Scelidosaurus

Scelidosaurus (/ˌsɛlɪdoʊˈsɔːrəs/; with the intended meaning of "limb lizard", from Greek skelis/σκελίς meaning 'rib of beef' and sauros/σαυρος meaning 'lizard')[1] is a genus of herbivorous armoured ornithischian dinosaur from the Jurassic of the British Isles (specifically England and Ireland).

| Scelidosaurus | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scelidosaurus cast of the David Sole specimen BRSMG LEGL 0004, in Utah. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Saphornithischia |

| Clade: | †Genasauria |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Genus: | †Scelidosaurus Owen, 1859 |

| Species: | †S. harrisonii |

| Binomial name | |

| †Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen, 1861 | |

Scelidosaurus lived during the Early Jurassic Period, during the Sinemurian to Pliensbachian stages around 191 million years ago. This genus and related genera at the time lived on the supercontinent Laurasia. Its fossils have been found in the Charmouth Mudstone Formation near Charmouth in Dorset, England, and these fossils are known for their excellent preservation. Scelidosaurus has been called the earliest complete dinosaur.[2][3] It is the most completely known dinosaur of the British Isles. Scelidosaurus is currently the only classified dinosaur found in Ireland. Despite this, a modern description only materialised in 2020. After initial finds in the 1850s, comparative anatomist Richard Owen named and described Scelidosaurus in 1859. Only one species, Scelidosaurus harrisonii named by Owen in 1861, is considered valid today, although one other species was proposed in 1996.

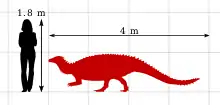

Scelidosaurus was about 4 metres (13 ft) long. It was a largely quadrupedal animal, feeding on low scrubby plants, the parts of which were bitten off by the small, elongated head to be processed in the large gut. Scelidosaurus was lightly armoured, protected by long horizontal rows of keeled oval scutes that stretched along the neck, back and tail.

One of the oldest known and most "primitive" of the thyreophorans, the exact placement of Scelidosaurus within this group has been the subject of debate for nearly 150 years. This was not helped by the limited additional knowledge about the early evolution of armoured dinosaurs. Today most evidence suggests that Scelidosaurus is the most derived of the known basal thyreophorans, either closely related to Ankylosauria or Stegosauria+Ankylosauria.

Description

Size and posture

A full-grown Scelidosaurus was rather small compared to most later non-avian dinosaurs, but it was a medium-sized species in the Early Jurassic. Some scientists have estimated a length of 4 metres (13 ft).[4] In 2010, Gregory S. Paul gave a body length of 3.8 metres (12.5 ft) and a weight of 270 kg (600 lb).[5] Scelidosaurus was quadrupedal, with the hindlimbs longer than the forelimbs. It may have reared up on its hind legs to browse on foliage from trees, but its arms were relatively long, indicating a mostly quadrupedal posture.[6] A trackway from the Holy Cross Mountains of Poland shows a scelidosaur like animal walking in a bipedal manner, hinting that Scelidosaurus may have been more proficient at bipedalism than previously thought.[7]

Distinguishing traits

The first modern diagnosis was provided by David Bruce Norman in 2020. In a first article, Norman provided autapomorphies, unique derived characters, of the skull. The front snout bones, the premaxillae, have a common central rough extension, in life bearing a small upper beak. The nasal bone has on its upper outside a facet touching the inner side of the ascending branch of the premaxilla. The antorbital fenestra is present as a bean-shaped depression, its lower edge formed by a sharp ridge. The central parietal crest on the skull roof is formed by two parallel crests separated by a narrow trough on the midline. The roof of the nasal cavity is formed by special plates above the vomers, called the "epivomers". The epipterygoid bone is shaped as a small conical vertical structure of which the base connects to the upper side of the pterygoid bone by means of a lateral flat surface. The basioccipital has large oblique facets on the lower sides. The opisthotic has an expanded pedicel with facets on its underside. Elongated epistyloid bones project obliquely to the rear and below, from the back of the skull. A small spur-like structure on the upper edge of the paroccipital process encases the posttemporal fenestra. The rear of the skull is fused on its upper edge with a pair of large curved horn-shaped osteoderms. The lower jaw shows only little exostosis, limited to the angular, and lacking an attached osteoderm.[8]

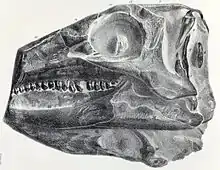

Skull

The head of Scelidosaurus was small, about twenty centimetres long, and elongated. The skull was low in side view and triangular in top view, longer than it was wide, similar to that of earlier ornithischians. The snout, largely formed by the nasal bones, was flat on top. Scelidosaurus still had the five pairs of fenestrae (skull openings) seen in basal ornithischians: apart from the nostrils and eye sockets which are present in all basal dinosaurs, the fenestra antorbitalis and the upper and lower temporal fenestrae were not closed or overgrown, as with many later armoured forms. In fact, the upper temporal fenestrae were very large, forming conspicuous round openings in the top of the rear skull, serving as attachment areas for the powerful muscles that closed the lower jaws. The eye socket was slightly overshadowed in its front part by a brow ridge that has been seen as the prefrontal bone. In 2020, Norman concluded that it was a fused palpebral bone.[8] Behind it, the upper rim of the eye socket was formed by the supraorbital bone. A study by Susannah Maidment e.a. concluded that juvenile specimens show that this bone was a fusion of three elements, one in front, the next in rear, and the third at the inner side.[9]

The premaxilla, the bone forming the snout tip, was short and no predentary, the bone core of the lower beak on the tip of the stout lower jaws, has been found, so the horny beak that is assumed present with all ornithischians was likely very short. Its teeth were longer and more triangular in side view than in later armoured dinosaurs.[10] There were at least five teeth in each premaxilla, and at least nineteen in the maxilla and sixteen in the dentary of the lower jaw.[6] However, the number of maxillary and dentary teeth were established with the incomplete skull of one of the first specimens found; the actual numbers might have ranged up to about two dozen, perhaps twenty-six for the lower jaw. The premaxillary teeth were somewhat longer and recurved. To the rear, they gradually approach the form of the maxillary teeth, beginning to show denticles. The crowns of the maxillary and dentary teeth have denticles on their edges and a swollen basis[6]

The ascending branches of the paired premaxillae notched the combined nasal bones, whereas the opposite was usual in ornithischians. The frontal bones were covered by a halo of fine ridges; these indicate the presence of keratinous plates, as with modern turtles. At the front of the braincase, paired hatchet-shaped ossified orbitosphenoids formed the floor of the olfactory lobes of the brain. The skull of the lectotype was damaged by a paleoichthyologist resulting in the detachment of triangular plates from the palate. These elements had been sketched by Norman in the seventies prior to the incident and interpreted as parts of the pterygoids, but in 2020 he concluded that they were special bones covering the roof of the nasal cavity, which he named the "epivomers". These are not known from any other animal.[8]

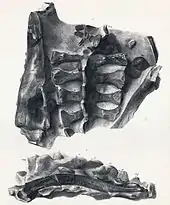

Postcranial skeleton

The vertebral column of Scelidosaurus contained at least six neck vertebrae, seventeen dorsal vertebrae, four sacral vertebrae and at least thirty-five tail vertebrae.[6]

Though perhaps the actual total of cervical vertebrae was as high as seven or eight, the neck was only moderately long. The torso was relatively flat in side view, however, despite the belly being broad, it was not extremely vertically compressed as with ankylosaurs but taller than wide. The last three dorsal vertebrae had no ribs. The spines of the sacral vertebrae touched each other but were not fused into a supraneural plate. The quickly tapering tail was relatively short, probably representing about half of body length. The tail chevrons were strongly inclined to the rear. The hip area and tail base were stiffened by large numbers of ossified tendons.[6]

The scapula was short with a moderately expanded upper end. The coracoid was circular in side view. The elements of the forelimb were generally moderately long, straight and stout. The hand is only known from recent discoveries and has not yet been described. In the rather wide pelvis, the ilium was straight in side view. Its front blade was rod-shaped and moderately splayed to the outside, creating room for the belly. This was reinforced by the sacral ribs becoming longer towards the front. The sacral ribs were wider at their attachment areas with the ilium, but were not fused into a sacral yoke. The pubis featured a short prepubis. The pubis shaft was straight, running parallel to a straight ischium shaft that was transversely flattened at its lower end. The thighbone was straight in side view, in front view it was somewhat bowed to the outside. Its head was not separated from the shaft by a real neck. While the major trochanter was at about the same level as the head, the lower minor trochanter was separated from both by a deep cleft. At it rear side, the femur mid-shaft featured a well-developed drooping fourth trochanter, a process for the attachment of the retractor tail muscle, the Musculus caudofemoralis longus. The lower leg was somewhat shorter than the thighbone. The tibia had a wide upper end, with a cnemial crest protruding well to the front. The tibia lower end was also robust and rotated about 70° compared to the upper part, turning the foot strongly to the outside. The foot was very large and wide. The fifth metatarsal was only rudimentary but the other four were robust. Scelidosaurus had four large toes, with the innermost digit being the smallest. The fourth metatarsal was short but its toe was long and built to be splayed to the outside of the foot, to improve the stability. The claws were flat, hoof-shaped and curved to the inside.[6]

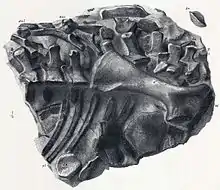

Armour

The most obvious feature of Scelidosaurus is its armour, consisting of bony scutes embedded in the skin. These osteoderms were arranged in horizontal parallel rows down the animal's body.[4] Osteoderms are today found in the skin of crocodiles, armadillos and some lizards. The osteoderms of Scelidosaurus ranged in both size and shape. Most were smaller or larger oval plates with a high keel on the outside, the highest point of the keel positioned more to the rear. Some scutes were small, flat and hollowed-out at the inside. The larger keeled scutes were aligned in regular horizontal rows. There were three rows of these along each side of the torso. The scutes of the lowest, lateral, row were more conical, rather than the blade-like osteoderms of Scutellosaurus.[11] Between these main series, one or two rows of smaller oval keeled scutes were present. There were in total four rows of large scutes on the tail: one at the top midline, one at the midline of the underside, and one at each tail side. Whether the midline tail scutes continued over the torso and neck to the front is unknown and unlikely for the neck, though Scelidosaurus is often pictured this way.

The neck had at each side two rows of large scutes. The osteoderms of the lower neck row were very large, flat and plate-like. The first osteoderms of the top neck rows formed a pair of unique three-pointed scutes directly behind the head. These points seem to have been connected by tendons to the rear joint processes, the postzygapophyses, of the axis vertebra.[6] In general the scutes were larger at the front of the torso, the osteoderms diminishing towards the rear, especially on the surface of the thighs. The smallest flat round scutes might have filled the room between the larger osteoderm rows. Perhaps a row of vertical osteoderms was present on the upper arms. Compared to the later Ankylosauria, Scelidosaurus was lightly armoured, without continuous plating, spikes or pelvic shield. Rough areas on the skull and lower jaws indicate the presence of skin ossifications.

Some of the latest specimens found show partly different osteoderms including scutes on which the keel is more like a thorn or spike. These specimens also seem to have little horns on the rear corners of the head, placed on the squamosal bones.[12]

Fossilized skin impressions have also been found. Between the bony scutes, Scelidosaurus had rounded non-overlapping scales like the present Gila monster.[4] Between the large scutes, very small (5-10 millimetres [0.2-0.4 in]) flat "granules" of bone were perhaps distributed within the skin. In the later Ankylosauria, these small scutes may have developed into larger scutes, fusing into the multi-osteodermal plate armour seen in genera such as Ankylosaurus.[11]

History of study

Discovery, naming, and type specimens

During the 1850s, quarry owner James Harrison of Charmouth, West Dorset of England found fossils from the cliffs of Black Ven between Charmouth and Lyme Regis, that were quarried, possibly for raw material for the manufacture of cement. Some of these he gave to the collector and retired general surgeon Henry Norris. In 1858, Norris and Harrison sent some fragmentary limb bones to Professor Richard Owen of the British Museum (Natural History), London (today the Natural History Museum). Among them was a left thighbone, specimen GSM 109560. In 1859, Owen named the genus Scelidosaurus in an entry about palaeontology in the Encyclopædia Britannica.[13] The lemma text contained a diagnosis, implicating that the genus was validly named and was not a nomen nudum, despite the fact that the definition was vague and no specimens were identified.[14] Owen intended to call the dinosaur "hindlimb saurian" but confused the Greek word σκέλος, skelos, "hindlimb", with σκελίς, skelis, "rib of beef".[15][16] The name was inspired by the strong development of the hind leg. Afterwards Harrison sent a knee joint, a claw (GSM 109561), a juvenile specimen and a skull to Owen, that were described in 1861. On that occasion the type species Scelidosaurus harrisonii was named, the specific name honouring Harrison.[15] The skull later was revealed to be part of a nearly complete skeleton, that was described by Owen in 1863.[17]

British palaeontologist David Bruce Norman has stressed how remarkable it is that Owen, who previously had propounded that dinosaurs were active quadrupedal animals, largely neglected Scelidosaurus though it could serve as a prime example of this hypothesis and its fossil was one of the most complete dinosaurs found at that time. Norman explained this by Owen's excessive workload in this period, including several administrative functions, polemics with fellow-scientists and the study of a large number of even more interesting newly discovered extinct animals, such as Archaeopteryx.[18] Norman also pointed out that Owen in 1861 suggested a lifestyle for Scelidosaurus that is very different from present ideas: it would have been a fish-eater and partially sea-dwelling.[2][15]

Owen had not indicated a holotype. In 1888, Richard Lydekker while cataloguing the NHMUK fossils, designated some of the hindlimb fragments described in 1861, specimen NHMUK 39496 consisting of a lower part of a femur and an upper part of the tibia and fibula, together forming a knee joint, as the type specimen, hereby implicitly choosing them as the lectotype of Scelidosaurus. Lydekker gave no reason for this choice;[19] perhaps he was motivated by their larger size. Unfortunately, mixed in with the Scelidosaurus fossils had been the partial remains of a theropod dinosaur and the femur and tibia thus belonged to such a carnivore; this was not discovered until 1968 by Bernard Newman.[20] The same year, B. H. Newman suggested to have Lydekker's selection of the knee joint as the lectotype officially rescinded by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, as the joint was in his opinion from a species related to Megalosaurus. Eventually, after Newman had already died, Alan Jack Charig actually filed a request in 1992.[14] In 1994 the ICZN reacted positively, in Opinion 1788 deciding that the skull and skeleton, specimen NHMUK R.1111, would be the new lectotype of Scelidosaurus.[21] The knee joint was in 1995 by Samuel Welles et al. informally assigned to a "Merosaurus", which name has not yet been validly published.[22] It more likely belongs to some member of the Coelophysoidea or Neoceratosauria.[23] It has also been established by Newman and confirmed by Roger Benson that the original left thighbone, GSM 109560, belonged to a theropod.[23]

The new lectotype skeleton had been uncovered in the Black Ven Marl or Woodstone Nodule Bed, marine deposits of the Charmouth Mudstone Formation, dating from the late Sinemurian stage, about 191 million years ago.[24] It consists of a rather complete skeleton with skull and lower jaws. Only the snout tip, the neck base, the forelimbs and the tail end are missing. Hundreds of osteoderms were found in connection with the skeleton, many more or less in their original position. From the 1960s onward, this fossil was further prepared by Ronald Croucher using acid baths to free the bones from the surrounding matrix, a method perfected for the Charmouth fossils. In 1992, Charig reported that only a single block had yet to be treated,[14] but he died before the results could be published. Norman, who intended to complete this task, had revealed some new anatomical details in 2004.[6] Apart from these, a modern description was largely lacking.[24] In 2020, Norman published articles on the skull and the postcrania, also taking later finds into account. It transpired that the acid baths had, through leakages, severely deteriorated the condition of the bones, further mishandling leading to breakage and crumbling.[8]

Additional specimens

Apart from the lectotype, other fossils are known of Scelidosaurus. In 1888 Lydekker catalogued a large number of single bones, largely limb elements, and osteoderms, that had been acquired by the NHMUK from the Norris collection.[19] Owen in 1861 described a second, partial, skeleton of a juvenile animal, that later was added to the collection of Elizabeth Philpot and today is registered in the Lyme Regis Museum as specimen LYMPH 1997.37.4-10. As it was relatively large, Owen speculated, in the context of its presumed marine lifestyle, that Scelidosaurus might have been ovoviviparous.[15] The short prepubis in this specimen convinced scientists that this process did not represent the main pubic body as some had thought, who had been unable to believe that the thin, backward-pointing, pubis with the Ornithischia was homologous to the forward-pointing much larger pubic bone in most reptilian groups.

In more recent times, new discoveries have been made at Charmouth, not through commercial quarrying but by the efforts of amateur palaeontologists. In 1968 a second partial juvenile skeleton was described, specimen NHMUK R6704,[25] that had already been reported in 1959.[26] Found by geologist James Frederick Jackson (1894-1966) of Charmouth, it is from a slightly younger layer, the Stonebarrow Marl Member dating to the early Pliensbachian, about 190 million years old.[24] In 1985 Simon Barnsley, David Costain and Peter Langham excavated a partial skeleton including a very complete skull and skin impressions,[27] which was sold to the Bristol Museum where it is registered as specimen BRSMG CE12785. Specimen CAMSMX.39256 is part of the collection of the Sedgwick Museum at Cambridge.[24] Several specimens remain undescribed because they are in private collections. These include a 3.1 metres (ten feet) long skeleton found by David Sole in 2000, perhaps the most complete non-avian dinosaur exemplar ever discovered in the British Isles. All elements of the skeleton are now known.[24] The finds by Sole differ from the lectotype in details of the armour and might represent a separate taxon or reflect sexual dimorphism.[12] In 2020, Norman denied this.[8]

Between the years 1980 and 2000, three fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in Northern Ireland by palaeontologist Roger Byrne. Exact geologic provenance is not reported for any of the specimens, but the very dark colouration of the specimens indicate (through means of comparison to marine fossils in other Northern Irish localities) they hail from Lias Group rocks, likely from either the Planorbis Zone or the Pre-planorbis Zone of the Waterloo Mudstone Formation. The specimens include BELUM K3998, a proximal femur fragment discovered in January 1980; BELUM K12493, the fragment of a tibia shaft discovered in April 1981; and BELUM K2015.1.54, a small pentagonal object discovered in 2000. Histologist Robin Reid recognized the first specimen as dinosaurian due to its bone texture and structure, and reported it in 1989, suspecting it belonged to Scelidosaurus or a similar animal. Byrne then recognized the tibia specimen as dinosaurian using similar identifiers; it was assumed, based on association, the two specimens came from the same animal. The pentagonal specimen was then assumed to be a scelidosaur osteoderm on the same logic.[28]

These Irish specimens, alongside another discovered by fossil collector William Gray sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century, were formally studied by Michael J. Simms and colleagues and a study was published on them in the journal Proceedings of the Geologists' Association in December 2021. The assignment of the femoral fragment was upheld, with a clear ornithischian identity and with size and morphology specifically very similar to Scelidosaurus and unlike close relative Scutellosaurus. However, the tibia was reinterpreted as that of an indeterminate neotheropod, the pentagonal object as a mere piece of basalt resembling a fossil, and Grey's specimen as belonging to an ichthyosaur. The scelidosaur femur and theropod tibia are the only known remains of dinosaurs from Ireland, which has a poor Mesozoic fossil record entirely consisting of marine localities, and the scelidosaur specimen was the first ever reported from the island.[28]

In 2000, David Martill et al. announced the preservation of soft tissue in a specimen referred to a cf. Scelidosaurus sp. (that is, material tentatively referred to the genus Scelidosaurus but not to any specific species). The fossil, with inventory number BRSMG CF2781, was in the early 1990s, in an already prepared state, discovered in the legacy of the late Professor John Challinor, who had used it to illustrate his lectures. Its provenance is unknown. It consists of a series of eight caudal vertebrae in a cut slab of carbonate mudstone, which was judged to date from the late Hettangian to Sinemurian stages. Parts of the fossil were preserved in such a way that an envelope of preserved soft tissue is visible around the vertebrae, and show the presence of an epidermal layer over the scutes.[11] The authors concluded that the osteoderms of all basal armoured dinosaurs were covered in a tough, probably keratinous layer of skin.[11]

Additional species

Scelidosaurus harrisonii, named and described by Owen, is currently the only recognized species, based on several nearly complete skeletons. A potential second species from the Sinemurian-age Lower Lufeng Formation, Scelidosaurus oehleri, was described by David Jay Simmons in 1965 under its own genus, Tatisaurus. In 1996 Spencer G. Lucas moved it to Scelidosaurus.[29] Although the fossils are fragmentary, this reassessment has not been accepted, and S. oehleri is today once again recognized as Tatisaurus.[6][30]

In 1989, scutes which were found in the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group) of northern Arizona, were by Kevin Padian referred to a Scelidosaurus sp., and used to determine that the age of the strata was around 199.6-196.5 million years ago, at a time when it was still thought that Scelidosaurus harrisonii dated to the early Sinemurian.[31] These scutes established a geographic tie-in between Arizona's Glen Canyon and Europe, where fossils of Scelidosaurus had previously been discovered.[31] Later scientists have rejected the assignment to Scelidosaurus, as the scutes are different in form.[6][24] In 2014, Roman Ulansky named a new species, S. arizonenesis, based on these specimens.[32] In 2016, Peter Malcolm Galton and Kenneth Carpenter identified it as a nomen dubium, instead once again placing the specimens as Thyreophora indet.[33]

Classification and phylogeny

Scelidosaurus was placed in the Dinosauria by Owen in 1861. In 1868/1869 Edward Drinker Cope proposed a family Scelidosauridae in a double lecture but this was only published in December 1871;[34] therefore it was Thomas Henry Huxley who validly named the Scelidosauridae in 1869.[14][35] In the nineteenth century almost any armoured dinosaur then known has been considered a member of the Scelidosauridae. In the later twentieth century, the term was used for an assembly of "primitive" ornithischians close to the ancestry of ankylosaurs and stegosaurs, such as Scutellosaurus, Emausaurus, Lusitanosaurus and Tatisaurus.[4] Today, paleontologists usually consider the Scelidosauridae paraphyletic, thus not forming a separate branch or clade; however, Benton (2004) lists the group as monophyletic.[36] The family was resurrected by Chinese paleontologist Dong Zhiming in his 2001 description of Bienosaurus, a thyreophoran sharing close affinities with Scelidosaurus.[37]

Scelidosaurus was an ornithischian. It was the oldest ornithischian known until the description of Geranosaurus in 1911.[6] During the twentieth century, it has been classified at different times as an ankylosaur or stegosaur. Alfred von Zittel (1902), William Elgin Swinton (1934), and Robert Appleby et al. (1967) identified the genus as a stegosaurian,[38] though this concept then encompassed all armoured forms. In a 1968 paper, Romer argued it was an ankylosaur.[38] In 1977, Richard Thulborn of the University of Queensland attempted to reclassify Scelidosaurus as an ornithopod similar to Tenontosaurus or Iguanodon.[38] Thulborn argued Scelidosaurus was a lightly built bipedal dinosaur adapted for running. Thulborn's 1977 theories on the genus have since been rejected.

This debate is still ongoing; at this time, Scelidosaurus is considered to be either more closely related to ankylosaurids than to stegosaurids and, by extension, a true ankylosaur,[10][39] or basal to the ankylosaur-stegosaur split.[6] The stegosaur classification has fallen out of favor, but is seen in older dinosaur books.[40] Cladistic analyses have invariably recovered a basal position for Scelidosaurus, outside of the Eurypoda.[24]

The position of Scelidosaurus according to a cladistic study of 2011 is shown by this cladogram:[41]

| Thyreophora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 2022 monograph on Scelidosaurus by David Norman, a different relationship amongst thyreophorans was found, with Stegosauria being the most basal group, and Scelidosaurus being most closely related to Ankylosauria.[42]

| Thyreophora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fossil records of thyreophorans more basal than Scelidosaurus are sparse. The more "primitive" Scutellosaurus, also found in Arizona, was an earlier genus which was facultatively bipedal. A trackway of a possible early armoured dinosaur, from around 195 million years ago, has been found in France.[43] Ancestors of these basal thyreophorans evolved from early ornithischians similar to Lesothosaurus during the Late Triassic.[6]

Paleobiology

Diet

Like most other thyreophorans, Scelidosaurus is known to be herbivorous. However, while some later ornithischian groups possessed teeth capable of grinding plant material, Scelidosaurus had smaller, less complex leaf-shaped teeth suitable for cropping vegetation and jaws capable of only vertical movement, due to a short jaw joint.[4] Paul Barrett concluded that Scelidosaurus fed with a puncture-crush system of tooth-on-tooth action, with a precise but simple up-and-down jaw movement, in which the food was mashed between the inner side of the upper teeth and the outer side of the lower teeth, without the teeth actually touching each other as shown by very long vertical wear facets on the lower teeth alone.[44] In this aspect, it resembled the stegosaurids, which also bore primitive teeth and simple jaws.[45] Its diet would have consisted of ferns or conifers, as grasses did not evolve until late into the Cretaceous Period, after Scelidosaurus was long extinct.

Another similarity with the stegosaurs is the narrow head, which might indicate a selective diet consisting of high-quality fodder. However, Barrett pointed out that for an animal the size of Scelidosaurus, with a large gut allowing efficient fermentation, the intake of easily digestible food of high energetic value was less important than with smaller animals, that are often critically dependent on it.[44] Norman concluded that Scelidosaurus fed on low scrubby vegetation, with a height up to one metre. Raising itself on its hindlimbs alone, could have vertically increased the feeding envelope and was perhaps anatomically possible, but Norman doubted it was a relevant part of its behaviour.[6]

See also

References

- Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-910207-4

- Norman, David (2001). "Scelidosaurus, the earliest complete dinosaur" in The Armored Dinosaurs, pp 3-24. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- The same claim has been made for Compsognathus

- Lambert D (1993). The Ultimate Dinosaur Book. Dorling Kindersley, New York, 110-113. ISBN 1-56458-304-X

- Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 217

- Norman, D.B., Witmer, L.M., and Weishampel, D.B. (2004). "Basal Thyreophora". In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (ed.). The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. University of Californian Press. pp. 335–342. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gierliński, Gregard (1999). "Tracks of a large thyreophoran from the Early Jurassic of Poland" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 44. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Norman, David B. (2020). "Scelidosaurus harrisonii from the Early Jurassic of Dorset, England: cranial anatomy". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 188 (1): 1–81. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz074.

- Maidment, S.C.R., Porro, L.B., 2010, "Homology of the palpebral and origin of the supraorbital ossifications in ornithischian dinosaurs", Lethaia, 43: 95-111

- Kazlev, M. Alan (2007). "Ornithischia: Ankylosauromorpha" Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine Palaeos. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

- Martill, D.M., Batten, D.J., and Loydell, D.K. (2000). A New Specimen of the Thyreophoran Dinosaur cf. Scelidosaurus with Soft Tissue Preservation. Palaeontology, Vol. 43, Part 3, 2000, pp. 549-559. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2000.00139.x

- Naish, D. & Martill, D.M., 2007, "Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia", Journal of the Geological Society, London, 164: 493–510

- Owen, R., 1859, "Palaeontology", In: Encyclopædia Britannica Edition 8, Volume 17, p. 150

- Charig, A.J. & Newman, B.H.†, 1992, "Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen, 1861 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): proposed replacement in inappropriate lectotype", Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 49: 280–283

- R. Owen, 1861, A monograph of a fossil dinosaur (Scelidosaurus harrisonii, Owen) of the Lower Lias, part I. Monographs on the British fossil Reptilia from the Oolitic Formations 1 pp 14

- George C. Steyskal, 1970, "On the grammar of names formed with -scelus, -sceles, -scelis, etc.", Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 84(2): 7-12

- R. Owen, 1863, A monograph of the fossil Reptilia of the Liassic Formations. Part 2. A monograph of a fossil dinosaur (Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen) of the Lower Lias. Palaeontographical Society Monographs. Part 2. pp. 1-26

- Norman, D.B., 2000, "Professor Richard Owen and the important but neglected dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisonii", Historical Biology, 14: 235–253

- Lydekker, R., 1888, Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum. Part 1. Containing the Orders Ornithosauria, Crocodilia, Dinosauria, Squamata, Rhynchocephalia and Proterosauria. British Museum (Natural History)

- Newman, B.H. (1968) The Jurassic dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisoni, Owen. Palaeontology 11 (1), 40-3.

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, 1994, "Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen, 1861 (Reptilia, Ornithischia): lectotype replaced", Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 51: 288

- Pickering, S., 1995, Jurassic Park: Unauthorized Jewish Fractals in Philopatry. A Fractal Scaling in Dinosaurology Project, 2nd revised printing. Capitola, California. 478 pp

- Benson, R., 2010, "The osteology of Magnosaurus nethercombensis (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of the United Kingdom and a re-examination of the oldest records of tetanurans", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 8(1): 131-146

- Barrett, P.M. and Maidment, S.C.R., 2011, "Dinosaurs of Dorset: Part III, the ornithischian dinosaurs (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) with additional comments on the sauropods", Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 132: 145–163

- Rixon, A.E., 1968, "The development of the remains of a small Scelidosaurus from a Lias nodule", Museums Journal, 67: 315–321

- Delair, J.B., 1959, "The Mesozoic reptiles of Dorset: Part Two", Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, for 1958 80: 52-90

- Ensom, P.C., 1989, "New scelidosaur remains from the Lower Lias of Dorset", Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 110: 165 & 167

- Simms, Michael J.; Smyth, Robert S.H.; Martiall, David M.; Collins, Patrick C.; Byrne, Roger (2021). "First dinosaur remains from Ireland". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 132 (6): 771–779. Bibcode:2021PrGA..132..771S. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2020.06.005. S2CID 228811170.

- Lucas SG. (1996). The Thyreophoran Dinosaur Scelidosaurus from the Lower Jurassic Lufeng Formation, Yunnan, China. pp. 81-85, in Morales, M. (ed.), The Continental Jurassic. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 60.

- Norman, David B.; Butler, Richard J.; Maidment, Susannah C.R. (2007). "Reconsidering the status and affinities of the ornithischian dinosaur Tatisaurus oehleri Simmons, 1965" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 150 (4): 865–874. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00301.x.

- Padian, K. (1989). "Presence of the dinosaur Scelidosaurus indicates Jurassic age for the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group, northern Arizona)". Geology. May 1989, v. 17; no. 5; p. 438-441

- Ulansky, R. E., 2014. Evolution of the stegosaurs (Dinosauria; Ornithischia). Dinologia, 35 pp. [in Russian]. [DOWNLOAD PDF] http://dinoweb.narod.ru/Ulansky_2014_Stegosaurs_evolution.pdf.

- Galton, Peter M. & Carpenter, Kenneth, 2016, "The plated dinosaur Stegosaurus longispinus Gilmore, 1914 (Dinosauria: Ornithischia; Upper Jurassic, western USA), type species of Alcovasaurus n. gen.", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 279(2): 185-208

- E.D. Cope, 1871, Synopsis of the extinct Batrachia, Reptilia and Aves of North America. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series 14, pp 252

- Huxley, T.H. 1869. "On the Dinosauria of the Trias, with observations on the classification of the Dinosauria", Nature, 1: 146

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology (Third ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8

- Dong Zhiming (2001). "Primitive Armored Dinosaur from the Lufeng Basin, China". In Tanke, Darren H.; Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 237–243. ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- Thulborn, R.A. (1977) Relationships of the lower Jurassic dinosaur Scelidosaurus harrisonii. Journal of Paleontology. July 1977; v. 51; no. 4; p. 725-739

- Carpenter, Kenneth (2001). "Phylogenetic Analysis of Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 455–480. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- Colbert, Edwin H. (1965). The Age of Reptiles. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-486-29377-6.

- Richard S. Thompson, Jolyon C. Parish, Susannah C. R. Maidment and Paul M. Barrett, 2011, "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2): 301–312

- Norman, David B (1 January 2021). "Scelidosaurus harrisonii (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Early Jurassic of Dorset, England: biology and phylogenetic relationships". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191 (1): 1–86. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa061. ISSN 0024-4082.

- Le Loeuff, J., Lockley, M., Meyer, C., and Petit, J.-P. (1999). Discovery of a thyreophoran trackway in the Hettangian of central France. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 2 328, 215-219

- Barrett, P.M. (2001). "Tooth wear and possible jaw action of Scelidosaurus harrisoni Owen and a review of feeding mechanisms in other thyreophoran dinosaurs". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 25–52. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- Galton PM; Upchurch P (2004). "Stegosauria". In Weishampel DB; Dodson P; Osmólska H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

External links

- Ankylosauromorpha at the Tree of Life

- Scelidosauridae