History of Southeast Asia

The history of Southeast Asia covers the people of Southeast Asia from prehistory to the present in two distinct sub-regions: Mainland Southeast Asia (or Indochina) and Maritime Southeast Asia (or Insular Southeast Asia). Mainland Southeast Asia comprises Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar (or Burma), Peninsular Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam whereas Maritime Southeast Asia comprises Brunei, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Christmas Island, East Malaysia, East Timor, Indonesia, Philippines and Singapore.[1][2]

| History of Southeast Asia |

|---|

|

| Prehistory of Southeast Asia |

| Indianised and Buddhist kingdoms |

| Decline of Hindu/Buddhist influence and sea trade |

| European colonialism |

| World War II and decolonisation |

| Cold War |

| Contemporary Southeast Asia |

The earliest Homo sapiens presence in Mainland Southeast Asia can be traced back to 70,000 years ago and to at least 50,000 years ago in Maritime Southeast Asia. Since 25,000 years ago, East Asian-related (Basal East Asian) groups expanded southwards into Maritime Southeast Asia from Mainland Southeast Asia.[3][4] As early as 10,000 years ago, Hoabinhian settlers from Mainland Southeast Asia had developed a tradition and culture of distinct artefact and tool production. During the Neolithic, Austroasiatic peoples populated Indochina via land routes, and sea-borne Austronesian immigrants preferably settled in Maritime Southeast Asia. The earliest agricultural societies that cultivated millet and wet-rice emerged around 1700 BCE in the lowlands and river floodplains of Indochina.[5]

The Phung Nguyen culture (modern northern Vietnam) and the Ban Chiang site (modern Thailand) account for the earliest use of copper by around 2,000 BCE, followed by the Dong Son culture, which by around 500 BCE had developed a highly sophisticated industry of bronze production and processing. Around the same time, the first Agrarian Kingdoms emerged where territory was abundant and favourable, such as Funan at the lower Mekong and Van Lang in the Red River delta.[6] Smaller and insular principalities increasingly engaged in and contributed to the rapidly expanding sea trade.

The wide topographical diversity of Southeast Asia has greatly influenced its history. For instance, Mainland Southeast Asia with its continuous but rugged and difficult terrain provided the basis for the early Cham, Khmer, and Mon civilizations. The sub-region's extensive coastline and major river systems of the Irrawaddy, Salween, Chao Phraya, Mekong and Red River have directed socio-cultural and economic activities towards the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.[7][8]

In Maritime Southeast Asia, apart from exceptions such as Borneo and Sumatra, the patchwork of recurring land-sea patterns on widely dispersed islands and archipelagos admitted moderately sized thalassocratic states indifferent to territorial ambitions, where growth and prosperity were associated with sea trade.[9] Since around 100 BCE, Maritime Southeast Asia has occupied a central position at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea trading routes, immensely stimulating its economy and influencing its culture and society. Most local trading polities selectively adopted Indian Hindu elements of statecraft, religion, culture and administration during the early centuries of the common era, which marked the beginning of recorded history in the area and the continuation of a characteristic cultural development. Chinese culture diffused into the region more indirectly and sporadically, as trade was mostly based on land routes like the Silk Road. Long periods of Chinese isolationism and political relations that were confined to ritualistic tribute procedures prevented deep acculturation.[10]

Buddhism, particularly in Indochina, began to affect political structures beginning in the 8th to 9th centuries CE. Islamic ideas arrived in insular Southeast Asia as early as the 8th century, and the first Muslim societies in the area emerged by the 13th century.[11][12][13] The era of European colonialism, early Modernity and the Cold War era revealed the reality of limited political significance for the various Southeast Asian polities. Post-World War II national survival and progress required a modern state and a strong national identity.[14] Most modern Southeast Asian countries enjoy a historically unprecedented degree of political freedom and self-determination and have embraced the practical concept of intergovernmental co-operation within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[15][16]

Name

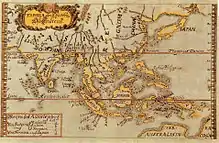

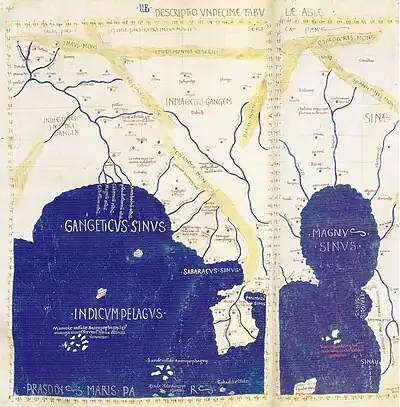

Though there are numerous ancient historic Asian designations for Southeast Asia, none are geographically consistent with each other. Names referring to Southeast Asia include Suvarnabhumi or Sovannah Phoum (Golden Land) and Suvarnadvipa (Golden Islands) in Indian tradition, the Lands below the Winds[17] in Arabia and Persia, Nanyang (Chinese: 南洋; lit. 'South Ocean') in China and Nan’yō (南洋) in Japan.[18] A 2nd-century world map created by Ptolemy of Alexandria names the Malay Peninsula as Chersonesus Aurea (lit. 'Golden Peninsula').[19]

The term "Southeast Asia" was first used in 1839 by American pastor Howard Malcolm in his book Travels in South-Eastern Asia. Malcolm only included the Mainland section and excluded the Maritime section in his definition of Southeast Asia.[20] The term was officially used to designate the area of operation (the South East Asia Command, SEAC) for Anglo-American forces in the Pacific Theater of World War II from 1941 to 1945.[21]

| Part of a series on |

| Human history Human Era |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Prehistory

Paleolithic

The region was already inhabited by Homo erectus from approximately 1,500,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene age.[22] Data analysis of stone tool assemblages and fossil discoveries from Indonesia, Southern China, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and more recently Cambodia[23] and Malaysia[24] has established Homo erectus migration routes and episodes of presence as early as 120,000 years ago, with even older isolated finds dating back to 1.8 million years ago.[25][26] Java Man (Homo erectus erectus) and Homo floresiensis attest to a sustained regional presence and isolation, long enough for notable diversification of the species' specifics. Rock art (parietal art) dating from 40,000 years ago (which is currently the world's oldest) has been discovered in the caves of Borneo.[27] Homo floresiensis also lived in the area up until at least 50,000 years ago, after which they became extinct.[28] Distinct Homo sapiens groups, ancestral to East-Eurasian (East Asian-related) populations, and South-Eurasian (Papuan-related) populations, reached the region by 50,000 BCE to 70,000 BCE, with some arguing earlier.[3][29][30] These immigrants might have, to some extent, merged and reproduced with members of the archaic population of Homo erectus, as the fossil discoveries in the Tam Pa Ling Cave suggest.[31] During much of this time the present-day islands of western Indonesia were joined into a single landmass known as Sundaland due to lower sea levels.

Ancient remains of hunter-gatherers in Maritime Southeast Asia, such as one Holocene hunter-gatherer from cave of Leang Panninge in South Sulawesi, had ancestry from both the South-Eurasian lineage (represented by Papuans and Aboriginal Australians), and the East-Eurasian lineage (represented by East Asians). The hunter-gatherer individual had approximately 50% "Basal-East Asian" ancestry and was positioned in between modern East Asians and Papuans of Oceania. The authors writing about the individual concluded that East Asian-related ancestry expanded from Mainland Southeast Asia into Maritime Southeast Asia much earlier than previously suggested, as early as 25,000 BCE, long before the expansion of Austroasiatic and Austronesian groups.[33]

Distinctive Basal-East Asian (East-Eurasian) ancestry was recently found to have originated in Mainland Southeast Asia at ~50,000 BCE, and expanded through multiple migration waves southwards and northwards respectively. Geneflow of East-Eurasian ancestry into Maritime Southeast Asia and Oceania is estimated to ~25,000 BCE (possibly as early as 50,000 BCE). The pre-Neolithic South-Eurasian populations of Maritime Southeast Asia were largely replaced by the expansion of various East-Eurasian populations, beginning about 25,000 BCE from Mainland Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia was dominated by East Asian-related ancestry already in 15,000 BCE, predating the expansion of Austroasiatic and Austronesian peoples.[3]

Ocean drops of up to 120 m (393.70 ft) below the present level during Pleistocene glacial periods revealed the vast lowlands known as Sundaland, enabling hunter-gatherer populations to freely access insular Southeast Asia via extensive terrestrial corridors. Modern human presence in the Niah cave on East Malaysia dates back to 40,000 years BP, although archaeological documentation of the early settlement period suggests only brief occupation phases.[34] However, author Charles Higham argues that despite glacial periods, modern humans were able to cross the sea barrier beyond Java and Timor, who around 45,000 years ago left traces in the Ivane Valley in eastern New Guinea "at an altitude of 2,000 m (6,561.68 ft) exploiting yams and pandanus, hunting and making stone tools between 43,000 and 49,000 years ago."[35]

The oldest habitation discovered in the Philippines is located at the Tabon Caves and dates back to approximately 50,000 years BP. Items found there such as burial jars, earthenware, jade ornaments and other jewellery, stone tools, animal bones and human fossils date back to 47,000 years BP. Unearthed human remains are approximately 24,000 years old.[36]

Signs of an early tradition are discernible in the Hoabinhian, the name given to an industry and cultural continuity of stone tools and flaked cobble artefacts that appear around 10,000 BP in caves and rock shelters first described in Hòa Bình, Vietnam, and later documented in Terengganu, Malaysia, Sumatra, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia and Yunnan, southern China. Research emphasises considerable variations in quality and nature of the artefacts, influenced by region-specific environmental conditions and proximity and access to local resources. The Hoabinhian culture accounts for the first verified ritual burials in Southeast Asia.[37][38]

Neolithic migrations

The Neolithic was characterized by several migrations into Mainland and Island Southeast Asia from southern China by Austronesian, Austroasiatic, Kra-Dai and Hmong-Mien-speakers.[40]

The most widespread migration event was the Austronesian expansion, which began around 5,500 BP (3,500 BCE) from Taiwan and coastal southern China. Due to their early invention of ocean-going outrigger boats and voyaging catamarans, Austronesians rapidly colonized Island Southeast Asia, before spreading further into Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, Madagascar and the Comoros. They dominated the lowlands and coasts of Island Southeast Asia, intermarrying with the indigenous Negrito and Papuan peoples to varying degrees, giving rise to modern Islander Southeast Asians, Micronesians, Polynesians, Melanesians and Malagasy.[42][43][44][45]

The Austroasiatic migration wave involved the Mon and Khmer peoples and migrated to the broad riverine floodplains of Burma, Indochina and Malaysia.[46]

Early agricultural societies

.png.webp)

Territorial principalities in both Insular and Mainland Southeast Asia, characterised as Agrarian kingdoms,[48] developed an economy by around 500 BCE based on surplus crop cultivation and moderate coastal trade of domestic natural products. Several states of the Malayan-Indonesian "thalassian" zone[49] shared these characteristics with Indochinese polities like the Pyu city-states in the Irrawaddy River valley, the Văn Lang kingdom in the Red River delta and Funan around the lower Mekong.[6] Văn Lang, founded in the 7th century BCE, endured until 258 BCE under the Hồng Bàng dynasty, as part of the Đông Sơn culture that sustained a dense and organised population that produced an elaborate Bronze Age industry.[50][51]

Intensive wet-rice cultivation in an ideal climate enabled the farming communities to produce a regular crop surplus that was used by the ruling elite to raise, command and pay work forces for public construction and maintenance projects such as canals and fortifications.[50][49]

Though millet and rice cultivation was introduced around 2000 BCE, hunting and gathering remained an important aspect of food provision, in particular in forested and mountainous inland areas. Many tribal communities of the aboriginal Australo-Melanesian settlers continued a lifestyle of mixed sustenance until the modern era.[52] Many areas in Southeast Asia participated in the Maritime Jade Road, a diverse sea-based trade network which functioned for 3,000 years, mostly in Southeast Asia, between 2000 BCE to 1000 CE.[53][54][55][56]

Bronze Age Southeast Asia

The earliest known evidence of copper and bronze production in Southeast Asia was found at Ban Chiang in north-east Thailand and among the Phùng Nguyên culture of northern Vietnam around 2000 BCE.[57]

The Đông Sơn culture established a tradition of bronze production and the manufacture of evermore refined bronze and iron objects, such as plows, axes and sickles with shaft holes, socketed arrows and spearheads and small ornamented items.[58] By about 500 BCE, large and delicately decorated bronze drums of remarkable quality, weighing more than 70 kg (150 lb), were produced in the laborious lost-wax casting process. This industry of highly sophisticated metal processing was developed independent of Chinese or Indian influence. Historians relate these achievements to the presence of well-organised, centralised and hierarchical communities and a large population.[59]

Pottery culture

Between 1000 BCE and 100 CE, the Sa Huỳnh culture flourished along the south-central coast of Vietnam.[60] Ceramic jar burial sites that included grave goods have been discovered at various sites along the entire territory. Among large, thin-walled terracotta jars, ornamented and colourised cooking pots, glass items, jade earrings and metal objects were deposited near the rivers and along the coast.[61]

The Buni culture is the name given to another early independent centre of refined pottery production that has been well documented on the basis of excavated burial gifts, deposited between 400 BCE and 100 CE in coastal north-western Java.[62] The objects and artefacts of the Buni tradition are known for their originality and remarkable quality of incised and geometric decors.[63] Its resemblance to the Sa Huỳnh culture and the fact that it represents the earliest Indian Rouletted Ware recorded in Southeast Asia are subjects of ongoing research.[64]

Early historical era

Austronesian maritime trade network

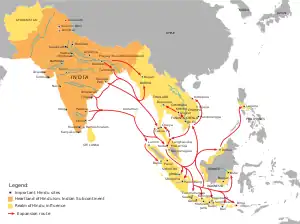

The first true maritime trade network in the Indian Ocean was the Austronesian maritime trade network initiated by the Austronesian peoples of Island Southeast Asia.[65] They established trade routes with Southern India and Sri Lanka as early as 1500 BCE, exchanging material culture (like catamarans, outrigger boats, sewn-plank boats and paan) and cultigens (like coconuts, sandalwood, bananas and sugarcane). The trade network also connected the material cultures of India and China, as well as constituting the majority of the Indian Ocean component of the spice trade. Indonesians in particular were trading in spices (mainly cinnamon and cassia) with East Africa using catamarans and outrigger boats and sailing with the help of the Westerlies in the Indian Ocean. This trade network expanded to reach as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar by 500 CE. It continued through historic times, later becoming the Maritime Silk Road.[65][66][67][68][69] This trade network also included smaller trade routes within Island Southeast Asia, including the lingling-o jade and trepanging networks.

In eastern Austronesia, various traditional maritime trade networks also existed. Among them were the ancient Lapita trade network of Island Melanesia;[70] the Hiri trade cycle, Sepik Coast exchange and Kula ring of Papua New Guinea;[70] the ancient trading voyages in Micronesia between the Mariana Islands and the Caroline Islands (and possibly also New Guinea and the Philippines);[71] and the vast inter-island trade networks of Polynesia.[72]

Indianised kingdoms

By around 500 BCE, Asia's expanding land and maritime trade led to socio-economic and cultural stimulation and diffusion of mainly Hindu beliefs into the regional cosmology of Southeast Asia.[73] Iron Age trade expansion also caused regional geostrategic remodelling. Southeast Asia was now situated at the convergence of the Indian and the East Asian maritime trade routes, a basis for economic and cultural growth. The concept of "Indianised kingdoms", a term coined by French scholar George Cœdès, describes how Southeast Asian principalities incorporated central aspects of Indian institutions, religion, statecraft, administration, culture, epigraphy, writing and architecture.[74][75]

The earliest Hindu kingdoms emerged in Sumatra and Java, followed by mainland polities such as Funan and Champa. Selective adoption of Indian sociocultural elements stimulated the emergence of centralised states and development of highly organised societies. Local leaders began to adopt Hindu worship into state religion, using the Hindu concept of devarāja to reinforce divine rule (as opposed to the Chinese concept of Mandate of Heaven).[76][77][78]

The exact nature, process and extent of Indian influence upon the civilizations of the region is still fiercely debated by contemporary scholars. One such debate is over the extent to which Indian merchants, Brahmins, nobles or Southeast Asian mariner-merchants played central roles in bringing Indian conceptions to Southeast Asia. Additionally, the depth of the influence of Indian traditions is still contested. Whereas early 20th-century scholars emphasized the thorough Indianisation of Southeast Asia, more recent authors have argued that Indian influence was much more limited, affecting only a small section of the elite.[79][80]

Maritime trade from China to India passed Champa and Funan at the Mekong Delta, proceeded along the coast to the Isthmus of Kra, portaged across the narrow and transhipped for distribution in India. This trading link boosted the development of Funan, its successor Chenla and the Malayan states of Langkasuka on the eastern coast and Kedah on the western.

Numerous coastal communities in maritime Southeast Asia adopted Hindu and Buddhist cultural and religious elements from India and developed complex polities ruled by native dynasties. Early Hindu kingdoms in Indonesia include the 4th-century Kutai that rose in East Kalimantan, Tarumanagara in West Java and Kalingga in Central Java.[81]

Early relations with China

The earliest attested trading contacts in Southeast Asia were with the Chinese Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), when cowry shells served as currency. During the Zhou dynasty (1050–771 BCE), various natural products, such as ivory, rhinoceros horn, tortoise shells, pearls and birds' feathers found their way to Luoyang, the Zhou capital. Although current knowledge about port localities and shipping lanes is very limited, it is assumed that most of this exchange took place on land routes, and only a small percentage was shipped "on coastal vessels crewed by Malay and Yue traders".[82]

Military conquests during the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) brought a number of foreign peoples within the Chinese empire when the Imperial Chinese tributary system began to evolve under Han rule. This tributary system was based on the Chinese worldview that had developed under the Shang dynasty, in which China was deemed the center and apogee of culture and civilization, the "Middle kingdom" (Mandarin: 中国, Zhōngguó), surrounded by several layers of increasingly barbarous peoples.[83] Contact with Southeast Asia steadily increased by the end of the Han period.[82]

Between the 2nd-century BCE and 15th-century CE, the Maritime Silk Road flourished, connecting China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian peninsula, Somalia and all the way to Egypt and Europe.[84] Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia and by Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea.[85]

The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Austronesian spice trade networks of Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India (established 1000–600 BCE), as well as the jade industry trade in lingling-o artifacts from the Philippines in the South China Sea (c. 500 BCE).[86][67] For most of its history, Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the Strait of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay peninsula and the Mekong delta (although Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to the Indianization of these regions). Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, although Tamil and Persian traders also sailed them.[85] The route was influential in the early spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the East.[87]

China later built its own fleets starting from the Song dynasty in the 10th century, participating directly in the trade route up until the end of the Colonial Era and the collapse of the Qing dynasty.[85]

Spread of Buddhism

Local rulers benefited from the introduction of Hinduism during the early common era, using it to greatly enhance the legitimacy of their reign as devarāja. Historians increasingly argue that the process of Hindu religious diffusion in the region must be attributed to the initiative of the local chieftains. Buddhist teachings, which almost simultaneously arrived in Southeast Asia, developed during the subsequent centuries, gaining more appeal among the general population. In the 3rd century BCE, the Buddhist Indian Emperor Ashoka initiated missionary efforts to send trained monks and missionaries abroad to proselytise Buddhism, including its sizeable body of literature, oral traditions, iconography and art. To missionaries used Buddhist teachings to offer guidance in central existential questions, placing an emphasis on individual effort and conduct.[88][89][90]

Between the 5th and the 13th century CE, Buddhism flourished in Southeast Asia. By the 8th century, the Buddhist Srivijaya kingdom based in Sumatra emerged as a major trading power in central Maritime Southeast Asia. Around the same period, the Shailendra dynasty of Java extensively promoted Buddhist art that found its strongest expression in the vast Borobudur temple.[91] Following the establishment of the Khmer Empire in Cambodia, the first Buddhist kings of Mainland Southeast Asia emerged during the 11th century.[92] Mahayana Buddhism took hold first in Southeast Asia, as the original Theravada Buddhism had fallen out of favor India centuries before reaching the region. However, a pure form of Theravada Buddhist teachings had been preserved in Sri Lanka since the 3rd century. Pilgrims and wandering monks from Sri Lanka introduced Theravada Buddhism in the Pagan Empire of Burma, the Sukhothai Kingdom in northern Thailand and Laos, the Lower Mekong Basin during Cambodia's dark ages and further into Vietnam and Maritime Southeast Asia.[93]

Medieval period

_VI_(1070423631).jpg.webp)

In Maritime Southeast Asia, the Srivijaya kingdom on Sumatra developed into the dominant power by the 5th century CE. Its capital Palembang became a major seaport and functioned as an entrepôt on the Spice Route between India and China. Srivijaya was also a notable center of Vajrayāna Buddhist learning and influence.[94] Around the 6th century CE, Malay merchants began sailing to Srivijaya, where goods were transported directly in Sumatran ports. The winds of the Northeast Monsoon during October to December prevented sailing ships from proceeding directly from the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea, as did the Southwest Monsoon during July to September, forcing trade routes to pass through Srivijaya. However, the kingdom's wealth and influence began to fade when advancements in nautical technology in the 10th century enabled Chinese and Indian merchants to ship cargo directly between their countries. These advancements also aided the Chola dynasty of Tamilakam, Southern India, in carrying out a series of destructive attacks on Srivijaya, effectively ending Palembang's entrepôt position in the Indo-Chinese trade route. As the influence of the Srivijaya kingdom faded by about the 13th century, Sumatra came to be ruled by a kaleidoscope of Buddhist kingdoms for the next two centuries, including the Malayu, Pannai, and Dharmasraya kingdoms.

To the southeast of Sumatra, West Java was ruled by the Hindu Sunda Kingdom (c. 669–1579) after the fall of the Tarumanagara, while Central and East Java were dominated by a myriad of competing agrarian kingdoms including the Shailendra dynasty (c. 650–1000), Mataram Kingdom (c. 716–1016), Kediri Kingdom (c. 1042–1222), Singhasari (1222–1292), and Majapahit (c. 1293–1500). In the 8th and 9th centuries, the Sailendra dynasty that ruled the Mataram kingdom built a number of massive monuments in Central Java, including the Sewu and Borobudur Buddhist temples. According to the Nagarakṛtāgama, an Old Javanese poem from around the 13th century, vassal states of the Majapahit Empire spread throughout much of today's Indonesia, making it possibly the largest empire ever to exist in Southeast Asia. The empire declined in the 15th century after the rise of Islamic states in coastal Java, the Malay peninsula, and Sumatra.

In the Philippines, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription dating from 900 CE is the earliest known calendar-dated document from the islands. It relates a debt granted from a maginoo (royalty) who lived in the Tagalog city-state of Tondo which is now part of Manila area. The document mentions several contemporary states in the area, including Mataram Kingdom in Java.

The Khmer Empire covered much of mainland Southeast Asia from the early 9th until the 15th century, during which time a sophisticated architecture was developed, exemplified in the structures of the capital city Angkor. Situated in modern-day Vietnam, the kingdoms of Đại Việt and Champa were rivals to the Khmer Empire in the region. The Mon kingdom of Dvaravati was another major regional presence, first appearing in records around the 6th century CE. By the 10th century, however, Dvaravati had come under the influence of the Khmer. Nearby, Thai tribes conquered the Chao Phraya River valley of modern-day central Thailand around the 12th century and established the Sukhothai Kingdom in the 13th century and the Ayutthaya Kingdom in the 14th century.[95][96]

By the mid-16th century, the Burmese First Toungoo Empire was one of the largest, strongest and richest empires in Southeast Asia.[97][98] At its peak, it was the dominant power in mainland Southeast Asia, exercising "suzerainty from Manipur to the Cambodian marches and from the borders of Arakan to Yunnan".[99] The empire included Mon and Shan states and annexed territories in the Kingdom of Lan Na, Kingdom of Laos, and the Ayutthaya kingdom.[100][101] Early European accounts describe the lower part of the Toungoo Empire as having possessed 3–4 excellent ports that facilitated considerable trade in a variety of goods.[102] The empire supplied the port of Malacca with rice and other foodstuffs, along with luxury goods such as rubies, sapphires, musk, lac, benzoin, and gold to trade. In return, the lower part of the empire imported Chinese manufactures and Indonesian spices through its ports. Additionally, merchants from West Asia and India exchanged large quantities of Indian textiles for Burmese luxury products and eastern goods. The arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century further strengthened the empire's position, both commercially and militarily.[103]

Spread of Islam

By the 8th century CE, less than 200 years after the establishment of Islam in Arabia, the first Islamic traders and merchants who adhered to Mohammad's prophecies began to appear in maritime Southeast Asia. However, Islam did not play a notable role anywhere in mainland Southeast Asia until the 13th century.[104][105][106] Instead, widespread and gradual replacement of Hinduism by Theravāda Buddhism reflected a shift to a more personal, introverted spirituality acquired through individual ritual activities and effort.

In addressing the issue of how Islam was introduced into Southeast Asia, historians have elaborated various routes from Arabia to India and then from India to Southeast Asia. Of these, two seem to take prominence: either Arabian traders and scholars who did not live or settle in India spread Islam directly to maritime Southeast Asia, or Arab traders that had been settling in coastal India and Sri Lanka for generations did. Muslim traders from India (Gujarat) and converts of South Asian descent are variously considered to play a major role.[107][108]

A number of sources propose the South China Sea as another route of Islamic introduction to Southeast Asia. Arguments for this hypothesis include the following:

- Extensive trade between Arabia and China before the 10th century is well documented and has been corroborated by archaeological evidence (see, for example, Belitung shipwreck).[109][110]

- During the Mongol conquest and the subsequent rule of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), hundreds of thousands of Muslims entered China. In Yunnan, Islam was propagated and commonly embraced.[111]

- Kufic grave stones in Champa, modern-day Vietnam, are indices of an early and permanent Islamic community in mainland Southeast Asia.[112][113][114]

- The founder of the Demak Sultanate in Java was of Sino-Javanese origin.[115][116]

- Hui mariner Zheng He proposed ancient Chinese architecture as the stylistic basis for the oldest Javanese mosques during his 15th-century visit to Demak, Banten, and the Red Mosque of Panjunan in Cirebon, West Java.[104]

In 2013, the European Union published the European Commission Forum, which maintains an inclusive attitude on the matter:[117]

Islam spread in Southeast Asia via Muslims of diverse ethnic and cultural origins, from Middle Easterners, Arabs and Persians, to Indians and even Chinese, all of whom followed the great commercial routes of the epoch.

Unlike in other Islamic regions, Islam developed in Southeast Asia in a distinctly syncretic manner that allowed the continuation and inclusion of elements and ritual practices of Hinduism, Buddhism and ancient Pan-East Asian animism. Most principalities developed highly distinctive cultures as a result of centuries of active participation in cultural exchange situated at the cross-roads of the Maritime Silk Road coming from across the Indian Ocean in the West and the South China Sea in the East. Cultural and institutional adoption was a creative and selective process, in which foreign elements were incorporated into a local synthesis.[118] Unlike some other "Islamised" regions like North Africa, Iberia, the Middle East and later northern India, Islamic faith in Southeast Asia was not enforced in the wake of territorial conquests, but because of trade routes. In this way, the Islamisation of Southeast Asia is more akin to that of Turkic Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, southern India and northwest China.

There are various records of lay Muslim missionaries, scholars and mystics, particularly Sufis, who were active in peacefully proselytizing in Southeast Asia. Java, for example, received Islam by nine men, referred to as the "Wali Sanga" or "Nine Saints," although the historical identity of such people is almost impossible to determine. The foundation of the first Islamic kingdom in Sumatra, the Samudera Pasai Sultanate, took place during the 13th century.

The conversion of the remnants of the Buddhist Srivijaya empire that once controlled trade in much of Southeast Asia, in particular the Strait of Malacca, marked a religious turning point with the conversion of the strait into an Islamic water. With the fall of Srivijaya, the way was open for effective and widespread proselytization and the establishment of Muslim trading centers. Many modern Malays view the Sultanate of Malacca, which existed from the 15th to the early 16th century, as the first political entity of contemporary Malaysia.[119]

The idea of equality before God for the Ummah (the people of God) and a personal religious effort through regular prayer in Islam could have been more appealing than a perceived fatalism in Hinduism at the time.[120] However, Islam also taught obedience and submission, which could have helped guarantee that the social structure of a converted people or political entity saw less fundamental changes.[82]

Islam and its notion of exclusivity and finality is seemingly incompatible with other religions, including the Chinese concept of heavenly harmony and the Son of Heaven as its enforcer. The integration of the traditional East Asian tributary system with China at the centre Muslim Malays and Indonesians exacted a pragmatic approach of cultural Islam in diplomatic relations with China.[82]

Chinese treasure voyages

By the end of the 14th century, Ming China had conquered Yunnan in the South, yet it had lost control of the Silk Road after the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty. The ruling Yongle Emperor resolved to focus on the Indian Ocean sea routes, seeking to consolidate the ancient Imperial Tributary System, establish greater diplomatic and military presence, and widen the Chinese sphere of influence. He ordered the construction of a huge trade and representation fleet that, between 1405 and 1433, undertook several voyages into Southeast Asia, India, the Persian Gulf, and as far as East Africa. Under the leadership of Zheng He, hundreds of naval vessels of then unparalleled size, grandeur, and technological advancement and manned by sizeable military contingents, ambassadors, merchants, artists and scholars repeatedly visited major Southeast Asian principalities. The individual fleets engaged in a number of clashes with pirates and occasionally supported various royal contenders. However, pro-expansionist voices at the court in Beijing lost influence after the 1450s, and the voyages were discontinued. The protraction of the ritualistic ceremonies and scanty travels of emissaries in the Tributary System alone was not sufficient to develop firm and lasting Chinese commercial and political influence in the region, especially during the impending onset of highly competitive global trade. During the Chenghua period of the Ming Dynasty, Liu Daxia, who later became the Shangshu of the Ministry of War, hid or burned the archives of Ming treasure voyages.[121][122]

Early modern era

European colonisation

The earliest Europeans to have visited Southeast Asia were Marco Polo during the 13th century in the service of Kublai Khan and Niccolò de' Conti during the early 15th century. Regular and momentous voyages only began in the 16th century after the arrival of the Portuguese, who actively sought direct and competitive trade. They were usually accompanied by missionaries, who hoped to promote Christianity.[123][124]

Portugal was the first European power to establish a bridgehead on the lucrative maritime Southeast Asia trade route, with the conquest of the Sultanate of Malacca in 1511. The Netherlands and Spain followed and soon superseded Portugal as the main European powers in the region. In 1599, Spain began to colonise the Philippines via the Mexico-governed Viceroyalty of New Spain, which the Philippines was territory of. In 1619, acting through the Dutch East India Company, the Dutch took the city of Sunda Kelapa, renamed it Batavia (now Jakarta) as a base for trading and expansion into the other parts of Java and the surrounding territory. In 1641, the Dutch took Malacca from the Portuguese.[note 1] Economic opportunities attracted Overseas Chinese to the region in great numbers. In 1775, the Lanfang Republic, possibly the first republic in the region, was established in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, as a tributary state of the Qing Empire; the republic lasted until 1884, when it fell under Dutch occupation as Qing influence waned.[note 2]

_-_Autor_desconhecido.png.webp)

The British, in the guise of the East India Company led by Josiah Child, had little interest or impact in the region, and were effectively expelled following the Anglo-Siamese War. Britain later turned their attention to the Bay of Bengal following the Peace with France and Spain (1783). During the conflicts, Britain had struggled for naval superiority with the French, and the need of good harbours became evident. Penang Island had been brought to the attention of the Government of India by Francis Light. In 1786, the settlement of George Town was founded at the northeastern tip of Penang Island by Captain Francis Light, under the administration of Sir John Macpherson; this marked the beginning of British expansion into the Malay Peninsula.[125][note 3]

The British also temporarily possessed Dutch territories during the Napoleonic Wars; and Spanish areas in the Seven Years' War. In 1819, Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a key trading post for Britain in their rivalry with the Dutch. However, their rivalry cooled in 1824 when an Anglo-Dutch treaty demarcated their respective interests in Southeast Asia. British rule in Burma began with the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826).

Early United States entry into what was then called the East Indies (usually in reference to the Malay Archipelago) was low key. In 1795, a secret voyage for pepper set sail from Salem, Massachusetts on an 18-month voyage that returned with a bulk cargo of pepper, the first to be so imported into the country, which sold at the extraordinary profit of seven hundred per cent.[126] In 1831, the merchantman Friendship of Salem returned to report the ship had been plundered, and the first officer and two crewmen murdered in Sumatra.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 obligated the Dutch to ensure the safety of shipping and overland trade in and around Aceh, who accordingly sent the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army on the punitive expedition of 1831. President Andrew Jackson also ordered America's first Sumatran punitive expedition of 1832, which was followed by a punitive expedition in 1838. The Friendship incident thus afforded the Dutch a reason to take over Ache; and Jackson, to dispatch diplomatist Edmund Roberts,[127] who in 1833 secured the Roberts Treaty with Siam. In 1856 negotiations for amendment of this treaty, Townsend Harris stated the position of the United States:

The United States does not hold any possessions in the East, nor does it desire any. The form of government forbids the holding of colonies. The United States therefore cannot be an object of jealousy to any Eastern Power. Peaceful commercial relations, which give as well as receive benefits, is what the President wishes to establish with Siam, and such is the object of my mission.[128]

From the end of the 1850s onwards, while the attention of the United States shifted to maintaining their union, the pace of European colonisation shifted to a significantly higher gear. This phenomenon, denoted New Imperialism, saw the conquest of nearly all Southeast Asian territories by the colonial powers. The Dutch East India Company and British East India Company were dissolved by their respective governments, who took over the direct administration of the colonies.

Only Thailand was spared the experience of foreign rule, though Thailand, too, was greatly affected by the power politics of the Western powers. The Monthon reforms of the late 19th Century continuing up till around 1910, imposed a Westernised form of government on the country's partially independent cities called Mueang, such that the country could be said to have successfully colonised itself.[129] Western powers did, however, continue to interfere in both internal and external affairs.[130][131]

By 1913, the British had occupied Burma, Malaya and the northern Borneo territories, the French controlled Indochina, the Dutch ruled the Netherlands East Indies while Portugal managed to hold on to Portuguese Timor. In the Philippines, the 1872 Cavite Mutiny was a precursor to the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898). When the Spanish–American War began in Cuba in 1898, Filipino revolutionaries declared Philippine independence and established the First Philippine Republic the following year. In the Treaty of Paris of 1898 that ended the war with Spain, the United States gained the Philippines and other territories; in refusing to recognise the nascent republic, America effectively reversed her position of 1856. This led directly to the Philippine–American War, in which the First Republic was defeated; wars followed with the Republic of Zamboanga, the Republic of Negros and the Republic of Katagalugan, all of which were also defeated.

Colonial rule had had a profound effect on Southeast Asia. While the colonial powers profited much from the region's vast resources and large market, colonial rule did develop the region to a varying extent. Commercial agriculture, mining and an export based economy developed rapidly during this period. The introduction Christianity bought by the colonist also have profound effect in the societal change.

Increased labour demand resulted in mass immigration, especially from British India and China, which brought about massive demographic change. The institutions for a modern nation state like a state bureaucracy, courts of law, print media and to a smaller extent, modern education, sowed the seeds of the fledgling nationalist movements in the colonial territories. In the inter-war years, these nationalist movements grew and often clashed with the colonial authorities when they demanded self-determination.

20th-century Southeast Asia

Japanese invasion and occupations

In September 1940, following the Fall of France and pursuant to the Pacific war goals of Imperial Japan, the Japanese Imperial Army invaded Vichy French Indochina, which ended in the abortive Japanese coup de main in French Indochina of 9 March 1945. On 5 January 1941, Thailand launched the Franco-Thai War, ended on 9 May 1941 by a Japanese-imposed treaty signed in Tokyo.[132] On 7/8 December, Japan's entry into World War II began with the invasion of Thailand, the only invaded country to maintain nominal independence, due to her political and military alliance with the Japanese—on 10 May 1942, her northwestern Payap Army invaded Burma during the Burma Campaign. From 1941 until war's end, Japanese occupied Cambodia, Malaya and the Philippines, which ended in independence movements. Japanese occupation of the Philippines led to the forming of the Second Philippine Republic, formally dissolved in Tokyo on 17 August 1945. Also on 17 August, a proclamation of Indonesian Independence was read at the conclusion of Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies since March 1942.

Post-war decolonisation

With the rejuvenated nationalist movements in wait, the Europeans returned to a very different Southeast Asia after World War II. Indonesia declared independence on 17 August 1945 and subsequently fought a bitter war against the returning Dutch; the Philippines was granted independence by the United States in 1946; Burma secured their independence from Britain in 1948, and the French were driven from Indochina in 1954 after a bitterly fought war (the Indochina War) against the Vietnamese nationalists. The United Nations provided a forum for nationalism, post-independent self-definition, nation-building and the acquisition of territorial integrity for many newly independent nations.[133]

During the Cold War, countering the threat of communism was a major theme in the decolonisation process. After suppressing the communist insurrection during the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960, Britain granted independence to Malaya and later, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak in 1957 and 1963 respectively within the framework of the Federation of Malaysia. In one of the most bloody single incidents of violence in Cold War Southeast Asia, General Suharto seized power in Indonesia in 1965 and initiated a massacre of approximately 500,000 alleged members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI).

Following the independence of the Indochina states with the battle of Dien Bien Phu, North Vietnamese attempts to conquer South Vietnam resulted in the Vietnam War. The conflict spread to Laos and Cambodia and heavy intervention from the United States. By the war's end in 1975, all these countries were controlled by communist parties. After the communist victory, two wars between communist states—the Cambodian–Vietnamese War of 1975–89 and the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979—were fought in the region. The victory of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia resulted in the Cambodian genocide.[134][135]

In 1975, Portuguese rule ended in East Timor. However, independence was short-lived as Indonesia annexed the territory soon after. However, after more than 20 years of fighting Indonesia, East Timor won its independence and was recognised by the UN in 2002. Finally, Britain ended its protectorate of the Sultanate of Brunei in 1984, marking the end of European rule in Southeast Asia.

Contemporary Southeast Asia

Modern Southeast Asia has been characterised by high economic growth by most countries and closer regional integration. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand have traditionally experienced high growth and are commonly recognised as the more developed countries of the region. As of late, Vietnam too had been experiencing an economic boom. However, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and the newly independent East Timor are still lagging economically.

On 8 August 1967, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was founded by Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines. Since Cambodian admission into the union in 1999, East Timor is the only Southeast Asian country that is not part of ASEAN, although plans are under way for eventual membership. The association aims to enhance co-operation among Southeast Asian community. ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established to encourage greater trade among ASEAN members. ASEAN has also been a front runner in greater integration of Asia-Pacific region through East Asia Summits.

See also

- Buddhism in Southeast Asia

- Hinduism in Southeast Asia

- Islam in Southeast Asia

- Greater India

- Two Layer hypothesis

- Spratly Islands

- History of Brunei

- History of Cambodia

- History of East Timor

- History of Indonesia

- History of Laos

- History of Malaysia

- History of Myanmar

- History of the Philippines

- History of Singapore

- History of Thailand

- History of Vietnam

- History of Asia

Notes

- For fifty or sixty years, the Portuguese enjoyed the exclusive trade to China and Japan. In 1717, and again in 1732, the Chinese government offered to make Macao the emporium for all foreign trade, and to receive all duties on imports; but, by a strange infatuation, the Portuguese government refused, and its decline is dated from that period. (Roberts, 2007 PDF image 173 p. 166)

- Other experiments in republicanism in adjacent regions were the Japanese Republic of Ezo (1869) and the Republic of Taiwan (1895).

- Company agent John_Crawfurd used the census taken in 1824 for a statistical analysis of the relative economic prowess of the peoples there, giving special attention to the Chinese: The Chinese amount to 8595, and are landowners, field-labourers, mechanics of almost every description, shopkeepers, and general merchants. They are all from the two provinces of Canton and Fo-kien, and three-fourths of them from the latter. About five-sixths of the whole number are unmarried men, in the prime of life : so that, in fact, the Chinese population, in point of effective labour, may be estimated as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and, as will afterwards be shown, to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000! (Crawfurd image 48. p.30)

References

- Daigorō Chihara (1996). Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10512-6.

- Victor T. King (2008). The Sociology of Southeast Asia: Transformations in a Developing Region. NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-91114-60-1.

- Larena, Maximilian; Sanchez-Quinto, Federico; Sjödin, Per; McKenna, James; Ebeo, Carlo; Reyes, Rebecca; Casel, Ophelia; Huang, Jin-Yuan; Hagada, Kim Pullupul; Guilay, Dennis; Reyes, Jennelyn (30 March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13): e2026132118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (August 2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. hdl:10072/407535. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944. S2CID 237305537.

- Hall, Kenneth R. A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100-1500.

- Carter, Alison Kyra (2010). "Trade and Exchange Networks in Iron Age Cambodia: Preliminary Results from a Compositional Analysis of Glass Beads". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 30. doi:10.7152/bippa.v30i0.9966. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- "Chinese trade" (PDF). Britishmuseum.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Culture, Regionalism and Southeast Asian Identity" (PDF). Amitavacharya.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Willem van Schendel. "Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia 2002 – Willem van Schendel Asia Studies in Amsterdam" (PDF). University of Amsterdam. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- John M. Hobson (2004). The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-54724-6.

- Woodward, Mark (1 September 2009). Juergensmeyer, Mark (ed.). Islamic Societies in Southeast Asia. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195137989.001.0001. ISBN 9780195137989.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Muhamad Ali. Islam in Southeast Asia (Report). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Thongchai Winichakul. "BUDDHISM AND SOCIETY IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN HISTORY" (PDF). University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Constance Wilson. "Colonialism and Nationalism in Southeast Asia". Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- "S-E Asia's identity long in existence". Hartford-hwp com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "SOVEREIGNTY AND THE STATE IN ASIA: THE CHALLENGES OF THE EMERGING INTERNATIONAL ORDER" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Revisiting the "Lands Below the Winds"". Library.ucla.edu. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Kapur; Kamlesh (2010). History of Ancient India (portraits of a Nation), 1/e. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 465. ISBN 978-81-207-4910-8.

- Anna T. N. Bennett (2009). "Gold in early Southeast Asia". ArchéoSciences (33): 99–107. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2072. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Eliot, Joshua; Bickersteth, Jane; Ballard, Sebastian (1996). Indonesia, Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. New York City: Trade & Trade & Travel Publications.

- OOI KEAT GIN. "SOUTHEAST ASIA a Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor 2004" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Bellwood, Peter (10 April 2017). First Islanders: Prehistory and Human Migration in Island Southeast Asia (1 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-119-25154-5.

- "Results of New Research at La‐ang Spean Prehistoric Site" (PDF). dccam org. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Malaysian scientists find stone tools 'oldest in Southeast Asia'". Agence France-Presse. 31 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Swisher 1994; Dennell 2010, p. 262.

- Dennell 2010, p. 266, citing Morwood 2003

- Kiona N. Smith (11/9/2018) What the world’s oldest figurative drawing reveals about human migration

- Morwood, M. J.; Brown, P.; Jatmiko; Sutikna, T.; Wahyu Saptomo, E.; Westaway, K. E.; Rokus Awe Due; Roberts, R. G.; Maeda, T.; Wasisto, S.; Djubiantono, T. (13 October 2005). "Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 437 (7061): 1012–1017. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1012M. doi:10.1038/nature04022. PMID 16229067. S2CID 4302539.

- Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (April 2017). "A Working Model of the Deep Relationships of Diverse Modern Human Genetic Lineages Outside of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (4): 889–902. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 5400393. PMID 28074030.

- "Oldest bones from modern humans in Asia discovered". CBSNews. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Demeter, Fabrice; Shackelford, Laura; Westaway, Kira; Duringer, Philippe; Bacon, Anne-Marie; Ponche, Jean-Luc; Wu, Xiujie; Sayavongkhamdy, Thongsa; Zhao, Jian-Xin; Barnes, Lani; Boyon, Marc; Sichanthongtip, Phonephanh; Sénégas, Frank; Karpoff, Anne-Marie; Patole-Edoumba, Elise; Coppens, Yves; Braga, José; Macchiarelli, Roberto (7 April 2015). "Early Modern Humans and Morphological Variation in Southeast Asia: Fossil Evidence from Tam Pa Ling, Laos". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0121193. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1021193D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121193. PMC 4388508. PMID 25849125.

- Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (August 2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. hdl:10072/407535. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944.

- Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (August 2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. hdl:10072/407535. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944. S2CID 237305537.

The qpGraph analysis confirmed this branching pattern, with the Leang Panninge individual branching off from the Near Oceanian clade after the Denisovan gene flow, although with the most supported topology indicating around 50% of a basal East Asian component contributing to the Leang Panninge genome (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. 7–11).

- Barker, Graeme; Barton, Huw; Bird, Michael; Daly, Patrick; Datan, Ipoi; Dykes, Alan; Farr, Lucy; Gilbertson, David; Harrisson, Barbara; Hunt, Chris; Higham, Tom; Kealhofer, Lisa; Krigbaum, John; Lewis, Helen; McLaren, Sue; Paz, Victor; Pike, Alistair; Piper, Phil; Pyatt, Brian; Rabett, Ryan; Reynolds, Tim; Rose, Jim; Rushworth, Garry; Stephens, Mark; Stringer, Chris; Thompson, Jill; Turney, Chris (March 2007). "The 'human revolution' in lowland tropical Southeast Asia: the antiquity and behavior of anatomically modern humans at Niah Cave (Sarawak, Borneo)". Journal of Human Evolution. 52 (3): 243–261. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.011. PMID 17161859.

- Charles Higham. "Hunter-Gatherers in Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to the Present". Digitalcommons. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "The Tabon Cave Complex and all of Lipuun – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Marwick, B. (2013). "Multiple Optima in Hoabinhian flaked stone artifact palaeoeconomics and palaeoecology at two archaeological sites in Northwest Thailand". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 32 (4): 553–564. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2013.08.004.

- Ji, Xueping; Kuman, Kathleen; Clarke, R.J.; Forestier, Hubert; Li, Yinghua; Ma, Juan; Qiu, Kaiwei; Li, Hao; Wu, Yun (1 December 2015). "The oldest Hoabinhian technocomplex in Asia (43.5 ka) at Xiaodong rockshelter, Yunnan Province, southwest China". Quaternary International. 400: 166–174. Bibcode:2016QuInt.400..166J. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.080. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Simanjuntak, Truman (2017). "The Western Route Migration: A Second Probable Neolithic Diffusion to Indonesia". In Piper, Hirofumi Matsumura and David Bulbeck, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. Vol. 45. ANU Press. ISBN 9781760460952.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume One, Part One. Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-521-66369-4.

- Chambers, Geoffrey K. (2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. American Cancer Society. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01590-2.

- "THE AUSTRONESIAN SETTLEMENT OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA" (PDF). Sealang. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Lipson, Mark; Loh, Po-Ru; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Ko, Ying-Chin; Stoneking, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David (19 August 2014). "Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 5: 4689. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4689L. doi:10.1038/ncomms5689. PMC 4143916. PMID 25137359.

- "Austronesian Southeast Asia: An outline of contemporary issues". Omnivoyage. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- "Origins of Ethnolinguistic Identity in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Roger Blench. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Sidwell, Paul; Blench, Roger (2011). "The Austroasiatic Urheimat: the Southeastern Riverine Hypothesis" (PDF). In Enfield, N.J. (ed.). Dynamics of Human Diversity. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 317–345. ISBN 9780858836389. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Bellwood, Peter (9 December 2011). "The Checkered Prehistory of Rice Movement Southwards as a Domesticated Cereal—from the Yangzi to the Equator" (PDF). Rice. 4 (3–4): 93–103. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9068-9. S2CID 44675525. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- J. Stephen Lansing (2012). Perfect Order: Recognizing Complexity in Bali. Princeton University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-691-15626-2.

- F. Tichelman (2012). The Social Evolution of Indonesia: The Asiatic Mode of Production and Its Legacy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 41. ISBN 978-94-009-8896-5.

- "Pre-Angkorian Settlement Trends in Cambodia's Mekong Delta and the Lower Mekong" (PDF). Anthropology.hawaii.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- "Early Mainland Southeast Asian Landscapes in the First Millennium" (PDF). Anthropology.hawaii.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Hunt, C.O.; Rabett, R.J. (November 2014). "Holocene landscape intervention and plant food production strategies in island and mainland Southeast Asia". Journal of Archaeological Science. 51: 22–33. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.12.011.

- Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan’s relations with the Philippines date back millenia, so it’s a mystery that it’s not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- Higham, Charles; Higham, Thomas; Ciarla, Roberto; Douka, Katerina; Kijngam, Amphan; Rispoli, Fiorella (10 December 2011). "The Origins of the Bronze Age of Southeast Asia". Journal of World Prehistory. 24 (4): 227–274. doi:10.1007/s10963-011-9054-6. S2CID 162300712. Retrieved 11 February 2017 – via Researchgate.net.

- Daryl Worthington (1 October 2015). "How and When the Bronze Age Reached South East Asia". New Historian. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- "history of Southeast Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- John N. Miksic, Geok Yian Goh, Sue O Connor – Rethinking Cultural Resource Management in Southeast Asia 2011 Page 251 "This site dates from the fifth to first century BCE and it is one of the earliest sites of the Sa Huỳnh culture in Thu Bồn Valley (Reinecke et al. 2002, 153–216); 2) Lai Nghi is a prehistoric cemetery richly equipped with iron tools and weapons, ..."

- Ian Glover; Nguyễn Kim Dung. Excavations at Gò Cầm, Quảng Nam, 2000–3: Linyi and the Emergence of the Cham Kingdoms. Academia.edu. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Zahorka, Herwig (2007). The Sunda Kingdoms of West Java, From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with Royal Center of Bogor, Over 1000 Years of Propsperity and Glory. Yayasan cipta Loka Caraka.

- Pierre-Yves Manguin; A. Mani; Geoff Wade (2011). Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 124. ISBN 978-981-4345-10-1.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves and Agustijanto Indrajaya (January 2006). The Archaeology of Batujaya (West Java, Indonesia):an Interim Report, in Uncovering Southeast Asia's past. NUS Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-9971-69-351-0.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Doran, Edwin Jr. (1974). "Outrigger Ages". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 83 (2): 130–140.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Blench, Roger (2004). "Fruits and arboriculture in the Indo-Pacific region". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 24 (The Taipei Papers (Volume 2)): 31–50.

- Friedlaender, Jonathan S. (2007). Genes, Language, & Culture History in the Southwest Pacific. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780195300307.

- Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992). Ancient Chamorro Society. Bess Press. p. 195. ISBN 9781880188057.

- Borrell, Brendan (27 September 2007). "Stone tool reveals lengthy Polynesian voyage". Nature. doi:10.1038/news070924-9. S2CID 161331467.

- Kenneth R. Hal (1985). Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-0843-3.

- National Library of Australia. Asia's French Connection : George Coedes and the Coedes Collection Archived 21 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Southeast Asia: Imagining the region" (PDF). Amitav Acharya. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Craig A. Lockard (2014). Societies, Networks, and Transitions, Volume I: To 1500: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-285-78308-6.

- "The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- Han, Wang; Beisi, Jia (2016). "Urban Morphology of Commercial Port Cities and Shophouses in Southeast Asia". Procedia Engineering. 142: 190–197. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.02.031.

- "Hinduism in Southeast Asia". oxford press. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "Hinduism and Buddhism in Southeast Asia by Monica Sar on Prezi". prezi.com. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Helmut Lukas. "THEORIES OF INDIANIZATION Exemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia)" (PDF). Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "A Short History of China and Southeast Asia.pdf – A Short History of Asia" (PDF). Docs8.minhateca.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Samuel Wells Williams (2006). The Middle Kingdom: A Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts and History of the Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 978-0710311672.

- "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch.

- Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9781588395245.

- Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15. S2CID 140665305.

- Donald K. Swearer. "The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia" (PDF). Suny Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Kitiarsa, Pattana (1 March 2009). "Beyond the Weberian Trails: An Essay on the Anthropology of Southeast Asian Buddhism". Religion Compass. 3 (2): 200–224. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00135.x. ISSN 1749-8171.

- "EXPANSION OF BUDDHISM INTO SOUTHEAST ASIA" (PDF). Unesco. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Miksic, John (22 February 2013). Mysteries of Borobudur Discover Indonesia. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462906994.

- Charles Higham (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- "The Buddhist World: Buddhism in Southeast Asia: Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia". buddhanet.net. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Śrīvijaya towards Chaiya ー The History of Srivijaya". NTT Plala Inc. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Briggs, Lawrence Palmer (1948). "Siamese Attacks On Angkor Before 1430". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 8 (1): 3–33. doi:10.2307/2049480. JSTOR 2049480. S2CID 165680758.

- "A Short History of South East Asia Chapter 3. The Repercussions of the Mongol Conquest of China ...The result was a mass movement of Thai peoples southwards..." (PDF). Stanford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (14 July 2014). Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c. 1580-1760. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-5585-8.

- Lieberman 2003. pp. 151–152.

- Lieberman 2003: 151–152

- "THAI-BURMESE WARFARE DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND THE GROWTH OF THE FIRST TOUNGOO EMPIRE" (PDF). p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "Min-gyi-nyo, the Shan Invasions of Ava (1524-27), and the Beginnings of Expansionary Warfare in Toungoo Burma: 1486-1539" (PDF). pp. 379–382. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c.1580-1760. p. 27.

- Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c. 1580-1760. pp. 27–28.

- Wahby, Ahmed E I (April 2008). "The Architecture of the Early Mosques and Shrines of Java: Influences of the Arab Merchants in the 15th and 16th Centuries?". Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Islam: Islam in Southeast Asia – Dictionary definition of Islam: Islam in Southeast Asia". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Islam, The Spread of Islam To Southeast Asia". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- A History of Islam in the Malay-Indonesian World: between Acculturation and Rigor. Academia.edu. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Introduction to Southeast Asia – The Arrival of Islam in Southeast Asia". Asia Society. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Made in China – National Geographic Magazine". Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Press Room". Asia.si.edu. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "An Earlier Age of Commerce in Southeast Asia : 900–1300 C.E." (PDF). Helsinki.fi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Gravestone – Collections – Antiquities Museum". Antiquities.bibalex.org. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- "Signatures on gravestones: two XII century Iranian tombstones". squarekufic. 18 October 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Tan Ta Sen (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 147. ISBN 978-981-230-837-5.

- Qurtuby, Sumanto Al. "Cheng Ho and the History of Chinese Muslims in Java". Academia.edu. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Tan Ta Sen (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 239. ISBN 978-981-230-837-5.

- "International research update 62" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Bruinessen, Martin van (January 2014). "Ghazwul fikri or Arabisation? Indonesian Muslim responses to globalisation". In: Ken Miichi and Omar Farouk (Eds), Southeast Asian Muslims in the Era of Globalization, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, Pp. 61-85. Academia.edu. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Thompson, Gavin; Lunn, Jon (14 December 2011). Southeast Asia: A political and economic introduction – Commons Library briefing – UK Parliament (Report). Researchbriefings.parliament.uk. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Elder, Joseph W. (July 1966). "Fatalism in India: A Comparison between Hindus and Muslims". Anthropological Quarterly. 39 (3): 227–243. doi:10.2307/3316807. JSTOR 3316807.

- "The Ming Voyages". Columbia University. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Zheng He – Chinese Admiral in the Indian Ocean". Khan Academy. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Thomas Wright. "The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian – Book III" (PDF). Public Library UK. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Niccolò dei Conti". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Crawfurd, John (August 2006) [First published 1830]. "Chapter I – Description of the Settlement.". Journal of an Embassy from the Governor–general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. image 52, p. 34. ISBN 9788120612372. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Trow, Charles Edward (1905). "Introduction". The old shipmasters of Salem. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. xx–xxiii. OCLC 4669778.

When Captain Jonathan Carnes set sail. ...

- Roberts, Edmund (Digitised 12 October 2007) (1837) [1837]. "Introduction". Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: In the U.S. Sloop-of-War Peacock During the Years 1832–34. Harper & Brothers. ISBN 9780608404066. OCLC 12212199.

Having some years since become acquainted with the commerce of Asia and Eastern Africa, the information produced on my mind a conviction that considerable benefit would result from effecting treaties with some of the native powers bordering on the Indian ocean.

- "1b. Harris Treaty of 1856" (exhibition). Royal Gifts from Thailand. National Museum of Natural History. 14 March 2013 [speech delivered 1856]. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Murdoch, John B. (1974). "The 1901–1902 Holy Man's Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. JSS Vol.62.1e (digital): 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

.... Prior to the late nineteenth century reforms of King Chulalongkorn, the territory of the Siamese Kingdom was divided into three administrative categories. First were the inner provinces which were in four classes depending on their distance from Bangkok or the importance of their local ruling houses. Second were the outer provinces, which were situated between the inner provinces and further distant tributary states. Finally there were the tributary states which were on the periphery....

- de Mendonha e Cunha, Helder (1971). "The 1820 Land Concession to the Portuguese" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Society. JSS Vol. 059.2g (digital). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

It was in Ayudhya that Portugal had its first official contact with the Kingdom of Siam, in 1511.

- Oblas, Peter B. (1965). "A Very Small Part of World Affairs" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Society. JSS Vol.53.1e (digital). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

Negotiations 1909–1917. On the 8th of August 1909, Siam's Adviser in Foreign Affairs presented a proposal to the American Minister in Bangkok. The Adviser, Jens Westengard, desired a revision of the existing extraterritorial arrangement of jurisdictional authority. ...

- Vichy versus Asia: The Franco-Siamese War of 1941

- Tom G. Hoogervorst. "Some reflections on Southeast Asia and its position in academia" (PDF). Project Southeast Asia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2009). Genocide and International Justice.

- Olson, James S.; Roberts, Randy (2008). Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam 1945–1995 (5th ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing

Bibliography

- Dennell, Robin (2010). "'Out of Africa I': Current Problems and Future Prospects". In Fleagle, John G.; et al. (eds.). Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 247–74. ISBN 978-90-481-9036-2.

- Morwood, M. J. (2003). "Revised age for Mojokerto 1, an early Homo erectus cranium from East Java, Indonesia". Australian Archaeology. 57: 1–4. doi:10.1080/03122417.2003.11681757. S2CID 55510294. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014..

- Swisher, C. C. (1994). "Age of the earliest known hominin in Java, Indonesia". Science. 263 (5150): 1118–21. Bibcode:1994Sci...263.1118S. doi:10.1126/science.8108729. PMID 8108729.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. pg.123-125

- von Glahn, Richard (27 December 1996). Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000-1700. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91745-3.

- Reid, Anthony (9 May 1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9.

- Sinha, P.C. , ed. Encyclopaedia of South East and Far East Asia (Anmol, 2006).

Further reading

- Reid, Anthony. A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads (Blackwell History of the World, 2015)

- Charles Alfred Fisher (1964). South-east Asia: a social, economic, and political geography. Methuen. ISBN 9789070080600.

- D.G.E. Hall (1981). A History of South-East Asia 4th ed. online version of 1955 edition, 810pp

- Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Lokesh, Chandra, & International Academy of Indian Culture. (2000). Society and culture of Southeast Asia: Continuities and changes. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

- Daigorō Chihara (1996). Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10512-6.

- Peter Church (3 February 2012). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35044-7.

- George Cœdès (1968). The Indianized States of South-East Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Embree, Ainslie T., ed. Encyclopedia of Asian history (1988)

- Bernard Philippe Groslier (1962). The art of Indochina: including Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Crown Publishers.

- Kenneth R. Hall (28 December 2010). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-6762-7.

- Virginia Matheson Hooker (2003). A Short History of Malaysia: Linking East and West. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-955-2.

- Michael C. Howard (23 February 2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Victor T. King (2008). The Sociology of Southeast Asia: Transformations in a Developing Region. NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-91114-60-1.

- Paul Michel Munoz (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. National Book Network. ISBN 978-981-4155-67-0.

- D. R. SarDesai (2003). Southeast Asia, Past and Present. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4143-9.

- Heidhues, Mary Somer. "'Southeast Asia: A Concise History" ISBN 0-500-28303-6

- Majumdar, R.C. (1979). India and South-East Asia. I.S.P.Q.S. History and Archaeology Series Vol. 6. ISBN 978-81-7018-046-3.

- Ooi, Keat Gin, ed. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576077702. Retrieved 24 April 2014.