Tsuutʼina language

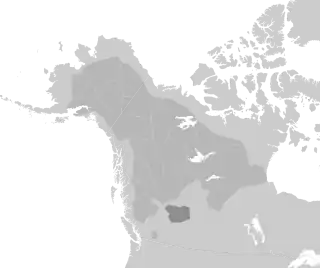

The Tsuutʼina language[2] (formerly known as Sarcee or Sarsi)[3]: 2 [4] is spoken by the people of the Tsuutʼina Nation, whose reserve and community is near Calgary, Alberta. It belongs to the Athabaskan language family, which also include the Navajo and Chiricahua of the south, and the Dene Suline and Tłı̨chǫ of the north.

| Tsuutʼina | |

|---|---|

| Sarcee | |

| Tsúùtʼínà | |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Alberta |

| Ethnicity | Tsuutʼina |

Native speakers | 80 (2016 census)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | srs |

| Glottolog | sars1236 |

| ELP | Tsuut'ina |

| |

Sarcee is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Nomenclature

The name Tsuutʼina comes from the Tsuutʼina self designation Tsúùtʼínà, meaning "many people", "nation tribe", or "people among the beavers".[5] Sarcee is a deprecated exonym from Siksiká.

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants of Tsuutʼina are listed below, with symbols from the standard orthography in brackets:

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | lateral | plain | rounded | |||||

| Stop | plain | p ⟨b⟩[lower-alpha 1] | t ⟨d⟩ | ts ⟨dz⟩ | tɬ ⟨dl⟩ | tʃ ⟨dj⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | kʷ ⟨gw⟩[lower-alpha 2] | ʔ ⟨ʼ⟩ |

| aspirated | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | tsʰ ⟨ts⟩ | tɬʰ ⟨tl⟩ | tʃʰ ⟨tc⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | kʷʰ ⟨kw⟩[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| ejective | tʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | tsʼ ⟨tsʼ⟩ | tɬʼ ⟨tlʼ⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨tcʼ⟩ | kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩ | kʷʼ ⟨kwʼ⟩ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | s ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨ł⟩ | ʃ ⟨c⟩ | x ⟨x⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | |||

| voiced | z ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨j⟩ | ɣ ⟨γ⟩ | ||||||

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | |||||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | ||||||

- /p/ is only found in mimetic buꞏ 'to buzz' and borrowed buꞏs 'cat'.

- The phonemic status of [kʷ] and [kʷʰ] is questionable; they might be /ku, kʰu/ before another vowel. /kʷʼ/ is quite rare but clearly phonemic.

Vowels

There are four phonemically distinct vowel qualities in Tsuutʼina: /i a ɒ u/, represented〈i a o u〉. While /a/ and /ɒ/ are fairly constant, /i u/ can vary considerably.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i ~ e ⟨i⟩ | u ~ o ⟨u⟩ |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | ɒ ⟨o⟩ |

Vowels are also distinguished by length and tone, similar to other Athabaskan languages, so that Tsuutʼina, taking the total number of vowel phonemes to 24 (i.e. / ī í ì īː íː ìː ā á à āː áː àː ɒ̄ ɒ́ ɒ̀ ū ú ù ūː úː ùː ɒ̄ː ɒ́ː ɒ̀ː /).

- long vowels are marked with an asterisk, e.g., a* [aː]

- high tone is marked with an acute accent, e.g., á

- low tone is marked with a grave accent, e.g., à

- mid tone is marked with a macron, e.g., ā

Nouns

Nouns in Tsuutʼina are not declined, and most plural nouns are not distinguished from singular nouns. However, kinship terms are distinguished between singular and plural form by adding the suffix -ká (or -kúwá) to the end of the noun or by using the word yìná.

People

- Husband - kòlà

- Man, human - dìná

- Wife - tsʼòyá

- Woman - tsʼìkā

- grandmother - is’su

- grandfather - is’sa

- mother - in’na

- father - it’ta

Nature

- Buffalo, cow - xāní

- Cloud - nàkʼús

- Dog - tłí(chʼà)

- Fire - kù

- Mud, dirt - gútłʼìs

- Snow - zòs

- Water - tú

Words and phrases

- my name is (..) - sizi

Noun possession

Nouns can exist in free form or possessed form. When in possessed form, the prefixes listed below can be attached to nouns to show possession. For example, más, "knife", can be affixed with the 1st person prefix to become sìmázàʼ or "my knife". Note that -mázàʼ is the possessed form of the noun.

Some nouns, like más, as shown above, can alternate between free form and possessed form. A few nouns, like zòs, "snow", are never possessed and exist only in free form. Other nouns, such as -tsìʼ, "head", have no free form and must always be possessed.

Typical possession prefixes

- 1st person - si-

- 2nd person - ni-

- 3rd person - mi-

- 4th person (Athabascan) - ɣi-

Language revitalization

Tsuutʼina is a critically endangered language, with only 150 speakers, 80 of whom speak it as their mother tongue, according to the 2016 Canadian census.[1] The Tsuutʼina Nation has created the Tsuutʼina Gunaha Institute with the intention of creating new fluent speakers. This includes full K-4 immersion education at schools on the Nation[6] and placing stop signs in the Tsuutʼina language at intersections in the Tsuutʼina Nation.[7]

Bibliography

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1971a). "Vowels and Tone in Sarcee", Language 47, 164-179.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1971b). "Morphophonemics of Two Sarcee Classifiers", International Journal of American Linguistics 37, 152-155.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1971d). "Sarcee Numerals", Anthropological Linguistics 13, 435-441.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1972). "Sarcee Verb Paradigms", Mercury Series Paper No. 2. Ottawa: National Museum of Man.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1973b). "Complementation in Sarcee". [Unpublished?]

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1978b). "The Synchronic and Diachronic Status of Sarcee ɣy", International Journal of American Linguistics 43, 259-268.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1978c). "Palatalizations and Related Rules in Sarcee", in: Linguistic Studies of Native Canada, eds. Cook, E.-D. and Kaye, J. 19-36. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1978d). "The Verb 'BE' in Sarcee", Amerindia 3, 105-113.

- Cook, Eung-Do. (1984). A Sarcee Grammar. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0200-6.

- Goddard, P. E. (1915). "Sarcee Texts", University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 11, 189-277.

- Honigmann, J. (1956). "Notes on Sarsi Kin Behavior", Anthropologica 11, 17-38.

- Hofer, E. (1973). "Phonological Change in Sarcee". [Unpublished?]

- Hofer, E. (1974). "Topics in Sarcee Syntax". M.A. Thesis. The University of Calgary.

- Hoijer, H. and Joël, J.. (1963). "Sarcee Nouns", in Studies in the Athabaskan Languages, eds. Hoijer, H. et al., 62-75.

- Li, F.-K.. (1930). "A Study of Sarcee Verb Stems", International Journal of American Linguistics 6, 3-27.

- Sapir, E. (1924). "Personal Names Among the Sarcee Indians", American Anthropologist n.s. 26, 108-199.

- Sapir, E. (1925). "Pitch Accent in Sarcee, An Athabaskan language", Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris n.s. 17, 185-205.

- Sarcee Culture Program. 1979. Tsu Tʼina and the Buffalo. Calgary.

See also

References

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Knowledge of languages". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Tsuutʼina Gunaha Institute". Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- McDonough, Joyce; O'Loughlin, Jared & Cox, Christopher (2013-06-02). An investigation of the three tone system in Tsuutʼina (Dene). International Congress on Acoustics. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. Montreal: Acoustical Society of America. p. 060219. doi:10.1121/1.4800661. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

This study is part of the documentation and conservation of Tsuut'ina (formerly Sarcee, Sarsi; ISO 639-3: srs), a northern Dene (Athabascan) language, by a collaboration of academic and Tsuut'ina community members.

- Cox, Christopher (2013). Structuring stories: personal and traditional narrative styles in Tsuut'ina (PDF). Athabaskan Languages Conference 2011. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

This study investigates associations between particular lexical-grammatical features of Tsuut'ina (formerly Sarcee, Sarsi; ISO 639-3: srs) and the narrative contexts in which they are attested.

- Cook (1984: 7 ff)

- "New high school for Tsuutʼina Nation will have strong focus on culture and curriculum | CBC News".

- Tsuut’ina Nation displaying Indigenous language stop signs