". The Galaxy. Provo, Utah: The Daily Universe. II (2): 6–7. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Stevens, Frederic Harper (1946). Santo Tomas Internment Camp: 1942-1945. Stratford House, Incorporated.

- "Transcript of interview". Library of Congress. December 19, 2001. p. 13. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- M., Norman, Elizabeth (1999). We band of angels : the untold story of American nurses trapped on Bataan by the Japanese. New York: Random House. p. 146. ISBN 978-0812984842. OCLC 39930499.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Herre, Albert W. C. T. (1945-05-11). "A. D. E. Elmer". Science. 101 (2628): 477–478. Bibcode:1945Sci...101..477H. doi:10.1126/science.101.2628.477. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17735519.

- Siemens, Greta (9 March 1945). "Shelley Mydans Tells Santo Tomas Prison Camp Life in New Book, 'The Open City'". The Stanford Daily. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Carter, Chelsea J. (April 7, 1999). "Bataan Nurses' Adventure Turned to Terror and WW II Prison Camp". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- "Virginia B. Hewlett, 67, Writer, Longtime Resident of Arlington". Washington Post. 1979-05-09.

Bibliography

- Springer, Paul (2015). "Surviving a Japanese Internment Camp: Life and Liberation at Santo Tomás, Manila, in World War II. Book review". H-Net. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Terry, Jennifer Robin (Spring 2012). "They 'Used to Tear Around the Campus Like Savages': Children's and Youth's Activities in the Santo Tomás Internment Camp, 1942–1945". Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth. 5: 87–117. doi:10.1353/hcy.2012.0003. S2CID 145748781. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Wilkinson, Rupert (11 January 2014). "My Father Was a Wartime Spy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

External links

- The Secret Story of Santo Tomas (Part 1)

- The Secret Story of Santo Tomas (Part 2)

- Ernest Stanley—January 21, 1948

- Lt. Col. Walter J. Landry Letter

- Victims of Circumstance documentary

- The Guardian obituary of Robin Prising mentions his memoir of his stay in the camp between the ages of 8 and 12: Manila, Goodbye

- Nancy Norton Obit

- Child internee Jean-Marie Faggiano (Heskett) tells her story of her stay at Santo Tomas between 1943 and 1945

- Yetta Lay Tuschka Life in Santa Tomas 1941-1944