Schräge Musik

Schräge Musik, which may also be spelled Schraege Musik, was a common name for the fitting of an upward-firing autocannon or machine gun, to an interceptor aircraft, such as a night fighter. The term was introduced by the German Luftwaffe during World War II. "Schräge Musik" was previously a German colloquialism, meaning music that featured an unusual tuning and/or time signature (e.g., Jazz). The standard usage of the adjective schräg is often translated as "slanting" or "oblique", but its slang usage is often translated as "weird" or "strange".

The first such systems were developed (though not widely employed) in World War I as anti-Zeppelin defenses by the French and British, in an era when fighters struggled to match the altitude capacity of the German airships and were forced to devise means to attack from below. The later resurrection of the concept by the Germans was inspired by observed weaknesses in the standard British night bomber aircraft of the WW2 era (the Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax), which lacked ventral ball turrets in order to save weight, making them vulnerable to covert approaches and attacks from below under the cover of darkness. In keeping with the plans of the Allied Combined Bomber Offensive, the American B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberators operating in Europe (factory-equipped with ball turrets) typically bombed at lower altitudes and by day, thus experiencing far fewer encounters (and relative losses) from Schräge Musik. Later similar Japanese experiments with upward-firing cannons on their night fighters in 1944 (intended to target the American B-29 Superfortress fleet firebombing Japan by night) were largely fruitless, owing to the B-29's notably superior speed and altitude.

In the initial stages of its operational use by German air crews, from mid-1943 to early 1944, many attacks using Schräge Musik achieved complete surprise while destroying many British bombers. The crews that survived such attacks, during this period, often believed that damage and casualties had been caused by ground-based anti-aircraft artillery (AA or AAA),[1] rather than fighters, and much confusion resulted until the cause was successfully pinpointed.

Background

World War I

_(14597183720).jpg.webp)

During World War I, pusher-configured fighter aircraft with flexibly-mounted forward-firing machine guns (especially the Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2s), enabled gunners to discover the principle of zero-deflection shooting. When firing upward at roughly a 45° elevation, when the attacking aircraft and its target are travelling at about the same speed and the range is fairly short, the trajectory will appear straight. The bullets' true path is a parabola, but the movement forward of both aircraft, and the air passing the aircraft counter the tendency of the round to arc down after leaving the muzzle so it appears to follow a straight line, simplifying accurate sighting which then requires no deflection or leading of the target.

The pilots of Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 night fighters, after trying various schemes for attacking the Zeppelin raiders of 1915–16, hit on the idea of firing a mixture of explosive and incendiary bullets into the body of the airship from below. For this purpose a .303 in (7.7 mm) air-cooled Lewis gun was mounted in front of the pilot, firing upward. Exploitation of this led to the destruction of six German airships between September and December 1916. Later British night fighters were similarly armed with upward firing guns.

Several tractor-configured single-seat biplanes of the time featured machine guns mounted on the centre section of the top wing to fire over the radius of the propeller to bypass the need for synchronization gears). Both the French mountings and the British Foster mounting allowed a machine gun to be tipped back to reload and whether by accident or design, this allowed the gun to be held at an intermediate angle (ideally about 45°) and fired upward, steadying the gun and firing it with the "normal" trigger rather than the remote Bowden cable used for forward firing. These could then be used to attack enemy aircraft from the blind spot below the tail. Most notable of the airplanes used were the Nieuport 11, 16 and 17 and 23 fighters from 1915 onwards, and the tactic was continued in British service, with the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5s and Sopwith Dolphin. That Dolphin entered service near the end of World War I, and was delivered with a pair of .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis guns on a cross-tube connecting the upper wing spars. British ace Albert Ball in particular was a great exponent of this technique,[2] The Germans copied the arrangement in 1917, when Gerhard Fieseler of Jasta 38 attached two machine guns to an Albatros D.V, pointing upwards and forwards.

Interwar years

The Boulton Paul Bittern was a twin-engined night fighter (designed to Specification 27/24) with an armament of barbette mounted guns, that could be angled upwards for attack against bombers, without having to enter a climb. The first of two Bittern prototypes flew in 1927, though performance was poor and the development stopped.

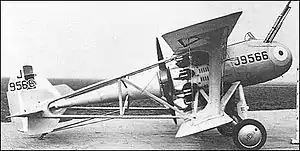

The Westland C.O.W. Gun Fighter (1930) and Vickers Type 161 (1931) were designed in response to Air Ministry specification F.29/27. This called for an interceptor fighter operating as a stable gun platform for the Coventry Ordnance Works 37 mm autocannon produced by the Coventry Ordnance Works (COW).

The COW gun had been developed in 1918 for use in aircraft and had been tested on the Airco DH.4. The cannon fired 23-ounce (0.65 kg) shells and was to be mounted at 45 deg or more above the horizontal. The tactic was to fly below the target bomber or airship and fire upwards into it. Gun firing trials with both types went well, with no detriment to airframe or performance, although the Westland prototype displayed "alarming" handling characteristics. Neither the Type 161 nor its competitor, the Westland C.O.W. Gun Fighter were ordered, and no more was heard of this use of the aerial COW gun.[3][4][N 1]

Similar logic lay behind the later Vickers Type 414 twin-engined fighter. This aircraft, which can be seen a natural successor to the Vickers COW gun fighter, combined a streamlined monoplane two-seater fighter airframe with a remotely controlled nose-mounted 40mm cannon that could be elevated for no-allowance shooting.[5]

While turret fighters like the Boulton Paul Defiant and the naval Blackburn Roc addressed the same threat – enemy bombers attacking the UK – the approach was very different: upward-firing guns and no-allowance shooting are separate and distinct, and the equipment that can do the one can, generally speaking, be arranged so as to do the other (unless the fixed armament is automatically triggered, as in the photo-cell firing arrangements detailed below). On paper at least, the advantages of flexible aim and weight of fire from a two-seater were clear: the pilot is not overburdened, several fighters could be brought to bear on a target together, and there are two pairs of eyes per aircraft. However, the weight of a powered turret and air gunner imposed performance penalties.

The RAF put the Defiant into service in 1939, intending to use it against bombers, despite the bombers' numerous gun positions. However, the unexpected German territorial gains in France meant that bombers were escorted by fighters. Despite being utterly outclassed as a day fighter, when moved to the night-fighter role it had some success, typically attacking from below and slightly ahead of the bomber, well outside its field of defensive fire.[6]

Meanwhile, in the United States, the twin-engine Bell YFM-1 Airacuda was designed as a "bomber-destroyer", touted as "... a mobile anti-aircraft platform."[7] Its armament included mainly forward-firing M4 37mm cannon, with an accompanying gunner mounted in a forward compartment of each of the two engine nacelles. Theoretically, the cannon could be slewed, aimed and fired at an oblique angle but flight tests and operational evaluation, disproved the theory: the type proved troublesome and except for initial flight testing in 1937, where full armament was carried, the nacelle cannon armament and the accompanying gunner–loaders were eliminated in the final development aircraft.[8]

World War II

German developments

Oberleutnant Rudolf Schoenert of 4./NJG 2 decided to experiment with upward-firing guns in 1941 and began trying out upward-firing installations, amid scepticism from his superiors and fellow pilots.[9] The first installation was made late in 1942, in a Dornier Do 17Z-10 that was also equipped with the early UHF-band version of the FuG 202 Lichtenstein B/C radar. In July 1942, Schoenert discussed the results of his experiment with General Kammhuber, who authorized the conversion of three Dornier Do 217J-1s, to add a vertical armament of four or six MG 151s. Further experiments were carried out by the Luftwaffe flight testing centre Erprobungsstelle) at Tarnewitz on the Baltic Sea coast through 1942. An angle between 60° and 75° was found to give best results, allowing a target turning at 8°/sec to be kept in the gunsight.[9]

Schönert was made CO of II./NJG 5, and an armourer serving with the Gruppe, Oberfeldwebel Mahle, developed a working arrangement with the unit's Messerschmitt Bf 110s, mounting a pair of MG FF/M 20 mm (0.79 in) cannon in the rear compartment of the upper fuselage, firing through twin holes in the canopy's glazing. Schönert used such a modified Bf 110 to shoot down a bomber in May 1943. From June 1943, an official conversion kit was produced for the Junkers Ju 88 and Dornier Do 217N fighters.[9] Between August 1943 and the end of the year, Schönert achieved 18 kills with the new gun installation.[10]

Before the introduction of Schräge Musik in 1943, the Nachtjagdgeschwadern (NJG, night fighter wings) were simply equipped with heavy fighters fitted with radar in the nose and a combination of front-firing and defensive weapons.

In the standard interception, the fighter approached the target from the rear to get into a firing position, presenting the night fighter crew with a much smaller target, a problem compounded by the Royal Air Force bombers (such as the Whitley and Wellington medium bombers) first being fitted with twin-gun hydraulic tail turrets, later upgraded to four guns to fend off just such attacks.

While the small .303 in (7.7 mm) calibre made these tail turret guns less effective than hoped,[11] rear-gunners also maintained a watch for fighters and, if warned, the pilot would make evasive manoeuvres such as corkscrews. Night-fighter pilots therefore developed a new tactic to avoid the turret guns: instead of approaching directly from the rear they would approach about 1,500 ft (460 m) below the bomber, pull up sharply and start firing when the nose of the bomber appeared in the gunsight. As the fighter slowed and the bomber passed over them, its wings were sprayed with cannon or machine gun rounds. While effective, this manoeuvre was difficult to perform, there was a risk of collision and, if the bomb load exploded, it could also destroy the attacking aircraft.

Systems similar to the original Schräge Musik, such as the Sondergerät 500 or Jägerfaust, were tested on day fighters and other airframes, with the largest-calibre upward-firing aerial ordnance in German service, based on the quintuple-launcher of the 21 cm Nebelwerfer infantry barrage rocket, the experimental heavy-bomber based Grosszerstörer (heavy destroyer) also under test.

The Jägerfaust system, firing 50 mm (2 in) projectiles vertically into the lower sides of bombers, was triggered by an optical device, so the pilot's only task was to pass beneath the target. This was tested on the Fw 190, and was destined for installation in the Messerschmitt Me 163B and the Me 262B. The definitive night fighter version of the Messerschmitt Me 262, the Me 262B-2, was also designed to carry such an installation but the system was a failure and it was not used operationally. Trials with the Me 163 were promising, with six operational aircraft modified. On 10 April 1945, a Halifax bomber was shot down by Fritz Kelb flying a Jägerfaust-equipped Me 163B, most probably from I. Gruppe/JG 400 operating from Brandis, Germany.[12]

As experimental aircraft were developed as night fighters, such as the Horten Ho 229, a Schräge Musik system was incorporated from the outset. The experimental Horten Ho 229 flying wing series was proposed for consideration, with a form of unusual upward-firing armament for testing on the V4 night fighter prototype, photoelectric fired vertically mounted rockets or recoilless guns, instead of cannon armament inspired by the Jagdfaust.[13]

Typical installations

- Dornier Do 217N: 4 × 20 mm MG 151/20

- Focke-Wulf Fw 189: 1 × 20 mm MG151/20 (used mainly on Eastern Front)

- Heinkel He 219: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

- Junkers Ju 88C/G: 2 × 20 mm MG 151/20

- Junkers Ju 388J: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

- Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4: 2 × 20 mm MG FF/M

- Messerschmitt Me 262B-2: 2 × 30 mm MK 108 (proposal only, B-2 version never produced)

- Focke-Wulf Ta 154: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

Method of sighting guns

In the Ju 88 G-6 night fighter, which was both fast and manoeuvrable, the Revi 16N gunsight was modified to allow the pilot to aim at the target by placing a mirror above his head, parallel to a similar mirror placed behind the gunsight (where the eye would normally be), which was further to the rear, functioning together in the manner of a periscope. The Ju 88 G-6 was guided into position from sighting and final approach by commands from the radar operator, with the pilot only taking over when visual contact was made just prior to firing.[14]

What a contrast with SCHRÄGE MUSIK! Again the technique was to approach deliberately at a lower level, but this time all the night fighter pilot had to do was slow up a little, rise up below the bomber and hold formation. An NJG expert could follow his observer's directions, acquire the bomber visually, close and destroy it within 60 seconds. The firing position, with the bomber 65° to 70° above the fighter, was an almost ideal one. The fighter could see the bomber clearly, as a darker silhouette either blotting out the stars or against paler sky or high cloud. It presented the biggest possible target and reflected any light from searchlights, ground fires or TIs [target indicators]. With the two aircraft in close formation, there was an ideal no-deflection shot. And the fighter was perfectly safe, because it was well below the Monica beam and could not be seen by any member of the bomber's crew. The only snag was that the Luftwaffe's guns were so effective that the night fighter usually had to get out of the way very fast. It was rather like 1916, except that a Lancaster with one wing blown off tumbled downwards and backwards faster than an ignited airship.[15] [N 2]

Operational use

"We had dropped our bombs on a synthetic-oil plant in Gelsenkirchen, Germany the night of June 12/13, 1944 and were headed for base. In the tail gun turret I was searching in the dark for any enemy fighters who might be following us out of the target area. Suddenly I heard cannons barking loudly and saw lights flashing directly below. What the hell was that? I didn’t see the fighter – just the flashing. We took evasive action and that was it.

Air Gunner Leonard J. Isaacson.[16]

Schräge Musik (or Schrägwaffen, as it was also called) was first used operationally during Operation Hydra (the first instance of the Allied bombing of Peenemünde) on the night of 17/18 August 1943. [N 3] Three waves of aircraft bombed the area, and a diversion on Berlin by RAF Mosquitoes attracted the main Luftwaffe fighter effort, which meant that only the last of the three waves was met by many night fighters.[17] Number 5 Group and RCAF 6 Group in the third wave lost 29 of their 166 bombers, well over the 10 percent losses considered "unsustainable". In this raid 40 aircraft were lost: 23 Lancasters, 15 Halifaxes and two Short Stirlings.

Adoption of Schräge Musik began in late 1943 and by 1944, a third of all German night fighters carried upward-firing guns. Schräge Musik proved most successful in the Jumo 213 powered Ju 88 G-6. An increasing number of these installations used the more powerful 30-millimetre (1.2 in) calibre, short-barrelled MK 108 cannon, such as those fitted to the Heinkel He 219, fully contained within the fuselage.[18] By mid-1944, He 219 aircrew were critical of the MK 108 installation, because its low muzzle velocity and limited range, meant that the night fighter had to be close to the bomber to attack and be vulnerable to damage from debris. They demanded that either the MK 108s be removed and replaced by MG FF/Ms or the angle of the mounting be changed. Although He 219s continued to be delivered with the twin 30 mm mounted, these were removed by front line units.[19] Using the Schräge Musik required precise timing and swift evasion; a fatally damaged bomber could fall on the night fighter if the fighter could not quickly turn away. The He 219 was particularly prone to this; its high wing loading left it at the edge of stalling speed when matching the Lancaster's cruising speed, and therefore quite unmaneuverable. The same was true to a lesser extent of other Luftwaffe types such as the Ju 88, which was considered quite a "hot ship" by its crews. This was also a problem during normal stern attacks at low closure rate, but it was even more exaggerated during schräge musik attacks, since the pilot could not even make use of the limited climb performance available at the edge of the flight envelope to avoid debris from the stricken target.

Schräge Musik allowed German night fighters to attack undetected, using special ammunition with a faint glowing trail replacing the standard tracer, combined with a "lethal mixture of armour-piercing, explosive and incendiary ammunition."[20] Approaching from below provided the night fighter crew with the advantage that the bomber crew could not see them against the dark ground or sky, yet allowed the German crew to see the silhouette of the aircraft before they attacked. The optimum target for the night fighter was the wing fuel tanks, not the fuselage or bomb bay, because of the risk that exploding bombs would damage the attacker. "To overcome some of the problems, many NJG pilots closed the range at a lower level, below the Monica zone of coverage, until they could see the bomber above; then they pulled up into a climb with all front guns blazing. This demanded fine judgement, gave only a second or two of firing time and almost immediately brought the fighter up behind the bomber's tail turret.

Schräge Musik produced devastating results, with its most successful deployment in the winter of 1943–1944. This was a time when Bomber Command losses became unsupportable: the RAF lost 78 of 823 bombers that attacked Leipzig on 19 February, and 96 of the 795 bombers that attacked Nuremberg on 30/31 March 1944. RAF Bomber Command was slow to react to the threat from Schräge Musik, with no reports from shot-down crews reporting the new tactic; the sudden increase in bomber losses had often been attributed to flak. Reports from air gunners of German night fighters stalking their prey from below had appeared as early as 1943 but had been discounted. A myth developed among RAF Bomber Command crews that "scarecrow shells" were encountered over Germany. The phenomenon was thought to be "AA shells simulating an exploding four-engined bomber and designed to damage morale. In many cases these were actual 'kills' by Luftwaffe night fighters... It was not for many months that evidence of these deadly attacks was accepted."[21]

A detailed analysis of the damage done to returning bombers clearly showed that the night fighters were firing from below. Defence against the attacks included mixing de Havilland Mosquito night fighters into the bomber stream, to pick up radar emissions from the German night fighters.[15] Wing Commander J. D. Pattinson of 429 "Bison" Squadron, recognized an unseen danger but to him, it "was all presumption, not fact." He ordered that the mid-upper turrets be removed and the "displaced gunner would lie on a mattress on the floor as an observer, looking through a perspex blister for night fighters coming up from below."[10] Some early Lancaster B. IIs had retained the FN.64 ventral turret but its sighting periscope provided an overly tight field of view that left the gunner blind, and the traverse speed was too slow, making it useless,[22] and a small number of Halifax and Lancaster bombers were fitted with a machine-gun mounted to fire through the hole where the turret would have been, normally of .303 in (7.70 mm) although Canadian units tended to use the 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine gun. Initially these were unofficial, but Mod 925 provided an official modification in aircraft not equipped with H2S bombing radar, which covered the turret location.[22]

Even in the last year of the war, 18 months after the Peenemunde Raid, Schräge Musik night fighters were still taking a heavy toll, for example on the Mitteland–Ems Canal Raid, 21 February 1945:

On this particular night the night fighters were to score heavily. The ground radar stations responsible for initial guidance to the vicinity of the bombers did their job well, as did the airborne radar operators to whom fell the task of final location of individual targets. The path of the returning bomber stream was clearly marked by the pyres of numerous downed victims. NJG 4 was operating from Gutersloh (later an RAF base) and in the space of 20 minutes, between 20.43 and 21.03, Schnaufer and his crew, using their upward firing cannons [from a Bf 110G night fighter], shot down seven Lancasters. As it was, on that black night, four night fighter crews accounted for 28 of the 62 bombers lost out of the 800 despatched.[23]

Japan

In 1943, Commander Yasuna Kozono of the 251st Kōkūtai, Imperial Japanese Navy in Rabaul came up with the idea of converting the Nakajima J1N (J1N1-C) Irving into a night fighter. On 21 May 1943, at about the same time as the Luftwaffe's Oberleutnant Schoenert had his first victory with Schräge Musik in Europe, the field-modified J1N1-C KAI shot down two B-17s of the 43rd Bomb Group who were attacking air bases around Rabaul. The Navy took immediate notice and placed orders with Nakajima, for the newly designated J1N1-S night fighter design. This model was christened the Model 11 Gekkō (月光, Moonlight). It required only two crew and like the KAI, had a 20-millimetre (0.79 in)-calibre twinned pair of Type 99 Model 1 cannon firing upward and a second pair firing downward at a forward 30° angle, also placed in the fuselage behind the cabin. The Type 99 20mm calibre autocannon ordnance used by Japanese aircraft was based on the drum-magazine fed Swiss Oerlikon FF ordnance which was itself the basis for the Germans' own MG FF weapon, used to pioneer Schräge Musik for the Luftwaffe.

The Japanese Army Air Force Mitsubishi Ki-46 "Dinah" twin engined fighter was used to test the Schräge Musik armament format in its Ki-46 III KAI version in June 1943, using a 37 mm Ho-203 cannon with 200 rounds of ammunition, the largest calibre autocannon used for Schräge Musik-type operations. It was mounted in a similar position in the fuselage as the Luftwaffe's night fighters. Operational deployment began in October 1944.[24]

_Type_2_Toryu_(Dragon_Killer)_NICK.jpg.webp)

One of the main Japanese fighters using this device was the Kawasaki Ki-45 "Nick". With the Schräge Musik installation on the IJNAS's Nakajima J1N1-S "Gekkō" (two or three 20mm cannons firing upwards, some had two firing downwards), the Nakajima C6N1-S "Myrt" single-engined, high-speed reconnaissance aircraft was used with a pair of 20 mm Type 99 cannons.[25]

One variant of the common A6M5 Zero single-seat fighter—the A6M5d-S—had a 20mm Type 99 cannon mounted just behind the pilot, firing upwards for night fighter combat.

United Kingdom

Air Ministry Specification F.9/37 led to the second, Rolls-Royce Peregrine powered, prototype of the Gloster G39 having its armament installed at an angle of +12° for 'no-allowance' firing – three dorsal 20mm cannon in the fuselage and two in the nose.[26] While it was a promising aircraft in its own right, by the time that the second prototype was completed the conventionally-armed Bristol Beaufighter was already in production, so neither the G39 nor the subsequent Gloster Reaper were pursued.

Similar logic lay behind Air Ministry specification F11/37, which specified a turret-mounted cannon armament: of three companies who tendered (Armstrong Whitworth and Bristol) had turrets that could only traverse through the forward hemisphere, as did Air Ministry specification F22/39, written around the Vickers Type 414 twin-engined fighter, which combined a streamlined monoplane two-seater fighter airframe with a remotely controlled 40mm cannon in the nose that could be elevated for no-allowance shooting.[5]

The Boulton Paul Defiant "turret fighter" was originally conceived under the F.9/35 specification for a "two-seat day and night fighter" to defend Great Britain against massed formations of unescorted enemy bombers.[26] Regardless of the requirement, the use of its dorsal turret was based on the "broadside" fighter interception and combined fighter attack tactic of bomber interception. Attempts to take on single-seat fighters with Defiants led to catastrophic results in 1940 over France and during the Battle of Britain.[28] With such high losses in day operations, the Defiant was transferred to night fighting and there the type achieved some success. Defiant night fighters typically attacked enemy bombers from below, in a similar manoeuvre to the later German Schräge Musik attacks, more often from slightly ahead or to one side, rather than from directly under the tail. During the Blitz on London of 1940–1941, the Defiant equipped four squadrons, shooting down more enemy aircraft than any other type.[29] The Defiant Mk II was fitted with AI.IV radar and a Merlin XX engine. A total of 207 Defiant Mk IIs were built but the Defiant was retired as radar-equipped Beaufighter and Mosquito night fighters entered service in 1941 and 1942.[30] Turret fighters with four 20mm cannon were specified under F.11/37 but got no further than a scaled prototype.[31]

A Douglas Havoc, BD126, was fitted with six upward firing machine guns in the fuselage behind the cockpit. The guns could be controlled in elevation from 30–50 degrees and 15 degrees in the azimuth by the gunner in the nose. The aircraft was tested at the A&AEE in 1941 and then by the GRU and Fighter Interception Unit.[32]

United States

The American Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter could deliver a Schräge Musik-like surprise of its own, because of the design of its remote dorsal turret carrying a quartet of .50 Caliber Browning M2 machine guns, that could elevate to a full 90° position.

Postwar

The Northrop F-89 Scorpion was originally designed to meet the 1945 United States Army Air Forces Army Air Technical Service Command specification ("Military Characteristics for All-Weather Fighting Aircraft") for a jet-powered night fighter to replace the P-61 Black Widow. The N-24 company proposal was armed with four 20 mm (.79 in) cannon in a unique trainable nose turret that could rotate 360˚ with the guns able to elevate to 105˚.[33] Ultimately, the F-89 design abandoned the swiveling nose turret in favor of a more standard front-firing cannon arrangement.[34] A similar design – with .50 caliber machine guns – would also be tested on a United States Navy Grumman F9F Panther.[35]

In 1947, the United States Air Force tested a Schräge Musik gun installation on a Lockheed F-80A Shooting Star standard "day fighter" aircraft (s/n 44-85044) to study the ability to attack Soviet bombers from below. Twin 0.5 in (12.7 mm) machine guns were fixed in an oblique mount.[36]

A final attempt to exploit a fully traversing turret was found in the original 1948 design of the Curtiss-Wright XF-87 Blackhawk all-weather jet fighter interceptor. Armament was to be a nose-mounted, powered turret containing four 20 mm (.79 in) cannon, but this installation was only fitted to the mock-up and never incorporated in the two prototypes.[37]

In the Soviet Union the concept lasted slightly longer, with elevatable guns being tested on a Mikoyan MiG-17 in the early 1950s.[38]

Analysis

Freeman Dyson, who was an analyst for Operations research of RAF Bomber Command in World War II, commented on the effectiveness of Schräge Musik:

The cause of losses... killed novice and expert crews impartially. This result contradicted the official dogma... I blame the ORS and I blame myself in particular, for not taking this result seriously enough... If we had taken the evidence more seriously, we might have discovered Schräge Musik in time to respond with effective countermeasures.

— Freeman Dyson[39]

References

Notes

- The COW 37 mm was also tried on flying boats, for use against naval vessels.

- Monica, developed at the Bomber Support Development Unit in Worcestershire, was a range-only tail warning radar for bombers, introduced by the RAF in the spring of 1942. Officially known as ARI 5664, it operated at frequencies of around 300 MHz. German night fighters equipped with special detectors could home in on Monica and after July 1944, the units were removed from RAF bombers.

- Peenemünde is a village in the north-west of the German island of Usedom on the Peene river, on the easternmost part of the German Baltic coast.

Citations

- Wilson 2008, p. 3.

- Mason 1997, pp. 111–112.

- Andrews and Morgan 1988, pp. 242–246.

- James 1991, pp. 198–199.

- Sinnott, Colin (2001). The RAF and Aircraft Design, 1923–1939: Air Staff Operational Requirements. Frank Cass. ISBN 0714651583.

- Mondey 2002, p. 41.

- Winchester 2005, p. 74.

- Norton 2008, p. 123.

- Aders 1979, p. 67.

- "Schräge Musik & The Wesseling Raid: 21/22 June 1944." 207 Squadron Royal Air Force Association. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- Hastings 1999, p. 45.

- de Bie, Rob. "Komet weapons: SG500 Jägerfaust." xs4all.nl. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- "Hitler's Stealth Fighter Re-created." National Geographic, 25 June 2009. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- Bowers 1982, p. 20.

- Gunston 2004, p. 98.

- "Leonard Isaacson." Ex Air Gunners, July 2001. Retrieved: 1 October 2010.

- 'The Peenemünde Raid', Martin Middlebrook (Phoenix 2000)

- Mondey 2006, p. 97.

- Aders 1979, pp. 137, 190.

- Hincliffe 1996, p. 138.

- "Blundering to victory... aviation technology vs the Allied establishment in WW2." BBC, 23 June 2001. Retrieved: 1 October 2010.

- "Avro 683 Lancaster: The most iconic heavy bomber of World War II". BAE Systems. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- Mason 1989, p. 157.

- Mondey 2006, p. 209.

- Mondey 2006, pp. 218–220.

- Buttler 2004, p. 51.

- Bowyer 1970, p. 270.

- Mondey 2002, pp. 40–41.

- Taylor 1969, p. 326.

- Scutts 1993, pp. 4–5.

- Buttler (2004) pp. 56–59

- Mason 1998, p. 56.

- Davis and Menard 1990, pp. 4–5.

- Air International, July 1988, p. 46.

- Thomason, Tommy H. (22 March 2013). "The Emerson Fighter Turret". Tailhook Topics. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star." aviationspectator.com. Retrieved: 28 September 2010.

- Boyne 1975, p. 36.

- Belyakov, R. A.; Marmain, J. (1994). MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 189–193.

- Dyson, F. "A Failure of Intelligence." Technology Review, Nov–Dec 2006. Retrieved: 23 March 2023.

Bibliography

- Aders, Gebhard. History of the German Night Fighter Force 1917–45. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1979. ISBN 978-0-354-01247-8.

- Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan'. Vickers Aircraft since 1908. London: Putnam, 2nd ed., 1988. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.

- Boyne, Walt. "A Fighter for All Weather... Curtiss XP-87 Blackhawk." Wings, Vol. 5, No. 1, February 1975.

- Bowers, Peter W. "Junkers Ju 88: Demon in the Dark." Wings, Vol. 12, No. 2, August 1982.

- Bruce, J.M. Warplanes of the First World War, Volume Three: Fighters. London: Macdonald, 1969. ISBN 0-356-01490-8.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters & Bombers 1935–1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Bowyer, Michael J.F. "The Boulton Paul Defiant." Aircraft in Profile, Vol. 5. London, Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Davis, Larry and Dave Menard. F-89 Scorpion in action (Aircraft Number 104). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1990. ISBN 0-89747-246-2.

- Gunston, Bill. Night Fighters: A Development and Combat History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, First edition 1976. ISBN 978-0-7509-3410-7.

- Hastings, Sir Max. Bomber Command (Pan Grand Strategy Series). London: Pan Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0-330-39204-4.

- Hinchliffe, Peter. Other Battle: Luftwaffe Night Aces vs. Bomber Command. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7603-0265-1.

- James, Derek N. Westland Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-847-X.

- Mason, Francis K. The Avro Lancaster. Bucks, UK: Ashton Publications Ltd., First edition 1989. ISBN 978-0-946627-30-1

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter Since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1977. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.

- Mason, Tim. The Secret Years: Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939–1945. Crowborough, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2010, First edition 1998. ISBN 978-1-90210-914-5.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Bounty Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7537-1460-4.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to British Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor Press, 2002. ISBN 1-85152-668-4.

- Norton, Bill. U.S. Experimental & Prototype Aircraft Projects: Fighters 1939–1945. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58007-109-3.

- "Scorpion with a Nuclear Sting: Northrop F-89". Air International, July 1988, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 44–50. Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Scutts, Jerry. Mosquito in Action, Part 1. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1993. ISBN 0-89747-285-3.

- Taylor, James and Martin Davidson. Bomber Crew. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 2004. ISBN 978-0-340-83871-6.

- Taylor, John W.R. "Boulton Paul Defiant." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Thompson, Warren. P-61 Black Widow Units of World War 2 (Osprey Combat Aircraft 8). Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1998. ISBN 978-1-85532-725-2.

- Wilson, Kevin. Men Of Air: The Doomed Youth Of Bomber Command (Bomber War Trilogy 2). London: Phoenix, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7538-2398-9.

- Winchester, Jim. "Bell YFM-1 Airacuda". The World's Worst Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2005. ISBN 1-904687-34-2.