Selahattin Demirtaş

Selahattin Demirtaş (born 10 April 1973) is a Turkish politician, author,[1] political prisoner[2] and former member of the parliament of Turkey. He was the co-leader of the left-wing pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), serving alongside Figen Yüksekdağ from 2014 to 2018.[3] Selahattin Demirtaş announced that he left politics after the May 2023 elections.[4]

Selahattin Demirtaş | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Chairman of the Peoples' Democratic Party | |

| In office 22 June 2014 – 11 February 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Ertuğrul Kürkçü |

| Succeeded by | Sezai Temelli |

| Co-chair of the Peace and Democracy Party | |

| In office 1 February 2010 – 22 April 2014 | |

| Preceded by | Mustafa Ayzit Demir Çelik |

| Succeeded by | Party abolished See Democratic Regions Party |

| Member of the Grand National Assembly | |

| In office 22 July 2007 – 7 July 2018 | |

| Constituency | Diyarbakır (2007) Hakkari (2011) Istanbul (I) Jun 2015, Nov 2015 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 April 1973 Palu, Elazığ, Turkey |

| Political party | Democratic Society Party (Before 2008) Peace and Democracy Party (2008–2014) Peoples' Democratic Party (2014–2020) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Nurettin Demirtaş (brother) |

| Alma mater | Ankara University |

Demirtaş was the presidential candidate of the HDP in the 2014 presidential election, coming in third place. He led the HDP to gather 13.1% at the June 2015 parliament elections and 10.7% in the snap elections in November 2015, coming 4th in each election. He has been imprisoned since 4 November 2016 and despite his imprisonment the HDP fielded Demirtaş as its candidate for the 2018 presidential election, running his campaign from prison.[5]

In a judgement given in December 2020, the European Court of Human Rights judged that, given "the timing of [Demirtaş] continued detention (coinciding with an important constitutional referendum and the presidential election)" and Turkey's "systemic trend of “gagging” dissenting voices", Demirtaş's continued pre-trial detention's political purpose had been predominant".[6]

Early life and education

Selahattin Demirtaş was born in Palu in 1973, where he completed both his primary and secondary education. From 1991 he studied maritime commerce and management at the Dokuz Eylül University,[7] where he would face political problems that would force him to leave school without finishing his degree. He returned to Diyarbakır and retook the university entrance exam in 1993, after which he enrolled at the Ankara University Law Faculty.[7]

Professional career

After his graduation, Demirtaş worked as a freelance lawyer for a while. In 2000 he became a member of the executive committee at the Diyarbakır branch of the Human Rights Association (IHD).[7] The IHD Chair at the time was Osman Baydemir who was elected as the mayor of Diyarbakır at the following local election. Demirtaş replaced him as the chair of the Diyarbakır IHD in 2004.[7] During his term as chair, the association focused heavily on the increasing unsolved political murders in Turkey.

Early political career

.png.webp)

He cites his experience at the funeral of politician and human right lawyer Vedat Aydın (1953–1991) as a political awakening:

I became a different person. My life's course changed … although I didn't fully understand the reason behind the events, now I knew: we were Kurds, and since this wasn't an identity I would toss away, this was also my problem."[1]

From international observers often dubbed as a Kurdish Obama[8][9] Demirtaş started his political career as a member of the Democratic Society Party (DTP) in 2007 at which time he stood as one of the 'Thousand Hope Candidates' for the DTP and several other democratic organizations in Turkey. He was elected to the 23rd Parliament and became the Parliamentary Chief Officer for the party at the age of 34. As such he supported the abolition of the restrictions against education in the Kurdish language and demanded equal rights for Turks and Kurds in the Turkish constitution.[10] When in October 2007[11] an article published in the Bolu Ekspress demanded politicians of the DTP to be killed for deaths caused by the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) he filed a complaint but the court decided it fell into the bounds of "freedom of thought" in 2008.[12] Demirtaş then appealed to the ECHR for a violation of the 2 and 13 Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights, but in 2015 the ECHR ruled in favor Turkey.[11]

The DTP was closed down by a Supreme Court order in 2009 for the parties alleged connections to the PKK,[13] and the DTP MPs moved to the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP).[14] The BDP held its first congress in 2010 and elected Selahattin Demirtaş and Gültan Kışanak as its new co-chairs. Demirtaş contested the 2011 elections as part of the joint 'Labor, Democracy and Freedom' list endorsed by the BDP and 18 different democratic political organizations, this time for Hakkari. He was re-elected to parliament as an independent.[15]

At a rally in the Kızıltepe district of Mardin in November 2012, Demirtaş criticized the Turkish police for intervening after marchers carried posters of Abdullah Öcalan, saying "I call on you, those who are not bothered about the Kurds’ killer Evren’s statue being erected [or by] schools named after Evren. If they [Kurds] cannot hang Öcalan’s poster in Kurdistan, then where would they hang it? We will go further and erect his statue."[16][17] In 2019, Demirtaş defended his statement in court, arguing that he was responding to how posters were met with panzers and truncheons, and that he is opposed to erecting statues of Öcalan.[18][19]

Opposition leader

Peace process 2013

Demirtaş was the co-chair of BDP during the period when the peace process and negotiations kick-started in Turkey. He was one of the BDP politicians who met Öcalan on Imrali island during the peace negotiations.[20]

2014 Presidential campaign

In 2014 Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ were elected as the co-chairs of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) – a new initiative originating from a three-year-old coalition of the BDP and various different political parties and organization under the auspices of the Peoples' Democratic Congress (HDK) - for the 2014 presidential elections of Turkey, being one of three candidates and hoping to attract left-wing voters.[21] He came third with 9.77% of the vote.

2014 Municipal elections

He stressed that gender equality and a women quota is preeminent in their party program for the elections and announced in October 2013, that for the Metropolis Diyarbakır a female mayor was planned.[22] In the Municipal elections of 2014, Gültan Kisanak was elected the Mayor of Diyarbakir,[23] and Februnye Akyol Co-Mayor of Mardin.[24]

June 2015 general elections

Demirtaş was co-leader along with Figen Yüksekdağ during the June 2015 Turkish general election, the party's first campaign in a general election. The HDP came in fourth place with 13.12% of the vote, breaking for the first time the 10% electoral threshold to enter the parliament,[25][26] sending 80 HDP representative there out of 550 seats.[27] The election results were largely perceived to be a surprise for the opposition, with the HDP having surpassed the election threshold by a healthy 3% of the vote despite many pollsters claiming that it was hovering at the 10% boundary.

HDP co-leader Demirtaş was widely seen as the victor of the election, in the sense that as well as exceeding many vote share projections, his party won the same amount of MPs (80 seats) as the Nationalist Movement Party. The international press characterized Demirtaş as the 'Kurdish Obama' and supporters of the HDP took to the street to celebrate their success on the evening of polling day.[28][29][30] Celebrating the victory, Dermirtaş stated: "From now on, the HDP is Turkey's party. HDP is Turkey, Turkey is HDP."[31]

Other commentators noted the rising difficulties ahead, Demirtaş risking to be undercut by Occalan's political influence, the mechanical rise of anti-Kurdish sentiment among Turkey nationalist forces,[25] and the need to not alienate tactical voters.[32]

Peace talks collapse

.jpg.webp)

In July 2015, the peace process initiated by AKP and PKK leadership and facilitated by HDP collapsed. Demirtaş attributes this collapse to AKP, responding to the June election's votes loss to following parties, loss of its governing majority, and relative electoral defeat. According to Demirtaş, AKP bleeding votes in polls lead this party to reignite the war against PKK.[33] In July 2015, observing an increase in violence between PKK-affiliated parties and Turkish authorities, Demirtaş opposed violence from both parties and called for a higher political autonomy in South-East Turkey.[6]

March on Cizre

When in early September 2015 the Turkish authorities imposed a curfew on the city of Cizre[34] HDP parliamentarians around Demirtas went on a march on Cizre, but were prevented from entering the city by the Turkish authorities who alleged security concerns.[35] He was allowed in the city only after the curfew was lifted[36] on the 12 September.[37]

November 2015 general election

In August 2015, two months after the June 2015 general elections and one month after the return to military confrontation with PKK, early general election were announced for November 2015. HDP, led by Demirtaş, came third, securing 10,7% of the vote, barely passing the parliament's 10% threshold.

2016 to 2018 Presidential campaign

In May 2016, the Turkish parliament revoked the parliamentary immunity for several HDP politicians including the HDP leadership.[6]

Following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, Demirtaş stated in his statement on 16 July that he was against the coup and that the attempt was an indication that there was still no democracy in Turkey.[38][39] On July 25, Erdogan invite and met with major opposition leaders, except HDP leadership and Dermirtaş.[40]

On November 4, 2016, few months after the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt and in the mist of large scale purges, Demirtaş was arrested along with Figen Yüksekdağ and other HDP MPs, accused of spreading propaganda for militants fighting the Turkish state.[41] Demirtaş stated he is not a "manager, member, spokesperson, or sympathizer" of the armed PKK group.[42]

Demirtaş was officially announced as the candidate of the People's Democratic Party (HDP) on May 4, 2018, for the presidential election, after members of the party had hinted at his candidacy weeks in advance.[43] Party leader Pervin Buldan declared that Demirtaş, the jailed former co-chair of the HDP, would be leading a five-party "Kurdish alliance" into the general election.[44] He received 8.4% of the votes.[45]

Legal prosecution and detention

Initial arrest and motive

Demirtaş was arrested on 4 November 2016. The criminal indictment against Demirtaş alleged that in a public statement on the 6 October, the HDP raised support for protests against claimed approach of the Turkish Government shows towards the Islamic State (IS) attack on Kobane.[46] The HDP was blamed for the Kobanî protests in 2014, which resulted in the death of over 50 people[46] despite it having called for an investigation on the events leading to the deaths in parliament which was turned down by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).[46] President Recep Tayyip Erdogan blamed Demirtaş for provoking protests, and said that all Kurdish people are the citizens of Republic of Turkey, and no one can attempt to build a state for them.[47] Demirtaş's repeatedly stated opposition to both PKK and TSK violences,[48] calling killed Turkish soldiers "the children of this country, our children", and declaring "No one has anything to win from a civil war in Turkey. Just look at Syria and Iraq.”[48] His prosecution also used wiretaps as evidence to show relation with the Democratic Society Congress (DTK), which the prosecution views as a part of the PKK.[46]

Main prosecution and appeals

On 18 January 2017, Turkish prosecutors announced they were seeking a 142-year prison sentence for Demirtaş[49] and according to The New York Times, more than hundred charges have been brought against Demirtaş.[50]

On the 7 September 2018 he was sentenced to 4 years and 8 months for a speech he had made at a Newroz celebration on the 20 March 2013.[51]

2018 and 2020 ECHR's judgements

On 20 November 2018 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled Demirtaş should be released from preliminary detention,[52] and ordered Turkey to pay him 25'000 Euros.[53] On 30 November 2018 a court in Turkey ruled he shall remain detained despite the ECHR ruling to release him. According to the verdict by the Turkish court, the ruling of the ECHR was not definitive and therefore not binding.[54] The sentence he received the 7 September 2018 was upheld on 4 December 2018 by an appeal court.[55] On the 31 December 2018 the lawyers of Demirtaş appealed the sentence at the Constitutional Court.[51]

On December 22, 2020, the ECHR condemns Turkey and called again for the release of Selahattin Demirtaş.[6] The Court deemed the lifting of the parliamentary immunity and the subsequent pre-trial detentions as politically motivated because this step came only after the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) had lost its majority in parliament.[56]

Other prosecutions

On 17 March 2021, the state prosecutor Bekir Şahin demanded for him and 686 other HDP politicians a five-year ban to engage in politics together with a closure of the HDP due to alleged organizational cooperation with the PKK.[57]

A few days later on the 22 March 2021, Demirtas was sentenced to three years and six months imprisonment for having insulted the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan by mentioning he had "fluttered from corridor to corridor" trying to meet the Russian president Vladimir Putin during a summit in Paris.[58] The remarks were made after Demirtas's return from Russia at the Atatürk Airport in Istanbul.[59]

Detention

Since 4 November 2016 he is detained in the prison in the F-Type prison Edirne,[51] a border town near Bulgaria and Greece, far away from Diyarbakır in South-Eastern Turkey, where his family lives at. His wife visits him once a week.[60] ECHR called for releasing Demirtaş and stated that his arrest in 2016 violated his freedom of speech and the right of joining to the elections.[61] According to HDP speaker Saruhan Oluç, he is not allowed to receive visits by parliamentarians of the HDP.[62] Since the COVID-19 pandemic his visitors rights are restricted to non-contact visits.[63] As his wife informed the public on in an interview with Ismail Küçükkaya on FOX TV about it, the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) initiated an investigation on the program due to her remarks.[64] In November 2022, he was flown to Diyarbakir where he was shortly allowed to visit his father in hospital.[65] After the short visit, he was brought back to Edirne.[65] His cellmate was for years the fellow HDP politician Abdullah Zeydan who was released in January 2022.[66] In March the same year, the arrested mayor of Diyarbakir Adnan Selçuk Mizrakli became his new cellmate.[67]

Personal life

Demirtaş is of Zaza origin and he knows Zaza language.[68][69] Demirtaş was asked "Aren't you Zaza?" in a programme. In response to this question, he defined himself as "Kurdish Zaza".

Demirtaş is married to Başak Demirtaş and is the father of two girls, Delal and Dılda.[70] His parents are Tahir and Sadyie Demirtaş[71] and he has six siblings.[1]

Demirtaş has faced threats due to his political activity and on November 22, 2015, he survived an assassination attempt.[72]

Electoral history

Presidential

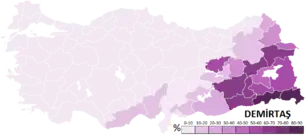

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 3,958,048 | 9.76% | Peoples' Democratic Party | |

| 2018 | 4,205,794 | 8.40% | — |

Parliamentary

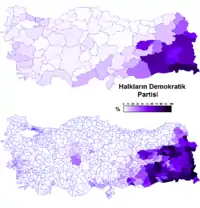

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | Partner | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 June | 6,058,489 | 13.12% | Figen Yüksekdağ | Peoples' Democratic Party |  |

| 2015 November | 5,148,085 | 10.76% |  |

Local

| Election date | Votes | Percentage of votes | Political party | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2,611,127 | 6.29% |

Peace and Democracy Party Peoples' Democratic Party |

Publications

In detention, he wrote a book titled Seher containing short stories.[73] The Turkish edition of Seher has reportedly sold more than 200,000 copies.[74] He has also wrote the book Devran in prison.[75] In 2020 the book Leylan was published and Demirtaş acknowledged he would prefer a career in literature than the one in politics.[75]

Awards

In November 2019, the Progressive Alliance awarded him their Political Courage Award. His wife Başak Demirtaş attended the award ceremony as he was still imprisoned at the time.[76]

2022 Political courage Award by the Institute François Mitterrand.[77] Hişyar Özsoy of the HDP attended the award ceremony of Demirtaş behalf.[77]

References

- Bellaigue, Christopher de (29 October 2015). "The battle for Turkey: can Selahattin Demirtas pull the country back from the brink of civil war?". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Political prisoner says Turkey let down by European rights court". Financial Times. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- "Selahattin Demirtaş kimdir? İşte Demirtaş'ın hayatı". Sözcü. 11 September 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- "Selahattin Demirtaş, Artı Gerçek'e açıkladı: Aktif politikayı bu aşamada bırakıyorum". 31 May 2023. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- Zaman, Amberin (25 April 2018). "Turkey's top Kurdish politician to run for president from behind bars". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Case of Selahattin Demirtas v. Turkey (No. 2) (Application no. 14305/17)". European Court for Human Rights. 22 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Who's who in Politics in Turkey" (PDF). Heinrich Böll Stiftung. pp. 232–235. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Kenner, David (4 November 2016). "Turkey's 'Kurdish Obama' Is Now in Jail". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Jailed 'Kurdish Obama' says he won't run for Turkish elections". France 24. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- WELT (14 August 2009). "Inhaftierter PKK-Chef: Öcalan entwirft "Road Map" für Türken und Kurden". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "No violation of right to life in Demirtaş' case, says ECHR - Türkiye News". Hürriyet Daily News. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Coskun, Vahap (2010). "Turkey's Illiberal Judiciary: Cases and Decisions". Insight Turkey. 12 (4): 43–67. ISSN 1302-177X. JSTOR 26331499.

- "Turkish court bans pro-Kurd party". 11 December 2009. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Gunes, Cengiz (11 January 2013). The Kurdish National Movement in Turkey: From Protest to Resistance. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-136-58798-6.

- "HAKKARİ 2011 GENEL SEÇİM SONUÇLARI". secim.haberler.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Demirtaş: Öcalan'ın heykelini dikeceğiz". www.ntv.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "BDP wants Öcalan statue - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Demirtaş'tan mahkemede 'Öcalan'ın heykelini dikeceğiz' savunması". www.aydinlik.com.tr. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Demirtaş, 'Başkan Apo'nun heykelini dikeceğiz' sözüne açıklık getirdi". www.rudaw.net (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Kurdish Deputies Set Off For Imrali". Bianet. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- "Kurdish problem-focused HDP announces co-chair Demirtaş as presidential candidate". 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "Demirtaş: "The Government De Facto Ended Dialogue Process"". 8 October 2013.

- Zaman, Amberin (12 March 2015). "One woman's journey from prisoner to mayor - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. Al-Monitor. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Güsten, Susanne (14 April 2014). "Mardin elects 25-year old Christian woman as mayor - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. Al-Monitor. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Quilliam, Jonathan Friedman,Neil. "A setback for Kurdish self-rule?". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Trofimov, Yaroslav (19 June 2015). "The State of the Kurds". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Kurdish Party Wins Record Number Of Seats In Turkish Parliament". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Turkey election 2015: Kurdish Obama is the country's bright new star". the Guardian. 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Turkey: Who is 'Kurdish Obama' Selahattin Demirtas and what does he want?". International Business Times UK. 8 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Kurds celebrate gains amid blow to Turkey's AK party". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Selahattin Demirtaş, the Dimming Star of Turkish Politics". Fanack.com. 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Cumhuriyet Gazetesi – Sırrı Süreyya Önder: Emanet oyları mahçup etmeyeceğiz". cumhuriyet.com.tr. 7 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Minute, Turkish (25 August 2021). "HDP couldn't have ended AKP's reconciliation talks with PKK: Demirtaş - Turkish Minute". Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Turkey Kurds: Many dead in Cizre violence as MPs' march blocked". BBC News. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Jacobsen, Lenz; Topçu, Özlem (11 September 2015). "Was geschieht in Cizre?". Die Zeit. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Bernath, Markus (14 September 2015). "Cizre erwacht aus dem Bürgerkrieg". Der Standard (in Austrian German). Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Turkey lifts week-long curfew on Kurdish city of Cizre". BBC. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Demirtaş darbe girişimini kınadı". Ensonhaber (in Turkish). 16 July 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Inside the Long Night of Turkey's Attempted Coup". Time. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Turquie : Erdogan rencontre l'opposition, la purge se poursuit". France 24 (in French). 25 July 2016. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Turkey HDP: Blast after pro-Kurdish leaders Demirtas and Yuksekdag detained". BBC. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- "HDP's Demirtaş: I'm not a manager, member, spokesperson". Birgun. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Lıcalı, Mahmut (29 April 2020). "Demirtaş bugün hâkim karşısında: Ceza çıksa da çıkmasa da aday". www.cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- "HDP nominates imprisoned former leader Demirtaş for presidency". Hürriyet Daily News. 4 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "Seçim Sonuçları: Haziran 2018 Cumhurbaşkanlığı ve Genel Seçim Sonuçları". Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Turkey: Crackdown on Kurdish Opposition". Human Rights Watch. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Erdoğan: '53 kardeşimin kanı Demirtaş'ın eline bulanmıştır'". Internet Haber. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "HDP co-chair Demirtaş calls on PKK to halt violence 'without ifs or buts' - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. 24 August 2015. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (18 January 2017). "Turkish prosecutor demands 142 years imprisonment for Kurdish leader Demirtaş, EU rapporteur outraged". ARA News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Gall, Carlotta (31 July 2018), "Erdogan's Most Charismatic Rival in Turkey Challenges Him, From Jail", The New York Times, ISSN 0362-4331, archived from the original on 8 February 2019, retrieved 10 January 2019

- "Prison Sentence of Selahattin Demirtaş Taken to Constitutional Court". Bianet. 2 January 2019. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "ECHR: Demirtas should be released, his rights were violated". ANF News. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "CASE OF SELAHATTİN DEMİRTAŞ v. TURKEY (No. 2)". European Court of Human Rights. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Eckerd, Patrick (30 November 2018). "Turkish court rules Kurdish opposition will remain leader imprisoned". www.jurist.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Prison Sentences of Demirtaş and Önder Upheld - english". Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Selahattin Demirtaş v. Turkey (no. 2) [GC] - 14305/17 ; Information Note on the Court's case-law 246". European Court for Human Rights. 22 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- "Turkish prosecutor seeks political ban on 687 pro-Kurdish politicians". www.duvarenglish.com (in Turkish). 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- "Turkish court sentences Demirtas to jail for insulting president: lawyer". Reuters. 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- "Turkish court upholds jail sentence against Demirtaş for 'insulting' Erdoğan". Gazete Duvar. 21 February 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Why Kurdish voters could hold the key to Turkey's elections". The Independent. 22 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Daventry, Michael (22 December 2020). "Human rights court orders Turkey to release Kurdish leader Demirtaş". euronews. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Türkische Linke: "Wir machen weiter"". www.woz.ch (in German). 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "Selahattin and Başak Demirtaş denounce RTÜK probe". Bianet. 8 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- "Media authority RTÜK probes Başak Demirtaş's remarks on FOX TV". Bianet. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- "Former HDP co-chair Demirtaş allowed to visit father in Diyarbakır after latter's heart attack". Gazete Duvar (in Turkish). 13 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "Haftentlassung von Abdullah Zeydan angeordnet". ANF News (in German). Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "New picture from jailed politicians Demirtaş, Mızraklı". Bianet.

- "Demirtaş'tan Kürtçe açıklaması: Ben Zazayım, Zazaca biliyorum". Timeturk. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- "Demirtaş'tan Kürtçe bilmiyor haberlerine açıklama". Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Kurdistan24. "Erdogan's presidential rivals, Demirtas, Ince meet in Turkish prison". Kurdistan24. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "First Prison Photo of HDP Co-Chair Demirtaş Released". Bianet. 3 February 2017. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "HDP says co-leader escaped an assassination attempt". 23 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Jailed Kurdish leader becomes literary star behind bars". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Jo Glanville (23 June 2018). "Inside stories: Turkey's grim tradition of publishing behind bars". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Devran: Selahattin Demirtaş and stubborn hope". Ahval. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Jailed Kurdish leader Demirtaş receives international award for political courage". Ahval. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- "Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtaş granted Political Courage Award". Gazete Duvar. 13 January 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

Further reading

- Demirtaş, Selahattin (10 March 2016). "Demirtas: The Kurds and Turkey's Democracy is at Stake". Newsweek.

External links

Quotations related to Selahattin Demirtaş at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Selahattin Demirtaş at Wikiquote Media related to Selahattin Demirtaş at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Selahattin Demirtaş at Wikimedia Commons