Separation of Light from Darkness

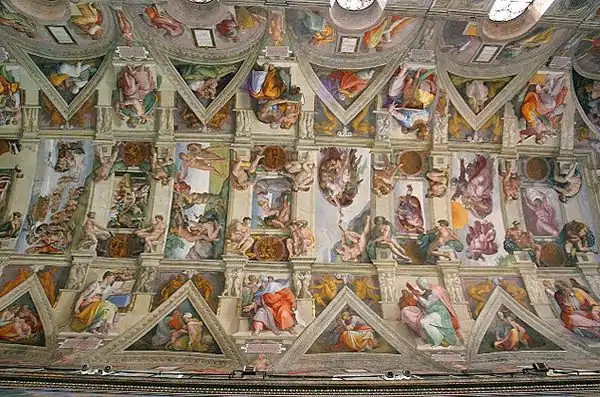

The Separation of Light from Darkness is, from the perspective of the Genesis chronology, the first of nine central panels that run along the center of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and which depict scenes from the Book of Genesis. Michelangelo probably completed this panel in the summer of 1512, the last year of the Sistine ceiling project. It is one of five smaller scenes that alternate with four larger scenes that run along the center of the Sistine ceiling. The Separation of Light from Darkness is based on verses 3–5 from the first chapter of the Book of Genesis:

- 3And God said, "Let there be light," and there was light.

- 4God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness.

- 5God called the light "day," and the darkness he called "night." And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.

| Separation of Light from Darkness | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Separazione della luce dalle tenebre | |

| |

| Artist | Michelangelo Buonarroti |

| Year | First half of 1512 |

| Type | Fresco |

| Location | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City |

Although in terms of the Genesis chronology it is the first of nine central panels along the Sistine ceiling, the Separation of Light from Darkness was the last of the nine panels painted by Michelangelo. Michelangelo painted the Sistine ceiling in two stages. Between May 1508 and the summer of 1511, he completed the "entrance half" of the Sistine chapel and ended this stage by painting the Creation of Eve and the scenes flanking this central panel. After an idle period of about 6 months, he painted the "altar half," starting with the Creation of Adam, between the winter of 1511 and October 1512.

Composition

In the Separation of Light from Darkness, the image of God is framed by four ignudi and by two shields or medallions. The ignudi are young, nude males that Michelangelo painted as supporting figures at each corner of the five smaller narrative scenes along the center of the ceiling. There are a total of 20 ignudi. These figures are all different and appear less constrained within their space than the Ancestors of Christ or the Bronze Nudes. In the earliest frescoes painted by Michelangelo toward the entrance of the Sistine chapel, the ignudi are paired, and their poses are similar but with minor variations. The variations in the poses increase with each set until the poses of the final set of four ignudi in the Separation of Light from Darkness bear no relation to each other.

Although the meaning of these figures has never been completely clear, the Sistine scholar Heinrich Pfeiffer has proposed that the four ignudi associated with the Separation of Light from Darkness represent day and night, which echo the theme of light and darkness.[1] For instance, he points out that the ignudo next to God's right hand (on the side of darkness) is stretching as if awakening from sleep in the morning, that the diagonally opposed ignudo below God's knee (on the side of light) is carrying a heavy bundle of oak garlands on his shoulders, representing a daytime activity, and that the ignudo next to God's left arm is falling asleep and signifies nighttime. Pfeiffer and other scholars have also suggested that in Michelangelo's Sistine iconography the ignudi represent angels and that the Bronze Nudes below the ignudi are fallen angels.

Two shields or medallions accompany each set of four ignudi in the five smaller Genesis panels along the center of the Sistine ceiling. They are often described as painted to resemble bronze. Each is decorated with a picture from either the Old Testament or the Book of Maccabees from the Apocrypha. The subjects of the shields are often violent. In the Separation of Light from Darkness the shield above God shows Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac (Genesis 22:9–12), and the one below God shows the prophet Elijah as he is carried up to heaven in a chariot of fire (2 Kings 2:11).

At the center of the composition, God is shown in contrapposto rising into the sky, with arms outstretched separating the light from the darkness. Michelangelo employed in this fresco the challenging ceiling fresco technique of sotto in su ("from below, upward"), which makes a figure appear as if it is rising above the viewer by using foreshortening. The contrapposto pose was also used by Michelangelo in his David (1501-1504). It is reported that Michelangelo painted this fresco in a single giornata, that is, a single working day of approximately eight hours.[2] During Michelangelo's lifetime, this fresco was considered evidence of the painter's technical prowess at its peak. For instance, Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), Michelangelo's student and biographer, wrote in 1550:

"Furthermore, to demonstrate the perfection of his art and the greatness of God, Michelangelo depicted God dividing the light from darkness in these scenes, where He is seen in all His majesty as He sustains himself alone with open arms with the demonstration of love and creative energy.[3]

According to Vasari, Michaelangelo has “lifted the veil” of darkness typically found in artwork of the Renaissance, employing the skill of chiaroscuro, by combining the intense lights and extreme darks in this symbolic artwork.[4]

Art historians have noted several unusual features of this fresco. Andrew Graham-Dixon has pointed out that God has exaggerated pectoral muscles suggestive of female breasts, which he interprets as Michelangelo's attempt to illustrate "male strength but also the fecundity of the female principle."[5] In addition it has been noted that the anatomy of God's neck is too complex and does not resemble the normal contour of the neck. The lighting scheme of the image has been noted to be inconsistent; whereas the entire scene is illuminated from the bottom left, God's neck appears to have a different light source from the right.

Anatomical interpretations

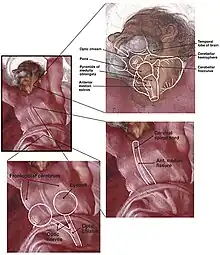

Several authors have proposed that Michelangelo concealed anatomical images in this fresco and that these anatomical images account for its unusual features. In an article published in the journal Neurosurgery in May 2010, Ian Suk, a medical illustrator, and Rafael Tamargo, a neurosurgeon, both from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, suggested that Michelangelo concealed three neuroanatomical images in the Separation of Light from Darkness.[6][7] Suk and Tamargo explained that Michelangelo started to dissect cadavers at the age of 17–19 years and continued his anatomical studies throughout his life. As a result of his dissections, Michelangelo probably developed a detailed understanding of gross anatomy of the brain and spinal cord. They showed that the anatomical details in God's neck are unlike those of either other necks painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel or of other necks painted by Michelangelo's contemporaries, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael). The unusual anatomy of God's neck is particularly evident when it is contrasted with the anatomy of the neck of the ignudo facing God in the upper left corner of the panel. The position of the neck of this ignudo is almost identical to that of God's neck, yet the ignudo's neck does not have any of the unusual lines found in God's neck. It is possible that Michelangelo placed these two analogous neck perspectives side by side to emphasize and contrast the hidden image in God's neck.

Suk and Tamargo suggested that Michelangelo concealed a sophisticated image of the undersurface of the brainstem in God's neck and that by following Michelangelo's lines in God's neck, one can outline an anatomically correct image of the brainstem, cerebellum, temporal lobes, and optic chiasm. In addition, they suggested that Michelangelo also included an anterior view of the spinal cord in God's chest and an image of the optic nerves and globes in God's abdomen. They showed how a "shadow analysis" of the unusual lines in God's neck correspond to specific spaces around the brainstem known as the "arachnoid cisterns," which were described in detail much later in 1875 but which Michelangelo inadvertently depicted in God's neck since he was able to render images with almost photographic accuracy. They concluded that "being a painter of genius, a master anatomist, and a deeply religious man, Michelangelo cleverly enhanced his depiction of God in the iconographically critical panels on the Sistine Chapel vault with concealed images of the brain and in this way celebrated not only the glory of God, but also that of His most magnificent creation."

Of note is that in an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in October 1990, Frank Meshberger, an obstetrician-gynecologist from Indiana, explained that Michelangelo similarly concealed an image of the brain in the shroud surrounding God in the Creation of Adam.[8][7] Since Michelangelo painted the Creation of Adam and the Separation of Light from Darkness, along with two other Genesis panels, as a single thematic unit between the winter of 1511 and October 1512, it is possible that these four central panels have an underlying anatomical motif. Indeed, Garabed Eknoyan, a nephrologist from Baylor College of Medicine, proposed in an article published in Kidney International in March 2000 that Michelangelo concealed an image of a kidney in the Separation of Land and Water, the third panel in the Genesis series.[9] Michelangelo was particularly interested in kidney function because he suffered from kidney stones throughout his adult life and documented this interest in his letters and poems, according to Eknoyan.

Alternatively, the concealed anatomical image in God's neck in the Separation of Light from Darkness has been interpreted as a goiter (an enlarged thyroid gland). In an article published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in December 2003, Lennart Bondeson and Anne-Greath Bondeson from Malmo University Hospital in Sweden, argued that the abnormality in God's neck is a goiter.[10] This interpretation has been challenged on the basis that goiters typically occur lower in the neck and, as stated by Suk and Tamargo, that "it is unlikely that Michelangelo, a deeply religious individual, would have defiled the image of God in this important panel by giving God a goiter."

Along these lines, Gilson Barreto and Marcelo G. de Oliveira, in a book published in 2004,[11] analyzed the Separation of Light from Darkness and noted that God's upper chest and outstretched arms define a "U" shape, which they suggested is reminiscent of the hyoid bone, although they do not offer a thematic explanation for this structure in the fresco.

References

- Pfeiffer, Heinrich W. The Sistine Chapel: A New Vision. New York/London, Abbeville Press Publishers, 2007

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew. Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel. London, England: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 2008

- Vasari, Giorgio. The Lives of the Artists. 1550.

- Barolsky, Paul (2003). "The Divine Origins of Chiaroscuro". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 22 (4): 8–9. JSTOR 23206787 – via JSTOR.

- Graham-Dixon 2008

- Suk, Ian; Tamargo, Rafael J. (May 2010). "Concealed Neuroanatomy in Michelangelo's Separation of Light From Darkness in the Sistine Chapel (abstract)". Neurosurgery. 66 (5): 851–861. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000368101.34523.E1. PMID 20404688.

- Fields, R. Douglas (27 May 2010). "Michelangelo's secret message in the Sistine Chapel: A juxtaposition of God and the human brain". Scientific American. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Meshberger, Frank Lynn (10 October 1990). "An Interpretation of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam Based on Neuroanatomy". JAMA. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association. 264 (14): 1837–41. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03450140059034. PMID 2205727. Pdf. Excerpt on Mental Health & Illness.com. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- Eknoyan, Garabed (March 2000). "Michelangelo: Art, anatomy, and the kidney". Kidney International. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 57 (1): 1190–1201. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00947.x. PMID 10720972. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Bondeson, L., and Bondeson, A. G.. Michelangelo's divine goitre. J. R. Soc. Med. 96: 609–611, December 2003

- Barreto, G., and de Oliveira, M. G.. A Arte Secreta de Michelangelo. Uma Licao de Anatomia na Capela Sistina. Editoria Arx, Sao Paulo, Brasil, 2004