Scutosaurus

Scutosaurus ("shield lizard") is an extinct genus of pareiasaur parareptiles. Its genus name refers to large plates of armor scattered across its body. It was a large anapsid reptile that, unlike most reptiles, held its legs underneath its body to support its great weight.[2] Fossils have been found in the Sokolki Assemblage Zone of the Malokinelskaya Formation in European Russia, close to the Ural Mountains, dating to the late Permian (Lopingian) between 264 and 252 million years ago.

| Scutosaurus Temporal range: Lopingian ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton at the American Museum of Natural History with an upright posture | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Parareptilia |

| Order: | †Procolophonomorpha |

| Clade: | †Pareiasauria |

| Genus: | †Scutosaurus Hartmann-Weinberg, 1930 |

| Species: | †S. karpinskii |

| Binomial name | |

| †Scutosaurus karpinskii (Amalitskii, 1922) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Research history

The first fossils were uncovered by Russian paleontologist Vladimir Prokhorovich Amalitskii while documenting plant and animal species in the Upper Permian sediments in the Northern Dvina River, Arkhangelsk District, Northern European Russia. Amalitskii had discovered the site in 1899, and he and his wife Anne Amalitskii continued to oversee excavation until 1914, recovering numerous nearly complete and articulated (in their natural position) skeletons belonging to a menagerie of different animals.[3] Official diagnoses of these specimens was delayed due to World War I.[4] The first published name of what is now called Scutosaurus karpinskii was in 1917 by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson, who captioned a reconstruction of its scapulocoracoid[5] based on the poorly preserved specimen PIN 2005/1535[4] "Pariasaurus Karpinskyi, Amalitz" (giving credit to Amalitskii for the name).[5] Amalitskii died later that year, and the actual diagnosis of the animal was posthumously published in 1922, with the name "Pareiosaurus" karpinskii,[3] and the holotype specimen designated as the nearly complete skeleton PIN 2005/1532.[1] Three partial skulls were also found, but Amalitskii decided to split these off into new species as "P. elegans", "P. tuberculatus", and "P. horridus".[3]

"Pariasaurus" and "Pareiosaurus" were both misspellings of the South African Pareiasaurus.[4] In 1930, Soviet vertebrate paleontologist Aleksandra Paulinovna Anna Hartmann-Weinberg said that the pareiasaur material from North Dvina represents only 1 species, and that this species was distinct enough from other Pareiasaurus to justify placing it in a new genus. Though Amalitskii had used a unique genus name "Pareiosaurus", this was an accident, and she declared "Pareiosaurus" to be a junior synonym of Pareiasaurus, and erected the genus Scutosaurus. She used the spelling "karpinskyi" for the species name,[6] but switched to karpinskii in 1937. At the same time, she also split off another unique genus "Proelginia permiana" based on the partial skull PIN 156/2.[7] In 1968, Russian paleontologist N. N. Kalandadze and colleagues considered "Proelginia" to be synonymous with Scutosaurus.[8] Because the remains are not well preserved, the validity of "Proelginia" is unclear. In 1987, Russian paleontologist Mikhail Feodosʹevich Ivakhnenko erected a new species "S. itilensis" based on skull fragments PIN 3919, and resurrected "S. tuberculatus", but Australian biologist Michael S. Y. Lee considered both of these actions unjustified in 2000.[1] In 2001, Lee petitioned the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to formally override the spelling karpinskyi (because Watson clearly did not intend his work to be a formal description of the species, and karpinskii was much more popularly used) and list the author citation as Amalitskii, 1922.[4]

Scutosaurus is a common fossil at the North Dvina site, and is known from 6 at least fairly complete skeletons, as well as numerous various isolated body and skull remains, and scutes (osteoderms). It is the most completely known pareiasaur. All Scutosaurus specimens date to the Upper Tatarian (Vyatskian) Russian faunal stage,[1] which may roughly correspond with the Lopingian epoch of the Upper Permian[9] (259–252 million years ago).[10] In 1996, Russian paleontologist Valeriy K. Golubev described the faunal zones of the site, and listed the Scutosaurus zone as extending from roughly the middle Wuchiapingian to the middle Changhsingian, which followed the "Proelginia" stage beginning in the early Wuchiapingian.[11][12]

Anatomy

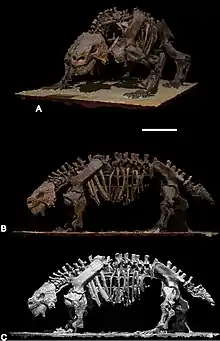

Pareiasaurs were among the largest reptiles during the Permian. Scutosaurus is a rather large pareiasaur, measuring about 2.5–3 m (8 ft 2 in – 9 ft 10 in) in length and weighing up to 1,160 kilograms (2,560 lb).[13] The entire body would have been covered in rough osteoderms, which feature a central boss with a spine. These osteoderms appear to have been largely separate from each other, but may have been closely sutured together over the shoulder and pelvis as in Elginia. The limbs bore small conical studs. Pareiasaurs feature a short stout body, and a short tail. Scutosaurus has 19 presacral vertebrae.[1] Pareiasaurs, as well as many other common herbivorous Permian tetrapods, had a large body, barrel-shaped ribcage, and engorged limbs and pectoral and pelvic girdles.[14] The pareiasaur shoulder blade is large, plate-like, slightly expanded towards the arm, and vertically oriented. The acromion (which connects to the large clavicle) is short and blunt, like those of early turtles, and is placed at the bottom of the shoulder blade. In articulated specimens (where the positions of the jointed bones has been preserved), there is a small gap between the clavicle and the shoulder blade. Early pareiasaurs have a cleithrum which runs along the shoulder blade, but later ones including Scutosaurus lost this.[15] The digits on the hands and feet are short.[16] The dorsal vertebrae are short, tall, and robust, and supported large and strongly curved ribs. The broad torso may have conferred an expansive digestive system.[17]

The cheeks strongly flare out and terminate with long pointed bosses. The bosses of the skull are generally much more prominent than those of other pareiasaurs. The maxilla features a horn just behind the nostrils. The two holes on the back of the palate (the interpterygoid vacuities) are large.[1] All pareiasaurs have broad snouts containing a row of closely packed, tall, blade-like, and heterodont teeth with varying numbers of cusps depending on the tooth and species.[17] Scutosaurus has 18 teeth in the upper jaw (which feature anywhere from 9–11 cusps), and 16 in the lower (13–17 cusps). The tips of the upper teeth jut outward somewhat. The tongue side of the lower teeth bear a triangular ridge, and some random teeth in either jaw can have a cusped cingulum. Unlike other pareiasaurs, Scutosaurus has a small tubercle (a bony projection) on the base of the skull between the basal tubera.[1]

Palaeobiology

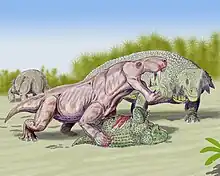

Scutosaurus was a massively built reptile, with bony armor, and a number of spikes decorating its skull.[2] Despite its relatively small size, Scutosaurus was heavy, and its short legs meant that it could not move at speed for long periods of time, which made it vulnerable to attack by large predators. To defend itself Scutosaurus had a thick skeleton covered with powerful muscles, especially in the neck region. Underneath the skin were rows of hard, bony plates (scutes) that acted like a form of brigandine armor.[18]

As a plant-eater living in a semi-arid climate, including deserts, Scutosaurus would have wandered widely for a long time in order to find fresh foliage to eat. It may have stuck closely to the riverbanks and floodplains where plant life would have been more abundant, straying further afield only during times of drought. Its teeth were flattened and could grind away at the leaves and young branches before digesting them at length in its large gut. Scutosaurus swallowed gastroliths to digest plants. Given that it needed to eat constantly, Scutosaurus probably lived alone, or in very small herds, so as to avoid denuding large areas of their edible plants.

Pareiasaurs had long been thought to be terrestrial, but it is difficult to assess their range of locomotion given the lack of modern anatomical analogues. In 1987, Ivakhnenko hypothesised that they were aquatic or amphibious due to the deep and low-lying pectoral girdle, short but engorged limbs, and thick cartilage on the limb joints, which are reminiscent of the aquatic dugong. Subsequent studies—including stable isotope analyses and footprint analyses—on various African and Eurasian remains have all reported results consistent with terrestrial behavior. Caseids have a broadly similar build to pareiasaurs, and possibly exhibited the same locomotory habits. Both have thin, porous long bones which is consistent with modern diving creatures, but the overall heavy torso would impede such a behavior. Nonetheless, similarly graviportal creatures have much thicker long bones. In 2016, zoologist Markus Lambertz and colleagues, based on the thin bones and short neck unsuited for reaching low-lying plants, suggested that caseids were predominantly aquatic and only came ashore during brief intervals. Overall, anatomical evidence seems to be at direct odds with isotopic evidence; it is possible that bone anatomy was more related to the animal's weight than its lifestyle.[19]

Like other pareiasaurs, Scutosaurus have been shown to have had a fast initial growth rate, with cyclical growth intervals. Following this possibly relatively short juvenile period, an individual would have reached 75% of its full size, and continued growing at a slower rate for several years more. This switch from fast to slow growth potentially signaled the onset of sexual maturity.[19]

Paleoecology

Scutosaurus comes from the Salarevskaya Formation, which has a uniformly red coloration and comprises paleosol horizons, which deposit in cyclically shallow-water and dry area. The paleosol horizons are highly variable in shape and size throughout the formation, which may mean they came from different sources (polygenic). Paleosols gradually disappear in the upper part of the formation where the thickness of beds becomes much more discontinuous as well as irregular (from some millimeters to several meters), and the appearance of blue spots which may represent the accumulation of reduced iron oxides. These beds are capped off by a carbonate shell, varying from a small knot to up to a meter (3.3 ft) thick. The paleosols and shells feature holes left behind by plant roots, but these are absent in the clay-siltstone breccias and sand lenses. The formation has typically been explained as the result of several catastrophic floods washing over arid to semi-arid plains during wet seasons, featuring several temporarily filled channels and permanently dry lakes.[20]

Scutosaurus was a member of the pareiasaurian–gorgonopsian fauna dating to the Upper Tatarian, dominated by pareiasaurs, anomodonts, gorgonopsians, therocephalians, and cynodonts. Unlike earlier beds, dinocephalians are completely absent. Scutosaurus is identified in the Sokolki fauna, which features predominantly the former 3 groups. The only herbivore other than Scutosaurus is Vivaxosaurus. Carnivores are instead much more common, the largest identified being Inostrancevia (I. latifrons and I. alexandri); the other gorgonopsians are Pravoslavlevia and Sauroctonus progressus. Other carnivores include the therocephalian Annatherapsidus petri and the cynodont Dvinia; chroniosuchid and seymouriamorph amphibians have also been identified, including Karpinskiosaurus, Kotlassia, and Dvinosaurus.[21] As for plants, the area has yielded various mosses, lepidophytes, ferns, and peltaspermaceaens.[20]

References

- Lee, M. S. Y. (4 December 2003). "The Russian Pariesaurs". The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–84. ISBN 978-0-521-54582-2.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 64. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Amalitskii, V. P. (1922). "Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the Upper Permian on North Dvina" (PDF). Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk. 6 (16): 329–335.

- Lee, M. S. Y. (2001). "Pareiasaurus karpinskii Amalitzky, 1922 (currently Scutosaurus karpinskii, Reptilia, Pareiasauria): proposed conservation of the specific name". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 58 (3): 220–223.

- Watson, D. M. S. (1917). "The evolution of the tetrapod shoulder girdle and fore-limb". Journal of Anatomy. 52 (Pt 1): 10. PMC 1262838. PMID 17103828.

- Hartmann-Weinberg, A. (1930). "Zur Systematik der Nord-Düna-Pareiasauridae" [On the systematics of the North Dvina Pareiasauridae]. Paläontologische Zeitschrift (in German). 12: 47–59. doi:10.1007/BF03045064. S2CID 129354564.

- Hartmann-Weinberg, A. (1937). "Pareiasauriden als Leitfossilien" [Pareiasaurids as guide fossils]. Problemy Paleontologii (in German). 213 (2–3): 649–712.

- Kalandadze, N. N.; Ochev, V. G.; Tatarinov, L. P.; et al. (1968). "Catalogue of the Permian and Triassic tetrapods in the USSR". Upper Paleozoic and Mesozoic Amphibians and Reptiles in the USSR. Nauka.

- Kukhtinov, D. A.; Lozovsky, V. R.; Afonin, S. A.; Voronkova, E. A. (2008). "Non-marine ostracods of the Permian-Triassic transition from sections of the East European platform". Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana. 127 (3): 719.

- "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- Golubev, V. K. "Faunal and floral zones of the Upper Permian: 5.9. Terrestrial vertebrates". Stratotipy i opornye razrezyverkhnei permi Povolzh'ya i Prikam'ya [Stratotypes and Reference Sections of the Upper Permian in the Region of the Volga and Kama Rivers]. Ekotsentr.

- Sennikov, A. G.; Golubev, V. K. (2017). "Sequence of Permian tetrapod faunas of Eastern Europe and the Permian–Triassic ecological crisis". Paleontological Journal. 51 (6): 602. doi:10.1134/S0031030117060077. S2CID 89877840.

- Romano, Marco; Manucci, Fabio; Rubidge, Bruce; Van den Brandt, Marc J. (2021). "Volumetric Body Mass Estimate and in vivo Reconstruction of the Russian Pareiasaur Scutosaurus karpinskii". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 9. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.692035. ISSN 2296-701X.

- Reisz, R. R.; Sues, H.-D. (2000). "Herbivory in late Paleozoic and Triassic terrestrial vertebrates". Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates: Perspectives from the Fossil Record. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–41. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511549717.003. ISBN 9780521594493.

- Lee, M. S. Y. (1996). "The homologies and early evolution of the shoulder girdle in turtles". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 263 (1366): 112. Bibcode:1996RSPSB.263..111L. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0018. S2CID 84529868.

- Gublin, Y. M.; Golubev, V.; Bulanov, V. V.; Petuchov, S. V. (2003). "Pareiasaurian Tracks from the Upper Permian of Eastern Europe" (PDF). Paleontological Journal. 37 (5): 522.

- Reisz, R. R.; Sues, H.-D. (2000). "Herbivory in late Paleozoic and Triassic terrestrial vertebrates". Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates. pp. 23–25. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511549717.003. ISBN 9780521594493.

- Tim Haines; Paul Chambers (2006-07-15). よみがえる恐竜・古生物. Translated by 椿正晴. SB Creative. pp. 46–47. ISBN 4-7973-3547-5.

- Boitsova, E. A.; Skutschas, P. P.; Sennikov, A. G.; et al. (2019). "Bone histology of two pareiasaurs from Russia (Deltavjatia rossica and Scutosaurus karpinskii) with implications for pareiasaurian palaeobiology". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 128 (2): 289–310. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blz094.

- Arefiev, M. P.; Naugolnykh, S. V. (1998). "Fossil Roots from the Upper Tatarian Deposits in the basin of the Sukhona and Malaya Severnaya Dvina Rivers: Stratigraphy, Taxonomy, and Paleoecology". Paleontological Journal. 32 (1): 82–96.

- Modesto, S. P.; Rybczynski, N. (4 December 2003). "The Amniote Faunas of the Russian Permian: Implications for Late Permian Terrestrial Vertebrate Paleogeography". The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–26. ISBN 978-0-521-54582-2.

External links

- Pareiasaurinae at Palaeos