Sava Temišvarac

Sava Temišvarac (Serbian Cyrillic: Сава Темишварац, "Sava of Timișoara"; fl. 1594–1612) was a Serb military commander (vojvoda) in the service of the Transylvania and then the Holy Roman Empire. He was active during the Long Turkish War, having led the Uprising in Banat (1594) and then joined the Transylvanian Army with other notable Serb leaders.

Sava Temišvarac | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Sava |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | Temeşvar, Temeşvar Eyalet, Ottoman Empire (now Romania) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1594–1612 |

| Rank |

|

| Military history | Long Turkish War |

| Awards | knighthood |

Uprising in Banat

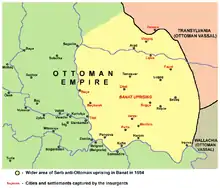

Bishop Teodor of Vršac and Sava Temišvarac led the Uprising in Banat (1594).[1] The rebels had, in the character of a holy war, carried war flags with the icon of Saint Sava.[2][3] After initial success, the rebels had by March 1594 expelled the Ottomans from almost the entire territory of Banat and Körös.[3] On 27 April, in an act of retaliation, Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha had the relics of Saint Sava incinerated at Vračar; made to discourage the Serbs, it instead intensified the rebellion.[3]

Đorđe Palotić, the Ban of Lugos, stole armament which he sent to the rebels, and encouraged them to continue to fight; he subsequently promised that the Transylvanian Duke, Sigismund Báthory, would soon appear to them.[4] Known as ban Sava at the time, he, Teodor and Velja Mironić signed and sent a letter in the name of "all spahee and knezes, all of Serbdom and Christianity", to the Transylvanian nobleman Mózes Székely, who was already at the frontier, asking for aid in the uprising,[4] to send troops as soon as possible.[5] They mentioned in the letter that 1,000 armed men were gathered in Vršac.[6] The letter was sent from Vršac on 13 June, two days after the decision at the Assembly at Gyulafehérvár.[4] However, Székely was unwilling to cross the Transylvanian border, so the Serbs were left on their own.[5]

Hasan Pasha, the beylerbey of the Temeşvar Eyalet, gained aid from the Grand Vizier and the Pasha of Budim, thus turned with an army numbering 20,000 soldiers and attacked Becskerek (Zrenjanin), in the hands of 4,300 rebels, ending in a decisive Ottoman victory.[5] Subsequently, Sinan Pasha took an army of 30,000 soldiers which suppressed the badly armed Serbs.[3] There were reprisals, contemporary sources speaking of "the living envied the dead".[3] The Serb fight for freedom and restoration of the national state was however not put to an end.[3] After the crushing of the uprising in Banat, Serbs migrated to Transylvania under the leadership of Bishop Teodor; the territory towards Ineu and Teiuș was settled, where Serbs had lived since earlier – the Serbs had their eparchies, opened schools, founded churches and printing houses.[3] In 1596–97, a Serb uprising broke out in Eastern Herzegovina.[7]

Transylvanian Army and Imperial Army

Sava was mentioned in 1596[8] during the war between Sigismund Báthory and the Ottoman Empire.[9] Báthory's army which headed to liberate Timișoara, included notable Serbs, such as Đorđe Rac, Deli-Marko, and Sava Temišvarac.[9] The army managed to conquer the Serbian part of the town.[10] These Serb leaders, including Starina Novak, fought as part of the Transylvanian Army, but carried out independent raids south of the Danube, into what is today Bulgaria and Serbia,[11] even managing to raid as deep as Plovdiv and Adrianople.[12] The Serb commanders mainly operated outside Transylvania, with the support of the Emperor.[13] The Serb soldiers and refugees were taken care of by the War Council in Vienna.[13]

In 1604, Temišvarac is mentioned as a commander of a squad in the army of General Belgioz, at the time which this army battled in the region around Timișoara.[8] In 1605, together with Deli-Marko, he left Transylvania and crossed to western Hungary.[8] The Long Turkish War ended in 1606 with the Peace of Zsitvatorok.

In 1606–07 he was a commander of Serb soldiers in Sopron.[8] In 1607, Temišvarac and the bands were relocated from Sopron to Győr.[8] Here, Temišvarac requested from the War Council to pay the soldiers the unpaid mercenary salary, and that his position be regulated.[8] In 1608 he requested rectification from the War Council, which answered that it would, in case of need, have him and his band in mind.[8] The War Council was known for unpaid salaries.[14] Emperor Rudolf II gave him the rank of colonel, but Temišvarac was not pleased, as this decision only had value in war-time when he wanted to secure a decent living in peace-time.[8] In December 1608 he made a re-request for the case.[8]

At the same time, there were great turn of events, Emperor Rudolf II started quarreling with his brother, Matthias, during which Temišvarac, Đorđe Rac and Deli-Marko supported the latter, joining with their people.[8] All mercenary bands commanded by the three Serb leaders participated in the march on Rudolf II.[15] Temišvarac's band had, during their return from the Czech lands, inflicted great damage to the population.[8] The band once again returned to Győr.[8]

The evicted Serbs from Transylvania became dissatisfied with the government after the decision that Temišvarac, who had commanded the Serbs during war-time, was prohibited to issue orders during peace-time to judges, councilors and other Serbs.[14] The Serb refugees then asked the War Council to assign them some deserted villages around Győr, in order to broaden their military frontier (krajište).[14] Temišvarac accepted the offer of Polish count Nicholas of Komorowo to join him with 200 of his cavalry.[14] This time, the Austrian government adopted to the Serb demands.[14]

Some Serb nobility accepted military service in the end of 1609, while Sava Temišvarac was sent for to Vienna in 1610 on the request of King Matthias, where he received a diploma which praised and raised his military work, when he had, as a commander of thousands of Serb cavalry, campaigned in Upper Hungary, Transylvania and the Czech lands.[14] Other Serb chiefs and captains, such as those called "Rac", also received similar diplomas.[14] Thus, the riparian lands towards the Danube, with a centre in Győr, acted as a frontier stronghold against the Ottoman threat.[14]

After Rudolf's death in 1612, Matthias was crowned Emperor, after which he, in his new right, signed the peace treaty with the Ottomans.[15]

Legacy

Sava Rac-Temišvarac was among the most notable Serbs in the history of Transylvania, along with Jovan Rac, Adam Rac, bishop Sava Branković and count Đorđe Branković, among others.[16]

See also

References

- Čedomir Marjanović (2001). Istorija Srpske crkve. Ars Libri. p. 178. ISBN 9788675880011.

- Nikolaj Velimirović (January 1989). The Life of St. Sava. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-88141-065-5.

- Cerović 1997, Oslobodilački pokreti u vreme Turaka.

- Samardžić et al. 1993, p. 245.

- Karlovačka mitropolija 1910, p. 45

Али Секељ не хтеде ни сада прећи ердељску границу, већ остави Србе њиховој судбини. Беглербег темишварски Хасан добије помоћи од великог везира и од будимског паше, те са војском од 20.000 душа нападне код Бечкерека српске устанике, којих је било на 4300 душа. Битка се брзо свршила са потпуним поразом ...

- Popović 1990, p. 302.

- Samardžić et al. 1993, p. 324.

- Kolundžija 2008, p. 251.

- Popović 1990, p. 184.

- Etnografski institut (1952). Posebna izdanja. Vol. 4–8. Naučno delo. p. 199.

- Slavko Gavrilović (1993). Iz istorije Srba u Hrvatskoj, Slavoniji i Ugarskoj: XV-XIX vek. Filip Višnjić. p. 17. ISBN 9788673631264.

- Даница: српски народни илустровани календар за годину ... Вукова задужбина. 2008. p. 477.

- Samardžić et al. 1993, p. 277.

- Samardžić et al. 1993, p. 280.

- Samardžić et al. 1993, p. 279.

- Matica srpska; Tihomir Ostojić; Jovan Radonić (1929). Knjige. Vol. 50. Novi Sad. pp. 252–253.

Од ерделских Срба из овог доба заслужу^у спешена ЛованРац-Тохол>евиЬ-Смедеревац, Сава Рац-Темишварац, Адам Рац од Галго-а, епископ Сава БранковиН и брат му ЪорЬе БранковиЬ.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Sources

- Popović, Dušan J. (1990). Srbi u Vojvodini. Matica srpska. ISBN 9788636301746.

Сава Темишварац

- Kolundžija, Zoran (2008). Vojvodina: Od najstarijih vremena do velike seobe. Prometej. ISBN 9788651503064.

- Karlovačka mitropolija (1910). Srpska pravoslavna mitropolija karlovačka: po podacima od 1905. Saborski odbor.

- Cerović, Ljubivoje (1997). "Srbi u Rumuniji od ranog srednjeg veka do današnjeg vremena". Projekat Rastko. Archived from the original on 2013-06-14.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Veselinović, Rajko L.; Popović, Toma (1993). Radovan Samardžić (ed.). Istorija srpskog naroda. Treća knjiga, prvi tom: Srbi pod tuđinskom vlašću 1537-1699. Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.