Sarek National Park

Sarek National Park (Swedish: Sareks nationalpark) is a national park in Jokkmokk Municipality, Lapland in northern Sweden. Established in 1909, the park is among the oldest national parks in Europe. It is adjacent to two other national parks, namely Stora Sjöfallet and Padjelanta. The shape of Sarek National Park is roughly circular with an average diameter of about 50 km (31.07 mi).

| Sarek National Park | |

|---|---|

| Sareks nationalpark | |

The mountain Pierikpakte in the Äpar massif | |

| Location | Norrbotten County, Sweden |

| Coordinates | 67°17′N 17°42′E |

| Area | 1,970 km2 (760 sq mi)[1] |

| Established | 1909[2] |

| Governing body | Naturvårdsverket |

The most noted features of the national park are six of Sweden's thirteen peaks over 2,000 m (6,600 ft) located within the park's boundaries. Among these is the second highest mountain in Sweden, Sarektjåkkå, whilst the massif Áhkká is located just outside the park. The park has about 200 peaks over 1,800 m (5,900 ft), 82 of which have names. Sarek is also the name of a geographical area which the national park is part of. The Sarek mountain district includes a total of eight peaks over 2,000 m (6,600 ft). Due to the long trek, the mountains in the district are seldom climbed. There are approximately 100 glaciers in Sarek National Park.

Sarek is a popular area for hikers and mountaineers. Beginners in these disciplines are advised to accompany a guide since there are no marked trails or accommodations and only two bridges aside from those in the vicinity of its borders. The area is among those that receives the heaviest rainfall in Sweden, making hiking dependent on weather conditions. It is also intersected by turbulent streams that are hazardous to cross without proper training.

The delta of the Rapa River is considered one of Europe's most noted views and the summit of mount Skierfe offers an overlook of that ice-covered, glacial, trough valley.

The Pårte Scientific Station in Sarek (also known as the Pårte observatory) was built in the early 1900s by Swedish mineralogist and geographer Axel Hamberg. All the building material for the huts had to be carried to the site by porters.

Names of locations

In Sarek National Park, as in the most of Sápmi, a large number of the locations have names originating from the Sami languages.[3] These languages have several variations and their written forms have changed over time, which explains why some placenames do not always correspond with each other in different sources.[4]

The most common Sami names for locations or features in the park are tjåkkå or tjåkko (mountain), vagge (valley), jåkkå or jåkko (stream), lako (plateau) and ätno (river).[5] An example of this is Rapaätno, meaning Rapa River. These names are also the official Swedish names of the locations.

Geography

Location and borders

Sarek National Park is situated in the Jokkmokk Municipality, Norrbotten County, Sweden, north of the Arctic Circle, 50 km (31.07 mi) from the Norwegian border.

The area of the park is 1,977 km2 (763 sq mi) and it is adjacent to the national parks Padjelanta (in the west) and Stora Sjöfallet (in the north). The parks have a combined area of approximately 5,500 km2 (2,100 sq mi). There are also a number of nature reserves nearby.

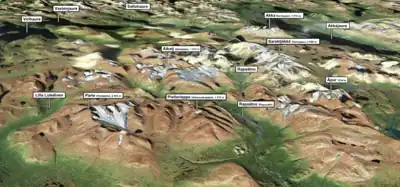

Topography

Sarek National Park is the most mountainous region in Sweden and it is the part of the country that mostly resembles an alpine countryside.[6] Within the park are 19 summits higher than 1,900 m (6,200 ft),[7] the most noted being the second highest summit in Sweden after the Kebnekaise – the Sarektjåkkå with a height of 2,089 m (6,854 ft).[8] The lowest altitude in the park is found in the southwest, near Lake Rittakjaure, at 477 m (1,565 ft).[7]

The park is made up of three types of landscape, sometimes difficult to differentiate between: large valleys, massive mountains, and high plateaux.[9] The largest valley of the park, which is also the most noted, is the Rapa Valley.[10] This valley occupies 40 km2 (15 sq mi)[11] of the park, including several branches, the most important of which are the Sarvesvagge, which climbs as far as Padjelanta,[12] the Kuopervagge — with an area of nearly 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi) — and the Ruotesvagge, surrounded by numerous glaciers, including those of Mount Sarektjåkkå.[13] Among the other notable valleys, outside the Rapadalen network, are the Kukkesvagge that makes up the north-eastern border of the park,[13] and the Njåtsosvagge near the southern border.[9] The largest plateau is the Ivarlako, east of the Pårte massif, with an altitude starting at 660–850 m (2,170–2,790 ft).[14] West of Pårte, the Luottolako plateau covers an area of 45 km2 (17 sq mi) and has an even higher altitude at 1,200–1,400 m (3,900–4,600 ft).[14]

Interspersed between the valleys and the plateaux, are massive mountains, often with several summits. The main ones are:

- Sarektjåkkå, highest point: Stortoppen, 2,089 m (6,854 ft)

- Pårte, Pårtetjåkkå, 2,005 m (6,578 ft)

- Piellorieppe, Kåtokkaskatjåkkå, 1,978 m (6,490 ft)

- Ålkatj, (Akkatjåkko, 1,974 m (6,476 ft)

- Äpar, 1,914 m (6,280 ft)

- Skårki, 1,842 m (6,043 ft)

- Ruotes, 1,804 m (5,919 ft)

Climate

| Climate data for Ritsem | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −11.5 (11.3) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

| Source: Swedish institute of metrology and hydrology (SMHI)[15] · [16] | |||||||||||||

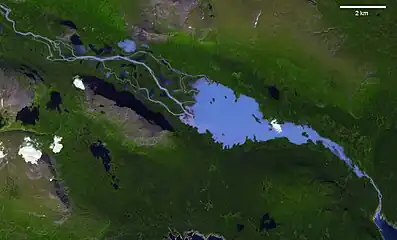

Hydrography

The park's main river is the Rapa River (Rapaätno). It originates from the glaciers of Sarektjåkkå and runs down the Rapa Valley as far as Lake Laitaure, and continues outside the park,[11] where it joins with the Lesser Lule River which becomes a tributary of the Lule River at its confluence.[11] This river is fed by thirty glaciers, contributing to a significant flow. The specific flow, the ratio between the average flow and the drainage basin, from these waters, is the most significant in Sweden.[17] The flow fluctuates strongly with the seasons, having an average of 100 m3⋅s−1 in July and about 4 m3⋅s−1 in winter, resulting in an average annual flow of approximately 30 m3⋅s−1.[18] The river also transports a significant quantity of sediment. In summer, it can carry up to 5,000–10,000 metric tons (11,000,000–22,000,000 lb) of sediment daily. In winter it only carries a few tons every day, resulting in an annual total of 180,000 metric tons (400,000,000 lb).[19] The sediment gives the river a grey-green colour and forms large deltas.[17] The main delta is formed at the confluence of the Rapaätno with its principal tributary, the river Sarvesjokk.[11]

Just before the confluence, the river braids for nearly 10 km (6.2 mi), forming a zone called Rapaselet.[20] The most noted of the deltas – and an emblem of the park – is the Laitaure delta (Laitauredeltat), which the river forms as it connects with Lake Laitaure.[11] The other significant rivers correspond to the principal valleys listed above. Most of them make up the drainage basin of Lesser Lule River. The rivers in the north part of the park flow into Lake Akkajaure, in the Stora Sjöfallet National Park, forming part of the hydrographic network of Lule älv.[17]

The park also contains several lakes.[21] The largest are the Alkajaure (altitude 751 m or 2,464 ft), on the border between the Sarek and the Padjelanta park, and the Pierikjaure (altitude 820 m or 2,690 ft) near the Stora Sjöfallet National Park.[22]

- The landscapes of Rapa River

Rapaselet

Rapaselet.jpg.webp) Skyview of Rapaselet

Skyview of Rapaselet The river delta of Laitaure

The river delta of Laitaure

Geology

Formation

The Sarek National Park lies within the Scandinavian Mountains, a mountain chain whose origin is still a matter of debate.[23] The rocks of the Scandinavian Mountains were put in place by the Caledonian orogeny,[24] forming a belt of deformed and displaced rocks now known as the Scandinavian Caledonides. Caledonian rocks overlie rocks of the much older Svecokarelian and Sveconorwegian provinces. The Caledonian rocks actually form large nappes (Swedish: skollor) that have been thrusted over the older rocks. Much of the Caledonian rocks have been eroded since they were put in place meaning that they were once thicker and more contiguous. It is also implyed from the erosion that the nappes of Caledonian rock reached once further east than they do today. The erosion has left remaining massifs of Caledonian rocks and windows of Precambrian rock.[24] The Caledonian orogeny resulted from the collision of the Laurentia and Baltica plates, 450 to 250 million years ago, with the disappearance of the Iapetus Ocean by subduction.[25] This happened just before the formation of the chain and was caused by the appearance of a rift, which finally led to the creation of the Atlantic Ocean.[25] The chain, once split open, continued to erode until it formed a peneplain.[26]

Starting about 60 million years ago, both the Scandinavian and the North-American sections suffered a tectonic uplift.[27] It is unclear what causes this and several hypotheses have been presented.[27] One of the theories is the influence of the Iceland hotspot which could have raised the crust.[27] Another hypothesis is the isostasy related to glaciations caused the uplift.[27] In any of those cases, the uplift allowed the ancient mountain chain to rise several thousand metres.[26]

The area of the national park, and the eastern Sarek Mountains in particular, was the last of part of Fennoscandia to be deglaciated. The last remnants of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet melted there slightly after 9,700 years BP.[28]

Erosion

The mountain chain was renewed and after that it was subjected to a new period of glacial erosion.[26] In the beginning of the Quaternary period, 15 million years ago, a significant glacial advance occurred.[29] The glaciers began to grow and move into the valleys where they gradually merged to form an ice sheet that covered the entire region.[29] Several further glaciations followed, forming the current landscape, with glacial valleys, cirques, nunataks etc.[30] The degree to which the chain was affected by the erosion depended mainly on the structure of the terrain, which explains the diversity in the topography of the area. The topography of Sarek, similar to that of Kebnekaise, is divided into sharply defined zones, particularly in respect to the two neighbouring national parks. This is mainly due to the existence of diabase and diorite dikes which are more resistant to erosion.[31] The park is intersected by a tangle of dikes created 608 million years ago, an era that probably corresponds with the first appearance of the rift during the formation of the Iapetus ocean.[32] These dikes represent intrusions into the Sarektjåkkå nappe, which is composed of sediments probably deposited in the rift basin.[33]

Glaciers

The park has over 100 glaciers, making it one of the most glacier-rich areas in Sweden. The glaciers are relatively small, the largest being Pårtejekna in Pårte at 11 km2 (4.2 sq mi). However, some of the others are relatively large for Sweden, since the largest Swedish glacier, Stuorrajekna in Sulitelma (south of Padjelanta), measures 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi).[30]

The evolution of the glaciers, particularly that of the Mikka (8 km2 (3.1 sq mi))[34] have been studied since the end of the 19th century, especially by mineralogist and geographer Axel Hamberg.[35] The other glaciers in the park have an evolution similar to that of the Mikka: in 1883 to 1895 they were mostly receding, then advanced a little in 1900 to 1916, after which they started to recede again.[36] Later they stabilised or grew, which was interpreted as being caused by the increase in winter precipitation related to global warming. The effect of the raised summer temperatures has been taken into account when assessing the data.[37] The receding of the glaciers has resumed at a particularly rapid pace during the first years of the 21st century.[38]

Wildlife

According to its WWF classification, Sarek National Park is situated in the Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands ecoregion, with a minor section in the Scandinavian and Russian taiga.[39] With regards to the flora and fauna, Sarek does not have a wide variety of species.[40] This is mainly explained by the fact that most of the park, except the south and south-east part,[7] is above the growth-limit of conifers,[40] which is at an altitude of about 500 m (1,600 ft) in this region.[41] Adding to this, unlike most of the region, Sarek National Park has few vast lakes or swamps.[40] A total of approximately 380 species of vascular plants have been found in the park,[42] as well as 182 species of vertebrates, 24 mammals, 142 birds, 2 reptiles, 2 amphibians and 12 fish.[40] Many of these species are on the Swedish red list of endangered species, notably the large carnivores.

The vegetation follows a fairly strict altitudinal zonation, as a result of the climate, and implying a similar zonation of fauna, although this is often less strict.[40]

Montane zone

The montane zones are relatively rare in the park, as its upper limit is about 500 m (1,600 ft) below most altitudes in these northern latitudes. The flora of this zone is constituted by old-growth forests of conifers, with mainly Scots pines and including Norway spruces. The pines can become very tall, particularly those around Lake Rittak, in the south part of the park. The undergrowth is mostly covered with mosses and lichens, in particular reindeer lichen, and also with Vaccinium myrtillus, Empetrum nigrum and cowberry.

The Sarek forests are a preferred habitat for numerous species of animals. Among the large carnivores, the brown bear is particularly frequent in the park and in the neighbouring Stora Sjöfallet. The bear fairly often also ventures into the subalpine region. The Eurasian lynx, classed as an endangered species in Sweden, is also found around the lakes of Rittak and Laitaure, and is also found in the subalpine forests of Rapa Valley. The red fox is relatively frequent, and is gradually extending its territory into the higher zones, where it competes with the arctic fox. Some small mammals that are frequent in the park are the European pine marten, the least weasel and the stoat. The ermine is also found in the higher regions. The herbivores include a very large number of moose as the forests and humid zones provide them with much food.[43] They often grow to an impressive size in the park, with enormous antlers.[44]

The birds in Sarek include a number of owls, such as the Ural owl, and woodpeckers, particularly the Eurasian three-toed woodpecker.[45] The grey-headed chickadee is also very common, as are the fieldfare, the song thrush and the redwing. Reptiles and amphibians, such as the viviparous lizard, the common frog and the common European viper, are mostly found in the forests.[46] The vipers of the Rittak region frequently reach remarkable sizes.[46]

Subalpine zone

The subalpine zone mostly consists of old-growth birch forests.[47] These forests are exceptional in terms of density and richness, making it possible for significant quantities of sediment material to be carried from the mountainside by the runoff and deposited in the watercourses.[48] This kind of transfer is particularly noted in the Rapa Valley.[48] In general, the transition between the conifer forests and the ones consisting of birch is more or less gradual, with the number of birches present in the coniferous forests increasing along with the altitude until the conifers have completely disappeared.[49] The size of the trees also diminishes with increasing altitude.[50] The upper altitude limit for the forests — which is also the tree line varies greatly throughout the park, from 600 m (2,000 ft) in the Tjoulta valley to over 800 m (2,600 ft) in the Rapa Valley.[21]

The birch forests also contain other species of trees. The number of rowan, grey alder, trembling poplar and hackberry is relatively high.[48] The alpine blue-sow-thistle is very widespread in this zone and is the food the bears prefer.[48] Garden angelica also grows in the forests, reaching a height of 2 to 3 m (6.6 to 9.8 ft).[48] Many other plants in this zone can also attain exceptional size.[51]

The division between the birch and coniferous forests is relatively blurred, with many of the animal species listed above also present in the subalpine zone.[52] Some small mammals are found more frequently here than in the coniferous forests, particularly several rodents such as the common shrew and the field vole. This is also the reindeers' habitat.[53] The Sami people living within the borders of the park, have domesticated the reindeer that stay in this zone during spring and move up to the alpine zone in summer.[53] Brown bears are common in the valleys of Tjoulta and Rapadalen.[54] However, it is the quantity and variety of birds is that enriches this zone.[55] The willow warbler, the common redpoll, the brambling, the yellow wagtail, the northern wheatear and the bluethroat are characteristic of the birch forests.[55] The willow ptarmigan is also more common in this area.[56] The raptors present in the zone are the merlin and the rough-legged buzzard, which often nests on the cliffs.[55] The gyrfalcon and the golden eagle usually prefer lower altitudes, but are nevertheless also found in the park.[57]

Alpine zone

The alpine zone is divided into several narrower zones.[58] The first subzone is mostly characterized by heathland, with many alder shrubs, mosses and lichens, and frequently dense mats of crowberries.[58] Different types of heaths can be distinguished. One type is mostly composed of a mix of alpine clubmoss and alpine bearberry.[59] Cushion pink and Lapland lousewort bring autumn colour to the heaths, which are otherwise fairly monochrome.[59] In the chalky soils of this subzone, the vegetation is very rich and forms prairies with mountain avens as the most characteristic species. purple saxifrage, velvetbells, alpine pussytoes and alpine veronica are also present.[59] With increasing altitude, the dwarf willow and lichens become more prominent, forming a second zone.[60] Gradually the plants become more scarce, and above 1,500 m (4,900 ft) there are only 18 types of plants present.[61]

There are three rare mammals who live in this zone. The wolverine inhabits a vast territory, roaming as far as the coniferous forests in winter, but the alpine zone is their main territory.[62] They mostly eat carrion, but they do also hunt living animals such as small rodents, birds and insects.[62] The wolverine is labelled as an endangered species in Sweden with an estimate of 360 individuals in the country in 2000.[63] The Arctic fox is a critically endangered species in Sweden, with only 50 individuals in the whole country.[64] They dig extensive networks of tunnels in areas above the tree-line, with several families inhabiting the same sett.[62] The park is one of the last sanctuaries for the gray wolf,[62] a species also critically endangered in Sweden.[65] In 1974–1975, the park was home to the only remaining wild wolf living in Sweden.[66] Although the wolf population is now growing,[67] they have not yet achieved a stable number in the park.[68]

In addition to these three mammals, Norway lemmings are also found in the park.[69] The number of lemmings varies extremely, with massive spikes in the population during some years, immediately followed by a very rapid decline. This phenomenon is not completely understood; it appears that favourable weather, and therefore a surplus of food, results in sudden population growths, but the reason for the decline is less obvious, although it is certain that contagious diseases play some role.[69] These cycles are also reflected in the populations of animals who prey on the lemmings.[69]

Many birds living at this altitude are associated with the humid zones. However, the alpine zone has its own characteristic species, such as the rock ptarmigan,[69] the snowy owl, the horned lark, the meadow pipit, the snow bunting[70] and the Lapland longspur.[71]

Humid zone

Although the park does not have the vast marshes and lakes characteristic of the rest of the region, water is nevertheless present everywhere. The humid zones are rich with a great diversity of flora and fauna. The stratification of vegetation is just as valid in the humid zones. In the montane region, the humid soils are covered with flowers such as the northern Labrador tea, cottonsedge, the Goldilocks buttercup, St Olaf's candlestick, common selfheal and common marsh-bedstraw.[72] In the subalpine zone, the humid prairies mainly have mats of Globe-flower, kingcup and twoflower violet.[48] In the alpine region there are many subalpine plants as well as the Pedicularis sceptrum-carolinum,[59] and the vegetation decreases as the altitude increases.

The humid zones of the park are well known for their rich diversity of birds. The common crane, the wood sandpiper and the short-eared owl are found at the lower altitudes,[45] while the Eurasian teal, the Eurasian wigeon, the greater scaup, the red-breasted merganser, the sedge warbler and the common reed bunting are common in the Laitaure delta and around Pårekjaure Lake.[56]

At higher altitudes, Vardojaure Lake is rich with birds, mostly ducks and also the European golden plover, characteristic of the alpine zone and sometimes found in the humid zones.[73] Låotakjaure Lake, on the border of Padjelanta, is interesting from an ornithological point of view.[74] Other rare species are also present, such as the lesser white-fronted goose, the great snipe, the red-throated pipit, the long-tailed duck and the bar-tailed godwit.[74] The Luottolako Plateau is also considered to be interesting, with the most significant concentration of purple sandpipers in Sweden.[75]

Arctic chars, trouts and common minnows are found in the park's lakes, rivers and streams.[52][57]

Tourism

Sarek National Park is mainly a high-alpine area with hardly any accommodation for tourists.[76]

Hiking trails

The Kungsleden hiking trail passes through the eastern part of the park, from Saltoluokta to Kvikkjokk. There are no cabins within the park, the Pårte, Aktse and Sitojaure cabins are just outside the park and they are accessible from both Saltoluokta and Kvikkjokk.

The Padjelanta Trail (Padjelantaleden), running from Kvikkjokk to Akkajaure, skirts the park along its western rim at Tarraluoppal, where the Tarraluoppal cabin is just on the border of the park.

Hazards

Due to the lack of shelters combined with rapidly shifting weather and rough terrain, it is recommended that hikers are well prepared and experienced before setting out on the trails of the park.[77]

Fording streams

There are few bridges in the park, and crossing streams (Sami: jokk) and rivers (Sami: ätno) can be dangerous for ill-equipped or inexperienced hikers. Warm weather increases the melting of the glaciers causing water levels to rise, therefore wading is often easier and safer early in the morning.[76]

The only ford across the Rapa River south of the Smaila Moot, is at Tielmaskaite. The ford is long and can only be used when waterlevels are low. Inexperienced hikers are recommended not to cross without a guide.

The glacier jokk from Pårtejekna, Kåtokjåhkå, has no fords. There is a bridge at the southernmost part of the stream (67°09′25.9″N 17°51′20.9″E). Hikers can also follow the streams up to the glacier and cross there, although this requires knowledge about glacier crossing.

Sarek in the winter

The lack of marked trails and accommodations makes it very difficult for visitors to hike in the park in winter, unless they are experienced and properly equipped. The steep slopes of the valleys also contributes to the risk for avalanches.[76]

Aktse

Aktse is an old farm settlement on the Kungsleden trail, approximately 1.3 km (0.81 mi) outside the boundaries of the park.

Alkavare

In 1788 a chapel was built at Alkavare (67°20′32.7″N 17°12′55.3″E) for the Sami that were herding reindeer in the area during summer. The walls of the building were dry set from local stone and the roof was made of timber, transported from Kvikkjokk, 60 km (37 mi) away. Originally, service was held every summer on June 25. It took the minister from Kvikkjokk three days to reach the chapel, and three days to get back. It was abandoned in the mid-19th century and renovated in 1961, and is still in use. As of 2015, it belongs to the Jokkmokk parish of the Church of Sweden, and church service is held throughout July.[78][79]

The Smaila Moot

Just above the canyon, formed by Smailajåkk as it descends toward Rapaätno, there is a cabin for the National Park Service (67°22′38″N 17°38′42″E). There is also a bridge over the Smailajåkk canyon which allows hikers to cross the stream safely. The bridge is removed every winter and put back in the spring, after the spring flood. The cabin is not open to hikers, but there is an emergency shelter as well as an emergency telephone and an outhouse there. The presence of the bridge and the fact that three of the major valleys in the park (Routesvagge, Rapa Valley and Koupervagge) converge there, has resulted in the name 'Smaila Moot' for the location which has become a meeting place for hikers in the park. It is also a preferred location to start a climb to the top of the Sarektjåkkå (2,089 m (6,854 ft)), via the Mikkajekna glacier.

Pastavagge

Pastavagge (in Lule Sami Orthography called Basstavágge) is a narrow valley, forming a pass, running from Pielavalta (Bielavallda) towards the east, ending north of Rinim on the shores of Lake Sitojaure (Sijddojávrre). The trekking distance from Pielvalta to Rinim is about 18 km (11 mi).[80] As there is a boat connection between Rinim and the Sitojaure cabins on the Kungsleden,[81] Pastavagge is a preferred route to and from central Sarek. The difference in altitude between the eastern entrance of the valley and the highest level of the pass is about 750 m (2,460 ft). Because of the steep climb, multiple fords and the high-alpine terrain, it usually takes at least a full day for hikers to traverse the pass.

History

The Sami people

The region's first inhabitants arrived with the retreat of the inland seas 8,000 years ago.[82] They were nomads who lived in Northern Scandinavia, and probably ancestors of the Samis.[82] Initially they were hunter-gatherers, living off reindeer.[83] For those people, the mountains often had religious connotations, and several were Sieidi (places of worship).[84] Offerings, such as antlers from reindeer, were often made in those places.[84] One of the most significant Sieidi was situated at the foot of Mount Skierfe (1,179 m (3,868 ft) high), at the entrance to the Rapa Valley.[84] Samis from the entire region gathered in this place for ceremonies.[84] Mount Apär itself, was believed to be the home of demons and legend tells of an illegitimate child's ghost inside it.[85]

Despite their hunter-gatherer way of life, the Samis kept some domesticated reindeer. They were milked and used for transport as well as other things.[68] Towards the end of the 17th century, the number of domesticated reindeer increased, and the Samis began to harmonize their travelling with the reindeer's search for pasture. Eventually, hunting the reindeer gave way to farming them.[68] The Samis in the mountains gradually developed a system of transhumance (movement between fixed summer and winter pastures).[68] They spent the winters on the park's plains and moved up into the mountains in summer, mainly to Padjelanta.[86] Sarek was mostly used as a corridor for travels, although certain prairies (Skarja and Peilavalta in particular) were used for pasture.[86] For shelter during their long journeys, which could last for several weeks, the inhabitants built huts (kåta) at selected places in the park.[87] Little by little, they left the reindeer to graze as they pleased, and stopped moving with the herds in the old way.[68]

Sarek and the Swedes

When the Swedish government took control over the Sami territory, the Sami had to pay the same taxes as other Swedes.[88] In the 17th century the Sami were evangelized by the Swedes, who often built churches and markets in locations where the Sami traditionally stayed during winter.[88]

The Swedes considered the mountains to be frightening and dangerous so they did not explore them.[89] When the first ore deposits were discovered in the region, the Swedes attempted to persuade the Sami to prospect for other ores in the mountains, in particular silver.[90] But in general, the Sami did not dare to reveal such information to the Swedes because they did not want to incur the disapproval of their fellow Sami.[90] An ore discovery was likely to result in the Sami being forced into near-slavery, working the mines and transporting the minerals.[90] The Alkavare deposit was an exception. Its existence was revealed to the Swedes by an extremely poor Sami, who became held in disdain by his tribe due to this.[90] The exploitation of the mine began in 1672, but it never rendered any profit and was abandoned in 1702.[90] A few attempts to reopen the mine has been made, but they have not been successful.[90] The ruins of two buildings and a little chapel are visible nearby the site.[90]

The first Swede to scientifically explore the mountains was Carl von Linné in his expedition to Lapland in 1732.[89] Later, in 1870, Gustaf Wilhelm Bucht mapped the region.[91] Shortly after, in 1881, the Frenchman Charles Rabot became the first man to reach the summit of Sarektjåkkå.[91] The 1890s marked the start of systematic scientific expeditions.[92] Most noted is the work of Axel Hamberg, who had participated in an expedition to Greenland led by Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Hamberg began his study of the region in 1895.[92] He studied the park, chiefly the glaciers, until his death in 1931.[92] He created a high quality map and constructed five cabins in the park, known as the Pårte station, where he conducted his studies of Sarek.[92] Axel Hamburg's work was particularly significant for widespread public recognition of the park.[92]

Protection

The 1872 creation of the world's first national park in Yellowstone[93] started a universal momentum for the protection of nature. In Sweden, the polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld became the first to propose using the new concept to protect areas of the Swedish landscape.[94] Axel Hamburg, Nordenskiöld and other scientists organized a plea for establishing Sweden's first national parks, Sarek in particular.[94] They convinced the Swedish botanist and member of the Riksdag Karl Starbäck from Uppsala University to raise the question in the Riksdag.[94] The proposition was accepted in May 1909, and the first nine national parks were established.[94] These were also the first in Europe. Among them were Sarek and its neighbour the Stora Sjöfallet.[95] The reason given for establishing the park was, as stated in official protocols, to "preserve a high mountain landscape in its natural state".[96]

In the middle of the 20th century, with developments in hydroelectricity in Sweden, dams were frequently built across the northern rivers of Sweden.[97] These barrages were also constructed in the national parks; the Stora Sjöfallet National Park lost nearly a third of its land area with the creation of a dam in 1919.[93] In 1961, an accord called the "Sarek peace" (Freden i Sarek) was forged, preventing hydroelectric developments in Sarek as well as in certain rivers, designated "national rivers".[98] This also led to the establishing of Padjelanta National Park.[98]

In 1982, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) mentioned a vast zone including Sarek National Park in its tentative list of natural sites to be classified as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.[99] Sweden proposed that part of this zone, the Sjaunja nature reserve, should be included in the list, and in 1990 the IUCN recommended an extension to the proposed area.[99] In 1996, Sarek Park was classed as a World Heritage Site including the adjoining areas of Padjelanta, Stora Sjöfallet, Sjaunja and Stubba nature reserves, Muddus National Park and three adjacent areas, making a total of 9,400 km2 (3,600 sq mi). The whole area was added to the World Heritage as a mixed site ("of cultural and natural value") called the Laponian area.[83] The park also became part of the Natura 2000 network.[100] Being on the World Heritage list allowed the park to have its first protection plan. The plan was written with thorough consultation of the Sami, who had not been consulted when the park was established.[101] The WWF paid for this process.[101]

The 2007 Environmental Protection Agency plan for the national parks includes a plan to expand Sarek to incorporate the area of the Laitaure Delta and the Tjuoltadalen Valley to the south part of the park.[102] This extension had already been proposed in the 1989 plan, but the situation changed with the World Heritage designation as the proposed extension would make up a sizable part of the Laponian Region.[102]

History of tourism

Sarek National Park is viewed by many Swedes as one of the most beautiful landscapes of their country. The enthusiasm for it was started by Axel Hamberg's book on the park, presenting Sarek as the joy of the Swedish Lapland.[103]

The Swedish Tourist Association (STF) was created in 1885. In 1886, they mentioned Sarek as a potential tourist site for the first time.[104] However, the number of tourists was not more than a few dozen.[104] In 1900, the association studied the possibility of creating a long hiking trail crossing the Lapland mountains, between Abisko and Kvikkjokk.[105] The initial proposal was for a marked trail that passed through the park, a boat crossing of the Rapaselet and a mountain hut beside the river.[103][105] The project was abandoned and the STF concentrated mostly on Kebnekaise and Sylan.[103] The trail (Kungsleden) was built, but only coming close to the park in the southeast corner of it.[106]

In 1946, Dag Hammarskjöld popularised the expression "vår sista stora vildmark" ("our last great wilderness").[97] Dag Hammarskjöld advocated a growing tourism in the park, that took care not to damage the environment.[97] Edvin Nilsson's 1970 book on the park strengthened its reputation, increasing the number of tourists from two or three hundred in the 1960s, to 2,000 in 1971.[107] This sudden success caused several problems such as the temporary overcrowding on certain trails in the Rapa Valley, which were not designed to accommodate so many visitors.[107]

Management and regulation

The general case

As for the majority of the Swedish national parks, the management and administration of the park is divided between the Environmental Protection Agency of Sweden and the County administrative board.[108] The Environmental Protection Agency is in charge of proposing new national parks in consultation with the county and municipality council. The establishing of each new park requires a decision from the Riksdag.[108] After that, the land is bought by the government through the intermediary of the Environmental Protection Agency.[108] The rest of the park's management is done by the county council. In Sarek's case, this is the Norrbotten County council.

The park rules are relatively strict, to preserve the park in its near-pristine condition. Fishing, hunting, picking flowers and any other activity that could damage the wildlife are all forbidden, except for picking berries and edible mushrooms.[109] Similarly, no motorised vehicles are allowed in the park.[109]

The Sami exception

There are several exceptions in the laws about management and regulation of the national parks regarding the Sami. In 1977, the Sami people were recognised by Sweden as an indigenous people and a minority group, which implies that the people and their way of life are protected by law.[110] This grants the Sami the right to farm reindeer in the park.[109] The park is situated on territory belonging to the Sami communities of Sirkas, Jåhkågaskka and Tuorpons, the Sami who are members of these communities are also allowed to pasture their reindeer in the park.[111] In carrying out these activities, the Sami have the right to use motorised vehicles such as snowmobiles or helicopters.[109]

These rights are sometimes conflicting with the protection of wildlife. An example of this is when carnivores attack the Sami reindeer. Such an incident occurred in 2007, when an unregistered wolf, a protected and endangered species in Sweden, wandered into an area in Tjåmotis (30 km (19 mi) southeast of the Rapa Valley) where reindeer were grazing. The wolf was captured, radio-collared and DNA tested. It was kept under surveillance and attempts were made to scare it away, but after it had killed several reindeer and disrupted the herd, a decision was made to shoot it. The decision and the killing were made collectively by the Norrbotten County Administrative Board, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Sami in accordance with the national nuisance wildlife management act.[112][113]

There is also an ongoing debate about the damages caused by snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles in the parks.[114] The snowmobiles have become increasingly popular and numerous, while global warming has made the terrain more vulnerable to the vehicles. Joyrides by visitors outside the marked trails have become a problem, especially for the Sami, since they claim that the disruptions made by snowmobiles may cause the pregnant female reindeer to drop their calves prematurely.[115][116][117]

In popular culture

The park was the main setting of the 2017 film The Ritual, directed by David Bruckner.

See also

References

- "Sarek National Park" (PDF). Naturvårdsverket. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Sarek National Park". Swedish Environmental Agency. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 8

- "Samiska ortnamn" (in Swedish). Institut for språk och folkminnen. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, pp. 131–133

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 10

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 11

- "Sarek National Park". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 97

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 102

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 99

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 106

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 110

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 112

- "Normalvärden för temperatur för 1961–1990". SMHI. Retrieved 26 October 2011. : station 17793 (Ritsem A)

- "Normalvärden för nederbörd för 1961–1990". SMHI. Retrieved 26 October 2011. : station 17793 (Ritsem A)

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 30

- Axelsson, Valter (1967), "The Laitaure Delta: A Study of Deltaic Morphology and Processes", Geografiska Annaler, Series A, Physical Geography, 49 (1): 1–127, doi:10.2307/520865, JSTOR 520865

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 31

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 100

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 21

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 29

- Medvedev, Sergei; Hartz, Ebbe H. (2015). "Evolution of topography of post-Devonian Scandinavia: Effects and rates of erosion". Geomorphology. 231: 229–245. Bibcode:2015Geomo.231..229M. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.12.010.

- Lundqvist, Jan; Lundqvist, Thomas; Lindström, Maurits; Calner, Mikael; Sivhed, Ulf (2011). "Fjällen". Sveriges Geologi: Från urtid till nutid (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Spain: Studentlitteratur. pp. 323–340. ISBN 978-91-44-05847-4.

- Søren B. Nielsen; Kerry Gallagher; Callum Leighton; Niels Balling; Lasse Svenningsen; Bo Holm Jacobsen; Erik Thomsen; Ole B. Nielsen; Claus Heilmann-Clausen; David L. Egholm; Michael A. Summerfield; Ole Rønø Clausen; Jan A. Piotrowski; Marianne R. Thorsen; Mads Huuse; Niels Abrahamsen; Chris King; Holger Lykke-Andersen (2009), "The evolution of western Scandinavian topography: A review of Neogene uplift versus the ICE (isostasy–climate–erosion) hypothesis" (PDF), Journal of Geodynamics, 47 (2–3): 72–95, Bibcode:2009JGeo...47...72N, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2008.09.001, S2CID 130108915

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 12

- Japsen, Peter; Chalmers, James A. (2000), "Neogene uplift and tectonics around the North Atlantic: overview", Global and Planetary Change, 24 (3–4): 165–173, Bibcode:2000GPC....24..165J, doi:10.1016/s0921-8181(00)00006-0

- Stroeven, Arjen P.; Hättestrand, Clas; Kleman, Johan; Heyman, Jakob; Fabel, Derek; Fredin, Ola; Goodfellow, Bradley W.; Harbor, Jonathan M.; Jansen, John D.; Olsen, Lars; Caffee, Marc W.; Fink, David; Lundqvist, Jan; Rosqvist, Gunhild C.; Strömberg, Bo; Jansson, Krister N. (2016). "Deglaciation of Fennoscandia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 147: 91–121. Bibcode:2016QSRv..147...91S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.09.016.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 13

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 57

- Andréasson, Per-Gunnar; Gee, David G. (1989), "Bedrock Geology and Morphology of the Tarfala Area, Kebnekaise Mts., Swedish Caledonides", Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 71 (3/4): 235–239, doi:10.2307/521393, JSTOR 521393

- Svenningsen, O.M. (2001), "Onset of seafloor spreading in the Iapetus Ocean at 608 Ma: precise age of the Sarek Dyke Swarm, northern Swedish Caledonides", Precambrian Research, 110 (1–4): 241–254, Bibcode:2001PreR..110..241S, doi:10.1016/s0301-9268(01)00189-9

- Svenningsen, O.M. (1995), "Extensional deformation along the Late Precambrian-Cambrian Baltoscandian passive margin : the Sarektjåkkå nappe, Swedish Caledonides", Geol Rundsch, 84 (3): 649–664, doi:10.1007/s005310050031

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 56

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 29

- Karlén, Wibjörn; Denton, George H. (1975), "Holocene glacial variations in Sarek National Park, northern Sweden", Boreas, 5: 25–56, doi:10.1111/j.1502-3885.1976.tb00329.x

- Holmlund, Per; Karlén, Wibjörn; Grudd, Håkan (1996), "Fifty Years of Mass Balance and Glacier Front Observations at the Tarfala Research Station", Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 78 (2/3): 105, Bibcode:1996GeAnA..78..105H, doi:10.2307/520972, JSTOR 520972

- Baltscheffsky, Susanna (30 August 2008). "Sareks glaciärer försvinner fort". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish).

- "Protected Area : Sarek". Global Species. Retrieved 2012-01-21.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 53

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 20

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 33

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 64

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 65

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 67

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 68

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 36

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 37

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 34

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 41

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 38

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 69

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 70

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 71

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 72

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 73

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 77

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 42

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 43

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 46

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 47

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 87

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (2000). "Åtgärdsprogram för bevarande av Järv" (PDF) (in Swedish).

- Naturvårdsverket (2008). "Åtgärdsprogram för fjällräv 2008–2012" (PDF) (in Swedish).

- Naturvårdsverket (2003). "Åtgärdsprogram för bevarande av Varg" (PDF) (in Swedish).

- "Utsettning av ulv i Norge og Sverige" (PDF). Rovdur (in Norwegian). Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Ericsson, Göran; Heberlein, Thomas A. (2003). "Attitudes of hunters, locals, and the general public in Sweden now that the wolves are back". 111. Biological Conservation: 149–159.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Strategiska frågor för utveckling av Världsarvet Laponia" (PDF). Laponia (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, pp. 88–91

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 95

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 85

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 35

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 78

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, pp. 79–81

- Curry-Lindahl 1968, p. 93

- "Sarek". Environmental Protection Agency (Sweden). Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Kläder och utrustning" [Clothes and equipment]. www.sverigesnationalparker.se. Environmental Protection Agency (Sweden). Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Alkavare kapell". www.svenskakyrkan.se. Church of Sweden. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Hamberg, Axel (1926). "Alkavare lappkapell: en kulturbild" (PDF). Svenska Turistföreningens årsskrift. Svenska Turistföreningen. 1926: 263–272. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- "Topografisk karta". www.lantmateriet.se. Lantmäteriet. 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- "Båttrafik längs lederna". www.svenskaturistforeningen.se. Svenska Turistföreningen. 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- Kihlberg 1997, p. 30

- "Région de Laponie". Patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO (in French and English). Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Kihlberg 1997, pp. 31–32

- Kihlberg 1997, p. 34

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 14

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 23

- "Historia i Laponia" (PDF). Laponia (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2004. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 26

- "The Alkavare Silver Mine…". Laplandica. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 27

- Abrahamsson 1993, pp. 28–29

- Grundsten, Claes (2010). Max Ström (ed.). National parks of Sweden. Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-7126-160-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Allting om Jokkmokk" (PDF). Jokkmokks kommun (in Swedish). Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- "Les parcs nationaux dans le monde". Parcs nationaux (in French). Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- "Förordning om ändring i nationalparksförordningen (1987:938)" (PDF). Lagbocken (in Swedish). Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 39

- "Energifrågan". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "World heritage nomination — IUCN summary, the lapponian area (Sweden)" (PDF). Patrimoine mondial. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- "Bevarandeplan Natura 2000 Sarek SE0820185" (PDF). Länsstyrelsen i Norrbotten (in Swedish). Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- "Samverkan om Laponia får WWF-pris". Naturvårdsverket (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Environmental Protection Agency (Sweden) (2007). Nationalparksplan för Sverige – Utkast och remissversion (PDF) (in Swedish).

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 37

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 35

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 36

- "Vandringleder". www.kvikkjokkfjallstation.se. Kvikkjokks fjällstation. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Abrahamsson 1993, p. 40

- "Nationalparksförordning (1987:938)". Notisum (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Förslag till nya föreskrifter för nationalparkerna/suoddjimpárkajda Sarek Stora Sjöfallet/Stuor Muorkke Muddus/Muttos Padjelanta/ Badjelánnda och luonndoreserváhtajda/naturreservaten Sjávnja/Sjaunja Stubbá/Stubba" (PDF). Naturvårdsverket (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- "Diskriminering av samer – samers rättigheter ur ett diskrimineringsperspektiv". Sametinget (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- "Sarek". Länsstyrelsen i Norrbotten (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Varg skjuten i Jokkmokk" [Wolf shot in Jokkmokk]. www.nsd.se. Norrländska Socialdemokraten. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Vargjakt i Norrbotten" [Wolf hunt in Norrbotten]. www.jaktojagare.se. Jägarnas Riksförbund. 7 February 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Edin, Ronny (2007). "Terrängkörning i svenska fjällvärlden" [Terrain vehicles in the Swedish mountain area] (PDF). www.lansstyrelsen.se. Norrbotten County Administrative Board. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Skoterförbud i fjället" [Ban on snowmobiles in the mountains]. www.vk.se. Västerbottens-Kuriren. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Lindgren, Maria; Callne, Lena (16 April 2014). "Dålig respekt för skoterförbud i fjällen" [Prohibition for snowmobiles not respected]. www.sverigesradio.se. Sveriges Radio. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- "Swedish Snowmobile Regulations". www.snoskoterradet.se. National Council on Snowmobiles. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

Bibliography

- Abrahamsson, Tore (1993), Bonnier Alba (ed.), Detta är Sarek: [vandringar, bestigningar, geologi, fauna, flora] (in Swedish), Stockholm, ISBN 91-34-51134-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Curry-Lindahl, Kai (1968), Rabén & Sjögren (ed.), Sarek, Stora Sjöfallet, Padjelanta: three national parks in Swedish Lapland, Stockholm

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kihlberg, Kurt (1997), Nordkalotten (ed.), Laponia : Europas sista vildmark : Lapplands världsarv = Laponia : the last wilderness in Europe : Lapland's World Heritage Site (in English and Swedish), Rosvik, ISBN 91-972178-8-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)