Seima-Turbino phenomenon

The Seima-Turbino phenomenon is a pattern of burial sites with similar bronze artifacts dated to c. 2300–1700 BCE[2] (2017 dated from 2100–1900 BCE,[3] 2007 dated to 1650 BCE onwards[4]) found across northern Eurasia, particularly Siberia and Central Asia,[3] maybe from Fennoscandia to Mongolia, Northeast China, Russian Far East, Korea, and Japan.[5][6] The homeland is considered to be the Altai Mountains.[3] These findings have suggested a common point of cultural origin, possession of advanced metal working technology, and unexplained rapid migration. The buried were nomadic warriors and metal-workers, traveling on horseback or two-wheeled carts.[7]

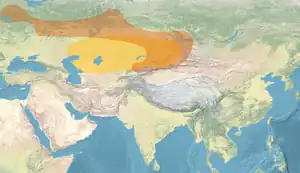

The Seima-Turbino phenomenon ( ) in Eurasia.[1]

| |

| Geographical range | Northern Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 2100 BC – 1650 BC |

| Preceded by | Afanasievo culture, Corded Ware culture, Sintashta culture, Andronovo culture, Okunev culture |

| Followed by | Karasuk culture |

The name derives from the Seyma cemetery near the confluence of the Oka River and Volga River, first excavated around 1914, and the Turbino cemetery in Perm, first excavated in 1924.[7]

Origin

Seima-Turbino (ST) weapons contain tin bronze ore originating from the Altai Mountains region (central Mongolia and southern Siberia), with further ST discoveries pointing more specifically to the southeastern portions of the Altai and Xinjiang.[3] These sites have been identified with the origin of the mysterious ST culture.[8]

Artifacts and weapons

The bronzes found were technologically advanced for the time, including lost wax casting, and showed high degree of artist input in their design.[9] Horses were the most common shapes for the hilts of blades.[3] Weapons such as spearheads with hooks, single-bladed knives and socketed axes with geometric designs traveled west and east from Xinjiang.[10]

Dispersal

The culture spread from the Altai mountains to the west and to the east.[11]

These cultures are noted for being nomadic forest and steppe societies with metal working, sometimes without having first developed agricultural methods.[8] The development of this metalworking ability appears to have occurred quite quickly.[11]

ST bronzes have been discovered as far west as the Baltic Sea[3] and the Borodino treasure in Moldavia.[12] [13]

Theories

Transmission into Southeast Asia

It has been conjectured that changes in climate in this region around 2000 BCE and the ensuing ecological, economic and political changes triggered a rapid and massive migration westward into northeast Europe, eastward into Korea, and southward into Southeast Asia (Vietnam and Thailand) across a frontier of some 4,000 miles. Supposedly this migration took place in just five to six generations and enabled people from Finland in the west to Thailand in the east to employ the same metal working technology and in some areas, horse breeding and riding.[5]

However, further excavations and research in Ban Chiang and Ban Non Wat (both Thailand) argue the idea that Seima-Turbino brought metal workings into southeast Asia is based on inaccurate and unreliable radiocarbon dating at the site of Ban Chiang. It is now agreed by virtually every specialist in Southeast Asian prehistory that the Bronze Age of Southeast Asia occurred too late to be related to ST, and the cast bronzes are quite different.[14]

.png.webp)

Uralic urheimat

The same authors conjectured that the same migrations spread the Uralic languages across Europe and Asia.[5]

The existence of Uralic Samoyedic and Ob-Ugrian groups like the Nenets, Mansi and Khanty, anchor the Uralic languages in Asia.

Notable is the similarity between the range of haplogroup N3a3’6, especially in the western part of Eurasia and the distribution of the Seima-Turbino trans-cultural phenomenon during the interval of 4.2–3.7 kya.[15] Carriers of N3a1-B211, the early branch of N3a, could have migrated to the eastern fringes of Europe by the same Seima-Turbino groups. However earlier migrations cannot be ruled out either; a study of ancient DNA revealed a 7,500 year-old influx from Siberia to northeast Europe.[16][17]

Another subclade of Y haplogroup N, N1a2b-P43 (TMRCA 4,700 ybp 95% CI 3,800 ⟷ 5,600 ybp,[18]), reaches some of its highest frequencies among the Uralic-speaking Nenets, Nganasan, Khanty, and Mansi peoples in western Siberia. Haplogroup N1a2b-P43 is also often observed among the members of many Uralic- or Turkic-speaking ethnic minorities of European Russia, but it is very rare among the Baltic Finnic and Samic peoples of Northern Europe. Estimated to be approximately 4,700 years old, N1b spread north and westwards from its original locus in Southern Siberia, exactly as Seima-Turbino migration did.

Genetics

Childebayeva et al. (2023) analysed DNA from nine individuals (eight males and one female) buried at the Seima-Turbino-associated site of Rostovka in Omsk (Russia), one of the few Seima-Turbino sites with preserved human remains. The individuals were found to have diverse ancestry components ranging between a genetic profile represented by the Western Steppe Middle-Late Bronze Age (similar to the Sintashta culture) and that of the Late Neolithic/Bronze Age East Siberians. One male could be modelled as deriving their ancestry entirely from Sintashta Middle-Late Bronze Age. Two males were assigned to the Y-haplogroup R1a (R1a-M417 and R1a-Z645), two to C2a, one to N1a1a1a1a (N-L392), one to Q1b (Q-M346), and one to R1b1a1a (R1b-M73). The mtDNA haplogroups of the individuals included those common in both east Eurasia (A10, C1, C4, G2a1) and west Eurasia (H1, H101, U5a, R1b, R1a). According to the study authors, the observed genetic heterogeneity among the individuals "can either suggest a group at an early stage of admixture, or signify the heterogeneous nature of the Seima-Turbino complex."[19]

Gallery

Spearheads from Turbino cemetery

Spearheads from Turbino cemetery

.jpg.webp) Bronze sculpture

Bronze sculpture Bronze figurine

Bronze figurine

References

- Bjørn, Rasmus G. (January 2022). "Indo-European loanwords and exchange in Bronze Age Central and East Asia: Six new perspectives on prehistoric exchange in the Eastern Steppe Zone". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 4. doi:10.1017/ehs.2022.16. ISSN 2513-843X.

- Higham, Thomas F.G.; et al. (2019). "A new chronology for a prehistoric copper production centre in central Thailand using kernel density estimates". Antiquity. preprint p. 4 – via ora.ox.ac.uk.

... tin-bronze-using metalworkers of the Seima-Turbino horizon (c. 2300–1700 BC), whose origins lie in the Altaï Mountain district of western Mongolia and which spread west and east across northern Eurasia ...

Higham, Thomas F.G.; et al. (August 2020). "A prehistoric copper-production centre in central Thailand: Its dating and wider implications". Antiquity. 94 (376): 950. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.120. S2CID 225433500. - Marchenko et al. 2017.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 447.

- Keys, David (January 2009). "Scholars crack the code of an ancient enigma". BBC History Magazine. Vol. 10, no. 1. p. 9.

- Kang, In Uk (May 2020). Archaeological perspectives on the early relations of the Korean peninsula with the Eurasian steppe (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. p. 34 – via sino-platonic.org.

-

Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert, eds. (6 May 2002) [1 January 1999]. A Dictionary of Archaeology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 517. ISBN 978-0-631-23583-5.

1999 ed.: Blackwell Publishers doi:10.1002/9780470753446 ISBN 978-0-470-75344-6 - Anthony 2007.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 443–444.

- Chernykh 1992, figs. 74 & 75, pp. 220–221.

- Chernykh, E.N. (2008). "Formation of the Eurasian "steppe belt" of stockbreeding cultures". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 35 (3): 36–53. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2008.11.003.

- Frachetti, Michael David. Pastoralist Landscapes and Social Interaction in Bronze Age Eurasia. pp. 52–53.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 444–447.

- Higham, C.; Higham, T.; Kijngam, A. (2011). "Cutting a Gordian knot: The Bronze Age of southeast Asia: Origins, timing and impact". Antiquity. 85 (328): 583–598. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067971. S2CID 163064575.

- Chernykh, E.N. (2008). "The "steppe belt" of stockbreeding cultures in Eurasia during the early Metal Age". Trab. Prehist. 65: 73–93. doi:10.3989/tp.2008.08004.

- Sarkissian, Clio Der; Balanovsky, Oleg; Brandt, Guido; Khartanovich, Valery; Buzhilova, Alexandra; Koshel, Sergey; et al. (14 February 2013). "Ancient DNA reveals prehistoric gene-flow from Siberia in the complex human population history of north east Europe". PLOS Genetics. 9 (2): e1003296. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003296. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 3573127. PMID 23459685.

- Illumäe; et al. (2016). "Human Y chromosome haplogroup N: A non-trivial time-resolved phylogeography that cuts across language families". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 99 (1): 163–173. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.025. PMC 5005449. S2CID 20536258.

- "Haplogroup N". YTree. yfull.com/tree (v8.09.00 ed.). Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Childebayeva, Ainash; et al. (October 1, 2023). "Bronze Age Northern Eurasian Genetics in the Context of Development of Metallurgy and Siberian Ancestry". BioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2023.10.01.560195.

Sources

- Christian, David (1998). A History of Russia, Central Asia, and Mongolia. ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world.

- Marchenko, Z.V.; Svyatko, S.V.; Molodin, V.I.; Grishin, A.E.; Rykun, M.P. (Oct 2017). "Radiocarbon chronology of complexes with Seima-Turbino type objects (Bronze Age) in southwestern Siberia" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 59 (5): 1381–1397. Bibcode:2017Radcb..59.1381M. doi:10.1017/RDC.2017.24. S2CID 133742189 – via pureadmin.qub.ac.uk.

- Chernykh, Evgenil Nikolaevich (1992). Ancient Metallurgy in the USSR: The Early Metal Age. New Studies in Archaeology. Translated by Wright, Sarah. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780-521-25257-7.