Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811 – March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American advocate for the abolition of slavery. He chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1861 to 1871, until he lost the position following a dispute with President Ulysses S. Grant over the attempted annexation of Santo Domingo. After breaking with Grant, he joined the Liberal Republican Party. He spent his final two years in the Senate alienated from his party. Sumner had a controversial and divisive legacy for many years after his death, but in recent decades, his historical reputation has improved in recognition of his early support for racial equality.

Charles Sumner | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1865 | |

| Dean of the United States Senate | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 11, 1874 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Wade |

| Succeeded by | Zachariah Chandler |

| Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 4, 1871 | |

| Preceded by | James M. Mason |

| Succeeded by | Simon Cameron |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

| In office April 25, 1851 – March 11, 1874 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Rantoul Jr. |

| Succeeded by | William B. Washburn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 6, 1811 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | March 11, 1874 (aged 63) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery |

| Political party | Whig (1840–1848) Free Soil (1848–1854) Republican (1854–70) Liberal Republican (1870–1872) |

| Other political affiliations | Radical Republicans (1854–70) |

| Spouse |

Alice Hooper

(m. 1866; div. 1873) |

| Relatives | Sumner family |

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB) |

| Signature | |

Sumner began his political activism as a member of various anti-slavery groups, leading to his election to the U.S. Senate in 1851 as a member of the Free Soil Party; he soon became a founding member of the Republican Party. In the Senate, he devoted his efforts to opposing the "Slave Power,"[1] which culminated in a vicious beating by Representative Preston Brooks on the Senate floor in 1856; Sumner's severe injuries and extended absence from the Senate made him a symbol of the anti-slavery cause. Though he did not return to the Senate until 1859, Massachusetts reelected him in 1857, leaving his empty desk as a reminder of the incident, which polarized the nation as the Civil War approached.

During the war, Sumner led the Radical Republican faction critical of President Abraham Lincoln for being too moderate toward the South. As chair of the Foreign Relations committee, Sumner worked to ensure that the United Kingdom and France did not intervene on behalf of the Confederate States. After the Union won the war and Lincoln was assassinated, Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens led congressional efforts to grant equal civil and voting rights to freedmen and to block ex-Confederates from power so they would not reverse the gains derived from the Union's victory in the war. President Andrew Johnson's persistent opposition to these efforts played a role in his impeachment in 1868.

During the Grant administration, Sumner fell out of favor with his party. He supported the annexation of Alaska, but opposed Grant's proposal to annex Santo Domingo. After leading senators to defeat the Santo Domingo Treaty in 1870, Sumner denounced him in such terms that reconciliation was impossible, and Senate Republicans stripped him of his power. Sumner opposed Grant's 1872 reelection and supported Liberal Republican Horace Greeley. He died in office less than two years later.

Early life, education, and law career

Charles Sumner was born on Irving Street in Boston on January 6, 1811. His father, Charles Pinckney Sumner, was a Harvard-educated lawyer, abolitionist, and early proponent of racial integration of schools, who shocked 19th-century Boston by opposing anti-miscegenation laws.[2] His mother, Relief Jacob, worked as a seamstress before marrying Charles.[3]

Both of Sumner's parents were born in poverty and were described as exceedingly formal and undemonstrative.[4] His father served as Clerk of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1806 to 1807 and from 1810 to 1811, and had a moderately successful legal practice. Throughout Sumner's childhood, his family teetered on the edge of the middle class.[5] Charles P. Sumner hated slavery and further told his son that freeing the slaves would "do us no good" unless society treated them equally.[6] He was a close associate of Unitarian leader William Ellery Channing. Expanding on Channing's argument that human beings had infinite potential to improve themselves, Sumner concluded that environment had "an important, if not controlling influence" in shaping people.[7] Thus, if society gave precedence to "knowledge, virtue and religion", then "the most forlorn shall grow into forms of unimagined strength and beauty."[8] Moral law, he believed, was as important for governments as it was for individuals, and legal institutions that inhibited personal progress—like slavery or segregation—were evil.[8]

The family's fortunes improved in 1825, when Charles P. Sumner became Sheriff of Suffolk County; he held the position until his death in 1838.[9] The family attended Trinity Church, but after 1825, they occupied a pew in King's Chapel.[10] Sumner's father was also able to provide higher education for his children; the young Charles attended Boston Latin School, where he befriended Robert Charles Winthrop, James Freeman Clarke, Samuel Francis Smith, and Wendell Phillips.[2] In 1830, he graduated from Harvard College, where he lived in Hollis Hall and was a member of the Porcellian Club. He then attended Harvard Law School, where he became a protégé of Joseph Story and an enthusiastic student of jurisprudence.[11]

After graduating in 1834, Sumner was admitted to the bar and entered private practice in Boston in partnership with George Stillman Hillard. A visit to Washington decided him against a political career, and he returned to Boston resolved to practice law.[11] He contributed to the quarterly American Jurist and edited Story's court decisions as well as some law texts. From 1836 to 1837, Sumner lectured at Harvard Law School.

Travels in Europe

In 1837, Sumner visited Europe with financial support from benefactors, including Story and Congressman Richard Fletcher. He landed at Le Havre and found the cathedral at Rouen striking: "The great lion of the north of France … transcending all that my imagination had pictured."[12] He reached Paris in December, studied French, and visited the Louvre.[13] He mastered French within six months and attended lectures at the Sorbonne on subjects ranging from geology to Greek history to criminal law.[14]

In his journal for January 20, 1838, Sumner noted that one lecturer "had quite a large audience among whom I noticed two or three blacks, or rather mulattos—two-thirds black perhaps—dressed quite à la mode and having the easy, jaunty air of young men of fashion…" who were "well received" by the other students after the lecture. He continued:[15]

They were standing in the midst of a knot of young men and their color seemed to be no objection to them. I was glad to see this, though with American impressions, it seemed very strange. It must be then that the distance between free blacks and whites among us is derived from education, and does not exist in the nature of things.

Sumner decided that Americans' predisposition to see blacks as inferior was a learned viewpoint, and he determined to become an abolitionist upon returning to America.[16]

Over the next three years, Sumner became fluent in Spanish, German, and Italian,[17] and met with many leading European statesmen.[18] In 1838, he visited Britain, where Lord Brougham declared that he "had never met with any man of Sumner's age of such extensive legal knowledge and natural legal intellect".[19] Though he often praised British society as more refined than American, Sumner published a fierce defense of the American position in the dispute over the Maine-Canada boundary, circulated by Minister to France Lewis Cass.[19]

In 1840, at age 29, Sumner returned to Boston to practice law but devoted more time to lecturing at Harvard Law, editing court reports, and contributing to law journals, especially on historical and biographical themes.[11][20]

Sumner developed friendships with several prominent Bostonians, particularly Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose house he visited regularly in the 1840s.[21] Longfellow's daughters found his stateliness amusing; he would ceremoniously open doors for the children while saying "In presequas" ("after you") in a sonorous tone.[21]

Early political activism

Sumner embarked on a public political career in 1845, when he emerged as one of the most prominent critics of slavery in the city of Boston and the state of Massachusetts, a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment.

In July, Sumner delivered the Boston Independence Day oration, on the subject The True Grandeur of Nations. His speech was critical of the move toward war with Mexico and an impassioned appeal for freedom and peace.[11] Sumner considered the conflict a war of aggression but was primarily concerned that captured territories would expand slavery westward. He soon became a sought-after orator for formal occasions throughout Boston. His lofty themes and stately eloquence made a profound impression. His platform presence was imposing. He stood 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) tall, with a massive frame. His voice was clear and powerful. His gestures were unconventional and individual, but vigorous and impressive. His literary style was florid, with much detail, allusion, and quotation, often from the Bible as well as the Greeks and Romans.[11] Longfellow wrote that he delivered speeches "like a cannoneer ramming down cartridges", while Sumner himself said that "you might as well look for a joke in the Book of Revelation."[22]

Following the annexation of Texas as a slave state in December, Sumner took an active role in the anti-slavery movement. In 1847, he denounced the declaration of war against Mexico with such vigor that he was recognized as a leader of the "Conscience" faction of the Massachusetts Whig Party. He declined the Whig nomination for the United States House of Representatives in 1848,[11] instead helping organize the Free Soil Party and becoming chairman of the state party's executive committee, a position he used to advocate for abolition and build a coalition that included anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats.[23]

Sumner also took an active role in other social causes. He worked with Horace Mann to improve Massachusetts's system of public education, advocated prison reform, and represented the plaintiffs in Roberts v. City of Boston, which challenged the legality of racial segregation in public schools. Arguing before the Massachusetts Supreme Court, Sumner noted that schools for blacks were physically inferior and that segregation bred harmful psychological and sociological effects—arguments made in Brown v. Board of Education over a century later.[24] Sumner lost the case, but the Massachusetts General Court abolished school segregation in 1855.

United States Senate (1851–1874)

In 1851, a coalition of Democratic and Free Soil legislators gained control of the Massachusetts General Court. In exchange for Free Soil support for Democratic governor Robert Boutwell, the Free Soil Party named Sumner its choice for U.S. Senate. Despite the private agreement, conservative Democrats opposed his candidacy and called for a less radical candidate. The impasse was broken after three months and Sumner was elected on a parliamentary technicality by a one-vote majority on April 24, 1851, in part thanks to the support of Senate President Henry Wilson.[25] His election marked a sharp break in Massachusetts politics, as his abolitionist politics contrasted sharply those of his best-known predecessor in the seat, Daniel Webster, one of the foremost supporters of the Compromise of 1850 and its Fugitive Slave Act.[26]

For the first few sessions, Sumner did not promote any of his controversial causes. On August 26, 1852, he delivered his maiden speech, despite strenuous efforts to dissuade him. This oratorical effort incorporated a popular abolitionist motto, "Freedom National; Slavery Sectional," as its title. In it, Sumner attacked the Fugitive Slave Act.[27] Though both major party platforms affirmed every provision of the Compromise of 1850 as final, including the Fugitive Slave Act, Sumner called for its repeal. For more than three hours, he denounced it as a violation of the Constitution, an affront to the public conscience, and an offence against divine law.[28] After his speech, a senator from Alabama urged that there be no reply: "The ravings of a maniac may sometimes be dangerous, but the barking of a puppy never did any harm." Sumner's outspoken opposition to slavery made him few friends in the Senate.[29]

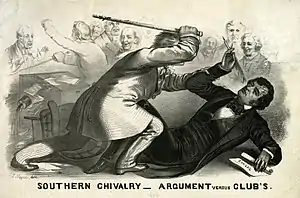

The "Crime against Kansas" and beating by Preston Brooks

On May 19 and 20, 1856, during the civil unrest known as "Bleeding Kansas," Sumner denounced the Kansas–Nebraska Act in his "Crime against Kansas" speech.[30] The long speech argued for Kansas's immediate admission as a free state and denounced "Slave Power"—the political power of the slave owners. Their motivation, he alleged, was to spread slavery even to free territories:[31]

Not in any common lust for power did this uncommon tragedy have its origin. It is the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State, hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the National Government.[32]

Sumner verbally attacked authors of the Act, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina:

The senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, slavery. For her his tongue is always profuse in words. Let her be impeached in character, or any proposition made to shut her out from the extension of her wantonness, and no extravagance of manner or hardihood of assertion is then too great for this senator.

Two days later, on the afternoon of May 22, Representative Preston Brooks, Butler's first cousin once removed,[33][34] confronted Sumner in the Senate chamber and beat him severely on the head, using a thick gutta-percha cane with a gold head. Sumner was knocked down and trapped under the heavy desk, which was bolted to the floor. Blinded by his own blood, he staggered up the aisle and collapsed into unconsciousness. Brooks continued to beat the motionless Sumner until his cane broke, at which point he continued to strike Sumner with the remaining piece.[35] Several other senators attempted to help Sumner, but were blocked by Laurence Keitt, who brandished a pistol and shouted, "Let them be!"[36]

The episode became a symbol of polarization in the antebellum period; Sumner became a martyr in the North and Brooks a hero in the South. Thousands attended rallies in support of Sumner throughout the North. Louisa May Alcott described a rally in Boston on November 3 in a letter to Anna Alcott: "Eight hundred gentlemen on horseback escorted him and formed a line up Beacon St. through which he rode smiling and bowing, he looked pale but otherwise as usual. The only time Sumner rose along the route was when he passed the Orphan Asylum and saw all the little blue aproned girls waving their hands to him. I thought it was very sweet in him to do that honor to the fatherless and motherless children. A little child was carried out to give him a great bouquet, which he took and kissed the baby bearer. The streets were lined with wreaths, flags, and loving people to welcome the good man back....and tho I was only a 'love lorn' governess I waved my cotton handkerchief like a meek banner to my hero with honorable wounds on his head and love of little children in his heart. Hurra!! I could not hear the speeches at the State House so I tore down Hancock St. and got a place opposite his house. I saw him go in, and soon after the cheers of the horsemen and crowd brought him smiling to the window, he only bowed, but when the leader of the cavelcade cried out 'Three cheers for the mother of Charles Sumner!' he stepped back and soon appeared leading an old lady who nodded, waved her hand, put down the curtain, and then with a few dozen more cheers the crowd dispersed. I was so excited I pitched about like a mad woman, shouted, waved, hung onto fences, rushed thro crowds, and swarmed about in a state of rapterous insanity till it was all over and then I went home hoarse and worn out."

More than a million copies of Sumner's "Crime against Kansas" speech were distributed. Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked, "I do not see how a barbarous community and a civilised community can constitute one state. I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom."[37] Conversely, Brooks was praised by Southern newspapers. The Richmond Enquirer editorialized that Sumner should be caned "every morning" and Southerners sent Brooks hundreds of new canes in endorsement of his assault. Southern lawmakers made rings out of the cane's remains, which they wore on neck chains to show solidarity with Brooks.[38]

Historian William Gienapp has concluded that Brooks's "assault was of critical importance in transforming the struggling Republican party into a major political force."[39] Theological and legal scholar William R. Long characterized the speech as "a most rebarbative and vituperative speech on the Senate floor", which "flows with Latin quotations and references to English and Roman history." In his eyes, the speech was "a gauntlet thrown down, a challenge to the 'Slave Power' to admit once and for all that it were encircling the free states with their tentacular grip and gradually siphoning off the breath of democracy-loving citizens."[31]

In addition to head trauma, Sumner suffered "psychic wounds," now understood to be post-traumatic stress disorder.[40][41] When he spent months convalescing, his political enemies ridiculed him and accused him of cowardice for not resuming his duties. The Massachusetts General Court reelected him in November 1856, believing that his vacant chair in the Senate chamber served as a powerful symbol of free speech and resistance to slavery.[42]

When Sumner returned to the Senate in 1857, he was unable to last a day. His doctors advised a sea voyage and "a complete separation from the cares and responsibilities that must beset him at home." He sailed for Europe and immediately found relief.[41] During two months in Paris in the spring of 1857, he renewed friendships, especially with Thomas Gold Appleton, dined out frequently, and attended the opera. His contacts there included Alexis de Tocqueville, poet Alphonse de Lamartine, former French Prime Minister François Guizot, Ivan Turgenev, and Harriet Beecher Stowe.[41] Sumner toured several countries, including Prussia and Scotland, before returning to Washington, where he spent only a few days in the Senate in December. Both then and during several later attempts to return to work, he found himself exhausted just listening to Senate business. He sailed once more for Europe on May 22, 1858, the second anniversary of Brooks's attack.[41]

In Paris, prominent physician Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard diagnosed Sumner's condition as spinal cord damage that he could treat by burning the skin along the spinal cord. Sumner chose to refuse anaesthesia, which was thought to reduce the effectiveness of the procedure. Observers both at the time and since doubt Brown-Séquard's efforts were of value.[41] After spending weeks recovering from these treatments, Sumner resumed his touring, this time as far east as Dresden and Prague and south to Italy twice. In France he visited Brittany and Normandy, as well as Montpellier. He wrote his brother: "If anyone cares to know how I am doing, you can say better and better."[43]

In 1859, Sumner returned to the Senate permanently. Though fellow Republicans advised a less strident tone, he answered: "When crime and criminals are thrust before us, they are to be met by all the energies that God has given us by argument, scorn, sarcasm and denunciation." He delivered his first return speech, "The Barbarism of Slavery," on June 4, 1860. He attacked attempts to depict slavery as a benevolent institution, said it stifled economic development in the South, and that it left slaveholders reliant on "the bludgeon, the revolver, and the bowie-knife". He addressed an anticipated objection on the part of one of his colleagues: "Say, sir, in your madness, that you own the sun, the stars, the moon; but do not say that you own a man, endowed with a soul that shall live immortal, when sun and moon and stars have passed away." Even allies found his language too strong, one calling it "harsh, vindictive, and slightly brutal".[44] He spent the summer rallying the anti-slavery forces for the election of 1860 and opposing talk of compromise.[44]

Civil War

After the Civil War began, Sumner was among the Radical Republicans who advocated immediate abolition of slavery and the destruction of the Southern planter class.[45] Although like-minded on slavery, the Radicals were loosely organized and disagreed on issues such as the tariff and currency.[46] Other Radicals in the Senate included Zachariah Chandler and Benjamin Wade.[45] After the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Sumner, Chandler and Wade repeatedly visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House to discuss slavery and the rebellion.[45] Gilbert Osofsky argues that Sumner saw the war as a "death struggle" between "two mutually contradictory civilizations," and his solution was "to 'civilize' and 'Americanize' the South" by conquest, then forcibly mold it into a society defined in Northern terms, as an idealized version of New England.[47]

Throughout the war, Sumner had been the special champion of black Americans, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting blacks in the Union Army, and of the establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau.[28]

Emancipation

The Radicals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves and persistently lobbied for it as wartime policy, but Lincoln was resistant, since the slave states Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri would be encouraged to join the Confederacy.[45] Lincoln instead adopted a plan for gradual emancipation and compensation to slavers, but consulted Sumner frequently.[48][49] Despite their disagreements, Lincoln called Sumner "my idea of a bishop" and an embodiment the American people's conscience.[48]

In May 1861, Sumner counseled Lincoln to make emancipation the war's primary objective.[49] He believed that military necessity would eventually force Lincoln's hand and that emancipation would give the Union higher moral standing, which would keep Britain from entering the Civil War on the Confederacy's side.[49][45] In October 1861, at the Massachusetts Republican Convention in Worcester, Sumner openly expressed his belief that slavery was the war's sole cause and that the Union government's primary objective was to end it. Sumner argued that Lincoln could command the Union Army to emancipate slaves under color of martial law.[49] In the conservative press, Sumner's speech was denounced as incendiary.[49] Conservative Massachusetts newspapers editorialized that he was mentally ill and a "candidate for the insane asylum,"[49] but the Radicals fully endorsed Sumner's speech, and he continued to advance his argument publicly.[49] As an intermediate measure, the Radicals passed two Confiscation Acts in 1861 and 1862 that allowed the military to emancipate confiscated slaves whom the Confederate military had impressed into service.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, abolishing slavery in all Confederate territory.[45] The Thirteenth Amendment subsequently abolished the practice of chattel slavery.

Foreign relations

After the withdrawal of Southern senators, Sumner became chair of the Committee on Foreign Relations in March 1861.[28] As chair, he renewed his efforts for diplomatic recognition of Haiti. Haiti had sought recognition since winning independence in 1804 but faced opposition from Southern senators. In their absence, the United States recognized Haiti in 1862.[50]

On November 8, 1861, the Union naval ship USS San Jacinto intercepted the British steamer RMS Trent. Two Confederate diplomats aboard were placed into port custody.[51] In response to the capture, the British government dispatched 8,000 British troops to the Canadian border and sought to strengthen the British fleet.[51] Secretary of State William Seward believed the diplomats were contraband of war, but Sumner argued the men did not qualify as such because they were unarmed. He favored their release with an apology by the U.S. government. In the Senate, Sumner suppressed open debate in order to save Lincoln's administration from embarrassment. On December 25, 1861, at Lincoln's invitation, Sumner addressed the cabinet. He read letters from prominent British political figures, including Richard Cobden, John Bright, William Ewart Gladstone, and the Duke of Argyll as evidence that political sentiment in Britain supported the envoys' return to the British.[52] Lincoln quietly but reluctantly ordered the captives' release to British custody and apologized. After the Trent affair, Sumner's reputation improved among conservative Northerners.[51]

Reconstruction and Civil rights

As one of the Radical Republican leaders in the post-war Senate, Sumner fought to provide equal civil and voting rights for freedmen on the grounds that "consent of the governed" was a basic principle of American republicanism.

Sumner's radical legal theory of Reconstruction proposed that nothing beyond the confines of the Constitution, read in light of the Declaration of Independence, restricted Congress's treatment of the rebelling states. Though not as radical as Thaddeus Stevens, who considered the Confederate states "conquered provinces," Sumner argued that by declaring secession, the state governments had committed felo de se (state suicide) and could be regulated as territories that should be prepared for statehood, under conditions set by the national government.

Sumner emerged as an idealist and a champion for civil rights through this turbulent and controversial period.[53] He joined fellow Republicans in overriding President Andrew Johnson's vetoes, though his most radical ideas were not implemented. Sumner favored partial male suffrage with a literacy requirement for all southerners in order to vote.[54] Instead, Congress imposed a loyalty requirement the following year; Sumner was strongly supportive.[54]

Sumner was a friend of Samuel Gridley Howe and a guiding force for the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, started in 1863. He was one of the most prominent advocates for suffrage for blacks, along with free homesteads and free public schools. His uncompromising attitude did not endear him to moderates and his arrogance and inflexibility often inhibited his effectiveness as a legislator. He was largely excluded from work on the Thirteenth Amendment, in part because he did not get along with Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull, who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee and did much of the work on it. Sumner introduced an alternative amendment that combined the Thirteenth Amendment with elements of the Fourteenth Amendment. It would have abolished slavery and declared that "all people are equal before the law." During Reconstruction, he often attacked civil rights legislation as inadequate and fought for legislation to give land to freed slaves and to mandate education for all, regardless of race, in the South. He viewed segregation and slavery as two sides of the same coin.[55] He introduced a civil rights bill in 1872 to mandate equal accommodation in all public places and required suits brought under the bill to be argued in the federal courts.[56] The bill failed, but Sumner revived it in the next Congress, and on his deathbed begged visitors to see that it did not fail.[57]

Sumner repeatedly tried to remove the word "white" from naturalization laws. He introduced bills to that effect in 1868 and 1869, but neither came to a vote. On July 2, 1870, Sumner moved to amend a pending bill in a way that would strike the word "white" wherever in all Congressional acts pertaining to naturalization of immigrants. On July 4, 1870, he said: "Senators undertake to disturb us … by reminding us of the possibility of large numbers swarming from China; but the answer to all this is very obvious and very simple. If the Chinese come here, they will come for citizenship or merely for labor. If they come for citizenship, then in this desire do they give a pledge of loyalty to our institutions; and where is the peril in such vows? They are peaceful and industrious; how can their citizenship be the occasion of solicitude?" He accused legislators promoting anti-Chinese legislation of betraying the principles of the Declaration of Independence: "Worse than any heathen or pagan abroad are those in our midst who are false to our institutions." Sumner's bill failed, and from 1870 to 1943, and in some cases as late as 1952, Chinese and other Asians were ineligible for naturalized U.S. citizenship.[58] Sumner remained a champion of civil rights for blacks. He co-authored the Civil Rights Act of 1875 with John Mercer Langston[59] and introduced the bill in the Senate on May 13, 1870. The bill passed a year after his death, in February 1875, and President Grant signed it into law on March 1. It was the last civil rights legislation for 82 years until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1883 when it decided a group of cases known as the Civil Rights Cases.[60]

When Johnson was impeached, Sumner voted for conviction at his trial. He was only sorry that he had to vote on each article of impeachment, for as he said, he would have rather voted, "Guilty of all, and infinitely more."[61]

Alaska annexation

Throughout March 1867, Secretary William H. Seward and Russian representative Edouard de Stoeckl met in Washington, D.C., and negotiated a treaty for the annexation and sale of the Russian American territory of Alaska to the United States for $7,200,000.[62] President Johnson submitted the treaty to Congress for ratification with Sumner's approval, and on April 9, his foreign relations committee approved and sent the treaty to the Senate. In a three-hour speech, Sumner spoke in favor of the treaty on the Senate floor, describing in detail Alaska's imperial history, natural resources, population, and climate. Sumner wanted to block British expansion from Canada, arguing that Alaska was geographically and financially strategic, especially for the Pacific Coast States. He said Alaska would increase America's borders, spread republican institutions, and represent an act of friendship with Russia. The treaty won its needed two-thirds majority by one vote.[62]

The 1867 treaty neither formally recognized, categorised, nor compensated any native Alaskan Eskimos or Indians, referring to them only as "uncivilized tribes" under the control of Congress.[63] By federal law, Native Alaskan tribes, including the Inuit, the Aleut, and the Athabascan, were entitled only to land that they inhabited.[63] According to treaty, native Alaskan tribes were excluded from U.S. citizenship, but citizenship was available to Russian residents. Creoles, persons of Russian and Indian descent, were considered Russian.[64] Sumner said the new territory should be called by its Aleutian name, Alaska, meaning "great land."[65] He advocated for free public education and equal protection laws for U.S. citizens in Alaska.[65]

Personal achievements in 1867 included his election as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[66]

CSS Alabama claims

Sumner was well regarded in the United Kingdom, but after the war he sacrificed his reputation in the U.K. with his stand on U.S. claims for British breaches of neutrality. The U.S. had claims against Britain for the damage inflicted by Confederate raiding ships fitted out in British ports. Sumner held that since Britain had accorded the rights of belligerents to the Confederacy, it was responsible for extending the duration of the war and consequent losses. In 1869, he asserted that Britain should pay damages for not merely the raiders, but also "that other damage, immense and infinite, caused by the prolongation of the war", specifically the British blockade runners, which were estimated to have given the Confederacy 60% of its weapons, 1/3 of the lead for its bullets, 3/4 ingredients for its powder, and most of the cloth for its uniforms;[67] some historians believe that this may have lengthened the war by two years and cost 400,000 more lives of soldiers and civilians on both sides.[68] He demanded $2,000,000,000 for these "national claims" in addition to $125,000,000 for damages from the raiders. Sumner did not expect that Britain ever would or could pay this sum, but he suggested that Britain turn over Canada as payment.[69] This proposition offended many Britons, but was taken seriously by many Americans, including the Secretary of State, whose support for it nearly derailed the settlement with Great Britain in the months before the arbitration conference met at Geneva. At the Geneva arbitration conference in 1871, which settled U.S. claims against Britain, the panel of arbitrators refused to consider those "national claims."

Sumner had some influence over J. Lothrop Motley, the U.S. ambassador to Britain, causing him to disregard the instructions of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish on the matter. This offended President Grant, but while it would be given as the official reason for Motley's removal, was not really so pressing: the dismissal took place a year after Motley's alleged misbehavior, and the real reason was an act of spite by Grant against Sumner.[69]

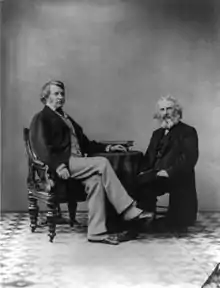

Dominican Republic annexation treaty

In 1869, President Grant, in an expansionist plan, looked into the annexation of a Caribbean island country, the Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo. Grant believed that the island's mineral resources would be valuable to the United States, and that African Americans repressed in the South would have a safe haven to which to migrate. A labor shortage in the South would force Southerners to be tolerant toward African Americans.[70][71] In July and November 1869, under Grant's authority and with the State Department's permission on the second trip, Orville Babcock, Grant's private secretary, secretly negotiated a treaty with President Buenaventura Báez of the Dominican Republic. The initial treaty had not been authorized by the State Department, but the island nation was on the verge of a civil war between Báez and ex-President Marcos A. Cabral.[72] Grant sent in the U.S. Navy to keep the Dominican Republic free from invasion and civil war while the treaty negotiations took place. This military action was controversial since the naval protection was unauthorized by Congress.[73] The official treaty, drafted by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish in October 1869, annexed the Dominican Republic to the United States, gave eventual statehood, the lease of Samaná Bay for $150,000 yearly, and a $1,500,000 payment of the Dominican national debt.[74] In January 1870, in order to gain support for the treaty, Grant visited Sumner's Washington home and mistakenly believed that Sumner had consented to the treaty. Sumner said that he had only promised to give the treaty friendly consideration. This meeting led to bitter contention between Sumner and Grant.[75] The treaty was formally submitted to the United States Senate on January 10, 1870.[76]

The Dominican Republic annexation treaty caused bitter contention between President Grant and Senator Sumner.

Sumner, opposed to American imperialism in the Caribbean and fearful that annexation would lead to the conquest of the neighboring black republic of Haiti, became convinced that corruption lay behind the treaty, and that men close to Grant shared in the corruption. As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he initially withheld his opinion on the treaty on January 18, 1870.[77] Sumner had been leaked information from Assistant Secretary of State Bancroft Davis that U.S. Naval ships were being used to protect Báez. Sumner's committee voted against annexation and, at Sumner's suggestion and possibly to save the party from an ugly fight or Grant from embarrassment, the Senate debated the treaty behind closed doors in executive session. Grant persisted and sent messages to Congress in favor of annexation on March 14 and May 31, 1870.[77] In closed session, Sumner spoke out against the treaty, warning that there would be difficulty with the foreign nationals, noting the chronic rebellion on the island and the risk that the independence of Haiti, recognized by the U.S. in 1862, would be lost. He said that Grant's use of the U.S. Navy as a protectorate was a violation of international law and unconstitutional.[78] Finally, on June 30, 1870, the treaty was voted on by the Senate and failed to gain the 2/3 majority required for passage.[77]

The next day, Grant, feeling betrayed by Sumner, retaliated by ordering the dismissal of Sumner's close friend John Lothrop Motley, Ambassador to Britain.[77] By autumn, Sumner's personal hostility to Grant was public knowledge, and he blamed the Secretary of State for failing to resign rather than let Grant have his way. The two men, friends until then, became bitter enemies. In December 1870, still fearful that Grant meant to acquire Santo Domingo somehow, Sumner gave a fiercely critical speech accusing him of usurpation and Babcock of unethical conduct. Already Grant, supported by Fish, had initiated a campaign to depose Sumner from the chairmanship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Although Sumner said he was an "Administration man," in addition to having stopped Grant's Dominican Republic treaty attempt, Sumner had defeated Grant's full repeal of the Tenure of Office Act, blocked Grant's nomination of Alexander Stewart as Secretary of Treasury, and been a constant harassing force pushing Reconstruction policies faster than Grant had been willing to go. Grant also resented Sumner's superior manner. Told that Sumner did not believe in the Bible, Grant supposedly said he was not surprised: "He didn't write it."[79] As the rift between Grant and Sumner increased, Sumner's health began to decline. When the 42nd U.S. Congress convened on March 4, 1871, senators affiliated with Grant, known as "New Radicals" voted to oust Sumner from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairmanship.[80][81]

Liberal Republican revolt

Sumner now turned against Grant. Like many other reformers, he decried the corruption in Grant's administration. Sumner believed that the civil rights program he championed could not be carried through by a corrupt government. In 1872, he joined the Liberal Republican Party, which had been started by reformist Republicans such as Horace Greeley. The Liberal Republicans supported black suffrage, the three Reconstruction amendments, and the basic civil rights already protected by law, but also called for amnesty for ex-Confederates and decried the Republican governments in the South elected with the help of black votes, belittled the terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan, and argued that the time had come to restore "home rule" in the South, which in practical terms meant white Democratic rule. For Sumner's civil rights bill they gave no support at all, but Sumner joined them because he convinced himself that the time had come for reconciliation, and that Democrats were sincere in declaring that they would abide by the Reconstruction settlement.[82]

Conciliation to South

Sumner never saw his support for civil rights as hostile to the South. On the contrary, he had always contended that a guarantee of equality was the one condition essential for true reconciliation. Unlike some other Radical Republicans, he had strongly opposed any hanging or imprisonment of Confederate leaders. In December 1872, he introduced a Senate resolution providing that Civil War battle names should not appear as "battle honors" on the regimental flags of the U.S. Army. The proposal was not new: Sumner had offered a similar resolution on May 8, 1862, and in 1865 he had proposed that no painting hanging in the Capitol portray scenes from the Civil War, because, as he saw it, keeping alive the memories of a war between a people was barbarous. His proposal did not affect the vast majority of battle-flags, as nearly all the regiments that fought had been state regiments, and these were not covered. But Sumner's idea was that any U.S. regiment that would in the future enlist southerners as well as northerners should not carry on its ensigns any insult to those who joined it. His resolution had no chance of passing, but its presentation offended Union army veterans. The Massachusetts legislature censured Sumner for giving "an insult to the loyal soldiery of the nation" and as "meeting the unqualified condemnation of the people of the Commonwealth." Poet John Greenleaf Whittier led an effort to rescind that censure the following year. He succeeded early in 1874 with the help of abolitionist Joshua Bowen Smith, who was serving in the legislature that year.[83] Sumner was able to hear the rescinding resolution presented to the Senate on the last day he was there. He died the next afternoon.[84]

Virginius Affair

On October 30, 1873, the Virginius, a munitions and troop transportation ship supporting the Cuban Rebellion and flying the U.S. flag, was captured by Spanish authorities.[85] After a hasty trial in Santiago, Cuba, Spain executed 53 crew members, including American and British citizens.[86] Sumner sympathized with the Cuban rebels and those executed by Spain, but refused to support U.S. military intervention or the annexation of Cuba.[87] On November 17, 1873, Sumner stated his views in an interview on the Virginius Affair at a local library in Boston.[87] He believed that although the ship was flying a U.S. flag, its mission was illegal.[88] Sumner, who opposed the Cuban insurgent neutrality of the Grant Administration, believed that the United States needed to support the First Spanish Republic.[88] On November 28, 1873,

Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, who coolly handled the incident amid national outcries for war, negotiated a peaceful settlement with Spanish President Emilio Castelar, and prevented war with Spain.[89]

Death

Long ailing, Charles Sumner died of a heart attack at his home in Washington, D.C., on March 11, 1874, aged 63, after serving nearly 23 years in the Senate. He lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda,[90] the second senator (Henry Clay being the first, in 1852) and fourth person so honored. At his March 16 burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the pallbearers included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and John Greenleaf Whittier.[91]

In the aftermath, Mississippi Senator Lucius Lamar's eulogy for Sumner was controversial enough considering his Southern heritage that the incident resulted in Lamar's inclusion in John F. Kennedy's book Profiles in Courage.[92]

Historical interpretations

Contemporaries and historians have explored Sumner's personality and public career at length. Sumner's reputation among historians in the first half of the 20th century was largely negative—he was particularly blamed by both the Dunning School and anti-Dunning revisionists for the excesses of Radical Reconstruction, which, in the prevailing scholarship, included letting blacks vote and hold office.[93][94] But as perceptions of Reconstruction changed in recent years, so too have perceptions of Sumner.[53] Modern scholars have emphasized his role as a foremost champion of black rights before, during, and after the Civil War; one historian says he was "perhaps the least racist man in America in his day."[95]

Sumner's personality has also divided contemporaries and historians. Sumner's friend Senator Carl Schurz praised Sumner's integrity, his "moral courage," the "sincerity of his convictions," and the "disinterestedness of his motives." But none of his friends at the time doubted his courage, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, who knew Sumner well, remembered that southerners in the 1850s in Washington wondered, every time Sumner left his house in the morning, whether he would return alive.[96] Just before he died, Sumner turned to his friend Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar. "Judge," he said, "tell Emerson how much I love and revere him." "He said of you once," Hoar replied, "that he never knew so white a soul."[97]

Moorfield Storey, Sumner's private secretary for two years and subsequent biographer, wrote of him:

Charles Sumner was a great man in his absolute fidelity to principle, his clear perception of what his country needed, his unflinching courage, his perfect sincerity, his persistent devotion to duty, his indifference to selfish considerations, his high scorn of anything petty or mean. He was essentially simple to the end, brave, kind, and pure…. Originally modest and not self-confident, the result of his long contest was to make him egotistical and dogmatic. There are few successful men who escape these penalties of success, the common accompaniment of increasing years….Sumner's naively simple nature, his confidence in his fellows, and his lack of humor combined to prevent his concealing what many feel but are better able to hide. From the time he entered public life till he died he was a strong force constantly working for righteousness….To Sumner more than to any single man, except possibly Lincoln, the colored race owes its emancipation and such measure of equal rights as it now enjoys.[98]

Sumner's biographer David Donald, a Southerner, presents Sumner in his Pulitzer Prize-winning first volume, Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War (1960), as an insufferably arrogant moralist; an egoist bloated with pride; pontifical and Olympian, and unable to distinguish between large issues and small ones. Donald concludes that Sumner was a coward who avoided confrontations with his many enemies, whom he routinely insulted in prepared speeches.[99] But in Donald's second volume, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (1970), he was much more favorable to Sumner, and though critical, recognized his large contribution to the positive accomplishments of Reconstruction.[100]

Donald notes Sumner's troubles in dealing with his colleagues:[101]

Distrusted by friends and allies, and reciprocating their distrust, a man of "ostentatious culture", "unvarnished egotism", and "'a specimen of prolonged and morbid juvenility,'" Sumner combined a passionate conviction in his own moral purity with a command of 19th-century "rhetorical flourishes" and a "remarkable talent for rationalization". Stumbling "into politics largely by accident", elevated to the United States Senate largely by chance, willing to indulge in "Jacksonian demagoguery" for the sake of political expediency, Sumner became a bitter and potent agitator of sectional conflict. Carving out a reputation as the South's most hated foe and the Negro's bravest friend, he inflamed sectional differences, advanced his personal fortunes, and helped bring about national tragedy.

Lawyer David O. Stewart said of him:[102]

Much about Sumner was in the abstract. For all his oratorical prowess, he was not an effective legislator.

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote of Sumner:

Mr. Sumner's position is exceptional in its honor…. In Congress, he did not rush into party position. He sat long silent and studious. His friends, I remember, were told that they would find Sumner a man of the world like the rest; "it is quite impossible to be at Washington and not bend; he will bend as the rest have done." Well, he did not bend. He took his position and kept it…. I think I may borrow the language which Bishop Burnet applied to Sir Isaac Newton, and say that Charles Sumner "has the whitest soul I ever knew."… Let him hear that every man of worth in New England loves his virtues.[103]

In popular culture

In the 2012 film Lincoln, Sumner is portrayed by actor John Hutton.[104]

In the 2013 film Saving Lincoln, Sumner was portrayed by Creed Bratton.[105]

Personal life

Sumner was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1843.[106] He served on the society's board of councilors from 1852 to 1853, and later in life served as the society's secretary of foreign correspondence from 1867 to 1874.[107]

Marriage

Sumner was a bachelor for most of his life. In 1866, he began courting Alice Mason Hooper, the widowed daughter-in-law of Massachusetts Representative Samuel Hooper, and they married that October. Their marriage was unhappy. Sumner could not respond to his wife's humor, and Alice had a ferocious temper. That winter, Alice began going out to public events with Prussian diplomat Friedrich von Holstein. This caused gossip in Washington, but Alice refused to stop seeing Holstein. When Holstein was recalled to Prussia in the spring of 1867, Alice accused Sumner of engineering the action, which Sumner denied. They separated the following September.[108] Sumner's enemies used the affair to attack Sumner's manhood, calling him "The Great Impotency." The situation depressed and embarrassed Sumner.[109] He obtained an uncontested divorce on the grounds of desertion on May 10, 1873.[110]

Memorials

_-_Anne_Whitney_sculptor.JPG.webp)

The following are named after Charles Sumner:

- Sumner Street in Newton Centre, Massachusetts

- Charles Sumner Elementary School, Camden, New Jersey

- Charles Sumner – Junior High School 65 in New York City;

- Charles Sumner Elementary School in Roslindale, Massachusetts

- Sumner Avenue in Springfield, Massachusetts

- Charles Sumner School and museum in Washington, D.C.

- Sumner Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas, now closed, a school that played a key role in the landmark 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education and is on the National Register of Historic Places[111][112]

- Charles Sumner Math & Science Community Academy Elementary School in Chicago, Illinois

- Sumner Academy of Arts & Science in Kansas City, Kansas

- Charles Sumner House, Sumner's home in Boston

- Sumner Library in Minneapolis[113]

- Sumner County, Kansas[114]

- Sumner, Iowa

- Sumner, Nebraska

- Sumner, Washington[115]

- Sumner, Oregon

- Avenida Charles Sumner, Distrito Nacional, Dominican Republic

- Avenue Charles Sumner, Port-au-Prince, Haiti

- Sumner Avenue, Eastvale, California

- Sumner Avenue, Schenectady, New York

- SS Charles Sumner, a World War II Liberty cargo ship.

- Sumner Street in Salem, Massachusetts

- Sumner was sculpted by Edmonia Lewis

- In Barnum's American Museum, there were wax statues of Brooks attacking Sumner (on the floor).

- Sumner School, West Virginia

- Sumner Hill and Sumner Hill Road in Stamford, VT

See also

Notes

- Taylor 2001, p. 266.

- "Charles Sumner." Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2009. available online

- Donald 1960, p. 3.

- Donald 1960, p. 4.

- Donald 1960, pp. 6–7.

- Donald 1960, p. 130.

- Donald 1960, p. 104.

- Donald 1960, p. 105.

- Donald 1960, p. 14.

- George Henry Haynes, Charles Sumner (G.W. Jacobs & Company, 1909), pg. 21

- Chisholm 1911, p. 81.

- McCullough 2011, pp. 21–24.

- McCullough 2011, pp. 30, 42, 47.

- McCullough 2011, pp. 59, 130.

- McCullough 2011, p. 131.

- C-SPAN 2 McCullough 2011 National Book Festival

- Langguth, A. J. (2014). After Lincoln: How the North Won the Civil War and Lost the Peace. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-4516-1732-0.

- Hyser, Raymond M.; Arndt, J. Chris (2011). Voices of the American Past: Documents in U.S. History. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-111-34124-4.

- Donald 1960, p. 65-71.

- Harpers' Encyclopædia of United States from 458 A.D. to 1905. Vol. 8. New York: Harper & Brothers. 1905. pp. 458–459.

- Donald 1960, p. 174.

- Walther, Eric H. (2004). The Shattering of the Union: America in the 1850s. Lanham, MD: SR Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8420-2799-1.

- Donald 1960, p. 152.

- Donald 1960, pp. 180.

- Myers, John L. (2005). Henry Wilson and the coming of the Civil War. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-2608-4. OCLC 52559145.

- Two short-term appointees held Webster's seat from July 1850 to March 1851, when Sumner's full term began. Stephen Puleo, A City So Grand: The Rise of an American Metropolis, Boston 1850–1900, 29

- Charles Sumner, Freedom National; Slavery Sectional: Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner… (Boston: Ticknor, Reed and Fields, 1852), available online, accessed June 24, 2011

- Chisholm 1911, p. 82.

- Donald 1960, p. 236.

- Sumner, Charles (1856). The Crime Against Kansas. John P. Jewett & Company. p. Title page.

- Long, William R. (August 8, 2005). "Charles Sumner (1811–74) – Three Essays on A Massachusetts Abolitionist". www.drbilllong.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- Pfau 2003, p. 393.

- "14.2 The Coming of the Civil War." America: History of Our Nation, by James West. Davidson, Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009, pp. 186–94.

- The relationship between Brooks and Butler is often reported inaccurately. "In reality, Brooks's father Whitfield Brooks, and Andrew Butler were first cousins." Mathis, Robert Neil (October 1978). "Preston Smith Brooks: The Man and His Image". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 79 (4): 296–310. JSTOR 27567525.

- Puleo 2012, p. 112.

- Donald 1960, p. 293.

- Puleo, 36–37

- Puleo, 102, 114–15

- William E. Gienapp, "The Crime Against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party", Civil War History, 25 25 (1979): 218–45

- Thomas G. Mitchell, Anti-slavery politics in antebellum and Civil War America (2007) p. 95

- McCullough 2011, pp. 225–31.

- Sumner's chair was later purchased by Bates College, an abolitionist-leaning school with which Sumner was involved. Faith by their Works: The Progressive Tradition at Bates College from 1855 to 1877 Archived September 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- McCullough 2011, p. 233.

- Puleo 2012, pp. 113–20.

- Oates (December 1980), The Slaves Freed, American Heritage Magazine

- Stanley Coben, "Northeastern Business and Radical Reconstruction: A Re-examination", Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 46, No. 1 (Jun. 1959), pp. 67–90 in JSTOR

- Gilbert Osofsky, "Cardboard Yankee: How Not to Study the Mind of Charles Sumner", Reviews in American History Vol. 1, No. 4 (Dec. 1973), pp. 595–606 in JSTOR quotes are in Osofsky's words on pp. 595, 596

- Donald 1960, p. 319.

- Haynes 1909, pp. 247–51.

- Alfred N. Hunt, Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean (Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 187

- Haynes (1909), Charles Sumner, pp. 251–58

- David Donald, Jean Harvey Baker, and Michael F. Holt, The Civil War and Reconstruction (2001), 135–38

- Foner (1983), The New View Of Reconstruction, American Heritage Magazine

- Goldstone, p. 18

- Donald, 2: 532

- Donald 1970, p. 532.

- Donald 1970, p. 587.

- Daniels, Roger (2004). Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 13–16. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- John Mercer Langston, Representative, 1890–1891, Republican from Virginia, Black Americans in Congress series, archived from the original on July 2, 2012, retrieved November 12, 2012

- Richard Gerber, and Alan Friedlander, The Civil Rights Act of 1875 A Reexamination (2008)

- Donald 1970, p. 337.

- Reynolds, Robert L. (December 1960). "Seward's Wise Folly". American Heritage. 12 (1). Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- Fixico, Donald Lee (2008). Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-57607-880-8. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- "Treaty with Russia". Library of Congress. March 30, 1867. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- Sumner (April 9, 1867), p. 48.

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- Gallien, Max; Weigand, Florian (December 21, 2021). The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling. Taylor & Francis. p. 32 2021. ISBN 9-7810-0050-8772.

- David Keys (June 24, 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- Corning, Amos Elwood (1918). Hamilton Fish. Lamere Pub. Co. pp. 59–84.

- McFeely (1981), p. 337

- McFeely (1981), pp. 332, 333

- McFeely (1981), pp. 338, 339.

- Storey 1900, pp. 379–81.

- Smith (2001), p. 501, 502

- Storey 1900, pp. 382–84.

- Smith (2001), p. 504

- Storey 1900, pp. 384–86.

- Sumner (March 21, 1871), Violations of International Law and Usurpations of War Powers, p. 3

- Smith (2001), Grant, pp. 503–04

- Storey 1900, pp. 392, 394.

- Donald 1970, pp. 446–47.

- Andrew L. Slap, The doom of Reconstruction: the liberal Republicans in the Civil War era pp. xiii, 225

- "Obituary. Joshua B. Smith". Boston Post. July 7, 1879. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- Haynes 1909, p. 431.

- Bradford, pp. 43, 45

- Bradford, pp. 47–48, 52–53, 54

- Bradford, pp. 71–72

- Bradford, p. 72

- Bradford, p. 94

- "Lying in State or in Honor". US Architect of the Capitol (AOC). Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Puleo, 186–89

- Kennedy, John (1956). Profiles in Courage. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-095544-1.

- Ruchames (1953)

- W. A. Dunning, Reconstruction, Political and Economic (1907); Howard K. Beale, The Critical Year (1930) was revisionist.

- Kagan, Robert Dangerous Nation, p. 278

- Wendell Phillips letter, 'Boston Daily Advertiser,' March 11, 1873.

- David Donald, "Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man," 587

- Storey (1900), pp. 427–28

- Osofsky, Cardboard Yankee, pp. 597–98

- Grimes, William (May 19, 2009). "David Herbert Donald, Writer on Lincoln, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- Goodman's paraphrase of Donald in Goodman (1964) p. 374

- Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: the Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. New York: Simon and Schuster p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4165-4749-5.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "The Assault on Mr. Sumner". In: The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, in 12 vols. Centenary Edition. Vol. 11. Miscellanies. Houghton Mifflin, 1904. pp. 245–52.

- McDonough, Jodi (November 17, 2012). "Lincoln-A History Lesson For Today". In Good Taste Denver.

- Brian Gallagher (February 15, 2013). "Creed Bratton Talks History, The Office and Saving Lincoln". MovieWeb.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- Dunbar, B. (1987). Members and Officers of the American Antiquarian Society. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

- Donald, 2:293

- Donald, 2:571

- New York Times: Hon. Charles Sumner Obtains a Decree of Divorce, May 11, 1873, accessed June 22, 2011

- "CJOnline.com – Q&A: Sumner school named after anti-slavery leader". Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- National Register of Historical Places – Kansas (KS), Shawnee County

- Sumner Library

- "Sumner County Website". Archived from the original on February 11, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

- Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington geographic names. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 296.

Books

- Donald, David Herbert (1960). Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War.

- Goodman, Paul (September 1964). "David Donald's Charles Sumner Reconsidered". The New England Quarterly. 37 (3): 373–387. doi:10.2307/364037. JSTOR 364037.

- Osofsky, Gilbert (December 1973). "Cardboard Yankee: How Not to Study the Mind of Charles Sumner". Reviews in American History. 1 (4): 595–606. doi:10.2307/2701730. JSTOR 2701730.

- Donald, David Herbert (1970). Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man.

- Foner, Eric (1970). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War.

- Foreman, Amanda (2011). A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War. New York: Penguin Random House.

- Haynes, George Henry (1909). Charles Sumner. ISBN 9780722284407.

- Hoffer, Williamjames Hull (2010). The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- McCullough, David (2011). The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris.

- Puleo, Stephen (2012). The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-59416-516-0.

- Storey, Moorfield (1900). Charles Sumner. Boston, New York, Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- Taylor, Anne-Marie (2001). Young Charles Sumner and the Legacy of the American Enlightenment, 1811–1851. U. of Massachusetts Press. p. 422.

Articles

- Cohen, Victor H. (May 1956). "Charles Sumner and the Trent Affair". The Journal of Southern History. 22 (2): 205–219. doi:10.2307/2954239. JSTOR 2954239.

- Foner, Eric (October–November 1983). "The New View Of Reconstruction". American Heritage Magazine. 34 (6).

- Frasure, Carl M (April 1928). "Charles Sumner and the Rights of the Negro". The Journal of Negro History. 13 (2): 126–149. doi:10.2307/2713959. JSTOR 2713959. S2CID 149885691.

- Gienapp, William E. (September 1979). "The Crime against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party". Civil War History. 25 (3): 218–45. doi:10.1353/cwh.1979.0005. S2CID 145527756.

- Hidalgo, Dennis (1997). "Charles Sumner and the Annexation of the Dominican Republic". Itinerario. XXI (2): 51–66. doi:10.1017/S0165115300022841. S2CID 163872610.

- Jager, Ronald B. (September 1969). "Charles Sumner, the Constitution, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875". The New England Quarterly. 42 (3): 350–372. doi:10.2307/363614. JSTOR 363614.

- Nason, Elias (1874). The Life and Times of Charles Sumner: His Boyhood, Education and Public Career. Boston: B. B. Russell.

- Oates, Stephen B. (December 1980). "The Slaves Freed". American Heritage Magazine. Vol. 32, no. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- Pfau, Michael William (2003). "Time, Tropes, And Textuality: Reading Republicanism In Charles Sumner's 'Crime Against Kansas'". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 6 (3): 385–413. doi:10.1353/rap.2003.0070. S2CID 144786197.

- Pierson, Michael D. (December 1995). "'All Southern Society Is Assailed by the Foulest Charges': Charles Sumner's 'The Crime against Kansas' and the Escalation of Republican Anti-Slavery Rhetoric". The New England Quarterly. 68 (4): 531–557. doi:10.2307/365874. JSTOR 365874.

- Ruchames, Louis (April 1953). "Charles Sumner and American Historiography". Journal of Negro History. 38 (2): 139–160. doi:10.2307/2715536. JSTOR 2715536. S2CID 150278539.

- Sinha, Manisha (2003). "The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War". Journal of the Early Republic. 23 (2): 233–262. doi:10.2307/3125037. JSTOR 3125037.

- Williams, T. Harry (December 1954). "Investigation: 1862". American Heritage Magazine. 6 (1). Retrieved September 27, 2011.

Primary sources

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sumner, Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–82.

- Palmer, Beverly Wilson, ed. The Selected Letters of Charles Sumner 2 vols. (1990)

- Pierce, Edward L. Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner 4 vols., 1877–93. online edition

- Sumner, Charles. The Works of Charles Sumner online edition

- Sumner, Charles (April 9, 1867). Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, on the cession of Russian America to the United States (Speech). Making of America. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

External links

- United States Congress. "Charles Sumner (id: S001068)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Charles Sumner

- Sumner's "Crime Against Kansas" speech

- Works by Charles Sumner at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Charles Sumner at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Charles Sumner at Internet Archive

- The Liberator Files, Items concerning Charles Sumner from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

Works related to Charles Sumner at Wikisource

Works related to Charles Sumner at Wikisource Media related to Charles Sumner at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Sumner at Wikimedia Commons