Screenwriting

Screenwriting or scriptwriting is the art and craft of writing scripts for mass media such as feature films, television productions or video games. It is often a freelance profession.

Screenwriters are responsible for researching the story, developing the narrative, writing the script, screenplay, dialogues and delivering it, in the required format, to development executives. Screenwriters therefore have great influence over the creative direction and emotional impact of the screenplay and, arguably, of the finished film. Screenwriters either pitch original ideas to producers, in the hope that they will be optioned or sold; or are commissioned by a producer to create a screenplay from a concept, true story, existing screen work or literary work, such as a novel, poem, play, comic book, or short story.

Types

The act of screenwriting takes many forms across the entertainment industry. Often, multiple writers work on the same script at different stages of development with different tasks. Over the course of a successful career, a screenwriter might be hired to write in a wide variety of roles.

Some of the most common forms of screenwriting jobs include:

Spec script writing

Spec scripts are feature film or television show scripts written on speculation of sale, without the commission of a film studio, production company, or TV network. The content is usually invented solely by the screenwriter, though spec screenplays can also be based on established works or real people and events. The spec script is a Hollywood sales tool. The vast majority of scripts written each year are spec scripts, but only a small percentage make it to the screen.[1] A spec script is usually a wholly original work, but can also be an adaptation.

In television writing, a spec script is a sample teleplay written to demonstrate the writer's knowledge of a show and ability to imitate its style and conventions. It is submitted to the show's producers in hopes of being hired to write future episodes of the show. Budding screenwriters attempting to break into the business generally begin by writing one or more spec scripts.

Although writing spec scripts is part of any writer's career, the Writers Guild of America forbids members to write "on speculation". The distinction is that a "spec script" is written as a sample by the writer on his or her own; what is forbidden is writing a script for a specific producer without a contract. In addition to writing a script on speculation, it is generally not advised to write camera angles or other directional terminology, as these are likely to be ignored. A director may write up a shooting script himself or herself, a script that guides the team in what to do in order to carry out the director's vision of how the script should look. The director may ask the original writer to co-write it with him or her or to rewrite a script that satisfies both the director and producer of the film/TV show.

Spec writing is also unique in that the writer must pitch the idea to producers. In order to sell the script, it must have an excellent title, good writing, and a great logline. A logline is one sentence that lays out what the movie is about. A well-written logline will convey the tone of the film, introduce the main character, and touch on the primary conflict. Usually the logline and title work in tandem to draw people in, and it is highly suggested to incorporate irony into them when possible. These things, along with nice, clean writing will hugely impact whether or not a producer picks up the spec script.

Commission

A commissioned screenplay is written by a hired writer. The concept is usually developed long before the screenwriter is brought on, and often has multiple writers work on it before the script is given a green light. The plot development is usually based on highly successful novels, plays, TV shows, and even video games, and the rights to which have been legally acquired.

Feature assignment writing

Scripts written on assignment are screenplays created under contract with a studio, production company, or producer. These are the most common assignments sought after in screenwriting. A screenwriter can get an assignment either exclusively or from "open" assignments. A screenwriter can also be approached and offered an assignment. Assignment scripts are generally adaptations of an existing idea or property owned by the hiring company,[2] but can also be original works based on a concept created by the writer or producer.

Rewriting and script doctoring

Most produced films are rewritten to some extent during the development process. Frequently, they are not rewritten by the original writer of the script.[3] Many established screenwriters, as well as new writers whose work shows promise but lacks marketability, make their living rewriting scripts.

When a script's central premise or characters are good but the script is otherwise unusable, a different writer or team of writers is contracted to do an entirely new draft, often referred to as a "page one rewrite". When only small problems remain, such as bad dialogue or poor humor, a writer is hired to do a "polish" or "punch-up".

Depending on the size of the new writer's contributions, screen credit may or may not be given. For instance, in the American film industry, credit to rewriters is given only if 50% or more of the script is substantially changed.[4] These standards can make it difficult to establish the identity and number of screenwriters who contributed to a film's creation.

When established writers are called in to rewrite portions of a script late in the development process, they are commonly referred to as script doctors. Prominent script doctors include Christopher Keane, Steve Zaillian, William Goldman, Robert Towne, Mort Nathan, Quentin Tarantino and Peter Russell.[5] Many up-and-coming screenwriters work as ghostwriters.

Television writing

A freelance television writer typically uses spec scripts or previous credits and reputation to obtain a contract to write one or more episodes for an existing television show. After an episode is submitted, rewriting or polishing may be required.

A staff writer for a TV show generally works in-house, writing and rewriting episodes. Staff writers— often given other titles, such as story editor or producer— work both as a group and individually on episode scripts to maintain the show's tone, style, characters, and plots.[6]

Television show creators write the television pilot and bible of new television series. They are responsible for creating and managing all aspects of a show's characters, style, and plots. Frequently, a creator remains responsible for the show's day-to-day creative decisions throughout the series run as showrunner, head writer, or story editor.

Writing for daily series

The process of writing for soap operas and telenovelas is different from that used by prime time shows, due in part to the need to produce new episodes five days a week for several months. In one example cited by Jane Espenson, screenwriting is a "sort of three-tiered system":[7]

- a few top writers craft the overall story arcs. Mid-level writers work with them to turn those arcs into things that look a lot like traditional episode outlines, and an array of writers below that (who do not even have to be local to Los Angeles), take those outlines and quickly generate the dialogue while adhering slavishly to the outlines.

Espenson notes that a recent trend has been to eliminate the role of the mid-level writer, relying on the senior writers to do rough outlines and giving the other writers a bit more freedom. Regardless, when the finished scripts are sent to the top writers, the latter do a final round of rewrites. Espenson also notes that a show that airs daily, with characters who have decades of history behind their voices, necessitates a writing staff without the distinctive voice that can sometimes be present in prime-time series.[7]

Writing for game shows

Game shows feature live contestants, but still use a team of writers as part of a specific format.[8] This may involve the slate of questions and even specific phrasing or dialogue on the part of the host. Writers may not script the dialogue used by the contestants, but they work with the producers to create the actions, scenarios, and sequence of events that support the game show's concept.

Video game writing

With the continued development and increased complexity of video games, many opportunities are available to employ screenwriters in the field of video game design. Video game writers work closely with the other game designers to create characters, scenarios, and dialogue.[9]

Structural theories

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History and lists | ||||||

| Discussion | ||||||

| Topics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Several main screenwriting theories help writers approach the screenplay by systematizing the structure, goals and techniques of writing a script. The most common kinds of theories are structural. Screenwriter William Goldman is widely quoted as saying "Screenplays are structure".

Three-act structure

According to this approach, the three acts are: the setup (of the setting, characters, and mood), the confrontation (with obstacles), and the resolution (culminating in a climax and a dénouement). In a two-hour film, the first and third acts each last about thirty minutes, with the middle act lasting about an hour, but nowadays many films begin at the confrontation point and segue immediately to the setup or begin at the resolution and return to the setup.

In Writing Drama, French writer and director Yves Lavandier shows a slightly different approach.[10] As do most theorists, he maintains that every human action, whether fictitious or real, contains three logical parts: before the action, during the action, and after the action. But since the climax is part of the action, Lavandier maintains that the second act must include the climax, which makes for a much shorter third act than is found in most screenwriting theories.

Besides the three-act structure, it is also common to use a four- or five-act structure in a screenplay, and some screenplays may include as many as twenty separate acts.

The Hero's Journey

The hero's journey, also referred to as the monomyth, is an idea formulated by noted mythologist Joseph Campbell. The central concept of the monomyth is that a pattern can be seen in stories and myths across history. Campbell defined and explained that pattern in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949).[11]

Campbell's insight was that important myths from around the world, which have survived for thousands of years, all share a fundamental structure. This fundamental structure contains a number of stages, which include:

- a call to adventure, which the hero has to accept or decline,

- a road of trials, on which the hero succeeds or fails,

- achieving the goal (or "boon"), which often results in important self-knowledge,

- a return to the ordinary world, which again the hero can succeed or fail, and

- application of the boon, in which what the hero has gained can be used to improve the world.

Later, screenwriter Christopher Vogler refined and expanded the hero's journey for the screenplay form in his book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1993).[12]

Syd Field's paradigm

Syd Field introduced a new theory he called "the paradigm".[13] He introduced the idea of a plot point into screenwriting theory[14] and defined a plot point as "any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins it around in another direction".[15] These are the anchoring pins of the story line, which hold everything in place.[16] There are many plot points in a screenplay, but the main ones that anchor the story line in place and are the foundation of the dramatic structure, he called plot points I and II.[17][18] Plot point I occurs at the end of Act 1; plot point II at the end of Act 2.[14] Plot point I is also called the key incident because it is the true beginning of the story[19] and, in part, what the story is about.[20]

In a 120-page screenplay, Act 2 is about sixty pages in length, twice the length of Acts 1 and 3.[21] Field noticed that in successful movies, an important dramatic event usually occurs at the middle of the picture, around page sixty. The action builds up to that event, and everything afterward is the result of that event. He called this event the centerpiece or midpoint.[22] This suggested to him that the middle act is actually two acts in one. So, the three-act structure is notated 1, 2a, 2b, 3, resulting in Aristotle’s three acts being divided into four pieces of approximately thirty pages each.[23]

Field defined two plot points near the middle of Acts 2a and 2b, called pinch I and pinch II, occurring around pages 45 and 75 of the screenplay, respectively, whose functions are to keep the action on track, moving it forward, either toward the midpoint or plot point II.[24] Sometimes there is a relationship between pinch I and pinch II: some kind of story connection.[25]

According to Field, the inciting incident occurs near the middle of Act 1,[26] so-called because it sets the story into motion and is the first visual representation of the key incident.[27] The inciting incident is also called the dramatic hook, because it leads directly to plot point I.[28]

Field referred to a tag, an epilogue after the action in Act 3.[29]

Here is a chronological list of the major plot points that are congruent with Field's Paradigm:

| What | Characterization | Example: Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope |

|---|---|---|

| Opening image | The first image in the screenplay should summarize the entire film, especially its tone. Screenwriters often go back and redo this as their final task before submitting the script. | In outer space, near the planet Tatooine, an Imperial Star Destroyer pursues and exchanges fire with a Rebel Tantive IV spaceship. |

| Exposition | This provides some background information to the audience about the plot, characters' histories, setting, and theme. The status quo or ordinary world of the protagonist is established. | The settings of space and the planet Tatooine are shown; the rebellion against the Empire is described; and many of the main characters are introduced: C-3PO, R2-D2, Princess Leia Organa, Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker (the protagonist), and Ben Kenobi (Obi-Wan Kenobi). Luke's status quo is his life on his Uncle's moisture farm. |

| Inciting incident | Also known as the catalyst or disturbance, this is something bad, difficult, mysterious, or tragic that catalyzes the protagonist to go into motion and take action: the event that starts the protagonist on the path toward the conflict. | Luke sees the tail end of the hologram of Princess Leia, which begins a sequence of events that culminates in plot point I. |

| Plot point I | Also known as the first doorway of no return, or the first turning point, this is the last scene in Act 1, a surprising development that radically changes the protagonist's life, and forces him or her to confront the opponent. Once the protagonist passes through this one-way door, he or she cannot go back to his or her status quo. | This is when Luke's uncle and aunt are killed and their home is destroyed by the Empire. He has no home to go back to, so he joins the Rebels in opposing Darth Vader. Luke's goal at this point is to help the princess. |

| Pinch I | A reminder scene at about 3/8 of the way through the script (halfway through Act 2a) that brings up the central conflict of the drama, reminding the audience of the overall conflict. | Imperial stormtroopers attack the Millennium Falcon in Mos Eisley, reminding the audience the Empire is after the stolen Death Star plans that R2-D2 is carrying, and Luke and Ben Kenobi are trying to get to the Rebel base. |

| Midpoint | An important scene in the middle of the script, often a reversal of fortune or revelation that changes the direction of the story. Field suggests that driving the story toward the midpoint keeps the second act from sagging. | Luke and his companions learn that Princess Leia is aboard the Death Star. Now that Luke knows where the princess is, his new goal is to rescue her. |

| Pinch II | Another reminder scene about 5/8 of the way through the script (halfway through Act 2b) that is somehow linked to pinch I in reminding the audience about the central conflict. | After surviving the garbage masher, Luke and his companions clash with stormtroopers again in the Death Star while en route to the Millennium Falcon. Both scenes remind us of the Empire's opposition, and using the stormtrooper attack motif unifies both pinches. |

| Plot point II | A dramatic reversal that ends Act 2 and begins Act 3. | Luke, Leia, and their companions arrive at the Rebel base. Now that the princess has been successfully rescued, Luke's new goal is to assist the Rebels in attacking the Death Star. |

| Moment of truth | Also known as the decision point, the second doorway of no return, or the second turning point, this is the point, about midway through Act 3, when the protagonist must make a decision. The story is, in part, about what the main character decides at the moment of truth. The right choice leads to success; the wrong choice to failure. | Luke must choose between trusting his mind or trusting The Force. He makes the right choice to let go and use the Force. |

| Climax | The point of highest dramatic tension in the action, which immediately follows the moment of truth. The protagonist confronts the main problem of the story and either overcomes it, or comes to a tragic end. | Luke’s proton torpedoes hit the target, and he and his companions leave the Death Star. |

| Resolution | The issues of the story are resolved. | The Death Star explodes. |

| Tag | An epilogue, tying up the loose ends of the story, giving the audience closure. This is also known as denouement. Films in recent decades have had longer denouements than films made in the 1970s or earlier. | Leia awards Luke and Han medals for their heroism. |

The sequence approach

The sequence approach to screenwriting, sometimes known as "eight-sequence structure", is a system developed by Frank Daniel, while he was the head of the Graduate Screenwriting Program at USC. It is based in part on the fact that, in the early days of cinema, technical matters forced screenwriters to divide their stories into sequences, each the length of a reel (about ten minutes).[30]

The sequence approach mimics that early style. The story is broken up into eight 10-15 minute sequences. The sequences serve as "mini-movies", each with their own compressed three-act structure. The first two sequences combine to form the film's first act. The next four create the film's second act. The final two sequences complete the resolution and dénouement of the story. Each sequence's resolution creates the situation which sets up the next sequence.

Character theories

Michael Hauge's categories

Michael Hauge divides primary characters into four categories. A screenplay may have more than one character in any category.

- hero: This is the main character, whose outer motivation drives the plot forward, who is the primary object of identification for the reader and audience, and who is on screen most of the time.

- nemesis: This is the character who most stands in the way of the hero achieving his or her outer motivation.

- reflection: This is the character who supports the hero's outer motivation or at least is in the same basic situation at the beginning of the screenplay.

- romance: This is the character who is the sexual or romantic object of at least part of the hero's outer motivation.[31]

Secondary characters are all the other people in the screenplay and should serve as many of the functions above as possible.[32]

Motivation is whatever the character hopes to accomplish by the end of the movie. Motivation exists on outer and inner levels.

- outer motivation is what the character visibly or physically hopes to achieve or accomplish by the end of the film. Outer motivation is revealed through action.

- inner motivation is the answer to the question, "Why does the character want to achieve his or her outer motivation?" This is always related to gaining greater feelings of self-worth. Since inner motivation comes from within, it is usually invisible and revealed through dialogue. Exploration of inner motivation is optional.

Motivation alone is not sufficient to make the screenplay work. There must be something preventing the hero from getting what he or she wants. That something is conflict.

- outer conflict is whatever stands in the way of the character achieving his or her outer motivation. It is the sum of all the obstacles and hurdles that the character must try to overcome in order to reach his or her objective.

- inner conflict is whatever stands in the way of the character achieving his or her inner motivation. This conflict always originates from within the character and prevents him or her from achieving self-worth through inner motivation.[33]

Format

Fundamentally, the screenplay is a unique literary form. It is like a musical score, in that it is intended to be interpreted on the basis of other artists' performance, rather than serving as a finished product for the enjoyment of its audience. For this reason, a screenplay is written using technical jargon and tight, spare prose when describing stage directions. Unlike a novel or short story, a screenplay focuses on describing the literal, visual aspects of the story, rather than on the internal thoughts of its characters. In screenwriting, the aim is to evoke those thoughts and emotions through subtext, action, and symbolism.[34]

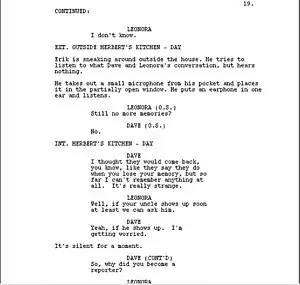

Most modern screenplays, at least in Hollywood and related screen cultures, are written in a style known as the master-scene format[35][36] or master-scene script.[37] The format is characterized by six elements, presented in the order in which they are most likely to be used in a script:

- Scene Heading, or Slug

- Action Lines, or Big Print

- Character Name

- Parentheticals

- Dialogue

- Transitions

Scripts written in master-scene format are divided into scenes: "a unit of story that takes place at a specific location and time".[38] Scene headings (or slugs) indicate the location the following scene is to take place in, whether it is interior or exterior, and the time-of-day it appears to be. Conventionally, they are capitalized, and may be underlined or bolded. In production drafts, scene headings are numbered.

Next are action lines, which describe stage direction and are generally written in the present tense with a focus only on what can be seen or heard by the audience.

Character names are in all caps, centered in the middle of the page, and indicate that a character is speaking the following dialogue. Characters who are speaking off-screen or in voice-over are indicated by the suffix (O.S.) and (V.O) respectively.

Parentheticals provide stage direction for the dialogue that follows. Most often this is to indicate how dialogue should be performed (for example, angry) but can also include small stage directions (for example, picking up vase). Overuse of parentheticals is discouraged.[39]

Dialogue blocks are offset from the page's margin by 3.7" and are left-justified. Dialogue spoken by two characters at the same time is written side by side and is conventionally known as dual-dialogue.[40]

The final element is the scene transition and is used to indicate how the current scene should transition into the next. It is generally assumed that the transition will be a cut, and using "CUT TO:" will be redundant.[41][42] Thus the element should be used sparingly to indicate a different kind of transition such as "DISSOLVE TO:".

Screenwriting applications such as Final Draft (software), Celtx, Fade In (software), Slugline, Scrivener (software), and Highland, allow writers to easily format their script to adhere to the requirements of the master screen format.

Dialogue and description

Imagery

Imagery can be used in many metaphoric ways. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, the title character talked of wanting to close the door on himself sometime, and then, in the end, he did. Pathetic fallacy is also frequently used; rain to express a character feeling depressed, sunny days promote a feeling of happiness and calm. Imagery can be used to sway the emotions of the audience and to clue them in to what is happening.

Imagery is well defined in City of God. The opening image sequence sets the tone for the entire film. The film opens with the shimmer of a knife's blade on a sharpening stone. A drink is being prepared, The knife's blade shows again, juxtaposed is a shot of a chicken letting loose of its harness on its feet. All symbolising 'The One that got away'. The film is about life in the favelas in Rio - sprinkled with violence and games and ambition.

Dialogue

Since the advent of sound film, or "talkies", dialogue has taken a central place in much of mainstream cinema. In the cinematic arts, the audience understands the story only through what they see and hear: action, music, sound effects, and dialogue. For many screenwriters, the only way their audiences can hear the writer's words is through the characters' dialogue. This has led writers such as Diablo Cody, Joss Whedon, and Quentin Tarantino to become well known for their dialogue—not just their stories.

Bollywood and other Indian film industries use separate dialogue writers in addition to the screenplay writers.[43]

Plot

Plot, according to Aristotle's Poetics, refers to the sequence events connected by cause and effect in a story. A story is a series of events conveyed in chronological order. A plot is the same series of events deliberately arranged to maximize the story's dramatic, thematic, and emotional significance. E.M.Forster famously gives the example "The king died and then the queen died" is a story." But "The king died and then the queen died of grief" is a plot.[44] For Trey Parker and Matt Stone this is best summarized as a series of events connected by "therefore" and "but".[45]

Education

A number of American universities offer specialized Master of Fine Arts and undergraduate programs in screenwriting, including USC, DePaul University, American Film Institute, Loyola Marymount University, Chapman University, NYU, UCLA, Boston University and the University of the Arts. In Europe, the United Kingdom has an extensive range of MA and BA Screenwriting Courses including London College of Communication, Bournemouth University, Edinburgh University, and Goldsmiths College (University of London).

Some schools offer non-degree screenwriting programs, such as the TheFilmSchool, The International Film and Television School Fast Track, and the UCLA Professional / Extension Programs in Screenwriting.

New York Film Academy offers both degree and non-degree educational systems with campuses all around the world.

A variety of other educational resources for aspiring screenwriters also exist, including books, seminars, websites and podcasts, such as the Scriptnotes podcast.

History

The first true screenplay is thought to be from George Melies' 1902 film A Trip to the Moon. The movie is silent, but the screenplay still contains specific descriptions and action lines that resemble a modern-day script. As time went on and films became longer and more complex, the need for a screenplay became more prominent in the industry. The introduction of movie theaters also impacted the development of screenplays, as audiences became more widespread and sophisticated, so the stories had to be as well. Once the first non-silent movie was released in 1927, screenwriting became a hugely important position within Hollywood. The "studio system" of the 1930s only heightened this importance, as studio heads wanted productivity. Thus, having the "blueprint" (continuity screenplay) of the film beforehand became extremely optimal. Around 1970, the "spec script" was first created, and changed the industry for writers forever. Now, screenwriting for television (teleplays) is considered as difficult and competitive as writing is for feature films.[46]

Portrayed in film

Screenwriting has been the focus of a number of films:

- Crashing Hollywood (1931)—A screenwriter collaborates on a gangster movie with a real-life gangster. When the film is released, the mob does not like how accurate the movie is.[47]

- Sunset Boulevard (1950)—Actor William Holden portrays a hack screenwriter forced to collaborate on a screenplay with a desperate, fading silent film star, played by Gloria Swanson.

- In a Lonely Place (1950)—Humphrey Bogart is a washed up screenwriter who gets framed for murder.

- Paris, When it Sizzles (1964)—William Holden plays a drunk screenwriter who has wasted months partying and has just two days to finish his script. He hires Audrey Hepburn to help.

- Barton Fink (1991)—John Turturro plays a naïve New York playwright who comes to Hollywood with high hopes and great ambition. While there, he meets one of his writing idols, a celebrated novelist from the past who has become a drunken hack screenwriter (a character based on William Faulkner).

- Mistress (1992)—In this comedy written by Barry Primus and J. F. Lawton, Robert Wuhl is a screenwriter/director who's got integrity, vision, and a serious script — but no career. Martin Landau is a sleazy producer who introduces Wuhl to Robert De Niro, Danny Aiello and Eli Wallach - three guys willing to invest in the movie, but with one catch: each one wants his mistress to be the star.

- The Player (1992)—In this satire of the Hollywood system, Tim Robbins plays a movie producer who thinks he's being blackmailed by a screenwriter whose script was rejected.

- Adaptation (2002)—Nicolas Cage portrays real-life screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (as well as his fictional brother, Donald) as Kaufman struggles to adapt an esoteric book (Susan Orlean’s real-life nonfiction work The Orchid Thief ) into an action-filled Hollywood screenplay.[48]

- Dreams on Spec (2007)—The only documentary to follow aspiring screenwriters as they struggle to turn their scripts into movies, the film also features wisdom from established scribes like James L. Brooks, Nora Ephron, Carrie Fisher, and Gary Ross.[49]

- Seven Psychopaths (2012)—In this satire, written and directed by Martin McDonagh, Colin Farrell plays a screenwriter who is struggling to finish his screenplay Seven Psychopaths, but finds unlikely inspiration after his best friend steals a Shih Tzu owned by a vicious gangster.

- Trumbo (2015)—Highly successful Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, played in this biopic by Bryan Cranston, is targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee for his socialist views, sent to federal prison for refusing to cooperate, and blacklisted from working in Hollywood, yet continues to write and subsequently wins two Academy Awards while using pseudonyms.

Copyright protection

United States

In the United States, completed works may be copyrighted, but ideas and plots may not be. Any document written after 1978 in the U.S. is automatically copyrighted even without legal registration or notice. However, the Library of Congress will formally register a screenplay. U.S. Courts will not accept a lawsuit alleging that a defendant is infringing on the plaintiff's copyright in a work until the plaintiff registers the plaintiff's claim to those copyrights with the Copyright Office.[50] This means that a plaintiff's attempts to remedy an infringement will be delayed during the registration process.[51] Additionally, in many infringement cases, the plaintiff will not be able recoup attorney fees or collect statutory damages for copyright infringement, unless the plaintiff registered before the infringement began.[52] For the purpose of establishing evidence that a screenwriter is the author of a particular screenplay (but not related to the legal copyrighting status of a work), the Writers Guild of America registers screenplays. However, since this service is one of record keeping and is not regulated by law, a variety of commercial and non-profit organizations exist for registering screenplays. Protection for teleplays, formats, as well as screenplays may be registered for instant proof-of-authorship by third-party assurance vendors.

There is a line of precedent in several states (including California and New York) that allows for "idea submission" claims, based on the notion that submission of a screenplay—or even a mere pitch for one—to a studio under very particular sets of factual circumstances could potentially give rise to an implied contract to pay for the ideas embedded in that screenplay, even if an alleged derivative work does not actually infringe the screenplay author's copyright.[53] The unfortunate side effect of such precedents (which were supposed to protect screenwriters) is that it is now that much harder to break into screenwriting. Naturally, motion picture and television production firms responded by categorically declining to read all unsolicited screenplays from unknown writers;[54] accepting screenplays only through official channels like talent agents, managers, and attorneys; and forcing screenwriters to sign broad legal releases before their screenplays will be actually accepted, read, or considered.[53] In turn, agents, managers, and attorneys have become extremely powerful gatekeepers on behalf of the major film studios and media networks.[54] One symptom of how hard it is to break into screenwriting as a result of such case law is that in 2008, Universal resisted construction of a bike path along the Los Angeles River next to its studio lot because it would worsen their existing problem with desperate amateur screenwriters throwing copies of their work over the studio wall.[55]

See also

References

Specific references

- The Great American Screenplay now fuels wannabe authors from seattlepi.nwsource.com

- Lydia Willen and Joan Willen, How to Sell your Screenplay, pg 242. Square One Publishers, 2001.

- Skip Press, The Ultimate Writer's Guide to Hollywood, pg xiii. Barnes and Noble Books, 2004.

- credits policy from wga.org

- Virginia Wright Wetman. "Success Has 1,000 Fathers (So Do Films)". The New York Times. May 28, 1995. Arts section, p.16.

- TV Writer.com Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine from tvwriter.com

- 08/13/2008: Soapy Scenes, from "Jane in Progress" a blog for aspiring screenwriters by Jane Espenson

- 05/15/2010: Writers Guild of America, Reality & Game Show Writers

- Skip Press, The Ultimate Writer's Guide to Hollywood, pg207. Barnes and Noble Books, 2004.

- Excerpt on the three-act structure from Yves Lavandier's Writing Drama

- Vogler (2007, p. 4)

- Vogler (2007, pp. 6–19)

- Field (2005, p. 21)

- Field (2005, p. 26)

- Field (2006, p. 49)

- Field (1998, p. 33)

- Field (1998, p. 28)

- Field (2005, p. 28)

- Field (1998, p. 30)

- Field (2005, pp. 129, 145)

- Field (2005, p. 90)

- Field (2006, p. 198)

- Field (2006, p. 199)

- Field (2006, p. 222)

- Field (2006, p. 223)

- Field (2005, p. 97)

- Field (2005, p. 129)

- Field (1998, p. 29)

- Field (2005, pp. 101, 103)

- Gulino, Paul Joseph: "Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach", pg3. Continuum, 2003.

- Hauge (1991, pp. 59–62)

- Hauge (1991, p. 65)

- Hauge (1991, pp. 53–58)

- Trottier, David: "The Screenwriter's Bible", pg4. Silman James, 1998.

- "Elements of Screenplay Formatting". ScreenCraft. 2015-05-07. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "Transcript of Scriptnotes, Ep. 138". johnaugust.com. 2014-04-12. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "master scene script - Hollywood Lexicon: lingo & its history". www.hollywoodlexicon.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "What constitutes a scene?". 10 November 2011. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "What is the proper way to use parentheticals?". 13 October 2011. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "How do you format two characters talking at once?". 2 November 2011. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "Can I use "CUT TO:" when moving between scenes? Do I have to?". 5 December 2013. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "Using CUT TO". johnaugust.com. 10 September 2003. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Tyrewala, Abbas (2014-12-11). "Dialogues and screenplay, separated at birth: Abbas Tyrewala". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- Forster, E. M. (1927). Aspects of the Novel. UK: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0156091800.

- Studio, Aerogramme Writers' (2014-03-06). "Writing Advice from South Park's Trey Parker and Matt Stone". Aerogramme Writers' Studio. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- "History". The Art of Screenwriting. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- "Internet Movie Database listing of Crashing Hollywood". IMDb.

- "Interview with Charlie Kaufman". chasingthefrog.com. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10.

- Jay A. Fernandez (July 18, 2007). "Producers, writers face huge chasm: Compensation for digital media and residuals for reuse of content are major issues as contract talks begin". Los Angeles Times.

- 17 USC 411 (United States Code, Title 17, Section 411)

- U.S. Copyright Office Circular 1

- 17 USC 412

- Donald E. Biederman; Edward P. Pierson; Martin E. Silfen; Janna Glasser; Charles J. Biederman; Kenneth J. Abdo; Scott D. Sanders (November 2006). Law and Business of the Entertainment Industries (5th ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 313–327. ISBN 9780275992057.

- Rosman, Kathleen (22 January 2010). "The Death of the Slush Pile". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Hymon, Steve; Andrew Blankstein (27 February 2008). "Studio poses obstacle to riverfront bike path". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

General references

- Edward Azlant (1997). "Screenwriting for the Early Silent Film: Forgotten Pioneers, 1897–1911". Film History. 9 (3): 228–256. JSTOR 3815179.

- Field, Syd (2005). Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting (revised ed.). New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-385-33903-8.

- Field, Syd (1998). The Screenwriter's Problem Solver: How to Recognize, Identify, and Define Screenwriting Problems. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-440-50491-0.

- Field, Syd (2006). The Screenwriter's Workbook (revised ed.). New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-385-33904-6.

- Judith H. Haag, Hillis R. Cole (1980). The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats: The Screenplay. CMC Publishing. ISBN 0-929583-00-0. - Paperback

- Hauge, Michael (1991), Writing Screenplays that Sell, New York: Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-272500-9

- Yves Lavandier (2005). Writing Drama, A Comprehensive Guide for Playwrights and Scritpwriters. Le Clown & l'Enfant. ISBN 2-910606-04-X. - Paperback

- David Trottier (1998). The Screenwriter's Bible: A Complete Guide to Writing, Formatting, and Selling Your Script. Silman-James Press. ISBN 1-879505-44-4. - Paperback

- Vogler, Christopher (2007), The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (3rd ed.), Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, ISBN 978-1-932907-36-0

External links

| Library resources about Screenwriting |

Media related to Screenwriting at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Screenwriting at Wikimedia Commons- Screenwriting at Curlie

- Screenwriters Lectures: Screenwriters on Screenwriting Series at BAFTA

- The Writers Guild of America

- American Screenwriters Association