Scarab (artifact)

Scarabs are beetle-shaped amulets and impression seals which were widely popular throughout ancient Egypt. They still survive in large numbers today. Through their inscriptions and typology, they prove to be an important source of information for archaeologists and historians of the ancient world, and represent a significant body of ancient Egyptian art.

_MET_27.3.245_bot.jpg.webp)

Likely due to their connections to the Egyptian god Khepri, amulets in the form of scarab beetles had become enormously popular in Ancient Egypt by the early Middle Kingdom (approx. 2000 BCE) and remained popular for the rest of the pharaonic period and beyond. Throughout Egyptian history, the function of scarabs repeatedly changed. Though primarily worn as amulets and sometimes rings, scarabs were also inscribed for use as personal or administrative seals or were incorporated into other kinds of jewelry. Additionally, some scarabs were created for political or diplomatic purposes to commemorate or advertise royal achievements.

Starting in the middle Bronze Age, other ancient peoples of the Mediterranean and the Middle East imported scarabs from Egypt and also produced scarabs in Egyptian or local styles, especially in the Levant.

By the end of the First Intermediate Period (about 2055 BCE) scarabs had become extremely common. They largely replaced cylinder seals and circular "button seals" with simple geometric designs. Throughout the period in which they were made, scarabs were often engraved with the names of pharaohs and other royal figures. In the Middle Kingdom, scarabs were also engraved with the names and titles of officials, to be used as official seals. From the New Kingdom, scarabs bearing the names and titles of officials became rarer, while scarabs bearing the names of gods, often combined with short prayers or mottos became more popular, though these scarabs are somewhat difficult to translate.

Description

Scarabs were typically carved or molded in the form of a scarab beetle (usually identified as Scarabaeus sacer) with varying degrees of naturalism but usually at least indicating the head, wing case and legs but with a flat base. The base was usually inscribed with designs or hieroglyphs to form an impression seal. They were usually drilled from end to end to allow them to be strung on a thread or incorporated into a swivel ring. The common length for standard scarabs is between 6 mm and 40 mm and most are between 10 mm and 20 mm. Larger scarabs were made from time to time for particular purposes, such as the commemorative scarabs of Amenhotep III.

Scarabs were generally either carved from stone, or molded from Egyptian faience, a type of Ancient Egyptian sintered-quartz ceramic. Once carved, they would typically be glazed blue or green and then fired. The most common stone used for scarabs was a form of steatite, a soft stone that becomes hard when fired (forming enstatite). In contrast, hardstone Scarabs most commonly were composed of green jasper, amethyst and carnelian.

While the majority of Scarabs would originally have been green or blue, much of the colored glazes have become discolored or erased by the elements over time, leaving most steatite scarabs appearing white or brown.

Religious significance

In ancient Egypt, the Scarab Beetle was a highly significant symbolic representation of the divine manifestation of the morning sun.

The Egyptian god Khepri was believed to roll the sun across the sky each day at daybreak. In a similar fashion, some beetles of the family Scarabaeidae use their legs to roll dung into balls. Because of its symbolically similar action, the scarab was seen as a reflection of the heavenly cycle and was characterized as representing the idea of rebirth or regeneration.

The scarab has ties to themes of manifestation and growth, and scarabs have been found all across Egypt which originate from many different periods in Egyptian history. scarabs have also been found inside of sunken ships, like one discovered in Uluburun, Turkey, which was inscribed with the name of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti.

Commemorative scarabs

Amenhotep III (the immediate predecessor of Akhenaten) is famed for having commemorative scarabs manufactured. These were large (mostly between 3.5 cm and 10 cm long) and made of steatite, a grayish-green or brown colored talc. These scarabs were intricately crafted, created under royal supervision, and carried lengthy inscriptions describing one of five important events in his reign (all of which mention his queen, Tiye). More than 200 of these have survived, and the locations in which they have been discovered suggest they were sent out as royal gifts and propaganda in support of Egyptian diplomatic activities. The crafting of these large scarabs was a continuation of an earlier Eighteenth Dynasty tradition of making scarabs to celebrate specific royal achievements, such as the erection of obelisks at major temples during the reign of Thuthmosis III. This tradition was revived centuries later during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, when the Kushite pharaoh Shabaka (721–707 BCE) had large scarabs made to commemorate his victories in imitation of those previously produced for Amenhotep III.

Funerary scarabs

.jpg.webp)

Scarab amulets were sometimes placed in tombs as part of the deceased's personal effects or jewelry, though not all scarabs had an association with ancient Egyptian funerary practices. There are, however, three types of scarabs, heart scarabs, pectoral scarabs and naturalistic scarabs, that seem to be specifically related to ancient Egyptian funerary practices.

Heart scarabs became popular in the early New Kingdom and remained in use until the Third Intermediate Period. They are typically 4 cm-12 cm long, and are often made from dark green or black stone not pierced for suspension. Heart scarabs were often hung around the mummy's neck with a gold wire and the scarab itself was held in a gold frame. The base of a heart scarab was usually carved, either directly or on a gold plate fixed to the base, with hieroglyphs which name the deceased and repeat some or all of spell 30B from the Book of the Dead. The spell commands the deceased's heart (typically left in the mummy's chest cavity, unlike the other viscera) not to give evidence against the deceased when he/she is being judged by the gods of the underworld. It is often suggested that the heart is being commanded not to give false evidence, but the opposite may be true.

From the Twenty-fifth Dynasty onwards, large (typically 3–8 cm long), relatively flat uninscribed pectoral scarabs were sewn together with a pair of separately made outstretched wings, onto the chests of mummies via holes formed at the edge of the scarab. Pectoral scarabs appear to be associated with the god Khepri, who is often depicted in the same form.

Naturalistic scarabs are relatively small (typically 2 cm to 3 cm long), made from a wide variety of hardstones and Egyptian Faience, and are distinguished from other scarabs by their naturalistic carved three dimensional bases, which often also include an integral suspension loop running widthways. Groups of these funerary scarabs, often made from different materials, formed part of the battery of amulets which were believed by ancient Egyptians to protect mummies throughout the Late Period.

Ancient Egyptians believed that when a person died and underwent their final judgement, the gods of the underworld would ask many detailed and intricate questions which had to be answered precisely and ritually, according to the Book of the Dead. Since many ancient Egyptians were illiterate, even placing a copy of this scroll in their coffin would not be enough to protect them from judgment for giving a wrong answer. As a result, the priests would read the questions and their appropriate answers to the Beetle, which would then be killed, mummified, and placed in the ear of the deceased. It was believed that when the gods then asked their questions, the ghostly Scarab would whisper the correct answer into the ear of the supplicant, who could then answer the gods wisely and correctly.

Scarabs with royal names

Scarabs are often found inscribed with the names of pharaohs and more rarely with the names of their queens and other members of the royal family. Generally, there is a correlation between how long a king or queen ruled and how many scarabs have been found bearing one or more of their names. Famously, a golden scarab of Nefertiti was discovered in the Uluburun ship wreck.

.jpg.webp)

Most scarabs bearing a royal name can reasonably be dated to the period in which the person named lived. However, there are a number of important exceptions. scarabs have been found bearing the names of pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (particularly of well-known kings such as Khufu, Khafre and Unas). It is now believed these were produced in later periods, most probably during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty or Twenty-sixth Dynasty, when there was considerable interest in and imitation of the works of well-established kings of the past.

Scarabs have also been found in vast numbers bearing the throne name of the New Kingdom King Thuthmosis III (1504–1450 BCE) Men Kheper Re. Many of these scarabs date from the long and successful reign of this warrior pharaoh or shortly thereafter, but the majority do not. Like all pharaohs, Thuthmosis was regarded as a god after his death. Unlike most pharaohs, his cult, centered on his mortuary temple, seems to have continued for years, if not centuries. As a result, many scarabs bearing the inscription Men Kheper Re are likely to commemorate Thuthmosis III but may have been produced hundreds of years later. Later pharaohs adopted the same throne name (including Piye of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, 747–716 BCE) leading to some confusion. The hieroglyphs making Men Kheper Re seem to have become regarded as a protective charm in themselves and were inscribed on scarabs without any specific reference to Thuthmosis III. It can be doubted that in many cases the carver understood the meaning of the inscription but reproduced it blindly. On a lesser scale the same may be true of the throne name of Rameses II (1279–1212 BCE) User Maat Re ("the justice of Ra is powerful"), which is commonly found on scarabs which otherwise do not appear to date from his reign.

The birth names of pharaohs were also popular names among private individuals and so, for example, a scarab simply bearing the name "Amenhotep" need not be associated with any particular king who also bore that name.

The significance of a scarab bearing a royal name is unclear and probably changed over time and from scarab to scarab. Many may simply have been made privately in honor of a ruler during or after his lifetime. Some may also have been royal gifts. In some cases, scarabs with royal names may have been official seals or badges of office, perhaps connected with the royal estates or household. Others, although relatively few, may have been personal seals owned by the royal individual named on them. As the king fulfilled many different roles in ancient Egyptian society, so scarabs naming a pharaoh may have had a direct or indirect connection with a wide range of private and public activities.

Scarab rings

From the late Old Kingdom onwards, scarab rings developed from simple scarabs tied to fingers with threads into rings with scarab bezels in the Middle Kingdom, and further into rings with cast scarabs in the New Kingdom, typically strung on gold wire rather than string. Bezels emerged during the Old Kingdom period, often as amulets which were meant to represent Ra, the Egyptian solar god. Scarabs used for jewelry and rings were often composed of glazed steatite, which was a popular medium in ancient Egypt, though the glaze on many of these rings has been eroded over time due to weathering.

Literary and Popular Culture Reference

- P. G. Wodehouse's first Blandings novel – Something Fresh (1915) – involves the pilfering of a rare Egyptian scarab (a "Cheops of the Fourth Dynasty") as a key plot device.

- In British crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers's novel Murder Must Advertise a catapulted scarab is the murder weapon.

- The rock band Journey uses various types of scarabs as their main logo and in the cover art of the albums Departure, Captured, Escape, Greatest Hits, Arrival, Generations, Revelation, and The Essential Journey.

- The Dutch print-maker M. C. Escher (1898–1972) created a wood engraving in 1935 depicting two scarabs or dung beetles.

- In Stephen Sommers' The Mummy (1999), the scarab is used as a deadly, ancient beetle that eats the internal and external organs, killing whom ever it comes into contact with.

- In The Twilight Zone episode Queen of the Nile, the main character Pamela Morris has an ancient scarab beetle amulet that can drain the youth of anyone she places it on, enabling her to remain young forever. Morris tells her final victim that she got it from "the pharaohs, who understood its power."

- In Disney's animated movie Aladdin, the location of the Cave of Wonders is revealed when two halves of a scarab beetle are joined together.

- Scarabs are used as the monetary unit of planet Sauria (originally known as Dinosaur Planet) in the 2002 video game Star Fox Adventures.

- Scarabs appear in droves in Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation. They deal damage to Lara Croft throughout the game.

Scarabs with Inscriptions

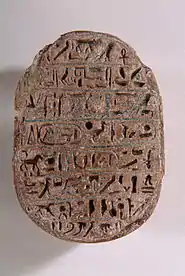

Back of scarab amulet

Back of scarab amulet Amulets: scarab and Papyrus

Amulets: scarab and Papyrus Scarab with a cartouche

Scarab with a cartouche.png.webp) Scarab: top, and engravings.

Scarab: top, and engravings. Signet ring, with cartouche of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun:

Signet ring, with cartouche of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun:

'Perfect God, Lord of the Two Lands' – ('Neter-Nefer, Neb-taui') Faience pectoral scarab with spread wings, The Walters Art Museum.

Faience pectoral scarab with spread wings, The Walters Art Museum. Faience pectoral scarab with spread wings and bead net, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate

Faience pectoral scarab with spread wings and bead net, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate A modern scarab produced for the tourist trade.

A modern scarab produced for the tourist trade. Amenophis III lion hunt scarab – top view, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate

Amenophis III lion hunt scarab – top view, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate Amenophis III lion hunt scarab – base view, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate

Amenophis III lion hunt scarab – base view, Royal Pump Room, Harrogate A pendant in the shape of a winged scarab carrying the Eye of Horus, from the treasury of Tut's tomb

A pendant in the shape of a winged scarab carrying the Eye of Horus, from the treasury of Tut's tomb

Sources

- Andrews, Carol, 1994. Amulets of Ancient Egypt, chapter 4: Scarabs for the living and funerary Scarabs, pp. 50–59, Andrews, Carol, 1993, University of Texas Press; (softcover, ISBN 0-292-70464-X)

- "Ancient Egyptian Scarab Amulet with Wings". australianmuseum.net.au. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Ben-Tor, Daphna. "Egyptian-Levantine Relations And Chronology In The Middle Bronze Age: Scarab Research." The Synchronisation Of Civilisations In The Eastern Mediterranean In The Second Millennium B.C. II. N.p.: n.p., n.d. 239". Academia.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Blankenberg-van Delden, C., 1969. The large commemorative Scarabs of Amenhotep III. Documenta et Monumenta Orientis Antiqui, Vol. 15. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-00474-0.

- Budge, 1977, (1926). The Dwellers on the Nile, E. A. Wallis Budge, (Dover Publications), c 1977, (originally, c 1926, by Religious Tract Society, titled as: The Dwellers on the Nile: Chapter of the Life, History, Religion and Literature of the Ancient-Egyptians); pp 265–268: "account of the hunting of wild cattle by Amenhetep III", "taken from a great Scarab"; (there are 16 registers-(lines) of hieroglyphs); (softcover, ISBN 0-486-23501-7)

- Evans, Elaine A. (17 April 1997). "Sacred Scarab". McClung Museum. N.p. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Kerrigan, Michael. "Tiy's Wedding Scarab." The Ancients in Their Own Words. N.p.: Fall River, 2009. 54–55. Print.

- Newberry, Percy E. (1908). Scarabs: an introduction to the study of Egyptian seals and signet rings. University of Liverpool. Institute of archaeology. Egyptian antiquities. London: Archibald Constable & Co; With forty-four plates and one hundred and sixteen illustrations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Patch, Diana Craig. "Exhibitions: Magic in Miniature: Ancient Egyptian Scarabs, Seals & Amulets". Brooklyn Museum Archive, n.d. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Schulz, R., Seidel, M. Egypt, The World of the Pharaohs, Eds. Regine Schulz and Matthias Seidel, (w/ 34 contributing Authors), (Konemann, Germany), c 1998. ( 2 ) Scarab seals, (as impression seals), (Top/Bottom, 1.5 cm), and "Commemorative Scarab" of Amenhotep III, (Top/Bottom hieroglyphs), p. 353. (hardcover, ISBN 3-89508-913-3)

- Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina. "Ancient Egyptian Seals and Scarabs". The Ancient Seals. Torino, Italy: n.p., 2009. N. pag.: academia.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "Stamp Scarab Seal with Winged Figures [Levant or Syria] (Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty 1941 (41.160.162))". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Ward, John, and F. L. Griffith. The Sacred Beetle: A Popular Treatise on Egyptian Scarabs in Art and History. Five hundred examples of Scarabs and cylinders, the translations by F. Llewellyn Griffith. London: John Murray, 1902. OCLC 1853124

External links

- 1.1 cm Scaraboid impression seal. Hapy, Nile god holding Water-vessel, and kneeling on hieroglyph for "Lord", "Lord of the Nile". (Click on picture. Top, and bottom views.)

- 'Positive-impression' cowrie-Scaraboid. Collection of Ten Scaraboid seals. (Click on picture. Top, and bottom views.)

- Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains a significant amount of material on Scarabs (see index)

- Scarab Beetles and the people of Ancient Egypt Great video on Scarab Beetles.

- Heart Scarab Amulet Picture of a Heart Scarab Amulet from the British Museum