September (Roman month)

September (from Latin septem, "seven") or mensis September was originally the seventh of ten months on the ancient Roman calendar that began with March (mensis Martius, "Mars' month"). It had 29 days. After the reforms that resulted in a 12-month year, September became the ninth month, but retained its name. September followed what was originally Sextilis, the "sixth" month, renamed Augustus in honor of the first Roman emperor, and preceded October, the "eighth" month that like September retained its numerical name contrary to its position on the calendar. A day was added to September in the mid-40s BC as part of the Julian calendar reform.

September has none of the archaic festivals that are marked in large letters for other months on extant Roman fasti. Instead, about half the month is devoted to the Ludi Romani, "Roman Games", which developed as votive games for Jupiter Optimus Maximus ("Jupiter Best and Greatest"). The Ludi Romani are the oldest games instituted by the Romans, dating from 509 BC. On the Ides of September (the 13th), Jupiter was honored with a public banquet, the Epulum Jovis.[2] A nail-driving ritual in the temple marked the passing of the political year during the Republican era, and in the earliest period, the consuls took office on the Ides of September.[3] The month was often represented in art by the grape harvest.

September was the birth month of no fewer than four major Roman emperors, including Augustus. The emperor Commodus renamed the month after either himself or Hercules—an innovation that was repealed after his murder in 192. In the Eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, the year began with September on some calendars, and was the beginning of the imperial tax year.

In the agricultural year

For the month of September, ancient farmers' almanacs (menologia rustica) take note of the autumnal equinox on September 24, and the equal number of daylight and nocturnal hours. They note that the month began with the sun in the astrological sign of Virgo, and was under the guardianship (tutela) of Volcanus (the god Vulcan). On an unspecified date an Epulum Minervae (Banquet of Minerva) is to be held, probably as part of the general epulum on the Ides.[4]

The farmer is instructed to coat wine vessels with pitch, pick apples, and loosen the compacted soil around trees.[5] In his agricultural treatise, Varro assigns farmers additional tasks in the period from the rising of Sirius to the equinox. Straw must be cut, haystacks pitched, arable land ploughed, fodder gathered, and well-watered meadows mown a second time.[6] Columella specifies that sloping ground should be ploughed between the Kalends (1st)and the Ides (13th).[7]

Equinox and medical theory

The Aëtius parapegma is an almanac that appears as a chapter in the 6th-century Tetrabiblos of Aëtius of Amida. It treats the rising and setting of constellations, weather forecasting, and medical advice as closely intertwined, and notes of the equinox (placed on September 25) that

There is the greatest disturbance in the air for three days previous. Thus it is necessary to be careful neither to phlebotomize, nor purge, nor otherwise to change the body violently from the 15th of September through the 24th.

The passage is presented as advice for physicians, based on the principle that "the bodies of healthy people, and especially those of sick people, change with the condition of the air".[8]

Iconography of the month

The vintage, with bunches or baskets of grapes, predominates in both verbal and visual allegories of September, particularly in mosaics depicting the months.[9] In the manuscripts that preserve the Calendar of Filocalus (354 AD), September is represented by a nude male wearing only a long light scarf over one shoulder. The conventional bunch of grapes appears under his left hand, outstretched to hold a basket, on the top of which are arrayed five puzzling picks or skewers. Over his right shoulder is placed a basket holding two pyramids of six figs or small flasks.[10] A vessel, presumably to receive the new wine, is sunk into the ground on either side of him. Over the one to his right, he dangles a lizard on a string, a motif that recurs in imagery associated with Dionysus, the god of wine. The exact significance of the lizard is uncertain. It may represent a magico-medical charm to ensure healthy wine, with the lizard either a potent lustration or the potential damage to be warded off. The lizard is also an attribute of Apollo Sauroctonos.[11]

In calendar mosaics from Hellín in Roman Spain and Trier in Gallia Belgica, September is represented by the god Vulcan, the tutelary deity of the month in the menologia rustica, depicted as an old man holding tongs.[12] The mosaic from Hellín (2nd–3rd century) depicts each of the months as a personification with or representing a zodiac sign. September is shown holding balance scales and assisted by Vulcan. The scales represent Libra, the astrological sign entered late in the month.[13] In the Laus omnium mensium ("Praise of All the Months"), a poem dating to the early 6th century, September "divides the hours equally for Libra".[14]

In an ancient Christian mosaic from Gerasa in the province of Arabia (present-day Jordan), September has the typical attributes of a vintager in Roman art—a young man wearing a tunic and chlamys carries a bunch of grapes in his right hand and has a basket on his shoulder—but is labeled as Gorpiaios, the first month of the year in the local calendar, equivalent to the period August 19 to September 17.[15]

Dates

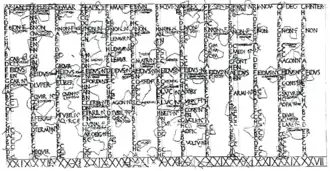

The Romans did not number days of a month sequentially from the first day through the last. Instead, they counted back from the three fixed points of the month: the Nones (5th or 7th, depending on the month), the Ides (13th or 15th), and the Kalends (1st) of the following month. The Nones of September was the 5th, and the Ides the 13th. The last day of September was the pridie Kalendas Octobrīs,[16] "day before the Kalends of October". Roman counting was inclusive; September 9 was ante diem V Idūs Septembrīs, "the 5th day before the Ides of September," usually abbreviated a.d. V Id. Sept. (or with the a.d. omitted altogether); September 23 was IX Kal. Oct., "the 9th day before the Kalends of October," on the Julian calendar (VIII Kal. Oct. on the pre-Julian calendar, when September had only 29 days).

On the calendar of the Roman Republic and early Principate, each day was marked with a letter to denote its religiously lawful status. In September, these were:

- F for dies fasti, days when it was legal to initiate action in the courts of civil law;

- C for dies comitalis, a day on which the Roman people could hold assemblies (comitia), elections, and certain kinds of judicial proceedings;

- N for dies nefasti, when these political activities and the administration of justice were prohibited;

- NP, the meaning of which remains elusive, but which marked feriae, public holidays.

By the late 2nd century AD, extant calendars no longer show days marked with these letters, probably in part as a result of calendar reforms undertaken by Marcus Aurelius.[17] Days were also marked with nundinal letters in cycles of A B C D E F G H, to mark the "market week"[18] (these are omitted in the table below).

On a dies religiosus, one of which occurred on September 14, individuals were not to undertake any new activity, nor do anything other than tend to the most basic necessities. A dies natalis was an anniversary such as a temple founding or rededication, sometimes thought of as the "birthday" of a deity. During the Imperial period, some of the traditional festivals localized at Rome became less important, and the birthdays and anniversaries of the emperor and his family gained prominence as Roman holidays. A dies imperii marked the date of an emperor's accession. Only sacrifices and observances pertaining to Imperial cult are preserved for September on the calendar of military religious observances known as the Feriale Duranum, in part because of its fragmentary condition. After the mid-1st century AD, a number of dates are added to calendars for spectacles and games (ludi) in the venue called a "circus". These ludi circenses were held in honor of various deities, but during September mainly for imperial holidays.[19]

Unless otherwise noted, the dating and observances on the following table are from H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 96–115. After the Ides, dates are given for the 30-day month of the Julian calendar; pre-Julian dates of festivals are noted parenthetically.

| Modern date | Roman date | status | Observances |

|---|---|---|---|

| September 1 | Kalendae Septembrīs | F | • dies natalis for the Temple of Juno Regina ("Juno the Queen"), from 392 BC • dies natalis for the temples of Jupiter the Thunderer on the Capitoline and Jove the Free, from early in the reign of Augustus |

| 2 | a.d. IV Non. Sept.[20] | F | |

| 3 | III Non. Sept.[21] | C | |

| 4 | pridie Nonas Septembrīs (abbrev. prid. Non. Sept.) | C | |

| 5 | Nonae Septembrīs | F | • dies natalis of one of the two Temples of Jupiter Stator[22] • Ludi Romani begin • Mammes vindemia, a festival of the vintage for Dionysus (Roman Liber), after the mid-1st century AD[23] |

| 6 | VIII Id. Sept. | F | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 7 | VII Id. Sept. | C | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 8 | VI Id. Sept.[24] | C | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 9 | V Id. Sept. | C | • Ludi Romani continue • dies natalis of Aurelian, with circus games[25] |

| 10 | IV Id. Sept. | C | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 11 | III Id. Sept. | C | • Ludi Romani continue • dies natalis for a temple of Asclepius |

| 12 | pridie Idūs Septembrīs (abbrev. prid. Id. Sept.) | N | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 13 | Idūs Septembrīs | NP | • sacrifice of the Ides sheep (ovis idulis) for Jupiter Optimus Maximus • Epulum Jovis, banquet for Jove along with Juno and Minerva, the Capitoline Triad • clavis annalis, the ritual of the year-nail |

| 14 | XVIII Kal. Oct. | F dies religiosus | • Ludi Romani continue • probatio equorum ("review of the horses", pre-Julian XVII Kal. Oct.), an equestrian procession of knights • accession of Domitian |

| 15 | XVII Kal. Oct. | N | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 16 | XVI Kal. Oct.[26] | C | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 17 | XV Kal. Oct. | C | • Ludi Romani continue |

| 18 | XIV Kal. Oct. | N | • Ludi Romani continue • dies natalis of Trajan • dies imperii of Nerva[27] • beginning of the Ludi Triumphales for Constantine after 324 AD[28] |

| 19 | XIII Kal. Oct. | C | • Ludi Romani conclude • Ludi Triumphales continue • dies natalis of Antoninus Pius[29] |

| 20 | XII Kal. Oct. | C | • mercatus, market or fair days • Ludi Triumphales continue |

| 21 | XI Kal. Oct. | C | • mercatus continue • Ludi Triumphales continue |

| 22 | X Kal. Oct. | C | • mercatus continue * Ludi Triumphales conclude |

| 23 | IX Kal. Oct. | C | • dies natalis for the Temple of Apollo and Latona at the Theater of Marcellus (pre-Julian VIII Kal. Oct.) • dies natalis of Divus Augustus, with circus games[30] • mercatus conclude |

| 24 | VIII Kal. Oct. | C | |

| 25 | VII Kal. Oct. | C | |

| 26 | VI Kal. Oct. | C | • dies natalis for the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar (pre-Julian V Kal. Oct.) |

| 27 | V Kal. Oct. | C | • Profectio Divi ("The Setting Forth of the Divine"), with circus games, recorded in the Calendar of Filocalus (354 AD)[31] |

| 28 | IV Kal. Oct. | C | |

| 29 | III Kal. Oct. | C | • Ludi Fatales, games for the Fates, after the mid-1st century AD[32] |

| 30 | prid. Kal. Oct. | C | • Ludi Fatales |

Under the emperors

September has a concentration of imperial birthdays (dies natales): Aurelian on the 9th, Trajan on the 18th, Antoninus Pius on the 19th, and Augustus on the 23rd. Inscriptions throughout the Empire record religious dedications made on these days, often by military personnel. The Genius of Legio II Italica Pia, an Italian legion stationed in Noricum, received a dedication on September 18, 119 AD, the anniversary of Trajan's birth and Nerva's accession. This date may also have been the "birthday" of the unit (natalis aquilae).[33] At least two inscriptions record religious dedications on September 19, the birthday of Antoninus Pius. In the province of Germania Inferior, on this date in 190 AD, a camp prefect (praefectus castrorum) and his three sons dedicated an altar to Jupiter Optimus Maximus (IOM), Hercules, Silvanus, and the Genius of the "divine house" (domus divina, the imperial household).[34] In the same province, a prefect of Legio I Minerviae marked the renovation of a temple to Mars Militaris on September 19, 295, with a dedication to the wellbeing (salus) of the emperor.[35] Several inscriptions record dedications on the birthday of Augustus, including one in honor of the Eagle made in Roman Britain dually to the numen of Augustus and the Genius of Legio II Augusta (144 AD),[36] and an inscribed bronze Genius from Germania Superior donated to an association of standard bearers (246 AD).[37]

There were occasional attempts to rename September, emulating the successful renaming of the Roman months originally called Quinctilis (July, after Julius Caesar) and Sextilis (August, after Augustus). According to Suetonius, Tiberius declined the honor of having September named after himself, and October after his mother Livia.[38] Caligula insisted futilely that September be called Germanicus after his father.[39] Domitian (reigned 81–96 AD) also briefly renamed September, the month of his accession as emperor, mensis Germanicus after the triumph he celebrated over the Germanic Chatti.[40]

More sweepingly, in 184 AD Commodus renamed all the months of the year after names and aspects of himself. Cassius Dio lists Amazonius (January), Invictus, Felix, Pius, Lucius, Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Herculeus, Romanus, and Exsuperatorius. In this sequence, August as his birth month was renamed Commodus, and September was called by his title Augustus, with each of the months from May to September (Lucius to Augustus) represented by elements of his official nomenclature in their usual order.[41] The Historia Augusta also indicates that August was the month named Commodus, but is internally inconsistent:[42] at one point, Hercules, the patron deity chosen by Commodus, is said to have been the namesake for September,[43] while elsewhere October is the mensis Herculeus, as it is on Dio's list.[44] Several sources from late antiquity—among them Aurelius Victor, Eutropius, and Jerome—state that September was the mensis Commodus.[45] Dates recorded in the month of Commodus are exceedingly rare, with a graffito from Ostia Antica reading VII Kal. Commodas (July 26 or August 26, depending on whether Commodus was August or September); a date of III Nonas Commodias (August 3) in the Historia Augusta; and a fragmentary reference to the Idus Commodas ("Ides of Commodus") on a marble base at Lanuvium.[46] The innovation was repealed after his murder in 192.[47]

The new year in September

The Byzantine antiquarian Johannes Lydus, in his work on the months (De mensibus), says that the Romans had three new years: priestly, in January; national, in March; and a cyclical or political new year in September.[48] In Republican Rome, the senior magistrate[49] on the Ides of September drove a nail called the clavus annalis ("year-nail")[50] into the wall of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The ceremony occurred on the dies natalis of the temple, when the banquet for Jove was also held. The nail-driving ceremony, however, took place in a sacred space (templum) devoted to Minerva, on the right side of the shrine (aedes) of Jupiter. This ritual predated the common use of written letters, according to the Augustan historian Livy, and was within Minerva's sphere of influence because the concept of "number" was invented by her.[51]

In the Roman East, the birthday of Augustus on September 23 was the first day of the new year on some calendars, including possibly the calendar of Heliopolis (Baalbek in present-day Lebanon).[52] The tax year began in September, when the Praetorian Prefects published their budgets. The unfamiliarity of the Roman year in the Eastern provinces, and the difficulties of coordinating disparate calendars, made it convenient in some instances to date by means of the tax year.[53] In Roman Syria, for instance, the Seleucid year began October 1, but was adjusted to September 1 in the 5th century to coincide with the tax year.[54]

See also

- Vendémiaire, the "grape harvester" month, beginning on the autumnal equinox, on the French Republican Calendar

References

- Aïcha Ben Abed, Tunisian Mosaics: Treasures from Roman Africa (Getty Publications, 2006), p. 113.

- H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 182–183.

- J. Rufus Fears, "The Cult of Jupiter and Roman Imperial Ideology," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.17.1 (1981), p. 12.

- Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies, pp. 182–183.

- Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies, p. 182.

- Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies, p. 182.

- Columella, De re rustica 2.4.11; Daryn Lehoux, Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World: Parapegmata and Related Texts in Classical and Near-Eastern Societies (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 50–51.

- Lehoux, Astronomy, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World, pp. 184–185.

- Doro Levi, "The Allegories of the Months in Classical Art," Art Bulletin 23.4 (1941), p. 267.

- Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 1990), pp. 103–104.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 104–105; Levi, "The Allegories of the Months in Classical Art," pp. 267–268.

- Charlotte R. Long, "The Pompeii Calendar Medallions," American Journal of Archaeology 96.3 (1992), pp. 494–495.

- Rachel Hachlili, Ancient Mosaic Pavements: Themes, Issues, and Trends (Brill, 2009), p. 40.

- Levi, "The Allegories of the Months in Classical Art," p. 267.

- Hachlili, Ancient Mosaic Pavements, pp. 193, 232. The mosaic is from the Church of Elias, Mary and Soreg.

- The month name is construed as an adjective modifying the feminine plural Kalendae, Nonae or Idūs.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 17, 122.

- Jörg Rüpke, The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History, and the Fasti, translated by David M.B. Richardson (Blackwell, 2011, originally published 1995 in German), p. 6.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 118ff.

- Abbreviated form of ante diem IV Nonas Septembrīs.

- Abbreviated form of ante diem III Nonas Septembrīs.

- Rüpke, Jörg (15 April 2011). The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History, and the Fasti. Richardson, David M. B. (translator). John Wiley & Sons. p. 98. ISBN 978-0470655085. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, pp. 105, 125, 240.

- Abbreviated form of ante diem VI Idūs Septembris, with the ante diem omitted altogether from this point.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 134.

- Abbreviated form of ante diem XVII Kalendas Octobris/-es with the ante diem omitted altogether, as in the rest of the month following.

- Duncan Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," Syria 65 (1988), p. 359.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 134.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 134.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 134.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 135.

- Salzman, On Roman Time, p. 123, conjecturing about what fatales indicates.

- CIL 3.15208; Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," p. 359.

- CIL 13.8016; Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," p. 359.

- CIL 13.8019; Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," p. 359.

- RIB 327; Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," p. 359.

- Collegium Victoriensium signiferorum: CIL 13.7754; Fishwick, "Dated Inscriptions and the Feriale Duranum," p. 359.

- Suetonius, Tiberius 26; Rüpke, The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine, p. 133.

- Suetonius, Caligula 15.2; Rüpke, The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine, p. 133.

- Suetonius, Domitian 13; Robert Hannah, "The Emperor's Stars: The Conservatori Portrait of Commodus," American Journal of Archaeology 90.3 (1986), p. 342; Rüpke, The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine, p. 133.

- Cassius Dio 72.15.3; M.P. Speidel, "Commodus the God-Emperor and the Army," Journal of Roman Studies 83 (1993), p. 112; Hannah, "The Emperor's Stars", p. 342.

- Hannah, "The Emperor's Stars", p. 341, note 23.

- Scriptores Historiae Augustae VII, as cited by A.W. van Buren, "Graffiti at Ostia," Classical Review 37 (1923), p. 163 (Commodus 11.8 in the citation of Hannah, "The Emperor's Stars", p. 341, note 23).

- Historia Augusta, "Commodus" 11.13; Hannah, "The Emperor's Stars", p. 341, note 23.

- Van Buren, "Graffiti at Ostia," p. 163, with detailed citations of the primary texts. See also J.F. Mountford, "De Mensium Nominibus," Journal of Hellenic Studies 43 (1923), p. 114, in relation to the Liber glossarum.

- Van Buren, "Graffiti at Ostia," pp. 163–164. The Lanuvium inscription is CIL 14.2113 (= ILS 5193).

- John R. Clarke, "The Decor of the House of Jupiter and Ganymede at Ostia Antica," in Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula (University of Michigan Press, 1991, 1994), p. 92; John R. Clarke, The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration (University of California Press, 1991), p. 322.

- Michael Maas, John Lydus and the Roman Past (Routledge, 1992), p. 61.

- Praetor maximus, the chief magistrate with imperium; T. Corey Brennan, The Praetorship in the Roman Republic (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 21.

- Festus, 49 in the edition of Lindsay, says that "the year-nail was so called because it was fixed into the walls of the sacred aedes every year, so that the number of years could be reckoned by means of them". See also Nortia and clavum fingere.

- Livy, 7.3; Brennan, Praetorship, p. 21.

- Alan E. Samuel, Greek and Roman Chronology: Calendars and Years in Classical Antiquity (C.H. Beck, 1972), pp. 174–176.

- Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (Getty Publications, 2003), pp. 122–123.

- Butcher, Roman Syria, p. 122.