Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 (O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies repulsed the Bulgarian offensive and counterattacked, entering Bulgaria. With Bulgaria's also having previously engaged in territorial disputes with Romania[10] and the bulk of Bulgarian forces engaged in the south, the prospect of an easy victory incited Romanian intervention against Bulgaria. The Ottoman Empire also took advantage of the situation to regain some lost territories from the previous war. When Romanian troops approached the capital Sofia, Bulgaria asked for an armistice, resulting in the Treaty of Bucharest, in which Bulgaria had to cede portions of its First Balkan War gains to Serbia, Greece and Romania. In the Treaty of Constantinople, it lost Adrianople to the Ottomans.

| Second Balkan War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkan Wars | |||||||||

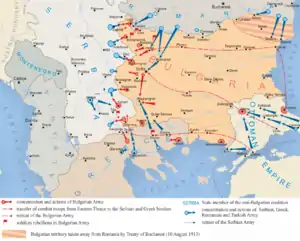

Map of the mainland operations of the Allied belligerents (amphibious actions not shown) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

The political developments and military preparations for the Second Balkan War attracted an estimated 200 to 300 war correspondents from around the world.[11]

Background

During the First Balkan War, which began in October 1912, the Balkan League (Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece) succeeded in driving out the Ottoman Empire from its European provinces (Albania, Macedonia, Sandžak and Thrace), leaving the Ottomans with only East Thrace. The Treaty of London, signed on 30 May 1913, which ended the war, acknowledged the Balkan states' gains west of the Enos–Midia line, drawn from Midia (Kıyıköy) on the Black Sea coast to Enos (Enez) on the Aegean Sea coast, on an uti possidetis basis, and created an independent Albania.

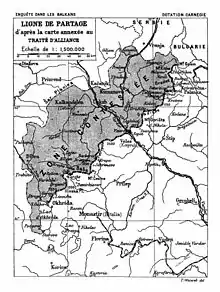

However, the relations between the victorious Balkan allies quickly soured over the division of the spoils, specifically in Macedonia. During the prewar negotiations that resulted in the Balkan League's establishment, a secret agreement on 13 March 1912 was signed by Serbia and Bulgaria, which determined their future boundaries, effectively sharing northern Macedonia. In case of a postwar disagreement, the area to the north of the Kriva Palanka–Ohrid line (with both cities going to the Bulgarians) had been designated as a "disputed zone" under Russian arbitration, with the area to the south of this line assigned to Bulgaria. During the war, the Serbs succeeded in capturing an area far south of the agreed border, down to the Bitola–Gevgelija line (both in Serbian hands). At the same time, the Greeks advanced north, occupying Thessaloniki shortly before the Bulgarians arrived and establishing a common Greek border with Serbia.

When Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support on their Adriatic claims, the Serbs angrily replied that that was a blatant withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion. The Bulgarians insisted that the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement remained active, and the Serbs were still obliged to surrender the area as agreed. The Serbs responded by accusing the Bulgarians of maximalism, pointing out that if they lost both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia, their participation in the common war would have been virtually for nothing.

When Bulgaria called upon Serbia to honour the prewar agreement over northern Macedonia, the Serbs, displeased at the Great Powers' requiring them to give up their gains in north Albania, adamantly refused to evacuate any more territory. The developments ended the Serbo-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable. Soon, minor clashes broke out along the borders of the occupation zones with the Bulgarians against the Serbs and the Greeks. Responding to the perceived Bulgarian threat, Serbia started negotiations with Greece, which also had reasons to be concerned about Bulgarian intentions.

On 19 May/1 June 1913, two days after the signing of the Treaty of London and just 28 days before the Bulgarian attack, Greece and Serbia signed a secret defensive alliance, confirming the current demarcation line between the two occupation zones as their mutual border and concluding an alliance in case of an attack from Bulgaria or from Austria-Hungary. With this agreement, Serbia succeeded in making Greece a part of its dispute over northern Macedonia, since Greece had guaranteed Serbia's current (and disputed) occupation zone in Macedonia.[12] In an attempt to halt the Serbo-Greek rapprochement, Bulgarian Prime Minister Geshov signed a protocol with Greece on 21 May, agreeing on a permanent boundary between their respective forces, effectively accepting Greek control over southern Macedonia. However, his later dismissal ended the diplomatic targeting of Serbia.

Another point of friction arose: Bulgaria's refusal to cede the fortress of Silistra to Romania. When Romania demanded its cession after the First Balkan War, Bulgaria's foreign minister offered instead some minor border changes, which excluded Silistra, and assurances for the rights of the Kutzovlachs in Macedonia. Romania threatened to occupy Bulgarian territory by force, but a Russian proposal for arbitration prevented hostilities. In the resulting Protocol of St. Petersburg of 9 May 1913, Bulgaria agreed to give up Silistra. The resulting agreement was a compromise between the Romanian demands for the city, two triangles at the Bulgaria–Romania border and Balchik and the land between it and Romania and the Bulgarian refusal to accept any cession of its territory. However, the fact that Russia failed to protect the territorial integrity of Bulgaria made the Bulgarians uncertain of the reliability of the expected Russian arbitration of the dispute with Serbia.[13] The Bulgarian behaviour also had a long-term impact on Russo-Bulgarian relations. The uncompromising Bulgarian position to review the prewar agreement with Serbia during a second Russian initiative for arbitration finally led Russia to cancel its alliance with Bulgaria. Both acts made conflict with Romania and Serbia inevitable.

Preparation

Bulgarian war plans

In 1912, Bulgaria's national aspirations, as expressed by Tsar Ferdinand and the military leadership around him, exceeded the provisions of the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano, considered even then as maximalistic, since it included both Eastern and Western Thrace and all Macedonia with Thessaloniki, Edirne and Constantinople.[14] Early evidence of the lack of realistic thinking in Bulgarian leadership[15] was that although Russia had sent clear warnings expressed for the first time on 5 November 1912 (well before the First Battle of Çatalca) that if the Bulgarian army occupied Constantinople they would attack it, they continued their attempts to take the city.

Although the Bulgarian army succeeded in capturing Edirne, Tsar Ferdinand's ambition in crowning himself Emperor in Constantinople also proved unrealistic when the Bulgarian army failed to capture the city in the First Battle of Çatalca. Even worse, the concentration on capturing Thrace and Constantinople ultimately caused the loss of most of Macedonia, including Thessaloniki, and that could not be accepted, leading the Bulgarian military leadership around Tsar Ferdinand to decide upon a war against its former allies. However, with the Ottomans unwilling to accept the loss of Thrace in the east, and an enraged Romania (in the north), the decision to open war against both Greece (to the south) and Serbia (to the west) was a rather adventurous one, since in May the Ottoman Empire had urgently requested a German mission to reorganize the Ottoman army. By mid-June, Bulgaria became aware of the agreement between Serbia and Greece in case of a Bulgarian attack. On 27 June, Montenegro announced that it would side with Serbia in the event of a Serbian-Bulgarian war. On 5 February, Romania settled her differences over Transylvania with Austria-Hungary, signing a military alliance, and on 28 June, officially warned Bulgaria that it would not remain neutral in a new Balkan war.[12]

As skirmishing continued in Macedonia, mainly between Serbian and Bulgarian troops, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia tried to stop the upcoming conflict since Russia did not wish to lose either of its Slavic allies in the Balkans. On 8 June, he sent an identical personal message to the Kings of Bulgaria and Serbia, offering to act as arbitrator according to the provisions of the 1912 Serbo-Bulgarian treaty. Serbia was asking for a revision of the original treaty since it had already lost north Albania due to the Great Powers' decision to establish the state of Albania, which had been recognized as Serbian territory under the prewar Serbo-Bulgarian treaty, in exchange for Bulgarian expansion in northern Macedonia. The Bulgarian reply to the Russian invitation contained so many conditions that it amounted to an ultimatum, leading Russian diplomats to realize that the Bulgarians had already decided to go to war with Serbia. That caused Russia to cancel the arbitration initiative and angrily repudiate its 1902 treaty of alliance with Bulgaria. Bulgaria was shattering the Balkan League, Russia's best defence against Austrian–Hungarian expansionism, a structure that had cost Russia much blood, money and diplomatic capital during the last 35 years.[16] Russia's Foreign Minister Sazonov's exact words to Bulgaria's new Prime Minister Stoyan Danev were "Do not expect anything from us, and forget the existence of any of our agreements from 1902 until the present."[17] Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was already angry with Bulgaria because the latter refused to honour its recently signed agreement with Romania over Silistra, which resulted from Russian arbitration. Then Serbia and Greece proposed that each of the three countries reduce its army by one-fourth as a first step to facilitate a peaceful solution, but Bulgaria rejected it.

Bulgaria was already on the track to war since a new cabinet had been formed in Bulgaria where the pacifist Geshov was replaced by the hardliner and head of a Russophile party, Dr. Danev, as premier. There is some evidence that to overcome Tsar Ferdinand's reservations over a new war against Serbia and Greece, certain personalities in Sofia threatened to overthrow him. In any case, on 16 June, the Bulgarian high command, under the direct control of Tsar Ferdinand and without notifying the government, ordered Bulgarian troops to start a surprise attack simultaneously against both the Serbian and Greek positions without declaring war and to dismiss any orders contradicting the attack order. The next day the government pressured the General Staff to order the army to cease hostilities, which caused confusion and loss of initiative and failed to remedy the state of undeclared war. In response to the government pressure, Tsar Ferdinand dismissed General Savov and replaced him with General Dimitriev as commander-in-chief.

Bulgaria intended to defeat the Serbs and Greeks and to occupy areas as large as possible before the Great Powers interfered to end the hostilities. To provide the necessary superiority in arms, the entire Bulgarian army was committed to these operations. No provisions were made in case of an (officially declared) Romanian intervention or an Ottoman counterattack, strangely assuming that Russia would assure that no attack would come from those directions,[18] even though on 9 June Russia had angrily repudiated its Bulgarian alliance and shifted its diplomacy towards Romania (Russia already had named Romania's King Carol an honorary Russian field marshal, as a clear warning in changing its policy towards Sofia in December 1912).[12] The plan was for a concentrated attack against the Serbian army across the Vardar plain to neutralize it and to capture northern Macedonia, together with a less concentrated one against the Greek military near Thessaloniki, which had approximately half the size of the Serbian army, to capture the city and south Macedonia. The Bulgarian high command was not sure whether their forces were enough to defeat the Greek army but believed them to be enough for defending the south front as a worst-case scenario until the arrival of reinforcements after defeating the Serbs to the north.

Opposing forces

According to the Military Law of 1903, the armed forces of Bulgaria were divided into two categories: the Active Army and the National Militia. The core of the Armed forces consisted of nine infantry and one cavalry division. The Bulgarian army had a unique organization among those of Europe since each infantry division had three brigades of two regiments, composed of four battalions of six heavy companies of 250 men each, plus an independent battalion, two large artillery regiments and one cavalry regiment, giving a total of 25 very heavy infantry battalions and 16 cavalry companies per division,[19] which was more than the equivalent of two nine-battalion divisions, the standard divisional structure in most armies, as was also the case with the Greek and Serbian militaries in 1913. Consequently, although the Bulgarian army had 599,878 men[20][21] mobilized at the beginning of the First Balkan War, there were only nine organizational divisions, giving a divisional strength closer to an Army Corps than to a Division. Tactical necessities during and after the First Balkan War modified this original structure: a new 10th division was formed using two brigades from the 1st and 6th divisions, and an additional three independent brigades were formed from recruits. Nevertheless, the heavy structure generally remained. By contrast, the Greek Army of Macedonia also had nine divisions, but the total number of men under arms was only 118,000. Another decisive factor affecting the real strength of the divisions between the opposing armies was the distribution of artillery. The nine-division-strong Greek Army had 176 guns, and the ten-division-strong Serbian army had 230. The Bulgarians had 1,116, a ratio of 6:1 against the Greeks and 5:1 against the Serbian army.

There is a dispute over the strength of the Bulgarian army during the Second Balkan War. At the outbreak of the First Balkan War, Bulgaria mobilized a total of 599,878 men (366,209 in the Active Army; 53,927 in the supplementing units; 53,983 in the National Militia; 94,526 from the 1912 and 1913 levies; 14,204 volunteers; 14,424 in the border guards). The non-recoverable casualties during the First Balkan War were 33,000 men (14,000 killed and 19,000 died of disease). To replace these casualties, Bulgaria conscripted 60,000 men between the two wars, mainly from the newly occupied areas, using 21,000 of them to form the Seres, Drama and Odrin (Edirne) independent brigades. It is known that there were no demobilized men. According to the Bulgarian command, the army had 7,693 officers and 492,528 soldiers in its ranks on 16 June (including the three brigades mentioned above).[22] This gives a difference of 99,657 men in strength between the two wars. In comparison, subtracting the actual number of casualties, including wounded and adding the newly conscripted men produces no less than 576,878 men. The army was experiencing shortages of war materials and had only 378,998 rifles at its disposal.

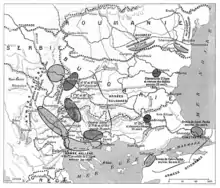

The 1st and 3rd armies (under generals Vasil Kutinchev and Radko Dimitriev respectively) were deployed along the old Serbian-Bulgarian borders, with the 5th Army under general Stefan Toshev around Kyustendil, and the 4th Army under General Stiliyan Kovachev in the Kočani–Radoviš area. The 2nd Army under general Nikola Ivanov was detailed against the Greek army.

The army of the Kingdom of Serbia accounted for 348,000 men (out of which 252,000 were combatants)[2] divided into three armies with ten divisions. Its main force was deployed on the Macedonian front along the Vardar River and near Skopje. Its nominal commander-in-chief was King Peter I, with Radomir Putnik as his chief of staff and effective field commander.

By early June, the army of the Kingdom of Greece had some 142,000 armed men with nine infantry divisions and one cavalry brigade. The bulk of the army with eight divisions and a cavalry brigade (117,861 men) was gathered in Macedonia, positioned in an arc covering Thessaloniki to the north and northeast of the city, while one division and independent units (24,416 men) were left in Epirus. With the eruption of hostilities, the 8th Infantry Division (stationed in Epirus) was transferred to the front, and with the arrival of recruits, the army's strength in the Macedonian theatre increased eventually to some 145,000 men with 176 guns. King Constantine I assumed command of the Greek forces, with Lt. General Viktor Dousmanis as his chief of staff.

The Kingdom of Montenegro sent one division of 12,000 men under General Janko Vukotić to the Macedonian front.

The Kingdom of Romania had the largest army in the Balkans, although it had not seen action since the Romanian War of Independence against the Ottomans in 1878. Its peacetime strength was 6,149 officers and 94,170 men, and it was well equipped by Balkan standards, possessing 126 field batteries, fifteen howitzer and three mountain batteries made primarily by Krupp. Upon mobilizing, the Romanian army mustered 417,720 men allocated to five army corps. Some 80,000 were assembled to occupy the Southern Dobruja, while an army of 250,000 was assembled to carry the main offensive into Bulgaria.[2]

Start of the war

The primary Bulgarian attack was planned against the Serbs with their 1st, 3rd, 4th and 5th Armies, while the 2nd army was tasked with an attack toward Greek positions around Thessaloniki. However, in the crucial opening days of the war, only the 4th Army and 2nd Army were ordered to advance. This allowed the Serbs to concentrate their forces against the attacking Bulgarians and hold their advance. The Bulgarians were outnumbered on the Greek front, and the low-level fighting soon turned into a Greek attack all along the line on 19 June. The Bulgarian forces were forced to withdraw from their positions north of Thessaloniki (except the isolated battalion stationed in the city itself, which was quickly overrun) to defensive positions between Kilkis and Struma river. The plan to rapidly destroy the Serbian army in central Macedonia by concentrated attack turned out to be unrealistic, with the Bulgarian army starting to retreat even before Romanian intervention, and the Greek advance necessitated the disengagement of forces to defend Sofia.

Bulgarian offensive against Greece

The Bulgarian 2nd army in southern Macedonia, commanded by General Ivanov, held a line from Dojran Lake southeast to Kilkis, Lachanas, Serres and then across the Pangaion Hills to the Aegean Sea. The army had been in place since May and was considered a veteran force, having fought at the siege of Edirne in the First Balkan War. Though General Ivanov, possibly to avoid any responsibility for his crushing defeat, claimed after the war that his army consisted of only 36,000 men and that many of his units were weakened, a detailed analysis concerning his units contradicted him. Ivanov's 2nd army consisted of the 3rd division minus one brigade with four regiments of four battalions (a total of 16 battalions plus the divisional artillery), the I/X brigade with the 16th and 25th regiments (total of eight battalions plus artillery), the Drama Brigade with the 69th, 75th and 7th regiments (total of 12 battalions), the Seres Brigade with 67th and 68th regiments (total of 8 battalions), the 11th division with the 55th, 56th and 57th regiments (total of 12 battalions plus the divisional artillery), the 5th Border Battalion, the 10th Independent Battalion and the 10th Cavalry Regiment of seven mounted and seven infantry companies. In total, Ivanov's force comprised 232 companies in 58 infantry battalions, a cavalry regiment (14 companies) with 175 artillery guns, numbering between 80,000 (official Bulgarian source) and 108,000 (official Greek source according to the official Bulgarian history of the war before 1932).[23] All modern historians agree that Ivanov underestimated the number of his soldiers, but the Greek army still had a numerical superiority.[2] The Greek Headquarters also estimated the numbers of their opponents from 80,000 to 105,000 men.[24] A large part of Ivanov's forces, and especially the Drama Brigade and the Seres Brigade, were composed of completely untrained local recruits.[24]

The Greek army, commanded by King Constantine I, had eight divisions and a cavalry brigade (117,861 men) with 176 artillery guns[25] in a line extending from the Gulf of Orphanos to the Gevgelija area. Since the Greek headquarters did not know where the Bulgarian attack would occur, the Bulgarians would have temporary local superiority in the location chosen for the attack.

On 26 June, the Bulgarian army received orders to destroy the opposing Greek forces and to advance towards Thessaloniki. The Greeks stopped them, and by 29 June, an order for a general counterattack was issued. At Kilkis, the Bulgarians had constructed strong defences, including captured Ottoman guns which dominated the plain below. The Greek 4th, 2nd, and 5th divisions attacked across the plain in rushes supported by artillery. The Greek Army suffered heavy casualties but carried the trenches by the next day. On the Bulgarian left, the Greek 7th Division captured Serres and the 1st and 6th divisions captured Lachanas. The defeat of the 2nd army by the Greeks was the most serious military disaster suffered by the Bulgarians in the Second Balkan War. Bulgarian sources give 6,971 casualties, over 6,000 prisoners, and over 130 artillery pieces captured by the Greeks, who suffered 8,700 casualties.[26] On 28 June, the retreating Bulgarian army and irregulars burned down the major city of Serres (a predominantly Greek town surrounded by both Bulgarian – to the north and west – and Greek – to the east and south – villages[27]), and the towns of Nigrita, Doxato and Demir Hisar,[28] ostensibly as a retaliation for the burning of the Bulgarian town of Kilkis by the Greeks, which had taken place after the named battle, as well as the destruction of many Bulgarian villages in the region.[29] On the Bulgarian right, Greek Evzones captured Gevgelija and the heights of Matsikovo. Consequentially, the Bulgarian line of retreat through Dojran was threatened, and Ivanov's army began a desperate retreat, threatening at times to become a rout. Reinforcements from the 14th division came too late, joining the retreat towards Strumica and the Bulgarian border. The Greeks captured Dojran on 5 July but were unable to cut off the Bulgarian retreat through Struma Pass. On 11 July, the Greeks came in contact with the Serbs and then pushed up the Struma River. Meanwhile, the Greek forces, with the support of their navy, landed in Kavala and then penetrated inland to western Thrace. On 19 July, the Greeks captured Nevrokop, and on 25 July, in another amphibious operation, entered Dedeagac (today Alexandroupoli), thus cutting off the Bulgarians completely from the Aegean sea.[30]

Serbian front

The 4th Bulgarian army held the most important position in the attempted conquest of Serbian Macedonia.[31] The fighting began on 29–30 June 1913, between the 4th Bulgarian army and the 1st and 3rd Serbian armies, first along the Zletovska and then after a Bulgarian retreat, along the Bregalnica.[31] Internal confusion led to heavy Bulgarian losses in 1–3 July.[31] The Serbs captured the whole 7th Division of the 4th Bulgarian Army, without any fight.[31] By 8 July, the Bulgarian army had been severely defeated.[32]

On the north, the Bulgarians started to advance towards the Serbian border town of Pirot and forced Serbian Command to send reinforcements to the 2nd army defending Pirot and Niš. This enabled Bulgarians to stop the Serbian offensive in Macedonia at Kalimanci on 18 July.

On 13 July 1913, General Mihail Savov assumed control of the 4th and 5th Bulgarian armies.[33] The Bulgarians dug into strong positions around the village of Kalimantsi, at the Bregalnica river in the northeastern Macedonia region.[33] On 18 July, the Serbian 3rd army attacked, closing in on Bulgarian positions.[33] The Bulgarians held firm, and the artillery successfully broke up the Serb attacks.[33] If the Serbs had broken through the Bulgarian defences, they might have doomed the 2nd Bulgarian Army and driven the Bulgarians entirely out of Macedonia.[33] The defensive victory, along with the successes to the north of the 1st and 3rd armies, protected western Bulgaria from a Serbian invasion.[34] Although this boosted the Bulgarians, the situation was critical in the south, with the Greek Army.[34]

Greek offensive

The Serbian front had become static. Seeing that the Bulgarian Army in front of him had already been defeated, King Constantine ordered the Greek Army to march further into Bulgarian territory and take the capital city of Sofia. Constantine wanted a decisive victory despite objections by his Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos, who realized that the Serbs, having won their territorial objectives, now adopted a passive stance and shifted the weight of carrying the rest of the war to the Greeks. In the pass of Kresna (Battle of Kresna Gorge), the Greeks were ambushed by the Bulgarian 2nd and 4th armies, which had newly arrived from the Serbian front and had taken defensive positions there. By 21 July, the Greek army was outnumbered by the now counterattacking Bulgarians, and the Bulgarian General Staff, attempting to encircle the Greeks in a Cannae-type battle, was applying pressure on their flanks.[34] However, after bitter fighting, the Greek side managed to break through the Kresna pass and captured Simitli on 26 July,[35] while at the night of 27–28 July, the Bulgarian forces were pushed north to Gorna Dzhumaya (Blagoevgrad), 76 km south of Sofia.[36] Meanwhile, the Greek forces continued their march inland into western Thrace, on 26 July, they entered Xanthi and the next day Komotini.[36] On 28 July, the Bulgarian army, under heavy pressure, was forced to abandon Gorna Dzhumaya.[37]

The Greek army was exhausted and faced logistical difficulties, but resisted strenuously and launched local counterattacks. By 30 July, the Bulgarian army downscaled its attacks, having to repulse Greek counterattacks on both sides. On the eastern flank, the Greek army launched a counterattack towards Mehomia through the Predela pass. The offensive was stopped by the Bulgarians on the eastern side of the pass and fighting ground to a stalemate. On the western flank, an offensive was launched against Tsarevo Selo to reach the Serbian lines. This failed, and the Bulgarian army continued advancing, especially in the south. However, after three days of fighting at the sectors of Pehchevo and Mahomia, the Greek forces retained their positions.[38]

Romanian intervention

Romania mobilized its army on 5 July 1913, intending to seize Southern Dobruja, and declared war on Bulgaria on 10 July.[2] In a diplomatic circular that said, "Romania does not intend either to subjugate the polity nor defeat the army of Bulgaria," the Romanian government endeavoured to allay international concerns about its motives and about increased bloodshed.[2] According to Richard Hall, "[t]he entrance of Romania into the conflict made the Bulgarian situation untenable [and t]he Romanian thrust across the Danube was the decisive military act of the Second Balkan War."[39]

On the day of Romania's declaration, 80,000 men of the 5th Corps under General Ioan Culcer invaded Dobruja, occupying a front from Tutrakan to Balchik.[2] The corps cavalry occupied the port city of Varna until it was clear that there would be no Bulgarian resistance.[2] On the night of 14–15 July, the Danube Army under Prince Ferdinand crossed into Bulgaria at Oryahovo, Gigen and Nikopol.[2] The initial occupation completed, Romanian forces were divided into two groups: one advanced westward, towards Ferdinand (now Montana), and the other advanced southwestward, towards Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, everywhere preceded by a wide fan of cavalry troops in reconnaissance.[40]

On 18 July, Romania took Ferdinand, and on 20 July, they occupied Vratsa, 116 km north of Sofia. On 23 July, advanced cavalry forces had entered Vrazhdebna, a suburb only 7 miles (11 km) from Sofia.[40] The Romanians and Serbs linked up at Belogradchik on 25 July, isolating the important city of Vidin. The Bulgarian rear was entirely exposed, no resistance had been offered, the capital was open to the invader, and the country's northwestern corner was cut off and surrounded.[40] During the invasion, the fledgling Romanian Air Corps performed photoreconnaissance and propaganda leaflet drops. Sofia became the first capital city in the world to be overflown by enemy aircraft.[40]

Romania did not count any combat casualties during its brief war. Its forces were struck by an outbreak of cholera, which cut down 1,600 men.[5][6][7]

Ottoman intervention

The lack of resistance to the Romanian invasion convinced the Ottomans to invade the territories just ceded to Bulgaria. The main object of the invasion was the recovery of Edirne (Adrianople), which was held by Major General Vulko Velchev with a mere 4,000 troops.[9] Most Bulgarian forces occupying East Thrace had been withdrawn to face the Serbo-Greek attack earlier in the year. On 12 July, Ottoman troops garrisoning Çatalca and Gelibolu reached the Enos–Midia line and on 20 July 1913 crossed the line and invaded Bulgaria.[9] The entire Ottoman invasion force contained between 200,000 and 250,000 men under the command of Ahmed Izzet Pasha. The 1st Army was stationed at the eastern (Midia) end of the line. From east to west it was followed by the 2nd Army, 3rd Army and 4th Army, which was stationed at Gelibolu.[9]

In the face of the advancing Ottomans, the outnumbered Bulgarian forces retreated to the prewar border. Edirne was abandoned on 19 July, but, since the Ottomans did not occupy it immediately, the Bulgarians re-occupied it the next day (20 July). Since it was apparent that the Ottomans were not stopping, it was abandoned a second time on 21 July and occupied by the Ottomans on 23 July.[9] Edirne had been conquered by Sultan Murad I in the 1360s and had served as the first European capital of the Empire before the capture of Constantinople in 1453. Minister of War Enver Pasha called himself the "Second Conqueror of Edirne," although the conquering forces had met no resistance on the way to Edirne.[9]

The Ottoman armies did not stop at the old border but crossed into Bulgarian territory. A cavalry unit advanced on Yambol and captured it on 25 July.[9] The Ottoman invasion, more than the Romanian, incited panic among the peasantry, many of whom fled to the mountains. Among the leadership, it was recognized as a complete reversal of fortune. In the words of historian Richard Hall, "[t]he battlefields of eastern Thrace, where so many Bulgarian soldiers had died to win the First Balkan War, were again under Ottoman control."[9] Like the Romanians, the Ottomans suffered no combat casualties but lost 4,000 soldiers to cholera.[9] Some 8000 Armenians fighting for the Ottomans were wounded. The sacrifice of these Armenians was praised greatly in Turkish papers.[41]

To help Bulgaria repulse the rapid Ottoman advance in Thrace, Russia threatened to attack the Ottoman Empire through the Caucasus and send its Black Sea Fleet to Constantinople; this caused Britain to intervene.

According to the 1918 book Destruction of the Thracian Bulgarians in 1913, Ottoman forces perpetrated atrocities against the Bulgarians in Eastern Thrace during the invasion and aftermath.

Negotiating a way out

Armistice

As the Romanian army closed in on Sofia, Bulgaria asked Russia to mediate. On 13 July, Prime Minister Stoyan Danev resigned in the face of Russian inactivity. On 17 July, the tsar appointed Vasil Radoslavov to head a pro-German and Russophobic government.[33] On 20 July, via Saint Petersburg, the Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić invited a Bulgarian delegation to treat with the allies directly at Niš in Serbia. The Serbs and Greeks, both now on the offensive, were in no rush to conclude a peace. On 22 July, Tsar Ferdinand sent a message to King Carol via the Italian ambassador in Bucharest. The Romanian armies halted before Sofia.[33] Romania proposed that talks be moved to Bucharest, and the delegations took a train from Niš to Bucharest on 24 July.[33]

When the delegations met in Bucharest on 30 July, the Serbs were led by Pašić, the Montenegrins by Vukotić, the Greeks by Venizelos, the Romanians by Titu Maiorescu and the Bulgarians by Finance Minister Dimitur Tonchev. They agreed to a five-day armistice to come into effect on 31 July.[42] Romania refused to allow the Ottomans to participate, forcing Bulgaria to negotiate with them separately.[42]

Treaty of Bucharest

Bulgaria had agreed to cede Southern Dobruja to Romania as early as 19 July. At the peace talks in Bucharest, the Romanians, having obtained their primary objective, were a voice for moderation.[42] The Bulgarians hoped to keep the Vardar River as the boundary between their share of Macedonia and Serbia's. The latter preferred to retain all of Macedonia as far as the Struma. Austro-Hungarian and Russian pressure forced Serbia to be satisfied with most of northern Macedonia, conceding only the town of Štip to the Bulgarians, in Pašić's words, "in honour of General Fichev," who had brought Bulgarian arms to the door of Constantinople in the first war.[42] Ivan Fichev was chief of the Bulgarian general staff and a member of the delegation in Bucharest at the time. When Fichev explained why Bulgaria deserved Kavala, a port on the Aegean occupied by the Greeks, Venizelos is said to have responded, "General, we are not responsible. Before [29] June, we were afraid of you and offered you Serres and Drama and Kavala, but now when we see you, we assume the role of victors and will take care of our interests only."[42] Although Austria-Hungary and Russia supported Bulgaria, the influential alliance of Germany—whose Kaiser Wilhelm II was brother-in-law to the Greek king—and France secured Kavala for Greece. Bulgaria retained the underdeveloped port of Dedeagac (Alexandroupoli).[42]

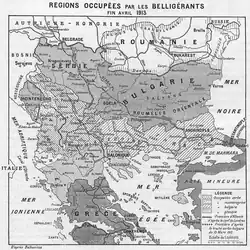

The last day of negotiations was 8 August. On 10 August, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, Romania, and Serbia signed the Treaty of Bucharest and divided Macedonia in three: Vardar Macedonia went to Serbia; the smallest part, Pirin Macedonia, to Bulgaria; and the coastal and largest part, Aegean Macedonia, to Greece.[42] Bulgaria thus enlarged its territory by 16 percent compared to what it was before the First Balkan War, increasing its population from 4.3 to 4.7 million people. Romania enlarged its territory by 5 percent and Montenegro by 62 percent.[43] Greece increased her population from 2.7 to 4.4 million and her territory by 68 percent. Serbia almost doubled her territory, enlarging her population from 2.9 to 4.5 million.[44]

The Montenegrins at Bucharest were primarily interested in obtaining a favourable concession from Serbia in the former Sanjak of Novi Pazar. They did it, later confirming it in a treaty signed at Belgrade on 7 November.[42]

Ottoman treaties

In August, Ottoman forces established a provisional government of Western Thrace at Komotini to pressure Bulgaria to make peace. Bulgaria sent a three-member delegation—General Mihail Savov and the diplomats Andrei Toshev and Grigor Nachovich—to Constantinople to negotiate peace on 6 September.[45] The Ottoman delegation was led by Foreign Minister Mehmed Talat Bey, assisted by future Naval Minister Çürüksulu Mahmud Pasha and Halil Bey. Although Russia tried to intervene throughout August to prevent Edirne from becoming Turkish again, Toshev told the Ottomans at Constantinople that "[t]he Russians consider Constantinople their natural inheritance. Their main concern is that when Constantinople falls into their hands it shall have the largest possible hinterland. If Adrianople is in the possession of the Turks, they shall get it too."[45]

Resigned to losing Edirne, the Bulgarians played for Kırk Kilise (Lozengrad in Bulgarian). Both sides made competing declarations: Savov that "Bulgaria, who defeated the Turks on all fronts, cannot end this glorious campaign with the signing of an agreement which retains none of the battlefields on which so much Bulgarian blood has been shed," and Mahmud Pasha that "[w]hat we have taken is ours."[45] In the end, none of the battlefields were retained in the Treaty of Constantinople of 30 September. In October, Bulgarian forces finally returned south of the Rhodopes. [45] The Radoslavov government continued negotiating with the Ottomans in the hopes of forming an alliance. These talks finally bore fruit in the Secret Bulgarian–Ottoman Treaty of August 1914.

As part of the Treaty of Constantinople, 46,764 Orthodox Bulgarians from Ottoman Thrace were exchanged for 48,570 Muslims (Turks, Pomaks, and Roma) from Bulgarian Thrace.[46] After the exchange, according to the 1914 Ottoman census, there remained 14,908 Bulgarians belonging to the Bulgarian Exarchate in Ottoman Empire.[47]

On 14 November 1913, Greece and the Ottomans signed a treaty in Athens, formally ending their hostilities. On 14 March 1914, Serbia signed a treaty in Constantinople, restoring relations with the Ottoman Empire and reaffirming the 1913 Treaty of London.[45] No treaty between Montenegro and the Ottoman Empire was ever signed.

Aftermath

The Second Balkan War made Serbia the most militarily powerful state south of the Danube.[48] Years of military investment financed by French loans borne fruit. Central Vardar and the eastern half of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar were acquired. Its territory grew in extent from 18,650 to 33,891 square miles, and its population grew by more than one and a half million. The aftermath brought harassment and oppression for many in the newly conquered lands. The freedom of association, assembly and the press guaranteed under the Serbian constitution of 1903 was not introduced into the new territories. The inhabitants were denied voting rights, ostensibly because the cultural level was considered too low, in reality, to keep the non-Serbs, who made up the majority in many areas, out of national politics. Opposition newspapers like Radicke Novine remarked that the 'new Serbs' had better political rights under the Turks.[49] There was a destruction of Turkish buildings, schools, baths, mosques. In October and November 1913, British vice-consuls reported systematic intimidation, arbitrary detentions, beatings, rapes, village burnings and massacres by Serbs in the annexed areas. The Serbian government showed no interest in preventing further outrages or investigating those that had happened. When the Carnegie Commission, composed of an international team of experts selected for their impartiality, arrived in the Balkans, they received virtually no assistance from Belgrade.[50]

The treaties forced the Greek Army to evacuate Western Thrace and Pirin Macedonia, which it had occupied during operations. The retreat from the areas that had to be ceded to Bulgaria, together with the loss of Northern Epirus to Albania, was not well received in Greece; from the areas occupied during the war, Greece succeeded in gaining only the territories of Serres and Kavala after diplomatic support from Germany. Serbia made additional gains in northern Macedonia and, having fulfilled its aspirations to the south, turned its attention to the north where its rivalry with Austro-Hungary over Bosnia-Herzegovina led the two countries to war a year later igniting the First World War. Italy used the excuse of the Balkan wars to keep the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean, which it had occupied during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911 over Libya, despite the agreement that ended that war in 1912.

At the strong insistence of Austria-Hungary and Italy, both hoping to control for themselves the state and thus the Otranto Straits in Adriatic, Albania acquired officially its independence according to the terms of the Treaty of London. With the delineation of the exact boundaries of the new state under the Protocol of Florence (17 December 1913), the Serbs lost their outlet to the Adriatic and the Greeks in the region of Northern Epirus (Southern Albania). This was highly unpopular with the local Greek population, who, after a revolt, managed to acquire local autonomy under the terms of the Protocol of Corfu.[51]

After its defeat, Bulgaria became a revanchist local power looking for a second opportunity to fulfill its national aspirations. After Bucharest, the head of the Bulgarian delegation, Tonchev, remarked that "[e]ither the Powers will change [the territorial settlement], or we will destroy it."[48] To this end, it participated in the First World War on the side of the Central Powers since its Balkan enemies (Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, and Romania) were pro-Entente (see articles on the Serbian Campaign and the Macedonian front of World War I). The resulting enormous sacrifices during World War I and renewed defeat caused Bulgaria a national trauma and new territorial losses.

List of battles

Bulgarian–Greek battles

| Battle | Date | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kilkis-Lahanas | 19–21 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Doiran | 23 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Demir Hisar | 26–27 June 1913 | Nikola Ivanov | Constantine I | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Kresna Gorge | 27–31 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Constantine I | Stalemate |

Bulgarian–Serbian battles

| Battle | Date | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Bregalnica | 30 June–9 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Radomir Putnik | Serbian victory |

| Battle of Knjaževac | 4–7 July 1913 | Vasil Kutinchev | Vukoman Aračić | Bulgarian victory |

| Battle of Pirot | 6–8 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | Serbian victory |

| Battle of Belogradchik | 8 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | Serbian victory |

| Siege of Vidin | 12–18 July 1913 | Krastyu Marinov | Vukoman Aračić | Peace treaty |

| Battle of Kalimanci | 18–19 July 1913 | Mihail Savov | Božidar Janković | Bulgarian victory |

Bulgarian–Ottoman battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Mihail Savov | Enver Pasha | First Armistice |

| Ottoman Advance of Thrace | 1913 | Vulko Velchev | Ahmed Pasha | Final Armistice |

Bulgarian–Romanian battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanian landings in Bulgaria | 1913 | Ferdinand I | Carol I of Romania | First Armistice |

| Southern Dobruja Offensive | 1913 | Ferdinand I | Carol I of Romania | Final Armistice |

References

- "Bulgarian troops loses during the Balkan Wars". Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Hall 2000, p. 117

- Erickson 2003, p. 323.

- Hall 2000, p. 135

- Leașu, Florin; Nemeț, Codruța; Borzan, Cristina; Rogozea, Liliana (2015). "A novel method to combat the cholera epidemic among the Romanian Army during the Balkan War – 1913". Acta medico-historica Adriatica. 13 (1): 159–170. PMID 26203545.

- Ciupală, Alin (25 May 2020). "Epidemiile în istorie | O epidemie uitată. Holera, România și al Doilea Război Balcanic din 1913" (in Romanian). University of Bucharest.

- Stoica, Vasile Leontin (2012). Serviciul Sanitar al Armatei Române în perioada 1914–1919 (PDF) (Thesis) (in Romanian). Chișinău: Ion Creangă State Pedagogical University. pp. 1–196.

- Calculation (PDF) (in Greek), Hellenic Army General Staff, p. 12, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Hall 2000, p. 119

- Iordachi, Constantin (2017). "Diplomacy and the Making of a Geopolitical Question: The Romanian-Bulgarian Conflict over Dobrudja, 1878–1947". Entangled Histories of the Balkans. Vol. 4. Brill. pp. 291–393. ISBN 978-90-04-33781-7. p. 336:

the adjustment of the common frontier in Dobrudja had dominated diplomatic relations between Romania and Bulgaria ever since the aftermath of the Congress of Berlin (1878).

- "Correspondants de guerre", Le Petit Journal Illustré (Paris), 3 novembre 1912.

- "Balkan crises". Texas.net. Archived from the original on 7 November 2009.

- Hall 2000, p. 97

- Penchev, Boyko (2007). Tsarigrade/Istanbul and the Spatial Construction of Bulgarian National Identity in the Nineteenth Century. CAS Sofia Working Paper Series. Central and Eastern European Online Library. pp. 1–18. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017.

- Seton-Watson, R. W. (2009) [1917]. The Rise of Nationality in the Balkans. Charleston, SC: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-113-88264-6.

- Crampton, Richard (1987). A short history of modern Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-27323-7.

- Hall 2000, p. 104

- Hall 2000, p. 108

- Erickson 2003, p. 68

- Hall 2000, p. 24

- The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912–1913, vol. I, Ministry of War, 1937, p. 566

- The war between Bulgaria and Balkan Countries, vol. I, Ministry of War, 1932, p. 158

- The Greek Army during the Balkan Wars, vol. III, Ministry of Army, 1932, p. 97.

- Hall 2000, p. 112

- The Greek Army during the Balkan Wars, vol. C, Ministry of Army, 1932, p. 116.

- Hall 2000, p. 113

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan war (1914), p. 83 "The villages around it are Bulgarian to the north and west, but a rural Greek population approaches it from the south and east" Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Price, W.H. Crawfurd (2008). The Balkan Cockpit – The Political and Military Story of the Balkan Wars in Macedonia. Read Books. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-4437-7404-8.

- Downes, Alexander B. (2008). Targeting Civilians in War. Cornell University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8014-4634-4.

- Hall 2000, p. 115.

- Hall 2000, p. 110

- Hall 2000, p. 111

- Hall 2000, p. 120

- Hall 2000, p. 121

- Gedeon 1998, p. 259.

- Gedeon 1998, p. 260

- Price, Crawfurd (1914). The Balkan cockpit. T. Werner Laurie LTD, p. 336

- Gedeon 1998, p. 261.

- Hall 2000, pp. 117–118.

- Hall 2000, p. 118

- Dennis, Brad (3 July 2019). "Armenians and the Cleansing of Muslims 1878–1915: Influences from the Balkans". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 39 (3): 411–431. doi:10.1080/13602004.2019.1654186. ISSN 1360-2004. S2CID 202282745.

- Hall 2000, pp. 123–124

- "Turkey in the First World War – Balkan Wars". Turkeyswar.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Grenville, John (2001). The major international treaties of the twentieth century. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-415-14125-3.

- Hall 2000, pp. 125–126

- Önder, Selahattin (6 August 2018). "Balkan devletleriyle Türkiye arasındaki nüfus mübadeleleri (1912–1930)" (in Turkish): 27–29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kemal Karpat (1985), Ottoman Population, 1830–1914, Demographic and Social Characteristics, The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 168–169

- Hall 2000, p. 125

- Carnegie report, The Serbian Army during the Second Balkan War, "ECommons@Cornell: Carnegie Report, the Serbian army during the Second Balkan War, 1913". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015., The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark, pp. 42–45

- Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers, p. 45

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6171-0.

Sources

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-97888-5.

- Gerolymatos, André (2002). The Balkan wars: conquest, revolution, and retribution from the Ottoman era to the twentieth century and beyond. Basic Books. ISBN 0465027326. OCLC 49323460.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- Lazarević, Milutin D. (1955). Drugi Balkanski rat. Vojno delo.

- Gedeon, Dimitrios (1998). A concise history of the Balkan Wars, 1912–1913 (1.udg. ed.). Athens: Hellenic Army General Staff. p. 260. ISBN 978-960-7897-07-7.

- Schurman, Jacob Gould (2004). The Balkan Wars 1912 to 1913. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4191-5345-5.

- Skoko, Savo (1975). Drugi balkanski rat 1913: Tok i završetak rata. Vojnoistorijski Institut.

Further reading

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 978-2825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405142915.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521274593.

External links

- Hall, Richard C.: Balkan Wars 1912–1913 , in: 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.