Sasanian glass

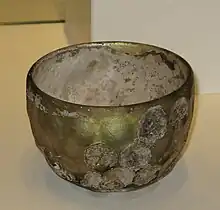

Sasanian Glass is the glassware produced between the 3rd and the 7th centuries AD within the limits of the Sasanian Empire of Persia, namely present-day Northern Iraq (ancient Mesopotamia), Iran (Persian Empire) and Central Asia. This is a silica-soda-lime glass production characterized by thick glass-blown vessels relatively sober in decoration, avoiding plain colours in favour of transparency and with vessels worked in one piece without over- elaborate amendments. Thus the decoration usually consists of solid and visual motifs from the mould (reliefs), with ribbed and deeply cut facets, although other techniques like trailing and applied motifs were practised (See Figure 1).

Some considerations about the definition of Sasanian Glass

Despite there being a general agreement concerning what Sasanian Glass is, there are no clear criteria to describe it. Therefore, before continuing with a further explanation is necessary to clarify it. Usually, it is defined by means of period, territory and style.

Sasanian glass is frequently referred to with the ambiguous term Pre-Islamic Persian Glass. But some scholars (e.g. Goldstein 2005) consider the Achaemenid (550-330BC), Parthian (247BC-226AD) and Sasanian (224-642AD) productions as Pre-Islamic whereas others (e.g. Meyer 1995) consider only the 7th–8th centuries AD immediately before the Islamic Golden Age and the first Abbasid caliphate. Sasanian Glass is also named Persian Glass, incorporating all the assemblage manufactured in Persia from the 3rd to the 19th centuries AD (Newman 1977).

The Sasanian Empire spanned a vast area from the Fertile Crescent to the Central Asian steppe, but with periods of expansion and contraction, reaching Damascus, Jerusalem, Egypt, Yemen or Pakistan. Some of the works were produced in the peripheral regions bordering the Empire and others came from beyond but followed Sasanian designs. This creates "uncertainties about the precise place of manufacture of many Sasanian creations" (Demange 2007, 9) and confusion among terms since Mesopotamia, for instance, can be at the same time Seleucia (Achaemenid), Ctesiphon (Sasanian) or Baghdad (Islamic).

Finally, the stylistic criteria can be very tricky due to several reasons. First, there is a considerable difficulty in discerning between the Parthian and Sasanian tradition (Negro Ponzi 1968-69), Byzantine and Sasanian (Goldstein 2005) and Sasanian and Islamic (Whitehouse 2005) to the extent that ‘Sasanian’ glassware, if carefully analysed, becomes Parthian (Negro Ponzi 1972, 216); that Byzantine pieces have many possibilities of being Sasanian (Saldern 1967), or that the same author examining the same specimen can conclude the piece is Sasanian in a first paper and Islamic in a second report (Erdmann 1950 and 1953).[1] Second, the most characteristic method of decoration utilized by Sasanian artisans, the wheel-cut technique (See Figure 2) was not originated at all by them. There are splendid examples of wheel-cut vessels at least from the 5th century BC among the Achaemenians that are known both in East and West (Goldstein 1980). "Everything wheel-cut is not Sasanian." (Rogers 2005, 24).

Origins of Sasanian Glass

See Roman glass or Anglo-Saxon Glass entries for the differences between glassmaking and glassworking

The Sasanian craftsmen smoothly continued the tradition of glassworking, inherited from the Romans and Parthians, transmitting it to the Islamic artisans when their Empire collapsed (Goldstein 1982 and 2005). Although they began from plain and mould-blown vessels close to the Parthian taste (Negro Ponzi 1984, See Figure 3), they soon generated their own genuine style especially recognizable in the ’typical hemispherical bowls with round or hexagonal deep incised facets’ (Negro Ponzi 1987, 272) and widely expanded it throughout all the Sasanian territory and even beyond their borders.

However, there is no such continuity in glassmaking. Recent studies have demonstrated that there are clear differences between the composition of Roman, Sasanian and Syro-Palestinian - contemporary to the latest- productions (Freestone 2006) and also between Sasanian, Parthian and Islamic manufactures (Mirti et al. 2008 and 2009; Brill 2005). There is evidence that Roman glass was recycled to make Parthian glazes (Wood and Hsu 2020; Wood 2022).

The recipe of Sasanian glassmakers

Sasanian glass is a silica-soda-lime composition with high levels of K and Mg: this means the use of plant ash as a source of soda. The Roman and the Parthian glass, on the other hand, employed mineral salts for this purpose (Freestone 2006, Mirti et al. 2009). Consequently, there is no continuation of the formula.

Moreover, Sasanian glasses also show differences when compared with other plant-ash soda glasses. Freestone analysis revealed that Syro-Palestinian productions were lower in Mg than Sasanian ones, and Brill (2005, 75) concluded that there is a general ‘overlapping but no close agreement’ between the Sasanian and the later Islamic glass and that the former ‘do not bear a close enough chemical resemblance to any of the particular groups of Islamic glasses’.

In fact, the Sasanian glass is different even within itself. Three recipes have been identified for glassmaking (Mirti et al. 2008). The first one (minoritarian) is a silica-soda-lime glass with one evaporite as a flux that mainly appears in the earliest stages of the Empire (3rd century). The second group is divided into two other subgroups, both using sodic ash but exploiting different plants. One of them is present from the beginning of the Dynasty and the other from the 4th century onwards. A crucial difference between them, apart from the one mentioned, is that the second subgroup always utilised a purer source of silica. Since this third recipe produced more transparent glass, found in more sophisticated objects than the ones worked with the other recipes (Mirti et al. 2009) this has been interpreted as an argument for the existence of diverse formulas to satisfy the demand of different qualities of glass. It is significant that, in the quest for transparency meeting the taste of the Sasanians, purer silica was also occasionally utilised in the first subgroup. Recently, compositional analysis indicates that purer silica sources exhibiting lower variation were used in later periods, potentially suggesting standardisation of practice associated with a centralised glass-making industry (Wood and Greenacre 2021).

Techniques of Sasanian glassworkers

The only technological innovation attributed to Sasanian glassworkers is "the casting of a glass blank that could be carved as if it were a hardstone" (Rogers 2005, 23). The rest of the arts were acquired from previous artisans. Thus wheel-cutting from Achaemenians (at least the 5th century BC if not earlier, Saldern 1963; Goldstein 1980); applied ornaments like trails and blobs of glass were introduced around the 3rd–2nd centuries BC and glassblowing appeared in the 1st century BC. Sasanian glass craftsmen did not invent anything revolutionary but rather developed the available arts to a degree of mastery. In fact, their expertise in glassworking settled the ‘foundation for virtually all the methods used to produce glass in the Islamic world’ (Goldstein 2005, 11).

Although it is possible to find some core-form objects produced by the Sasanians, these are rarities (Goldstein 2005, 28-62). The whole of the Sasanian assemblage is glassblowing. The most frequent technique among the Sasanians was to blow the object giving it a basic shape and then finishing it with the help of paddles, pincers and shears. Other techniques frequently used were mould-blowing and mould-pressing. These two use the mould as the essential part of the process (See Figure 4). In the former, the object is blown inside a mould, acquiring the shape and decoration of the final object. In the second stage the mould is removed and the object is blown to the appropriate size. Mould-pressing consists of pressing the glass against an open mould, obtaining a positive of the final object.

These methods produced slightly asymmetrical objects but have the advantage of permitting a huge versatility in shapes and obtaining articles practically finished since shapes (and patterns) are given with any of the techniques and by means of non-complicated solutions, pinching, cutting, polishing, and applying, the final object is obtained (Negro Ponzi 1968; Goldstein 2005; Whitehouse 2005). These techniques agreed with the Sasanian taste for plainly decorated vessels; thus they do not use the cameo or the scratching solutions that were extremely popular during Islamic times. Instead they prefer to work the glass cold, polishing and panel-and-face-cutting, creating ‘a contrast of highlights and shadows, while at the same time providing a better grip’ (Goldstein 2005, 30).

The creations of Sasanian glassworkers

‘Best known Sasanian glasses are those decorated with overall patterns of ground, cut and polished hollow facets’ (Whitehouse 2005, 41, See Figure 5), but this appears around the 5th century AD. Before it, the ‘commonest type, spread in all the proto and middle Sasanian levels’ is a bowl or tumbler with ‘straight or slightly rounded walls’ (Negro Ponzi, 1984, 34).

The repertory of forms and functions is, nonetheless, markedly wider: lamps, jars, flasks, tumblers, decanting siphons, dishes, bottles, scrolls or pen cases, jugs, beakers, cups, goblets, sprinklers, balsamaria, chalices, spoons, etc., in all kind of sizes and shapes; round, square, cylindrical, tubular, tronco-conic, etc. and with multiple combinations of them: round bottles with long/short/cylindrical/square necks, tripod-footed bowls, hexagonal, elongated or spherical flasks, square bottles with tronco-conical necks, etc. both plain and decorated and both for ordinary and luxury uses. It is worth mentioning that there is solid evidence (Meyer 1995, Mirti et al. 2008) pointing out that Sasanian glass production was not only for goods of luxury items for a selected elite but also concerned with the manufacture of quotidian goods.

A constant within all the Sasanian production is the search for transparency in the glasses. As has been mentioned, for transparent objects they utilised a specific recipe but it is also true that they did not usually achieve pure transparency but very close results: transparent glasses with green, blue or grey-blue hues. The majority of the Sasanian glass is colourless (with transparent unintended colours caused by impurities in the silica). There are generally yellowish-green or yellowish-brown tinges and a characteristic smoky-brown tinge frequently associated with the face-cut bowls. Whole vessels in plain colours are far less common among the Sasanians to the extent that many of the full-coloured examples are believed to be imported. They nevertheless utilised plain colour for decorative motifs. But again according to their taste, thus trails or pads tend to be delicate (See Figure 8), thin and small, (though during the early Sasanian era are usually thick) setting off the reflective and sparkling surfaces obtained by polishing or cutting, or adding spiral or vertical ribs. It is very common to find that the applications - the application of prunts of glass was especially ‘popular’ among the Sasanians (Goldstein 2005, 14)- are equally colourless, applied and pinched, giving to the vessel a spiky aspect, appropriately described by Goldstein (2005) as ‘sputnik’. (See Figures 6-7)

Significance of Sasanian glass

The Sasanian Empire ‘enjoyed a reputation for luxury in Byzantine and Arab written accounts’ (St. John Simpson 2000, 62). Not for nothing was this the setting of the Arabian Nights. Glass also reflects this situation: for example during the contraction of the production during the Byzantine period (400-616AD) ‘luxury wares were little in demand, with the exception of chip-cut vessels of the Sasanian type’ (Rogers 2005, 23, See Figure 9).

To the East, Sasanian glass was equally recognised. China named the Silk Road as the Horse Road or the Glass Road, as Sasanian glass was ‘highly appreciated’ there (Gyselen 2007, 17). Similarly in Japan, it appeared in the tombs (Shoshoin, Okinoshima, Kamigamo, etc.) of high-status nobility related to the Emperor (Roger 2005; Whitehouse 2005).

Sasanian glass had a rapid growth and distribution both within and without the borders of the Empire and was not only used in luxury items; glass objects destined for utilitarian uses spread all over the Empire (Meyer 1995) and, most important, over certain social classes that did not have access to it till that moment. The secrets of this success remain surely in the fabrication of different qualities of glass and in its style, simultaneously simple and sophisticated, creating ‘unusual products based on definite designs that differed from the East Roman patterns’ (Negro Ponzi 1968-69, 384) and in fact from all other productions manufactured at that date.

Archaeological Record

Till now, there have been no clear examples of glass workshops or of glassmaking factories. In fact excavated settlements with Sasanian glass are rather scarce: Seleucia, Tell Baruda, Ctesiphon, Veh Ardashir, Choche, Nippur, Samarra and a few more (Whitehouse 2005). A high number of the pieces have been found in funerary contexts, Tell Mahuz, Ghalekuti, Hassani Mahale, Abu Skhair, etc. A small paradox is that, although the Iranian Plateau is the core of the territory controlled by Sasanians, the archaeological record of glass production is rather meagre there, with the best examples of workshops concentrated on the borders of the empire, namely Northern Iraq (Saldern 1963 and 1966; St. John Simpson 2000; Whitehouse 2005).

This lack of archaeological finds means that most of the provenances of Sasanian glass are unknown; there are just vague notes on them like: "Eastern Roman Empire or Iran", "North-western Iraq", "Mesopotamia", "Iran or Iraq" with a large number of the vessels appearing in antiquities markets. Incidentally, this also causes the wideness of concepts among the different scholars mentioned above about what can be considered as Sasanian.

"We are a long way from a definitive picture of Islamic production through the ages". (Rogers 2005, 25)

References

- The references of Saldern and Erdmann have been taken from Whitehouse 2005, pages 10 and 30 respectively.

Bibliography

- Brill, R.H. (2005): Chemical Analyses of Some Sasanian Glasses from Iraq. Sasanian and post Sasanian glass in the Corning Museum of glass by Whitehouse, D. Corning, NY: Coring Museum of Glass, p. 65-88.

- Demange, F (2007): Glass, gilding and grand design: art of Sasanian Iran (224-642). New York: Asian Society.

- Freestone, I.C (2006): Glass production in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic period: a geochemical perspective. Geomaterials in Cultural Heritage; Maggeti, M. and Messiga, B. (ed.). Geological Society. London, Special publications 257, p. 201-216.

- Goldstein, S.M. (1980): Pre-Persian and Persian Glass: Some observations on objects in the Corning Museum of Glass. Ancient Persia: The art of an Empire, Schmandt-Besserat D. (ed.). Malibu: Undena.

- Goldstein, S.M., Rakow, L.S. and Rakow J.K. (1982): Cameo glass: masterpieces from 200 years of glassmaking. The Corning Museum of glass. Corning. New York.

- Goldstein, S.M (2005): Glass from Sasanian antecedents to European imitations. London: The Nour Foundation in association with Asimuth editions.

- Gyselen, Rika (2007): The Sasanian world. Glass, gilding and grand design: art of Sasanian Iran (224-642) by Demange, F. New York: Asian Society, p. 13-20.

- Negro Ponzi, M. (1969): A group of Mesopotamian glass Vessels of Sasanian date. Studies in glass history and design, VIIIth International Congress on Glass. London 1 – 6 July 1968. Charleston J.R, Evans W. and Werner A.E. (ed.). Old Woking, Surrey: Gresham Press.

- Negro Ponzi, M (1968–69): Sasanian glassware from Tell Mahuz (North Mesopotamia). Mesopotamia 3-4, p. 293-384.

- Negro Ponzi, M (1972): Glassware from Abu Skhair (Central Iraq). Mesopotamia 7, p. 214-233.

- Negro Ponzi, M. (1984): Glassware from Choche (Central Mesopotamia). Arabie orientale, Mésopotamie et Iran méridionale de láge du fer au début de la période islamique, R. Boucharlat and J-F Salles (ed.), Mémoire nº 37. Paris: Editions Rocherche sur les Civilisations, p. 33-40.

- Negro Ponzi, M (1987): Late Sasanian glassware from Tell Baruda. Mesopotamia 22, p. 265-275.

- Negro Ponzi, M (2002): The glassware from Seleucia (Central Iraq). Parthia nº 4, p. 63-156.

- Newman, H. (1977): An illustrated dictionary of Glass. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Meyer, C. (1996): Sasanian and Islamic glass from Nippur, Iraq. Annales du 13º Congres de l’Association International pour l’ histoire du Verre. Pays Bas / 28 aout-1 septembre 1995, p. 247-255.

- Mirti, P., Pace, M., Negro Ponzi, M. and Aceto M. (2008): ICP-MS analysis of glass fragments of Parthian and Sasanian epoch from Seleucia and Veh Ardasir (Central Iraq). Archaeometry 50 (3), p. 429-450.

- Mirti, P., Pace M., Malandrino M. and Negro Ponzi, M. (2009): Sasanian glass from Veh Ardasir: new evidence by ICP-MS analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, p. 1061-1069.

- Saldern A. (1963): Achaemenid and Sasanian cut glass. Ars Orientalis 5, pp. 7–16.

- Saldern A. (1966): Ancient glass. Boston Museum Bulletin 64 (335), pp. 4–17.

- St. John Simpson (2000): Mesopotamia in the Sasanian period. Settlement patterns, arts and crafts. Mesopotamia and Iran in the Parthian and Sasanian Periods, Rejection and Revival c. 238BC – AD 642. Curtis J. (ed.). London: British Museum Press, p. 57-66.

- Whitehouse, D (2005): Sasanian and post Sasanian glass in the Corning Museum of glass. Corning, NY: Coring Museum of Glass.

- Whitehouse, D (2006): La verrerie Sassanide. Les Perses Sassanides. Fastes d’un Empire oubli’e (224-642). Paris: Editions Findankly, 138-154.

- Whitehouse, D. (2007): Sasanian glassware. Glass, gilding and grand design: art of Sasanian Iran (224-642) by Demange, F. New York: Asian Society, p. 29-33.

- Wood, J.R. and Greenacre, M. (2021): Making the most of expert knowledge to analyse archaeological data: A case study on Parthian and Sasanian glazed pottery. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 13, p. 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01341-0

- Wood, J.R. and Hsu, Y-T. (2020): Recycling Roman glass to glaze Parthian pottery. Iraq 82, p. 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1017/irq.2020.9

- Wood, J.R. (2022): Approaches to interrogate the erased histories of recycled archaeological objects. Archaeometry https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12756

External links

- Potts, Daniel (2018). "glass, Persian". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.