Nicolo Schiro

Nicolo "Cola" Schiro (born Nicolò Schirò;[lower-alpha 1] Italian pronunciation: [nikoˈlɔ skiˈrɔ]; September 2, 1872 – April 29, 1957) was an early Sicilian-born New York City mobster who, in 1912, became the boss of what later become known as the Bonanno crime family.

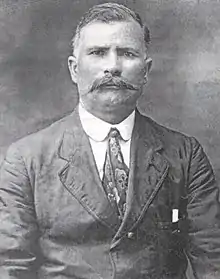

Nicolo Schiro | |

|---|---|

Schiro, 1923 | |

| Born | Nicolò Schirò September 2, 1872 |

| Died | April 29, 1957 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | Italian, American (revoked) |

| Other names | "Cola", Nicola Schiro |

| Occupation(s) | Crime boss, mobster, yeast dealer |

| Predecessor | Sebastiano DiGaetano |

| Successor | Salvatore Maranzano |

| Allegiance | Schiro crime family |

| Signature | |

Schiro's leadership of the mafia clan would see it orchestrate the "Good Killers" murders, control gambling and protection rackets in Brooklyn, engage in bootlegging during Prohibition, and print counterfeit money.

A conflict with rival mafia boss Joe Masseria would force Schiro out as boss, after which he returned to Sicily.

Early life

Nicolò Schirò was born on September 2, 1872, in the town of Roccamena, in the Province of Palermo, Sicily to Matteo Schirò and his wife, Maria Antonia Rizzuto.[2] His father's family came from the Arbëreshë community of Contessa Entellina. A few years later, Schiro's family moved to his mother's hometown in nearby Camporeale.[2]

Schiro immigrated to the United States in 1897.[2] By May 1902, he was living in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, following a return trip to Sicily.[3]

In April 1905, Schiro was arrested for operating a butcher shop on a Sunday contrary to New York's Blue laws.[4] He would later become a yeast salesman and broker.[5][6]

Mafia boss

Schiro became the new head of the local mafia centered in Williamsburg in March 1912, replacing Sebastiano DiGaetano.[7]

Secret Service informant Salvatore Clemente reported in November 1913 that Schiro was aligned with the Morello crime family in a war against fellow New York mafia boss, and capo dei capi, Salvatore D'Aquila.[8] Schiro later developed a more neutral stance, siding with neither D'Aquila's nor the Morello mafia clans.[9]

Schiro's gang ran the Williamsburg area numbers gambling racket while extorting local Italian immigrants through Black Hand and protection rackets. If their extortion money was not paid, the victims' homes or businesses could be vandalized or destroyed.[10]

Schiro ran his mafia clan conservatively, conducting its criminal activity primarily among Sicilian immigrants and not collaborating with non-Sicilian gangs. He was never arrested during his time as boss, avoiding attention from authorities and the media.[11]

Schiro developed close relationships with local business and political leaders;[12] and was on the board of directors of the local United Italian-American Democratic Club.[13]

Schiro's first application for United States citizenship was rejected in 1913 due to his "lack of knowledge of the US Constitution". He later successfully naturalized as an American citizen in 1914.[14][15]

In 1919, the Bureau of Investigation reviewed a list of Black Hand suspects in southern Colorado compiled by the sheriff of Huerfano County. On the list of names was Schiro gangster Frank Lanza, with the sheriff writing that Lanza had arrived in Colorado from New York "every May pretending to buy cheese but comes to organize Black-handers".[16]

"The Good Killers"

Left to right, front row: Stefano Magaddino, Francisco Puma, Vito Bonventre and Bartolo Fontana. Center, rear: Giuseppe Lombardi.

On November 11, 1917, two Schiro gangsters, Antonio Mazzara and Antonino DiBenedetto were shot to death near the intersection of North 5th and Roebling streets in Brooklyn. One gunman, Antonio Massino, was arrested near the scene but another, Detroit mobster Giuseppe Buccellato, escaped. Buccellato killed Mazzara and DiBenedetto after they refused to divulge the whereabouts of fellow Schiro gangster, Stefano Magaddino. Magaddino had orchestrated the murder earlier that March of Giuseppe's brother and fellow Detroit gangster, Felice Buccellato due to the mafia clan of Magaddino and Vito Bonventre feuding with the mafia clan of the Buccellatos back in their hometown of Castellammare del Golfo.[17][18]

1917 Detroit autoworker shootings

Determined to kill but unable to locate Giuseppe Buccellato, Schiro and Magaddino decided to target his family. Giuseppe's cousin, Pietro Buccellato, worked at the Ford Motor Company factory in Highland Park, Michigan and Schiro arranged with Detroit mafia boss Tony Giannola to have him murdered.[19]

On December 8, 1917, a Romanian autoworker named Joseph Constantin, who was mistaken for Pietro Buccellato, was shot and wounded.[20]

On December 19, another Romanian autoworker in Detroit was mistaken for Pietro Buccellato. Paul Mutruc was shot several times in the back and then shot twice in the head, killing him.[21][22]

On December 22, as Pietro Buccellato waited with other passengers to board an approaching trolley, two gunmen fired multiple shots into Buccellato. An errant shot through one of the trolley windows nearly hit a passenger. Buccellato survived long enough to be taken to a hospital where he told police, before dying, he was attacked "on account of his cousin".[23][24]

Murder of Camillo Caiozzo

A barber named Bartolo Fontana turned himself into the New York police in August 1921, confessing to murdering Camillo Caiozzo a couple of weeks earlier in New Jersey. Salvatore Cieravo, a New Jersey innkeeper who helped Fontana dispose of Caiozzo's body had just been arrested. Fontana claimed he murdered Caiozzo at the behest of the "Good Killers", a group of leading mafiosi in the Schiro gang who hailed from Castellammare del Golfo, in retaliation for Caiozzo's involvement in the 1916 murder of Stefano Magaddino's brother, Pietro Magaddino, back in Sicily. Fontana fearing he might be murdered by Schiro's gang, agreed to help police set up a sting operation. Stefano Magaddino met Fontana at Grand Central Station to give Fontana $30[lower-alpha 2] to help him flee the city. After the exchange, Magaddino was arrested by a group of undercover police. Vito Bonventre, Francesco Puma, Giuseppe Lombardi and two other gangsters were subsequently arrested for their involvement in the murder.[26][27]

Fontana revealed that the "Good Killers" were also responsible for a string of other murders.[26] Some of the victims were connected to the Buccellato mafia clan in Castellammere del Golfo,[28] while others had complained after being cheated in gambling rackets run by the Schiro gang.[27] Also targeted were supporters of Salvatore Loiacano, who had taken over the Morello gang with Salvatore D'Aquila's backing. Loiacano was murdered on December 10, 1920, several months after Giuseppe Morello had been released from prison. According to a March 1, 1921 article in the New York Evening World, seven men had placed their hands on Loiacano's corpse during his funeral and vowed revenge. Within a few months, three of the vow makers – Salvatore Mauro, Angelo Patricola, and Giuseppe Granatelli were murdered and a fourth, Angelo Lagattuta was shot and severely wounded. Fontana named them all as victims of the "Good Killers". Morello had made a deal with Schiro, his earlier ally against D'Aquila, to kill Loiacano's supporters with people unfamiliar to them.[29][30]

New Jersey decided not to pursue conspiracy charges in the Caiozzo murder. Charges against Magaddino were dropped despite the New York police officers' testimony about the sting linking him to the murder, as well as the charges against Bonventre. Only the charges against Fontana and the three men who helped dispose of the body - Puma, Lombardi, and Cieravo - remained. Francesco Puma was murdered on a New York street while out on bail awaiting trial, with a stray bullet from the shooting also hitting a seven-year-old girl.[31] Fontana went to prison for Caiozzo's murder while the charges against Cieravo and Lombardi were eventually dropped.[26] Magaddino fled New York City after his release, ending up in the Buffalo, New York area.[32]

1920s and Prohibition

Several Schiro gangsters became mafia bosses in other cities – Frank Lanza in San Francisco, Stefano Magaddino in Buffalo, and Gaspare Messina in New England.[33] Schiro was also close to future Los Angeles boss, Nick Licata.[34]

In April 1921, Schiro admitted Nicola Gentile into his gang in order to protect Gentile from capo dei capi Salvatore D'Aquila as a show of Schiro's independence from D'Aquila.[35][36]

Schiro gangster, Giovanni Battista Dibella[lower-alpha 3] was arrested (under the alias Piazza) on July 14, 1921, when over $100,000[lower-alpha 4] worth of whiskey and numerous forged medicinal liquor permits were seized during a raid by Prohibition agents Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith at Dibella's olive oil warehouse in Brooklyn.[39][40] Schiro had been a witness at Dibella's wedding in 1912.[41]

Counterfeit money

On August 2, 1922, Secret Service agents arrested Schiro gangster Benjamin Gallo, along with four others, for operating a sophisticated counterfeiting plant at a bakery on Rockaway Avenue in Brooklyn. There agents found dyes, presses, paper, and hundreds of dollars worth of counterfeit $5, $10, and $20 bills; along with an illicit alcohol still.[42][43]

Bootlegging and immigration fraud

Future boss Joseph Bonanno illegally immigrated to the U.S. during the mid-1920s,[44] soon joining the Schiro gang as a protege of Salvatore Maranzano.[45] In his autobiography, Bonanno writes he thought Schiro was "a compliant fellow with little backbone" and "extremely reluctant to ruffle anyone".[46] Bonanno's second cousin, Vito Bonventre, remained a leader within Schiro's gang following his arrest and release during the "Good Killers" affair. During Prohibition, Bonventre developed a widespread bootlegging operation with Bonanno recalling "Next to Schiro, Bonventre was probably the most wealthy" of the gang.[47]

Maranzano, a Castellammare del Golfo-born son-in-law of a Sicilian mafia boss in Trapani, had joined the Schiro mafia clan in the mid-1920s and helped it create an extensive bootlegging network in Dutchess County, New York, along with a ring providing fraudulent immigration and naturalization documents to Italians smuggled into the United States.[48][49]

Ouster and return to Sicily

Between 1923 and 1928, Schiro felt secure enough in his position as boss to make three trips to Europe.[50]

Salvatore D'Aquila was murdered on October 10, 1928.[51] Fellow New York boss Joe Masseria was selected to replace D'Aquila as the new capo dei capi.[52] Following his elevation, Masseria began demanding monetary tributes from other mafia clans.[53]

In January 1929, Schiro traveled to Los Angeles to attend the wedding of the son of San Francisco boss Frank Lanza.[54]

Schiro provoked Masseria's ire after warning Lanza of a mafia plot to kidnap him.[34]

Masseria demanded Schiro pay $10,000[lower-alpha 5] and step down as boss of his mafia crime family in order to spare his life.[55][56]

After being forced out, Schiro returned to his hometown of Camporeale, Sicily.

Judicial summons for Schiro and other officers of the Masterbilt Housing Corporation were published in Brooklyn newspapers in the fall of 1931.[57]

In 1934, a memorial was dedicated in Camporeale to its soldiers killed during World War I. It was built from donations collected by Schiro from Camporealese immigrants in America.[58][59]

Schiro was stripped of his U.S. citizenship following a request by the American consulate in Palermo on October 14, 1949.[60] He died in Camporeale on April 29, 1957.[34]

Notes

- His first name is also sometimes written as Nicola.[1]

- Approximately $470 in 2021 U.S. dollars.[25]

- Giovanni Battista Dibella and Salvatore Dibella were brothers of John Dibella (Giovanni Vincenzo Dibella), a business partner and crony of Schiro successor Joseph Bonanno.[37][38]

- Approximately $1.6 million in 2021 U.S. dollars.[25]

- Approximately $163,000 in 2021 U.S. dollars.[25]

References

Citations

- Dash 2010, p. 320.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 55.

- Critchley 2009, p. 214.

- "FALVEY AFTER BUTCHERS. Selling on Sunday Not Permitted in the Lee Avenue Precinct". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1 May 1905. p. 20. Retrieved 11 March 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hunt 2020, pp. 123–4.

- Petepiece 2021, pp. 2–4, 7.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 54–55.

- Dash 2010, p. 324.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 59–61.

- Petepiece 2021, p. 10.

- Critchley 2009, p. 137.

- Waugh 2019, p. 400 n198.

- "Italian-American Democrats' Election". The Brooklyn Standard Union. 14 December 1916. p. 8.

- Critchley 2009, p. 311 n127.

- Petepiece 2021, pp. 2–3.

- O'Haire 2021, p. 66.

- Waugh 2019, pp. 194–195.

- "TWO DIE IN STREET AFTER SEVEN SHOTS; Detective Pursues Two Men With Pistols and Makes One a Prisoner". New York Herald. 12 November 1917.

- Waugh 2019, p. 196.

- Waugh 2019, p. 198.

- Waugh 2019, pp. 198–199.

- "RUMANIAN SHOT TO DEATH". Detroit Times. 19 December 1917. p. 1.

- Waugh 2019, pp. 199–201.

- "MAN SHOT OFF STREET CAR STEPS: Third Victim in "Homicide Belt" Dies From Wound". Detroit Times. 22 December 1917. p. 1.

- "CPI Inflation Calculator". www.bls.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Hunt, Thomas; Tona, Michael A. (Spring 2007). "The Good Killers 1921's Glimpse of the Mafia". On the Spot Journal of Crime and Law Enforcement History. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019 – via The American Mafia.

- "SIXTEEN MURDERS BY DEATH BAND HERE REVEALED; Member of Gang, Himself Slated to Die, Discloses Operations - 7 Under Arrest". Brooklyn Daily Times. 17 August 1921. pp. 1–2.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 216–229.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 64.

- "5th MAN DONE FOR OUT OF EIGHT IN DEADLY VENDETTA; First Victim Picked Off on Dec. 10 Last - Seven Swore to Avenge Him; SECOND 'GOT' ON DEC. 29; Next on Jan. 23, and So On - Now the Three Await, Still Vengeful". The Evening World. 1 March 1921. p. 1.

- "CONVICT KILLED, GIRL SHOT, FROM ASSASSIN AUTO". New York Daily News. 5 November 1922.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 216–222.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 55–56.

- Hunt 2020, p. 124.

- Petepiece 2021, pp. 4–5.

- Hunt et al. 2020, pp. 12–13.

- Schmitt 2012, p. 58.

- Gores, Stan (12 March 1966). "Dibella Lived At Hotel, Headed Grande Cheese Firm; Meetings With Bonanno Kept Him In Spotlight". Fond du Lac Commonwealth Reporter. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- Schmitt 2012, pp. 58–59.

- "FEDERAL DRY SQUAD MAKES BIG HAUL; Whiskey Valued at $100,000 and Fake Permits Seized in Boerum Street Raild; 500 BARRELS IN TRANSIT; Proprietor of Oil Concern Faces Conspiracy Charge". The Brooklyn Standard Union. 15 July 1921. p. 3.

- Schmitt 2012, p. 59.

- Downey 2004, p. 158.

- "RAIDERS NAB 5 SUSPECTED OF COUNTERFEITING". Brooklyn Citizen. 3 August 1922. p. 3.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 55–61.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 70–71, 76–80.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, p. 93.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 78, 102–103.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 144–147.

- Lupo 2015, p. 57.

- Petepiece 2021, pp. 7–8.

- Critchley 2009, p. 157.

- Hortis 2014, p. 74.

- Hortis 2014, pp. 80–81.

- Petepiece 2021, p. 9.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 165–191.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, p. 102.

- Petepiece 2021, p. 11.

- Accardo, Luigi (1995). Camporeale: Origini, Usi, Costumi, Mentalita, Proverbi, Canti popolari (in Italian). Alcamo, Sicily: Edizioni Campo. pp. 54–55.

- "Museo/Monumento" (in Italian). Comune di Camporeale.

- Critchley 2009, p. 311n127.

Sources

- Bonanno, Joseph; Lalli, Sergio (1983). A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780312979232.

- Buccellato, James A. (2015). Early Organized Crime in Detroit: Vice, Corruption and the Rise of the Mafia. Charleston: The History Press. ISBN 9781625855497.

- Critchley, David (2009). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415990301.

- Dash, Mike (2010). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder and the Birth of the American Mafia. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345523570.

- Downey, Patrick (2004). Gangster City: A History of the New York Underworld, 1900-1935. Barricade Books. ISBN 9781569802670.

- Ghiglieri, Matt; O'Haire, Michael (October 2023). "Lanza's NY firms may have been Mafia fronts: San Francisco's boss made his early fortune on Manhattan's Lower East Side". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 102–109.

- Hortis, C. Alexander (2014). The Mob and the City: The Hidden History of how the Mafia Captured New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781616149239.

- Hunt, Thomas; Critchley, David; Van't Reit, Lennert; Turner, Steve (October 2020). "Nicola Gentile: Chronicler of Mafia History". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 5–41.

- Hunt, Thomas (October 2020). "The others: Bios of significant figures in Gentile's life story". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 87–144.

- Lupo, Salvatore (2015). The Two Mafias: A Transatlantic History, 1888-2008. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9781137491374.

- O'Haire, Michael (October 2021). "San Francisco boss Lanza held key role with Colorado's Mafia". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 66–68.

- Petepiece, Andy (2021). The Bonanno Family: A History of New York's Bonanno Mafia Family. Tellwell. ISBN 9780228852919.

- Schmitt, Gavin (July 2012). "The Underworld's Interest in Wisconsin's Cheese". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 56–65.

- Warner, Richard; Santino, Angelo; Van't Reit, Lennert (May 2014). "Early New York Mafia: An Alternative Theory". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement.

- Waugh, Daniel (2019). Vinnitta: The Birth of the Detroit Mafia. Lulu Publishing Services. ISBN 9781483496276.

External links

- Struggle for Control - The Gangs of New York, article by Jon Black at GangRule.com.

- Detroit fish market murders spark Mafia war, article by Thomas Hunt at The Writers of Wrongs.

- Two killed at Castellammarese colony in Brooklyn, article by Thomas Hunt at The Writers of Wrongs.

- New York Mob Leaders - Bonanno at The American Mafia.

- Nicolo Schiro information in the FBI file of James Lanza, at Internet Archive.