Second generation of video game consoles

In the history of video games, the second-generation era refers to computer and video games, video game consoles, and handheld video game consoles available from 1976 to 1992. Notable platforms of the second generation include the Fairchild Channel F, Atari 2600, Intellivision, Odyssey 2, and ColecoVision. The generation began in November 1976 with the release of the Fairchild Channel F.[1] This was followed by the Atari 2600 in 1977,[2] Magnavox Odyssey² in 1978,[3] Intellivision in 1980[4] and then the Emerson Arcadia 2001, ColecoVision, Atari 5200, and Vectrex,[5] all in 1982. By the end of the era, there were over 15 different consoles. It coincided with, and was partly fuelled by, the golden age of arcade video games. This peak era of popularity and innovation for the medium resulted in many games for second generation home consoles being ports of arcade games. Space Invaders, the first "killer app" arcade game to be ported, was released in 1980 for the Atari 2600, though earlier Atari-published arcade games were ported to the 2600 previously.[6] Coleco packaged Nintendo's Donkey Kong with the ColecoVision when it was released in August 1982.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

Built-in games, like those from the first generation, saw limited use during this era. Though the first generation Magnavox Odyssey had put games on cartridge-like circuit cards, the games had limited functionality and required TV screen overlays and other accessories to be fully functional. More advanced cartridges, which contained the entire game experience, were developed for the Fairchild Channel F, and most video game systems adopted similar technology.[7] The first system of the generation and some others, such as the RCA Studio II, still came with built-in games[8] while also having the capability of utilizing cartridges.[9] The popularity of game cartridges grew after the release of the Atari 2600. From the late 1970s to the mid-1990s, most home video game systems used cartridges until the technology was replaced by optical discs. The Fairchild Channel F was also the first console to use a microprocessor, which was the driving technology that allowed the consoles to use cartridges.[10] Other technology such as screen resolution, color graphics, audio, and AI simulation was also improved during this era. The generation also saw the first handheld game cartridge system, the Microvision, which was released by toy company Milton Bradley in 1979.

In 1979, gaming giant Activision was created by former Atari programmers[11] and was the first third-party developer of video games.[12] By 1982, the shelf capacity of toy stores was overflowing with an overabundance of consoles, over-hyped game releases, and low-quality games from new third-party developers. An over-saturation of consoles and games,[13] coupled with poor knowledge of the market, saw the video game industry crash in 1983 and marked the start of the next generation. Beginning in December 1982 and stretching through all of 1984, the crash of 1983 caused major disruption to the North American market.[14][15] Some developers collapsed and almost no new games were released in 1984. The market did not fully recover until the third generation.[4] The second generation ended on January 1, 1992, with the discontinuation of the Atari 2600.[16]

Background

The primary driver of the second generation of consoles was the introduction of the low-cost microprocessor. Arcade games and the first generation of consoles used discrete electrical and electro-mechanical components including simple logic chips such as transistor-transistor logic (TTL)-based integrated circuits (ICs). Custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) like the AY-3-8500 were produced to replicate these circuits within a single chip, but still presented only a single fixed logic program,. Once a game was shipped, there were only minimal variations that could be made by adjusting the positions of jumpers (effectively the behavior of the "cartridges" that shipped with the Magnavox Odyssey). As Atari, Inc. recognized, spending from $100,000 to 250,000 and several months of development time on a hardware unit with a single dedicated game with only three-month shelf life before it was outdated by other competitors' offerings was not a practical business model, and instead some type of programmable console would be preferred.[17]

Intel introduced the first microprocessor, the 4004, in 1971, a special computer chip that could be sent a simple instruction and provide its result. This allowed the ability to create software programs around the microprocessor rather than fix the logic into circuits and ICs. Engineers at both Atari, Inc. (via its Cyan Engineering subsidiary) and at Alpex Computer Corporation saw the potential to apply this to home consoles as prices for microprocessors became more affordable. Alpex's work led to partnership with semiconductor manufacturer Fairchild Camera and Instrument and lead to the release of the first such programmable home console, the Fairchild Channel F released in 1976, based on the Fairchild F8 microprocessor. The Channel F also established the use of ROM cartridges to provide the software for the programmable console, consisting of a ROM chip mounted on a circuit board within a hard casing that can withstand the physical insertion into the console and potential static electricity buildup.[18] Atari's own programmable console, the Atari Video Computer System (Atari VCS or later known as the Atari 2600), was released in 1977 and based on the MOS Technology 6507 microprocessor, with a cartridge design influenced in part by the Channel F system.[18] Other console manufacturers soon followed suit with the production of their own programmable consoles.

At the start of the second generation, all games were developed and produced in-house. Four former Atari programmers, having left from conflicts in management style after Atari was purchased by Warner Communications in 1976, established Activision in 1979 to develop their own VCS games, which included Kaboom! and Pitfall!. Atari sued Activision on the basis of theft of trade secrets and violation of their non-disclosure agreements, but the two companies settled out of court in 1982, with Activision agreeing to pay a small license fee to Atari for every game of theirs they sold. This established Activision as the first third-party developer for a console. This also established a working model for licensing other third-party developers, which several companies followed in Activision's wake, partially contributing to the video game crash of 1983 due to oversaturation.[19]

As the second generation of consoles coincided with the golden age of arcade video games, a common trend that emerged during the generation was licensing arcade video games for consoles. Many of them were increasingly licensed from Japanese video game companies by 1980, which led to Jonathan Greenberg of Forbes predicting in early 1981 that Japanese companies would eventually dominate the North American video game industry later in the decade.[20]

At this stage, both consoles and game cartridges were intended to be sold for profit by manufacturers. However, by segregating games from the console, this approach established the use of the razorblade business model in future console generations, where consoles would be sold at or below cost while licensing fees from third-party games would bring in profits.[21][22]

Home systems

Fairchild Channel F

The Fairchild Channel F, also known early in its life as the Fairchild Video Entertainment System (VES), was released by Fairchild Semiconductor in November 1976 and was the first console of the second generation.[23] It was the world's first CPU-based video game console, introducing the cartridge-based game-code storage format.[24] The console featured a pause button that allowed players to freeze a game. This allowed them to take a break without the need to reset or turn off the console so they did not lose their current game progress.[25] Fairchild released twenty-six cartridges for the system, with up to four games being on each cartridge. The console came with two pre-installed games, Hockey and Tennis.[26]

Following the release of the Atari 2600, the Channel F's popularity waned quickly as the more action-driven games of the Atari 2600 drew more attention than the more educational and slow-paced games on the Channel F. By 1979, only an additional 100,000 units of the Channel F were sold for lifetime sales of 350,000.[27]

In 1978, Fairchild redesigned the system into a new model, the Channel F System II. The System II streamlined some of the initial Channel F to reduce cost and improve consumer usage compared to the Atari 2600, such as improved controller connections and using the television speakers for audio output, but by the time it was released, the Atari 2600 has too much market advantage for Fairchild to overcome. After releasing only six games for the system, Fairchild sold the Channel F technology to Zircon International in 1979, which discontinued the system by 1983.[27]

Atari 2600 and 5200

In 1977, Atari released its CPU-based console called the Video Computer System (VCS), later called the Atari 2600.[28] Nine games were designed and released for the holiday season. Atari held exclusive rights to most of the popular arcade game conversions of the day. They used this key segment to support their older hardware in the market. This game advantage and the difference in price between the machines meant that each year, Atari sold more units than Intellivision, lengthening its lead despite inferior graphics.[29] The Atari 2600 sold over 30 million units over its lifetime, considerably more than any other console of the second generation.[30] In 1982, Atari released the Atari 5200 in an attempt to compete with the Intellivision. While superior to the 2600, poor sales and lack of new games meant Atari only supported it for two years before it was discontinued.[31]

Early Atari 2600 cartridges contained 2 kilobytes of read-only storage. This limit grew steadily from 1978 to 1983: up to 16 kilobytes for Atari 5200 cartridges. Bank switching, a technique that allowed two different parts of the program to use the same memory addresses, was required for the larger cartridges to work. The Atari 2600 cartridges got as large as 32 kilobytes through this technique.[32] The Atari 2600 had only 128 bytes of RAM available in the console. A few late game cartridges contained a combined RAM/ROM chip, thus adding another 256 bytes of RAM inside the cartridge itself. The Atari standard joystick was a digital controller with a single button, released in 1977.[33]

Bally Astrocade

The Bally Astrocade was released in 1977 and was available only through mail order.[34] It was originally referred to as the Bally Home Library Computer.[34][35] Delays in the production meant that none of the units shipped until 1978. By this time, the machine had been renamed the Bally Professional Arcade.[35] In this form, it sold mostly at computer stores and had little retail exposure, unlike the Atari VCS. The rights to the console were sold to Astrovision in 1981. They re-released the unit with the BASIC cartridge included for free; this system was known as the Bally Computer System.[35] When Astrovision changed their name to Astrocade in 1982 they also changed the name of the console to the Astrocade to follow suit. It sold under this name until the video game crash of 1983 when it was discontinued.[36]

Magnavox Odyssey 2

In 1978, Magnavox released its microprocessor-based console, the Odyssey 2, in the United States and Canada.[37] It was distributed by Philips Electronics in the European market and was released as the Philips G7000.[38] A defining feature of the system was the speech synthesis unit add-on which enhanced music, sound effects and speech capabilities.[39] The Odyssey² was also known for its fusion of board and video games. Some titles came with a game board and pieces which players had to use in conjunction to play the game. Although the Odyssey² never became as popular as the Atari consoles, it sold 2 million units throughout its lifetime. This made it the third best selling console of the generation.[40] It was discontinued in 1984.[41]

Intellivision

The Intellivision was introduced by Mattel to test markets in 1979[42] and nationally in 1980. The Intellivision console contained a 16-bit processor with 16-bit registers and 16-bit system RAM. This was long before the "16-bit era".[43] Programs were however stored on 10-bit ROM. It also featured an advanced sound chip that could deliver output through three distinct sound channels.[43] The Intellivision was the first console with a thumb-pad directional controller and tile-based playfields with vertical and horizontal scrolling. The system's initial production run sold out shortly after its national launch in 1980.[43] Early cartridges were 4 kilobyte ROMs, which grew to 24 kilobytes for later games.

The Intellivision introduced several new features to the second generation. It was the first home console to use a 16-bit microprocessor and offer downloadable content through the PlayCable service.[44] It also provided real-time human voices during gameplay. It was the first console to pose a serious threat to Atari's dominance. A series of TV advertisements featuring George Plimpton were run. They used side-by-side game comparisons to show the improved graphics and sound compared with those of the Atari 2600.[43] It sold over 3 million units[45] before being discontinued in 1990.[46]

ColecoVision

The ColecoVision was introduced by toy manufacturer Coleco in August 1982. It was more powerful than previous consoles, providing an experience that was closer to Arcades than what the 2600 could provide.[47] The console launched with several arcade ports, including Sega's Zaxxon, and later saw third-party support from many developers such as Activision and even their competitor Atari.[48] The ColecoVision is notable for its Atari 2600 expansion module, which enabled the console to play 2600 games, resulting in a lawsuit from Atari.[49] The ColecoVision was a victim of the video game crash, ultimately being discontinued in 1985.

Vectrex

The Vectrex was released in 1982. It was unique among home systems of the time in featuring vector graphics and its own self-contained display.[50] At the time, many of the most popular arcade games used vector displays. Through a licensing deal with Cinematronics, GCE was able to produce high-quality versions of arcade games such as Space Wars and Armor Attack. Despite a strong library of games and good reviews, the Vectrex was ultimately a commercial failure.[51] It was on the market for less than two years.[52]

Comparison

| Name | Fairchild Channel F | Atari 2600 | Bally Astrocade | Magnavox Odyssey² | Intellivision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Fairchild Semiconductor | Atari | Bally Technologies | Magnavox | Mattel | |

| Image(s) |   |

|

|

|

| |

| Launch price | US$169.95 (equivalent to $870 in 2022) | US$199[53] (equivalent to $970 in 2022) | US$299[34] (equivalent to $1,440 in 2022) | US$200 (equivalent to $900 in 2022) | US$299[42] (equivalent to $1,060 in 2022) | |

| Release date |

|

|||||

| Media | Cartridge | Cartridge and Cassette (Cassette available via special 3rd party attachment) | Cartridge and cassette/Floppy, available with ZGRASS unit | Cartridge | Cartridge | |

| Top-selling games | Videocart-17: Pinball Challenge | Pac-Man, 7 million (as of September 1, 2006)[56][57] | Unknown | Unknown | :Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack, 1.939 million Major League Baseball, 1.085 million (as of June 1983)[58][59] | |

| Backward compatibility | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | Atari 2600 games through the System Changer module | |

| Accessories (retail) | None |

|

|

|

| |

| CPU | 1.79 MHz (PAL 2.00 MHz) Fairchild F8 | 1.19 MHz MOS Technology 6507 | 1.789 MHz Zilog Z80 | 1.79 MHz Intel 8048 8-bit microcontroller | 2 MHz General Instrument CP1610 | |

| Memory | Main RAM 64 bytes Video RAM 2 kB (2×128×64 bits) |

128 bytes RAM within MOS Technology RIOT chip (additional RAM may be included in game cartridges) | Main RAM 4 kB (up to 64 kB with external modules in the expansion port) | CPU-internal RAM: 64 bytes Audio/video RAM: 128 bytes |

352 x 16-bit system RAM 240 x 8-bit scratchpad RAM | |

| Video | Resolution |

102×58 to 128×64[60] |

160×192 (sprites) |

True: 160×102 |

160×200 (NTSC) |

160x96 (20x12 tiles of 8x8 pixels) |

| Palette |

8 colors |

128 colors (NTSC) |

32 colors (8 intensities) |

16 colors (fixed); sprites use 8 colors |

16 color | |

| Colors on Screen |

8 simultaneous (maximum of 4 per scanline) |

128 simultaneous (2 background colors and 2 sprite colors (1 color per sprite) per scanline) |

True: 8 |

Unknown |

16 simultaneous | |

| Sprites |

1 |

2 sprites, 2 missiles, and 1 ball per scanline |

Unlimited (software controlled) |

|

8 sprites, 8x16 half-pixels | |

| Other | Vertical and horizontal scrolling | |||||

| Audio | Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

| |

| Name | Emerson Arcadia 2001 | ColecoVision | Atari 5200 | Vectrex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Emerson Radio Corporation | Coleco | Atari | General Consumer Electric and Milton Bradley | |

| Image(s) |  |

|

|

| |

| Launch price | US$200 (equivalent to $610 in 2022)[61] | US$175[53] (equivalent to $530 in 2022) | US$270[53] (equivalent to $820 in 2022) | US$199[63] (equivalent to $600 in 2022) | |

| Release date |

|

||||

| Media | Cartridge[61] | Cartridge and Cassette, available with Expansion #3 | Cartridge | Cartridge | |

| Top-selling games | N/A | Donkey Kong (pack-in) | N/A | N/A | |

| Backward compatibility | N/A | Compatible with Atari 2600 Via Expansion #1 | Atari 2600 games through the 2600 cartridge adapter | N/A | |

| Accessories (retail) | N/A |

|

|

| |

| CPU | 3.58 MHz Signetics 2650 CPU | 3.58 MHz Zilog Z80A | 1.79 MHz Custom MOS 6502C | 1.5 MHz Motorola 68A09 | |

| Memory | 512 bytes RAM | Main RAM 1 kB Video RAM 16 kB |

Main RAM 16 kB DRAM | Main RAM 1 kB | |

| Video | Resolution |

128x208 / 128×104 |

256×192 |

80×192 (16 color) |

|

| Palette |

16 colors |

15 colors, 1 transparent |

256 colors |

2 (black and white) | |

| Colors on Screen |

16 simultaneous (1 color per sprite) |

16 simultaneous,[64] Up to 256 (16 hues, 16 luma) on screen (16 per scanline) with display list interrupts |

2 simultaneous (black and white) | ||

| Sprites |

32 sprites (4 per scanline), 8×8 or 8×16 pixels, integer zoom |

8 single-color sprites, full height of display; 1/2/4x width scaling |

|||

| Other |

Tilemap playfield, 8×8 tiles |

Built in vector CRT | |||

| Audio | Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio with:

|

Mono audio (built-in speaker)

| |

Sales standings

The best-selling console of the second generation was the Atari 2600 at 30 million units.[66] As of 1990, the Intellivision had sold 3 million units.[67][42][46] This is around 1 million higher than the Odyssey² and ColecoVision sales[68][69] and eight times the number of purchases for the Fairchild Channel F, which was 350,000 units.[18]

| Console | Units sold worldwide |

|---|---|

| Atari 2600 | 30 million (as of 2004)[66] |

| Intellivision | 3 million (as of 2004)[45][42][70] |

| ColecoVision | 2 million (as of 1983)[71] |

| Magnavox Odyssey² | 2 million (as of 2005)[40] |

| Atari 5200 | 1 million (as of 1984)[72] |

| Fairchild Channel F | 350,000 (as of 1979)[18] |

| Bally Astrocade | Unknown |

| Emerson Arcadia 2001 | Unknown |

| Vectrex | Unknown |

Other consoles

Compact Vision TV Boy (released in 1983)[76]

Compact Vision TV Boy (released in 1983)[76]

Handheld systems

Microvision

The Microvision, manufactured and sold by Milton-Bradley. was released in 1979.[77] It was the first handheld game console that used cartridges that could be swapped out and that contained their own processor as the console itself had no on-board processor. It had a small game library which was prone to damage from static electricity and the LCD screen could also rot. These two factors contributed to its discontinuation two years after release.

Entex Select-A-Game and Adventure Vision

Entex released two handheld systems in the second generation, the Select-A-Game and the Adventure Vision. There were 6 games available for the Select-A-Game but it was only available for a year until focus shifted to the Adventure Vision which was released in the following year.

The Adventure Vision was released only in North America in 1982 by Entex and was the successor to the Select-A-Game.[78] It was unique among the consoles as it used a spinning mirror system for its built-in display and had to be used set down on a surface due to its size and shape.[79] It was discontinued one year later in 1983 after selling just over fifty thousand units.[78]

Palmtex Super Micro

Developed and manufactured by Palmtex, the Super Micro was released in 1984 and discontinued later that year. Due to financial problems between Palmtex and Home Computer Software, only three games were released for the system despite more being planned. It was criticized for its poor build quality and how easily it would break, and sold fewer than 37,000 units.

Epoch Game Pocket Computer

The Epoch Game Pocket Computer was released in Japan in 1984.[80] Due to poor sales, only five games were made for it and was not released outside of Japan.[81]

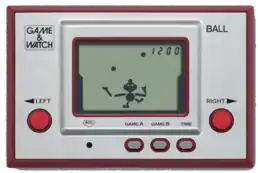

Nintendo Game & Watch

The Game & Watch was a series of 60 handheld consoles that contained a single game in each release. The first, titled "Ball" was released in 1980 and titles were released up until it was discontinued in 1991.[78] Unlike the other handheld consoles in the second generation, the Game & Watch had a segmented LCD screen similar to a digital watch which limited the display to the configuration of the segments. The series sold a combined 43.4 million units, making it the most popular handheld of the generation.

Comparison

| Console | Microvision | Entex Select-A-Game | Adventure Vision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Milton Bradley | Entex Industries | Entex Industries |

| Image |  |

|

|

| Launch price | US$49.99 (equivalent to $160.41 in 2014)[82] | US$59 (equivalent to $190 in 2022)[83] | US$79.99 (equivalent to $243 in 2022) |

| Release date | November 1979[84] | 1981[85] | 1982 |

| Units sold | Unknown | Unknown | 50,757 |

| Media | Cartridge | Cartridge | Cartridge |

| CPU | Main: None

Cartridge: 100 kHz Intel 8021 |

Main: None (CPU was contained within the cartridge)

Cartridge: Hitachi HD38800 |

733 kHz Intel 8048 |

| Memory | 64 bytes RAM | 64 bytes RAM (on CPU)

1 kilobyte (on main PCB) | |

| Video | 16 x 16 pixel LCD | 7 x 16 pixel VFD

2 colors (red and blue) |

150 x 40 pixel spinning mirror system

Monochrome |

| Audio | Piezo Buzzer | National Semiconductor COP411L @ 52.6 kHz |

| Console | Super Micro | Epoch Game Pocket Computer | Game & Watch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Palmtex | Epoch | Nintendo |

| Image |  |

|

|

| Launch price | US$39.95 (equivalent to $113 in 2022) | ¥12,800 (equivalent to ¥15,516 in 2019)[86] | ¥5,800 (equivalent to ¥7,031 in 2019)[87] |

| Release date | May 1984[88] | November 1984[86] | April 28, 1980 |

| Units sold | Fewer than 37,200 | Unknown | 43.4 million[89] |

| Media | Cartridge | Cartridge | 1 built in game per device |

| CPU | None (CPU was contained within the cartridge) | 6 MHz NEC D78c06 | |

| Memory | 2 kilobytes RAM | ||

| Video | 32 x 16 pixel LCD

57.15 x 38.1mm |

75 x 64 pixel LCD | Segmented LCD |

| Audio | Piezo Buzzer |

Software

Milestone titles

- Advanced Dungeons and Dragons: Cloudy Mountain (Intellivision) by Mattel Electronics won an award in the "1984 Best Adventure Videogame" category at the 5th Annual Arkie Awards.[90] It was the first Intellivision cartridge to have more than 4K of ROM.[91]

- Adventure (Atari 2600) by Atari, Inc. was the first action-adventure video game[92] and first console fantasy game.[93] It is considered to be an important role in the advancement of home video games[94] and one of the best Atari 2600 titles.[95]

- Asteroids (arcade port) (Atari 2600) was the first game on the 2600 to utilize the bank switching technique.[96]

- Baseball (Intellivision) by Mattel was the console's best selling title with over one million copies sold.[58]

- Demon Attack (Atari 2600) by Imagic was released in 1983. It won the 1983 Arcade Award for "Best Videogame of the Year".[97] It was the company's best selling game and is considered a classic of the Atari 2600.[98][99][100]

- Donkey Kong (arcade port) (ColecoVision) by Coleco was praised highly for being very faithful to the original arcade game. Critics considered it the best version out of the ColecoVision, Atari and Intellivision ports.[39][101]

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Atari 2600) released in 1982[102] and is often accredited to being one of the worst games of all time.[103] Some believe the game played a significant role in the video game crash of 1983.[104]

- Microsurgeon (Intellivision) by Imagic was praised highly for its originality.[39] It was included in "The Art of Video Games" exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in 2012.[105]

- Missile Command (arcade port) (Atari 2600) by Atari, Inc. was released in 1981 and sold more than 2.5 million copies.[106] This made it the third best selling game on the console.[107]

- Pitfall! (Atari 2600) by Activision, released in 1982,[108] was one of the best selling games for the Atari 2600, selling over 4 million copies.[109] Pitfall popularized the side-scrolling platformer genre.[110]

- Pitfall II: Lost Caverns (Atari 2600) by Activision, released in 1984[111] was one of the most technically impressive titles for the 2600.[112] It came with a specialized audio chip on the cartridge that allowed for advanced music capabilities where music could be changed dynamically.[113]

- River Raid (Atari 2600) by Activision was the first video game to be banned for minors in West Germany.[114] Despite this, it was still one of the most popular titles for the Atari 2600 and won an award for "1984 Best Action Videogame".[115]

- Space Invaders (arcade port) (Atari 2600) by Taito was the first official licensing of an arcade game and was the first "killer app" for video game consoles.[6][116] Its release saw sales of the Atari 2600 quadruple[116] and was the first title to sell 1 million copies.[117]

- Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (Atari 2600) by Parker Brothers was the first officially licensed video game of the Star Wars franchise.[118]

- Utopia (Intellivision) by Don Daglow is often credited with being the first real-time strategy that laid the foundation for many games within the genre.[119][120]

- Zaxxon (arcade port) (ColecoVision) by Sega was the first home console game to utilize isometric graphics.[121]

See also

References

- Leigh, Peter (November 1, 2018). The Nostalgia Nerd's Retro Tech: Computer, Consoles & Games. Octopus. ISBN 9781781576823. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Forster, Winnie (2005). The encyclopedia of consoles, handhelds & home computers 1972-2005. GAMEPLAN. p. 27. ISBN 3-00-015359-4.

- Matthewson, David K. (1982). Beginner's Guide to Video. Butterworth. p. 180. ISBN 9780408005777. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. ABC-CLIO. p. 135. ISBN 9780313379369. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Barton, Matt and Loguidice, Bill. (2007). A History of Gaming Platforms: The Vectrex Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Gamasutra.

- Campbell, Stuart (September 2007). "The Definitive Space Invaders". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (41): 24–33.

- Cohen, D. S. (September 18, 2018). "Jerry Lawson - First Black Video Game Professional". Lifewire. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Dillon, Roberto (2011). The Golden Age of Video Games. A K Peter/CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-7323-6.

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Hardawar, Devindra (February 20, 2015). "Jerry Lawson, a self-taught engineer, gave us video game cartridges". Engadget. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Weiss, Brett (April 4, 2011). Classic Home Video Games, 1972_1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 28. ISBN 9780786487554. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- "Stream of video games is endless". Milwaukee Journal. December 26, 1982. pp. Business 1. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Kleinfield, N.R. (October 17, 1983). "Video Games Industry Comes Down To Earth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- Dvorchak, Robert (July 30, 1989). "NEC out to dazzle Nintendo fans". The Times-News. p. 1D. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2008). The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 9780313338687. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). Racing the Beam. MIT Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-2625-3976-0.

- Fulton, Steve (November 6, 2007). "The History of Atari: 1971-1977". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Flemming, Jeffrey. "The History Of Activision". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Greenberg, Jonathan (April 13, 1981). "Japanese invaders: Move over Asteroids and Defenders, the next adversary in the electronic video game wars may be even tougher to beat" (PDF). Forbes. Vol. 127, no. 8. pp. 98, 102. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- Ernkvist, Mirko (2008). "Down many times, but still playing the game: Creative destruction and industry crashes in the early video game industry 1971-1986". In Gratzer, Karl; Stiefel, Dieter (eds.). History of Insolvancy and Bankruptcy. Södertörns högskola. pp. 161–191. ISBN 978-91-89315-94-5.

- Conley, James; Andros, Ed; Chinai, Priti; Lipkowitz, Elise; Perez, David (Spring 2004). "Use of a Game Over: Emulation and the Video Game Industry, A White Paper". Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property. 2 (2). Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- Manuela, Cruz-Cunha, Maria (February 29, 2012). Handbook of Research on Serious Games as Educational, Business and Research Tools. IGI Global. p. 318. ISBN 9781466601505. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wolf, Mark (2008). The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beyond. Greenwood Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- Weiss, Brett (December 20, 2011). Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 203. ISBN 9780786487554. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Barton, Matt (January 9, 2009). "The History Of Pong: Avoid Missing Game to Start Industry". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Barton, Matt; Loguidice, Bill (February 28, 2008). "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Barton, Matt; Loguidice, Bill (May 8, 2008). "A History of Gaming Platforms: Mattel Intellivision". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Dillon, Roberto (April 19, 2016). The Golden Age of Video Games: The Birth of a Multibillion Dollar Industry. CRC Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781439873243. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. ABC-CLIO. p. 49. ISBN 9780313379369. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Monfort, Nick & Bogost, Ian (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- Barton, Matt; Loguidice, Bill (February 28, 2008). "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Scientific American Magazine. 1977. pp. 15–17.

- Weiss, Brett (April 4, 2011). Classic Home Video Games, 1972_1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 18. ISBN 9780786487554. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (November 21, 2018). The Routledge Companion to Media Technology and Obsolescence. Routledge. ISBN 9781315442662. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Game Informer Magazine: For Video Game Enthusiasts. Sunrise Publications. May 2009. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- Bernal-Merino, Miguel Á (September 19, 2014). Translation and Localisation in Video Games: Making Entertainment Software Global. Routledge. ISBN 9781317617839. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Goodman, Danny (Spring 1983). "Home Video Games: Video Games Update". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. p. 32. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Forster, Winnie (2005). The encyclopedia of consoles, handhelds & home computers 1972 - 2005. GAMEPLAN. p. 30. ISBN 3-00-015359-4.

- "The Odyssey2 Timeline! - The Odyssey² Homepage!". www.the-nextlevel.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Robinson, Keith; Roney, Stephen. "Ask Hal: Frequently Asked Questions to the Blue Sky Rangers". Intellivision Productions. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- Barton, Matt and Loguidice, Bill. (May 8, 2008). A History of Gaming Platforms: Mattel Intellivision Archived November 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Gamasutra.

- "No. 9 Games by Wire". Next Generation. No. 29. Imagine Media. May 1997. p. 26.

- "Mattel Intellivision — 1980–1984". ClassicGaming. IGN. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Forster, Winnie (2005). The encyclopedia of consoles, handhelds & home computers 1972–2005. GAMEPLAN. p. 42. ISBN 3-00-015359-4.

- Aeppel, Timothy (December 10, 1982), "Zap! Pow! Video games sparkle in holiday market", Christian Science Monitor: 7,

In recent weeks, two particularly hot-selling systems have emerged - the Atari 5200 and ColecoVision. Both are described as powerful 'third wave' machines, the Cadillacs of game systems, and priced accordingly at close to $200...[T]hey are sure to snatch most of the Christmas market.

- "Galaxian (ColecoVision) - The Cutting Room Floor". tcrf.net. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Atari-Coleco Pact". the New York Times. March 12, 1983. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Barton, Matt and Loguidice, Bill. (2007). A History of Gaming Platforms: The Vectrex Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Gamasutra.

- Herman, Leonard (January 1, 1997). Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames. Rolenta Press. ISBN 9780964384828. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- Weiss, Brett (December 20, 2011). Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 274. ISBN 9780786487554. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Dornbush, Jonathon (October 4, 2016). "Update: Comparing the Price of Every Game Console, With Inflation". IGN. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Mabuchi, Hiroaki (December 29, 2016). "テレビテニスから始まった国内家庭用ゲーム機の移り変わり". IGN Japan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 9780313379369. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Jeremy Reimer (September 1, 2006). "EA's Madden 2007 sells briskly, but are games gaining on movies?". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Kent, Steven (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Fox, Matt (December 1, 2012). The Video Games Guide: 1,000+ Arcade, Console and Computer Games, 1962-2012, 2d ed. McFarland. p. 179. ISBN 9781476600673. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Intellivision Lives CD PC/Mac. Intellivision Productions. 1998.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (June 15, 2012). Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Wayne State University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780814337226. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- Cohen, Henry (1982). Electronic Games (PDF). pp. 100–105. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- M.B. Mook (2016). Nostalgic Famicon Perfect Guide. Japan. p. 101.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kent, Steven L. (2000). The First Quarter: A 25-Year History of Video Games. BWD Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780970475503. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Atari 8-bit Forever by Bostjan Gorisek". Atari 8-bit Forever. October 18, 2018. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- Weigers, Karl E. (December 1985). "Atari Fine Scrolling". Compute! (67): 110. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- Ciesla, Robert (July 19, 2017). Mostly Codeless Game Development: New School Game Engines. Apress. p. 162. ISBN 9781484229705. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- "Mattel Intellivision – 1980–1984". ClassicGaming. IGN. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ Forster, Winnie (2005). The encyclopedia of consoles, handhelds & home computers 1972 – 2005. GAMEPLAN. p. 30. ISBN 3-00-015359-4.

- Coleco Industries sales report, PR Newswire, April 17, 1984,

'First quarter sales of ColecoVision were substantial, although much less that [sic] those for the year ago quarter,' Greenberg said in a prepared statement. He said the company has sold 2 million ColecoVision games since its introduction in 1982.

- "Intellivision Productions Timeline". Intellivision Productions. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- "Coleco Industries, Inc. 1983 Annual Report". Coleco Industries, Inc. 1983: 3. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

The year's sales of 1.5 million ColecoVision units brought the installed base to over 2 million units worldwide.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Schrage, Michael (May 22, 1984). "Atari Introduces Game In Attempt for Survival". Washington Post. p. C3.

The company has stopped producing its 5200 SuperSystem games player, more than 1 million of which were sold.

- Edwards, Benj (October 27, 2017). "Rediscovering History's Lost First Female Video Game Designer". Fast Company. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Lithner, Martin Tobias (January 14, 2019). Super Retro:id: A Collector's Guide to Vintage Consoles. BoD - Books on Demand. ISBN 9789177856771. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Fox, Matt (December 1, 2012). The Video Games Guide: 1,000+ Arcade, Console and Computer Games, 1962-2012, 2d ed. McFarland. p. 354. ISBN 9781476600673. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Baker, Kevin (May 23, 2013). The Ultimate Guide to Classic Game Consoles. eBookIt.com. ISBN 9781456617080. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Weiss, Brett (2007). Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 243. ISBN 9780786432264. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- Blythe, Daniel (December 13, 2011). Collecting Gadgets and Games from the 1950s-90s. Pen and Sword. p. 109. ISBN 9781844681051. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Weiss, Brett (December 20, 2011). Classic Home Video Games, 1972-1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 9780786487554. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Amos, Evan (November 6, 2018). The Game Console: A Photographic History from Atari to Xbox. No Starch Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781593277727. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- Amos, Evan (November 6, 2018). The Game Console: A Photographic History from Atari to Xbox. No Starch Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781593277727. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- "Milton Bradley Microvision – Pop Culture Maven". February 19, 2014. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- Amos, Evan (November 6, 2018). The Game Console: A Photographic History from Atari to Xbox. No Starch Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781593277727. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- コアムックシリーズNO.682『電子ゲーム なつかしブック』p.46.

- Butler, Judith; Bulter, Kirt Charles (1997). Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. Psychology Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780415915885. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- 功, 山崎 (April 20, 2018). 懐かしの電子ゲーム大博覧会 (in Japanese). 主婦の友社. p. 58. ISBN 9784074310593. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- "Iwata Asks". iwataasks.nintendo.com. April 2010. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- "Hand-Held Cartridges". Technocracy. Joystik: How to Win at Video Games. Vol. 1, no. 6. Skokie, Illinois: Publications International. July 1983. p. 62.

- "Iwata Asks". Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (January 1984). "Arcade Alley: The Arcade Awards, Part 1". Video. Vol. 7, no. 10. Reese Communications. pp. 40–42. ISSN 0147-8907.

- Andersen, Helge (December 1983). "Intellivision: Spiel Perfekt" (Artikelscan). TeleMatch (7/83): 38–40. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- Buchana, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (2001). "5: Narrative in the Video Game". In Mark J. P. Wolf (ed.). The Medium of the Video Game. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292791503.

- Wolf 2001, p. 97.

- Mark J.P. Wolf, Bernard Perron, ed. (2013). The Video Game Theory Reader. Routledge. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-1352-0518-8.

- Grand, Joe; Mitnick, Kevin D.; Russell, Ryan (January 29, 2004). Hardware Hacking: Have Fun while Voiding your Warranty. Elsevier. p. 229. ISBN 9780080478258. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2020.

- "The Players Guide to Fantasy Games". Electronic Games. June 1983. p. 47. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- Weiss, Brett Alan. "Demon Attack". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (February 1983). "Arcade Alley: The Fourth Annual Arcade Awards". Video. Reese Communications. 6 (11): 30, 108. ISSN 0147-8907.

- Barton, Matt and Bill Loguidice. "A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS Archived March 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". Gamasutra. February 28, 2008.

- Katz, Arnie (September 26, 1982). "Arcade Express" (PDF). Reese Publishing Co. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- "E.T.™ NEEDS YOUR HELP!". AtariAge. Atari Age. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- Guins, Raifrod (2009). "Concrete and Clay: The Life and Afterlife of E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial for the Atari 2600". Design and Culture. 1 (3): 345–364. doi:10.1080/17547075.2009.11643295. S2CID 191413087.

- Dvorak, John C (August 12, 1985). "Is the PCJr Doomed To Be Landfill?". InfoWorld. 7 (32): 64. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "Exhibitions: The Art of Video Games / American Art". Americanart.si.edu. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- Wallis, Alistair (November 23, 2006). "Playing Catch Up: Night Trap 's Rob Fulop". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Cifaldi, Frank (September 6, 2012). "Living in Pitfall! 's shadow". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Bogost, Ian; Montfort, Nick (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- Morales, Aaron (January 25, 2013). "The 10 best Atari games". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- Hague, James. "The Giant List of Classic Game Programmers". Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Jones, Darran; Hunt, Stuart (January 1, 2008). "Top 25 Atari 2600 Games". Retro Gamer. No. 46. Imagine Publishing Ltd. p. 33.

- Santos, Wayne (December 1, 2006). GameAxis Unwired. SPH Magazines. p. 39. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (January 1, 2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: A-L. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313379369. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (February 1984). "Arcade Alley: The 1984 Arcade Awards, Part II". Video. Reese Communications. 7 (11): 28–29. ISSN 0147-8907.

- Kent, Steven (2001). Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Weiss, Brett (2007). Classic home video games, 1972–1984: a complete reference guide. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7864-3226-4.

- Bogost, Ian; Montfort, Nick (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- Moss, Richard (September 15, 2017). "Build, gather, brawl, repeat: The history of real-time strategy games". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (2009). Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time. Boston: Focal Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0240811468.

- Wolf, Mark J. P.; Perron, Bernard (October 8, 2013). The Video Game Theory Reader. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 9781135205195. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.